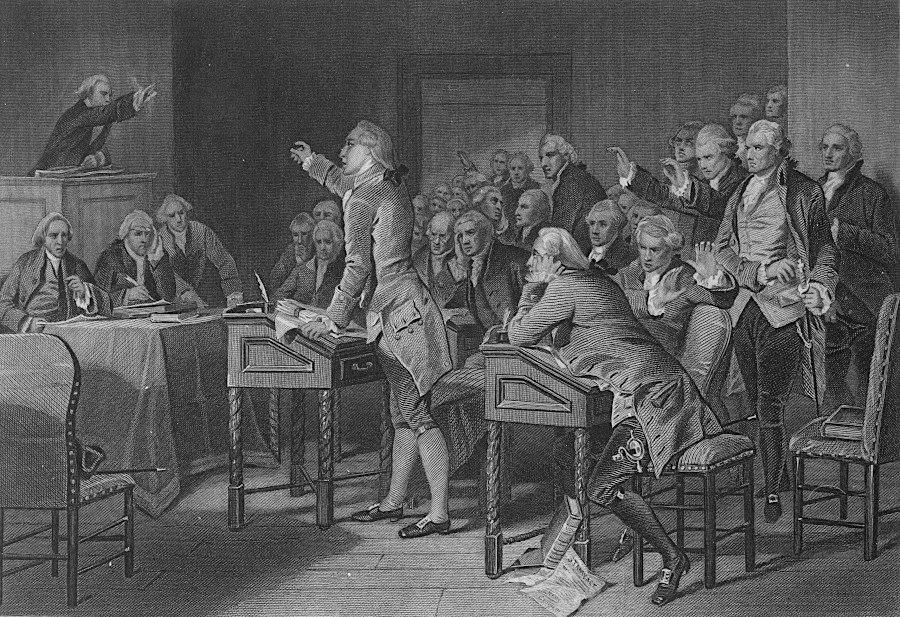

the House of Burgesses passed five of Patrick Henry's resolutions against the Stamp Act in 1765

Source: National Archives, Patrick Henry addressing the Virginia Assembly, 1765

the House of Burgesses passed five of Patrick Henry's resolutions against the Stamp Act in 1765

Source: National Archives, Patrick Henry addressing the Virginia Assembly, 1765

The great mystery of the Revolution is why rich Virginians supported revolution. After all, in 1775 the gentry were on top of the social and economic pyramid in Virginia. Revolutions displace the people on the top of the socio-economic ladder, the people with power. It would be logical for the poor, the marginalized, and the enslaved to want to overturn the system - but why would the gentry lead a revolution against themselves?

The politics of the Virginia gentry were shaped by the same forces that affected the Scottish businessmen and the frontier settlers. Those rich Virginians were very sensitive to the winds of change. The tobacco planters strove to maintain the appearance of independence, but they fell deeper and deeper into debt to British merchants.

George Washington often complained that he received shoddy goods and was charged excessively high prices, while his high-quality tobacco was not sold at the premium it deserved. Others were even more concerned, since they were risking bankruptcy if their English creditors refused to advance then any more funds in anticipation of a bigger/better crop.

The gentry felt it was essential to demonstrate they could vote as they pleased in the House of Burgesses. Similarly, the restrictions on voting rights in the colony were designed to ensure that the decisionmakers were voting for their own interests. Virginia's gentry wanted voters to make their own decisions, rather than take direction on how to vote because they were in debt to someone else.

Parliament had "corrupt boroughs" where someone could buy their way into Parliament, and that allowed the King to purchase extra votes to support his policies. The Virginians did not want the colonial governor - or other rivals in the legislature - to gain such extra influence.

The conflict ended up being triggered by new taxes. The gentry did not want to acknowledge that Parliament had the right to impose direct taxes on colonists. To control the power of officials in London and their appointees in Virginia, the gentry argued that all taxes on the colony had to be approved by the House of Burgesses.

In 1765, the natural ties of loyalty binding Virginia's gentry to England were stretched tight. George Mercer was one royal appointee who discovered that the theoretical dispute regarding taxation could become violent.

Mercer was a respected member of the Virginia gentry. He had served with George Washington at Fort Necessity and in the First Virginia Regiment, and had become the Lieutenant Colonel of the Second Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War. He was elected to the House of Burgesses in 1761, and was chosen by the Loyal Land Company to serve as their lobbyist in London in 1765.

He returned to Virginia in October, 1765 as the designated agent for collecting the stamp tax, which Parliament had imposed to help pay for the defense of the colonies. A mob of angry residents in Williamsburg threatened Mercer's life when he arrived. After he resigned (and quickly returned to England until his death in 1784...), no one in Virginia was willing to serve as the stamp tax collector and Parliament was forced to repeal the tax.

The French and Indian War, and then the Stamp Act crisis, first revealed the differences between Parliament and the colonies. The Virginians in particular had taxed themselves heavily to pay for defense during the French and Indian War. From London's perspective, however, England had borrowed heavily to pay for that war and the colonies still needed to pay their fair share of the continuing defense costs.

English regiments sent across the Atlantic had been the key to conquering Fort Duquesne (the French fort at the site of present-day Pittsburgh) and then conquering - and keeping - Canada. By eliminating the French from the continent, the English had substantially reduced the threat of the Native Americans on the frontier. The Iroquois, Shawnee, and Cherokee in particular no longer had the option of allying with the French and receiving gifts to spur attacks on the settlers or English forts on the frontier.

In addition, the English capture of Canada ensured that "foreign relations" with the Native Americans would be easier to control. So longer as colonial expansion was restricted to territory agreed upon in treaties, the costs of protecting the frontier should be minimal - but the London officials thought those costs should be covered by the colonies, since they were the beneficiaries.

The simple taxes on stamps, etc. were reasonable if you thought the colonies should pay for their defense - but if you thought England was exerting new controls on independent assemblies that had already paid more than their fair share, then the taxes were intolerable and were just the first wave of new controls that threatened the freedoms of the English settlers in America.

In 1775, the natural ties of loyalty binding Virginia's gentry to England snapped. England was seen as a threat to the gentry's ability to make and retain wealth. The perception became clear that unconstrained taxes and mercantilist policies would steadily drain wealth out of America. People in Great Britain, 3,000 miles away, would benefit from the hard work of colonists to clear the forests and develop the iron and other mineral assets in North America.

Colonial leaders in the Virginia General Assembly recognized that the legislature would have minimal influence. Decisions would be made in London by appointed officials who gained their positions through family connections and personal relationships, not through demonstrated capabilities or any concern for enhancing economic development in the colonies.

The impact of policies on Virginia would be given minimal consideration compared to the impact on business interests in Great Britain. As demonstrated with the attempt to rescue the East India Company in 1773, members of Parliament had personal interests in the businesses that would benefit from official policies. Those personal interests skewed the decisions.

Parliamentary policies would swing back and forth inconsistently, as demonstrated by the military decision to withdraw from Fort Pitt and Fort Chartres while the Proclamation of 1763 stayed in force. Centralization of policies for trading with western tribes after the French and Indian War was replaced after the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix with a decision to decentralize treaty-making and enforcement of trade deals to the separate colonies As a result, no one could enforce the proclaimed restraint on settlement. Disruption of the traditional Native American hunting grounds was likely to trigger more warfare like Pontiac's Rebellion.

The Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act showed that England was a threat to western expansion by colonists. That was a major concern to the cash-poor but potentially land-rich gentry. Grand dreams of getting rich from western lands could not become true, and even land grants promised to veterans of the French and Indian War were not getting approved, so long as British officials were making the decisions.

The grant made to investors in the Ohio Company in 1749 and the proposed Mississippi Company organized in 1763 were getting rejected in London. At the same time, Pennsylvania investors in the Great Ohio Company were expected to receive 20,000,000 acres west of the Ohio River to create the new colony of Vandalia.

Benjamin Franklin concluded after a January 1774 grilling by the Privy Council that the British leaders based in London had only a narrow perspective that prioritized maintaining the wealth and status of the existing English elite. So long as King George III and Parliament viewed American colonists as second-class members of the empire, Franklin saw no opportunity for the wealthy and educated elite in the American colonies to rise above second class status.

Franklin had spend years enjoying the cultural opportunities in London. As a wealthy man with an international reputation, he should have been a strong advocate for retaining the existing social structure and economic system. However, the experience:1

To the Virginians, English behavior towards Ireland already demonstrated its willingness to over-tax a colony in order to benefit the mother country. This concern had a personal, as well as colonial, facet as well. The debate after the 1783 Treaty of Paris over paying back the planters' pre-war debts to English merchants suggests that some planters may have preferred to declare independence from England rather than declare bankruptcy to satisfy English merchants.

A "rebel" or an "insurrectionist" is one who tries to overturn existing authority, but fails. A "revolutionary" is one who succeeds in that quest, establishing a new form of authority to replace the old.

The Virginians who fought in 1776-83 are honored nationally as Revolutionary War soldiers. However, the Virginians who fought a second war of independence 80 years later in 1861-65 (as the Confederates described it) are "rebels." Some describe Virginians who fought for the Confederate States of America such as Robert E. Lee as "traitors."

When the accumulated history of the 1861-65 conflict was published as the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, the title was one more indication that a rebellion had failed to become a revolution.

There was no guarantee in 1775 that the American Revolution would succeed. The colonies were nearly defeated by the British military and their Native American allies at several points between 1776-1781. British forces raided Virginia several times between 1780-81, and the American capacity to resist was minimal. Only in September, 1781, when a large percentage of the Continental Army and French forces marched to Virginia, was it possible to limit where General Cornwallis could march.

The nationalistic patriotism and flag-waving on July 4 each year obscures the extreme risks taken by colonial leaders. Had Cornwallis continued to march throughout the southern states rather than encamp at Yorktown and await reinforcement (as ordered), modern students might be referring to famous Virginians of that time period as rebels/insurrectionists/terrorists rather than as "Founding Fathers." George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and others could have been hung as traitors, with their heads displayed on poles at the Capitol in Williamsburg.

The gentry nearly lost control of the revolutionary movement in the summer of 1775. The Second Virginia Convention met at the Henrico Parish Church (later named St. John's Church) in Richmond between March 20-27, 1775. After a rousing speech by Patrick Henry, the delegates decided to put the colony "in a state of defense" and support the creation of independent companies across the colony. Those companies would provide a military force to replace the county militias.

The gentry in the colony had controlled the militia companies in each county. Officers in the colonial militia had been appointed by the governor; all were members of the upper class. Until 1775, most of thr men attending militia training in counties east of the Blue Ridge were relatively wealthy. They could afford to purchase the required weapons and to dedicate the time required to participate in a militia gathering.

In 1775, men who did not own land flocked to join the independent companies that replaced the official county militias. The demographics of organized armed men in Virginia flipped. The independent companies elected their own officers; they were not inclined to elect men who were accustomed to exerting authority and imposing discipline.

Patrick Henry demonstrated that one person without authority could direct the volunteers in those independent companies to march towards Williamsburg. An armed mob was prepared to seize control of the government. The men were angry after Governor Dunmore had the gunpowder removed from the Magazine, and they were out of control - at least the traditional control of the colonial leaders in the House of Burgesses. A face-saving gesture of receiving payment for that gunpowder was arranged and Patrick Henry dispersed his followers but traditional law and order had broken down.

In the middle of 1775 the landowners in Virginia were at risk of losing their long-standing control over society. "Soft power" had always been implemented successfully because men with wealth and status were respected; deference was voluntary except in the case of enslaved workers.

The elite had no police force to maintain authority over the white farmers. The slave patrols could not be repurposed to protect the mansions of the First Families of Virginia from the white farm workers they employed. Armed men roamed around Williamsburg in May and June, 1775 without any commanders who could control their behavior.

After Governor Dunmore fled the capital on the night of June 8-9, men broke into the Governor's Palace to remove the weapons on the walls. They ignored direction from the burgesses to stay out of the palace. They also seized tax revenues which had been accumulated by royal officials. Members of the House of Burgesses were powerless to stop the theft of colonial assets.

Once the lower classes in Virginia were no longer willing to defer voluntarily to the small number of people in the upper class, the next phase in the summer of 1775 could have resembled Bacon's Rebellion in 1676. Assets of the wealthy families could have been seized and redistributed, as were the colonial assets. Mobs could have occupied the houses of the wealthy, drained the wine cellars, and destroyed property in an uncontrolled rebellion.

Actions by the Third Virginia Convention in July 17-August 26, 1775 enabled the gentry to regain control. The independent companies were abolished and replaced by two Virginia regiments. By the end of September, 1775, William Woodford had been appointed colonel of the Second Regiment and captains had been appointed to command companies.

Those captains were not elected by the soldiers who enlisted in the companies. The Committee of Safety, which served in place of the governor, Governor's Council, and General Assembly after the Third Virginia Convention concluded, appointed the officers. The convention established a substantial difference in pay between officers and men. That was part of a conscious effort to ensure that officers would have a higher status, which was required for them to control the actions of the soldiers.

Soldiers unwilling to accept the authority of the officers and enlist in the new companies went home to their farms. That brought an end to the threat of a mob in Williamsburg.

Patrick Henry was appointed Colonel of the First Regiment, ensuring he would not assume the role of Nathaniel Bacon, and initially the First Regiment was kept in reserve. The Second Regiment was sent to Great Bridge to confront Governor Dunmore. The Committee of Safety did not desire for Patrick Henry to become a military hero by winning the first open engagement against Governor Dunmore. Instead, Colonel Woodford received credit for the victory at Great Bridge.2

Not all of the gentry chose to support rebellion against Great Britain. A substantial number of Virginians (perhaps 20-25%) remained loyal to the British Crown and Parliament during the American Revolution. The shop keepers from Scotland working for English merchants, Anglican ministers, and most royal appointees chose to sail back to England.

A few wealthy Virginians also fled. Peyton Randolph, speaker of the House of Burgesses, chaired the first Virginia Convention and the first Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774. His brother, John "the Tory" Randolph, chose to sail to England. In addition to conservative gentry members such as John Randolph Grymes, who provided Governor Dunmore his last refuge at Gwynn's Island in Mathews County in 1776, the royal governor received support from many of the residents in Norfolk in 1775.

So long as the conflict with policies coming from London was an intellectual debate, most Virginia politicians sought peaceful resolution of their grievances. For months after the April 1775 battle at Lexington and Concord and the battle at Bunker Hill in June, physical conflict in Virginia was minimal. The Royal Navy finally attacked Hampton and Governor Dunmore issued his Emancipation Proclamation in November, 1775. That proclamation forced the colonists to choose sides.

The governor's threat to arm the enslaved workers and lead them in battle against the white Virginians, as occurred at the Battle of Great Bridge in December 1775, was the turning point. Those trying to stay neutral/uninvolved had to choose if they would continue to support the royal government which had been in charge since 1624.

From the British perspective in 1775, "patriots" were those who supported the existing royal government. Others, such as Peyton Randolph and the other delegates at unauthorized Virginia conventions, were insurrectionists, rioters, rebels, and revolutionaries. They were breaking the law, and those who supported traitors should suffer the consequences for their treason. Anyone in Virginia trying to stay neutral regarding allegiance to King George III faced the risk of being treated as "unpatriotic," once Governor Dunmore returned to Williamsburg.

After Dunmore circulated his Emancipation Proclamation, small farmers who were not fond of the wealthy gentry in Tidewater realized they now faced an existential threat. If the British regained control, thanks to a military force composed primarily of black men who had been enslaved, then the entire social and economic structure could be overturned. What little wealth had been accumulated by the lower classes, especially those who owned some land, would be at risk if Lord Dunmore re-occupied the Governor's Palace.

The pamphlet Common Cause provided both emotional and rational justification for choosing to rebel against British authority. Traditional leaders organized new political structures, initially to enforce the non-importation agreement and then to suppress loyalists. The burning of Norfolk at the start of 1776 demonstrated to everyone that Virginia's revolutionary leaders were willing to compel support for the rebellion, and to use violence to destroy all the property of anyone who was not clearly supporting rebellion.

By the time Virginia's leaders had declared independence and adopted a state constitution in the middle of 1776, the majority of white Virginians had chosen to support revolution. The remainder, the loyalists, were too scattered and too intimidated to organize an effective resistance.

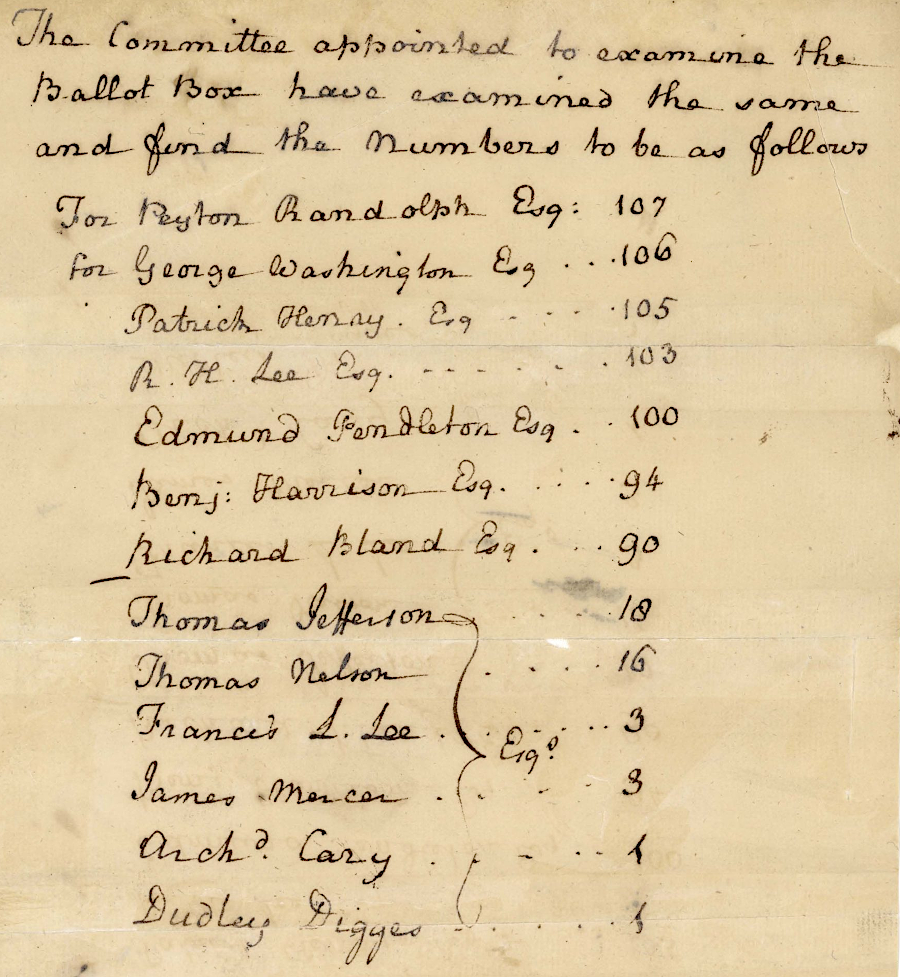

Virginia delegates sent to the Continental Congress were all wealthy, with much to lose by rebelling

Source: Library of Virginia, Report of Committee to examine ballot box for election of delegates to congress in Philadelphia (March 25, 1775)

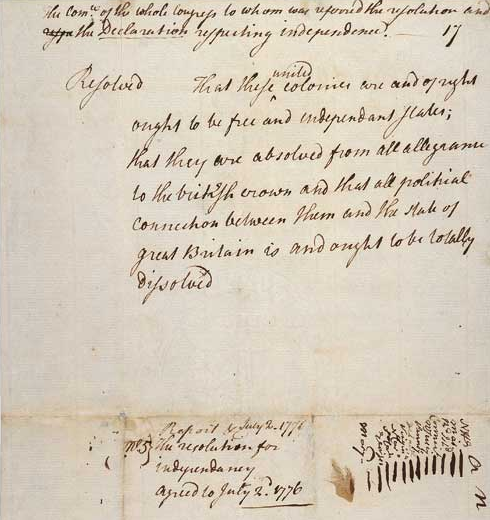

The national Declaration of Independence was written after the Fifth Virginia Convention had already acted on May 15, 1776. The Fifth Virginia Convention, all of whose members were part of the top economic and social layers of society, instructed its representatives in Philadelphia to propose independence. Richard Henry Lee submitted the Virginia proposal for independence to the Continental Congress, as instructed, on June 7, 1776.

The Virginia General Assembly approved George Mason's Declaration of Rights on June 12 and the state's first constitution on June 29, 1776. The Second Continental Congress voted to declare independence on July 2, and approved its now-famous declaration two days later.

on June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee initiated the process in the Continental Congress that led to the colonies declaring independence from Great Britain

Source: National Archives, Lee Resolution (1776)

Technically, Virginia was an independent state even after it ratified the Articles of Confederation in 1778. The new national government became operational in 1781 after Maryland's ratification, but it was a loose confederation whose members retained almost all government authority in 13 separate states.

The first attempt at a national government demonstrated that decentralized authority was ineffective. An armed insurrection in Western Massachusetts in 1786-1787, Shay's Rebellion, led key national leaders to view the situation as comparable to the loss of control in Williamsburg in mid-1775. Once again, the wealthy elite would have to reinvent government.

The failure of that first national union under the Articles of Confederation led to a peaceful revision of the contract between the states. In 1788, enough states ratified the US Constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation, and the current Federal government was established at the beginning of 1789.

A successful war for independence and creation of a lasting government was not preordained in 1774. The Virginians who joined with Lord Dunmore and remained loyal to their country, which was England rather than Virginia, were opposed to an independent "America." Had the British suppressed the rebellion, leaders such as George Washington could have been hung as traitors and an occupying army with black soldiers could have taken control of Tidewater plantations owned by defeated revolutionaries.

Had the royal governor Lord Dunmore managed to stay in his colony longer, or if British forces had raised the standard of the king in western Virginia and invited the frontiersmen to rally to the loyalist cause, there is a chance that the July 4 parades would have to acknowledge that only one-third or so of the colonial Virginians strongly supported the Revolution.

The planter elite, the gentry who controlled the colony as members of the House of Burgesses, county courts, and parish vestries, were the most committed to separating from Great Britain. The richest planters were also the ones who owed the greatest debts to British merchants, and recognized most clearly that the colony was in an economic squeeze which would continually transfer Virginia wealth to the home country.

Perhaps one-third of Virginians in 1775 may have chosen to be loyalists if community pressure had allowed free expression, especially if enslaved people had been able to reach the British lines to obtain promised freedom. There are no polls to substantiate statistics, but perhaps one-third to two-thirds of Virginia's white residents may have been uninterested in risking their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor in a fight that would maintain the hegemony of the Virginia elite.

The great military success of the revolutionaries was not on the battlefield. It was winning the "hearts and minds" of so many Virginians. That facilitated acquiring supplies despite currency which was rapidly inflating, recruiting troops, and maintaining a willingness to fight between 1775-1781 despite few victories.

The merchants in Virginia recognized that war would disrupt their business, and the potential for total loss was greater than the potential for profit. The Scottish traders in Norfolk were economically linked to the mercantile system of England. So long as the colonies were economically dependent upon the mother country, and the Royal Navy enforced the Navigation Acts and prevented direct shipment of Virginia-grown tobacco to French and Dutch ports, the Scots in Norfolk would make money as middlemen.

The Scottish merchants did not have a monopoly on shipping Virginia tobacco to Glasgow and other British ports, but they had a high percentage. By the 1770's ships sailed directly to just the largest plantations to load tobacco, plus the few towns such as Alexandria. Only the largest planters could maintain a direct relationship in England, with an agent in London serving as a banker/buyer for their orders.

The Scots recognized that an independent Virginia (perhaps allied with other colonies, perhaps not...) would allow greater competition and cut deeply into their profits. The economic interests shaped political preferences for loyalists as well as revolutionaries.

In the backcountry, particularly west of the Blue Ridge in Montgomery County, there were pockets of loyalists. Direct threats by patriots - the American Revolution was a civil war - prevented loyalists from speaking out or gaining political control of any Virginia jurisdiction. When Lord Dunmore fled Williamsburg in 1775, the "rebels" gained control of local government institutions and built a new structure starting with five conventions and finishing with a new state constitution. The gentry that once controlled the House of Burgesses were elected to serve in the new House of Delegates and the State Senate, and were able to set tax policies that reflected their economic interests.

The western Virginians were had few economic ties to England. EWhen they purchased manufactured goods or sold agricultural products, westerners dealt with merchants in the port cities of Tidewater or in Philadelphia. Transportation costs across the Piedmont and the Blue Ridge made it uneconomic to purchase enslaved workers and grow large quantities of tobacco or other cash crops. Profits from crops grown west of the Blue Ridge were consumed by high shipping costs. In contrast, farmers in the Piedmont west of the Fall Line but east of the Blue Ridge had easier access to navigable rivers leading to a Chesapeake Bay port.

The support for England by western settlers was not based on economic dependency upon England. West of the mountains, people were reluctant to partner with the rebelling Tidewater gentry who did not support western interests sufficiently. Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson worried about the loyalty of westerners when they served as Virginia's first two governors.

Revolution was not a good economic decision for slave-based Virginia plantations shipping tobacco overseas, at least in the short run. Infrastructure was destroyed and "human capital" was killed or wounded during fighting and by disease during encampments. Instead of planting crops in 1775-1783, farmers were employed as soldiers who produced no products. The state and national governments struggled to pay the soldiers, so American armies did not generate economic benefits comparable to the defense-industrial complex of modern times.

During and after the revolution, tobacco, wheat, and other farmers had to find replacements for British buyers of their crops. Economic recovery did not occur until after a new Federal government, based on the US Constitution, established trust in Europe and the Caribbean that Americans would pay their debts. The wealthy gentry of the mid-1770's may have retained political power through the American Revolution and prevented British officials from imposing high taxes, but the economic loss after 1775 was substantial:3

Revolution also was not a good thing for the free laborers and small farmers on the western edge of European civilization. Settlers west of the Blue Ridge were taxed by the House of Burgesses, but poorly represented in it. Few counties were created west of the mountains until 1774, so few representatives were sent from the backcountry to Williamsburg. As a result of the American Revolution, non-Anglican residents living west of the Blue Ridge were no longer burdened by taxes to support an established church. However, those farmers were burdened by an unfair load of the taxes established by a General Assembly in which the western residents were under-represented.

The colonial (and, after 1776, state) legislature dominated by Tidewater slaveowners ensured that taxes on human "property" were minimized. Landowners paid heavy taxes while slaveowners did not. Westerners with few enslaved people subsidized a Virginia government controlled by Tidewater planters, a pattern that persisted until the Civil War started in 1861.

The First Families of Virginia - the Lees, Carters, Randolphs, and others who could afford to build mansions in Tidewater before the American Revolution - kept control of Virginia's economy and politics after the American Revolution. Those families did not lose their excessive influence until the end of primogeniture and entail, which gradually led to the breakup of the large plantations.

Changes in the state constitution in 1830 and 1851 still kept political power east of the Blue Ridge. The issue of taxation without adequate representation continued until the end of slavery, after which that form of "property" was no longer taxed.