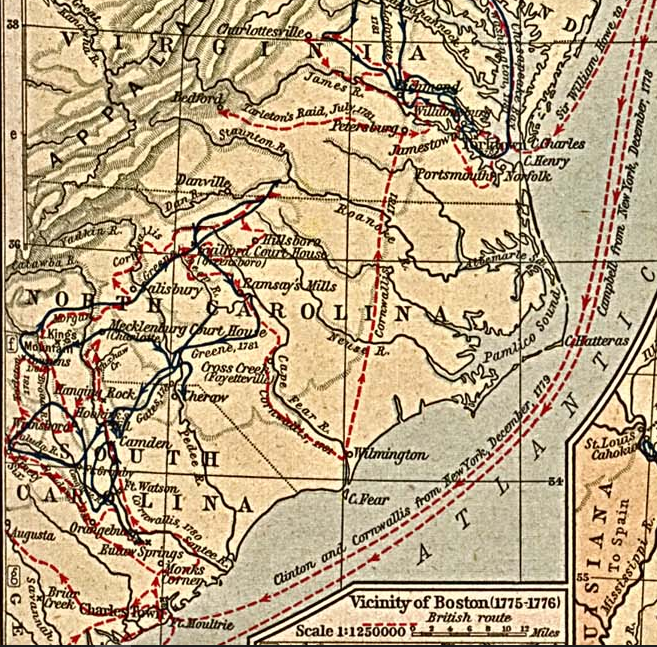

in 1781 Cornwallis marched from Wilmington to Petersburg, then to Portsmouth and finally to Yorktown

Source: Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection, Campaigns of the American Revolution, 1775-1781 (in Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1923) and Library of Congress, Campagne en Virginie du Major General M'is de LaFayette: ou se trouvent les camps et marches, ainsy que ceux du Lieutenant General Lord Cornwallis en 1781

The French and American victory at Yorktown started with a major defeat at Charleston, South Carolina in May, 1780. It was one of a long string of defeats, after which the Continental Army led by George Washington managed to survive but could not force the British to end the war.

In 1775-78, the Revolutionary War was fought primarily in the north between Quebec and Pennsylvania. The Americans failed to capture Quebec at the end of 1775, but did force the British to evacuate Boston in 1776. General William Howe organized his army at Halifax, and then with his brother Admiral Richard Howe captured New York City. They made it the primary British base for the rest of the war.

George Washington led the defeated Continental Army through New Jersey and across the Delaware River. At the end of 1776 he crossed the river and won victories at Trenton and Princeton that built morale, spurred recruitment for his army, and forced the British to evacuate New Jersey.

Washington spent the rest of the early 1777 winter at Morristown. Both sides waited until spring before choosing to engage in large battles, when there would be enough forage for horses to be able to pull wagons and artillery to a fight.

In October 1777, General Horatio Gates won a stunning victory at Saratoga, capturing the British Army led by General John Burgoyne that was marching south from Canada via the Hudson River in hopes of isolating Massachusetts from the other newly-independent states. The success at Saratoga led to France becoming an open ally of the United States of America.

Also in 1777, General Howe sailed an army from New York into the Chesapeake Bay, landing at the mouth of the Elk River. After he defeated George Washington at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, the British occupied Philadelphia. Washington led his army to Valley Forge for the 1777-78 winter camp.

Some Continental Army officers compared the success of Horatio Gates at Saratoga to the failure of George Washington at Brandywine. Led by Brigadier General Thomas Conway, they hinted that the Continental Congress should replace the losing general with the winning one as commander-in-chief. Washington mobilized his support in the Continental Army and Congress, and the "Conway Cabal" collapsed.

The entry of France into the war forced a change in British strategy. The Continental Army had managed to survive, and public support for the rebellion continued despite British capture of the two largest cities in North America. Continuing the cat-and-mouse game with Washington and trying to win more military victories in the northern states would risk exposure to a French fleet capturing New York.

In 1778, Sir Henry Clinton replaced Lord Howe as British commander of land forces, and the British shifted their focus to the southern states. They abandoned Philadelphia and concentrated at New York. Offensive operations targeted Savannah first, capturing that Georgia city in December 1778. Georgia became the first state to be stripped away and returned to colonial status.

A French and American siege to recapture Savannah failed in 1779. The British then captured Charleston, South Carolina. When General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered in May, 1780, the potential was clear for the British to energize Loyalists and retake all the southern states. The "southern strategy" was succeeding.

Sir Henry Clinton returned to New York, and left General Charles Cornwallis in Charleston to recapture the south. Col. Banastre Tarleton defeated the Virginians fleeing north at Waxhaws on on May 29, 1780. Lord Cornwallis overwhelmed newly-arrived Continental Army forces and local militia led by General Horatio Gates at Camden on August 16, 1780.

The British strategy brought several thousand "Redcoats" and Hessian soldiers to South Carolina. They could seize fortified locations and win fixed battles with Continental Army troops, but loyalists had to take control of the countryside and defeat isolated bands of partisans and militia.

That scenario failed after a loyalist army led by Patrick Ferguson was annihilated by American forces at Kings Mountain on October 7, 1780. The victory by volunteers from west of the Blue Ridge, the Overmountain Men, left Cornwallis with the ability to take his army anywhere he wished to go in the Carolinas, but unable to control the territory after he left. Loyalists would welcome the arrival of the British troops, but would not join the fight in sufficient numbers. Recruitment of loyalists was not helped after Americans under General Daniel Morgan defeated Col. Banastre Tarleton's dragoons at the Cowpens on January 17, 1781.

Cornwallis chose to go north, seeking to engage the next set of Continental troops led by General Nathaniel Greene. Greene engaged in a war of attrition against the British, avoiding major engagements but steadily reducing the British forces. The two armies raced to the Dan River, which provided Morgan with an effective defense barrier. Cornwallis withdrew to Guilford Courthouse, where Greene chose to fight a major battle. The British won a technical victory because they controlled the battlefield afterwards, but Cornwallis was forced to march to Wilmington in order to get more supplies.

From Wilmington, he led the British army to Petersburg. Greene's army depended upon troops and supplies brought from Virginia, and Cornwallis intended to interrupt the supply chain. He could not catch Greene, but he might catch his food and ammunition.

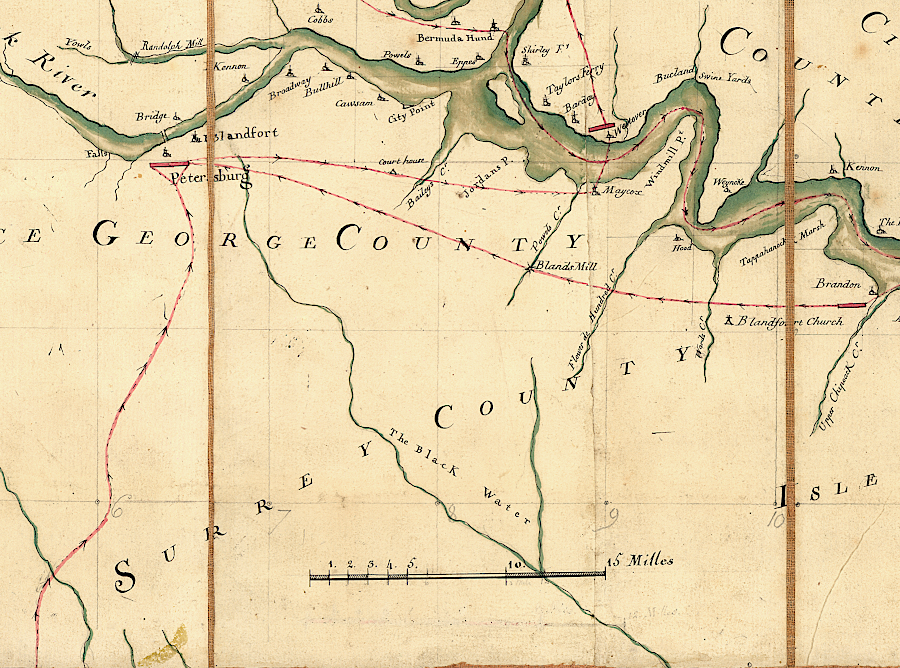

There were already British forces in Virginia. Benedict Arnold had arrived in the Chesapeake Bay at the end of 1780. He sailed up the James River and unloaded at Westover on January 4, 1781. He marched his British troops, loyalists in the Royal American Regiment (Robinson's Corps), and Hessians led by Captain Johann Ewald to Richmond. After the capture of Virginia's capital on January 5, Arnold's force went upstream to Westham where they destroyed cannons and gunpowder. There were no major civic buildings in the new capital, no capitol or governor's mansion to destroy. There were no significant officials to capture either; Governor Thomas Jefferson and the General Assembly fled west to Charlottesville.

Arnold did not follow; instead, he returned to Portsmouth on January 19, 1781. Two months later, General William Phillips arrived and took command. Near the end of April, he moved upstream and then to Petersburg and Manchester. Phillips was planning to return to Portsmouth when he received word that Cornwallis would move from Wilmington to Petersburg. Cornwallis arrived at Petersburg in May, over a week after Phillips had died from disease. Benedict Arnold turned over the command, and Cornwallis quickly sent him back to New York.

Cornwallis marched north to the North Anna River, then directed forces to Charlottesville to capture political leaders and Point of Fork to capture supplies. The Marquis de Lafayette avoided any major engagement, even after being reinforced by troops led by "Mad Anthony" Wayne. Cornwallis's raid into the Piedmont was the first major British invasion west of the Fall Line, but his activities did not provide the British any substantial military benefits.

Cornwallis marched through Virginia's Piedmont before planning to camp at Portsmouth, and then going to Yorktown

Source: Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library , MARCH of the ARMY under Lieut:t General EARL CORNWALLIS in VIRGINIA, from the JUNCTION at Petersburg on the 20.th of May, til their arrival at Portsmouth on the 12.th of July 1781

The escape of nearly all members of the General Assembly to Staunton and Jefferson's flight to Bedford Forest left Cornwallis with no major rebel captives. He did gather up enslaved men and women and plundered plantations, including Governor Jefferson's at Elkhill in Goohland County, but found no reason to stay west of Richmond. In mid-July, Cornwallis returned to the fortifications at Portsmouth.

Cornwallis plundered Jefferson's plantation at Elkhill, but that damage had no military benefit

Source: Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library , MARCH of the ARMY under Lieut:t General EARL CORNWALLIS in VIRGINIA, from the JUNCTION at Petersburg on the 20.th of May, til their arrival at Portsmouth on the 12.th of July 1781

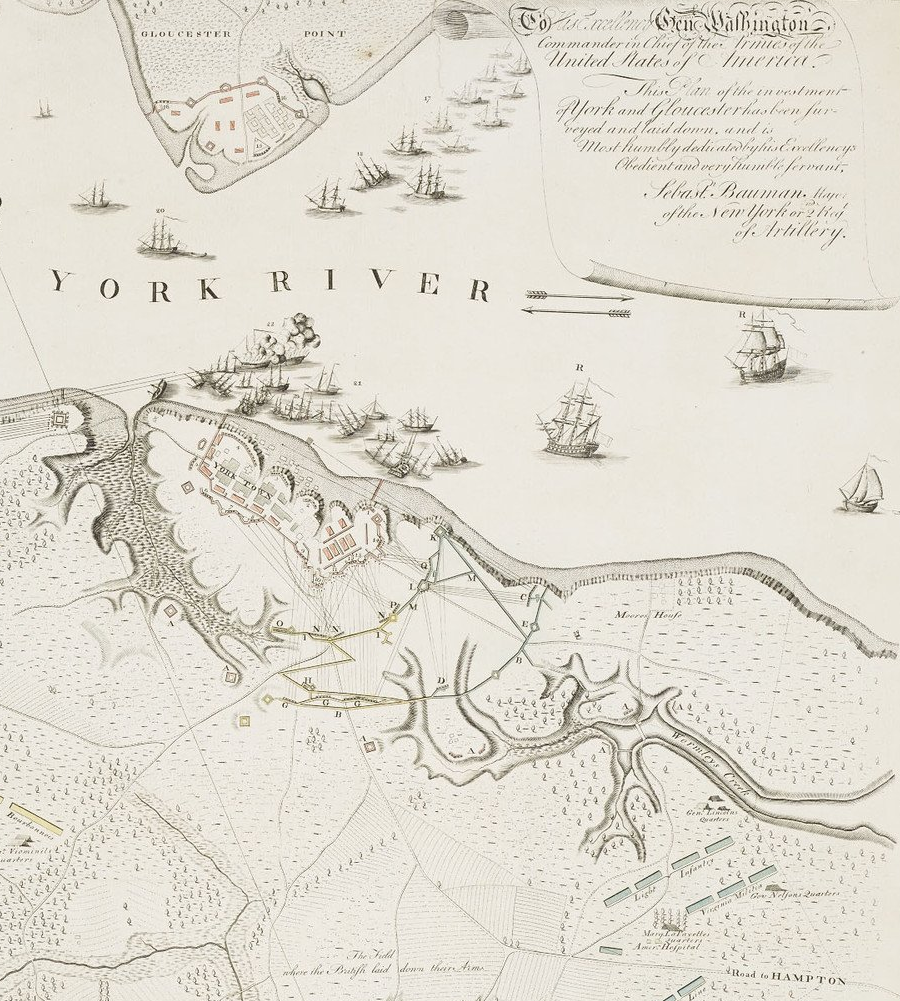

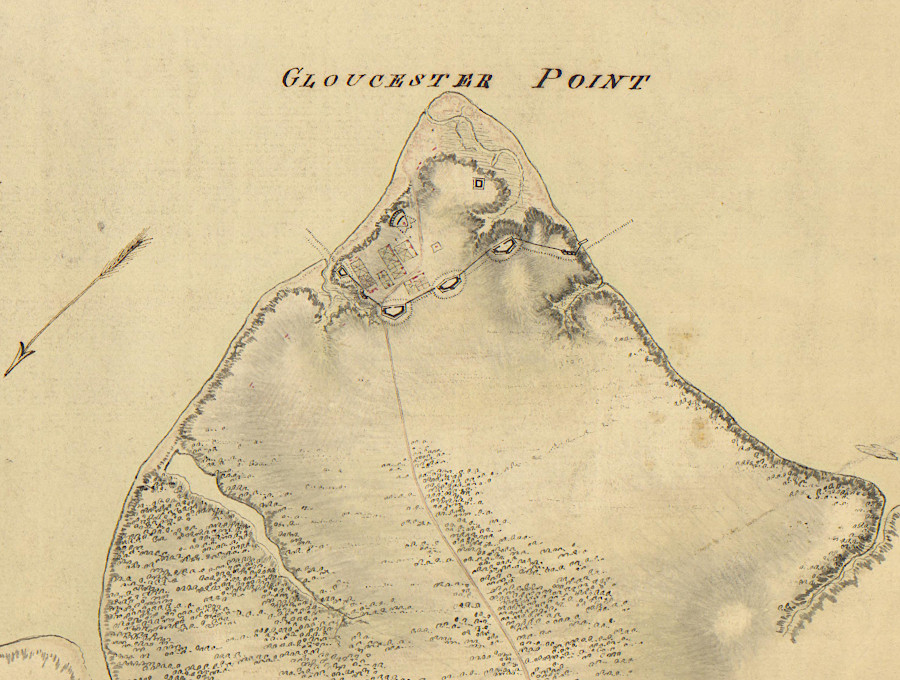

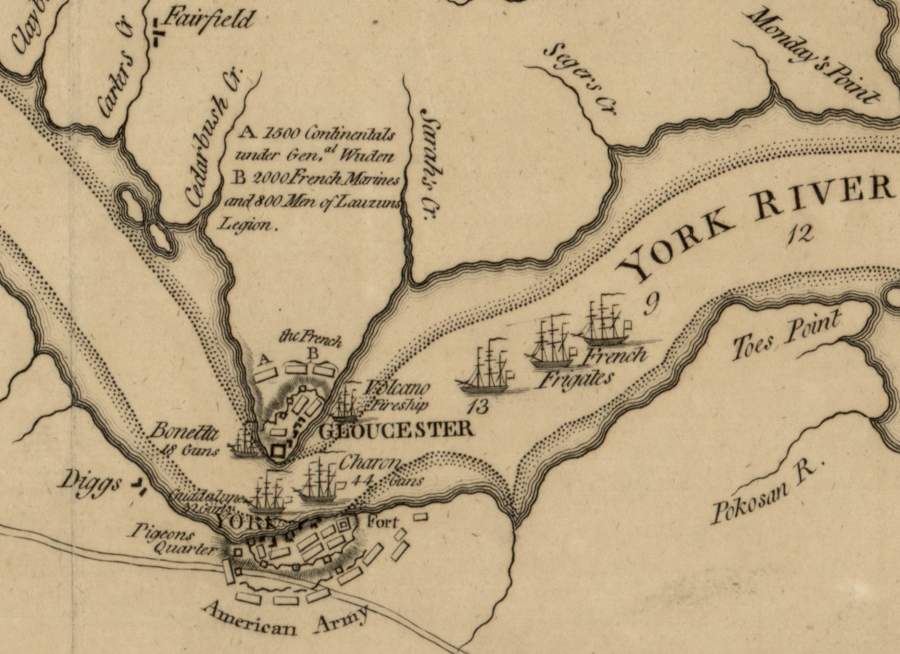

Cornwallis received orders from Gen. Henry Clinton to establish a defensive base in Virginia, with Old Point Comfort as a suggested location along with Williamsburg and Yorktown. Old Port Comfort lacked fresh water and Williamsburg was inland of both the James and York rivers, so Cornwallis chose to create a fortified camp at Yorktown. To prevent Virginia or French ships from sailing past Yorktown and attacking from that angle, he also fortified Tyndalls Point/Gloucester Point and stationed .

The British settled occupied Yorktown and Gloucester on August 1-2, 1781. The last forces left Portsmouth on August 18, bringing the British total at Yorktown to 6,000 British and German soldiers, plus sailors and Loyalists.

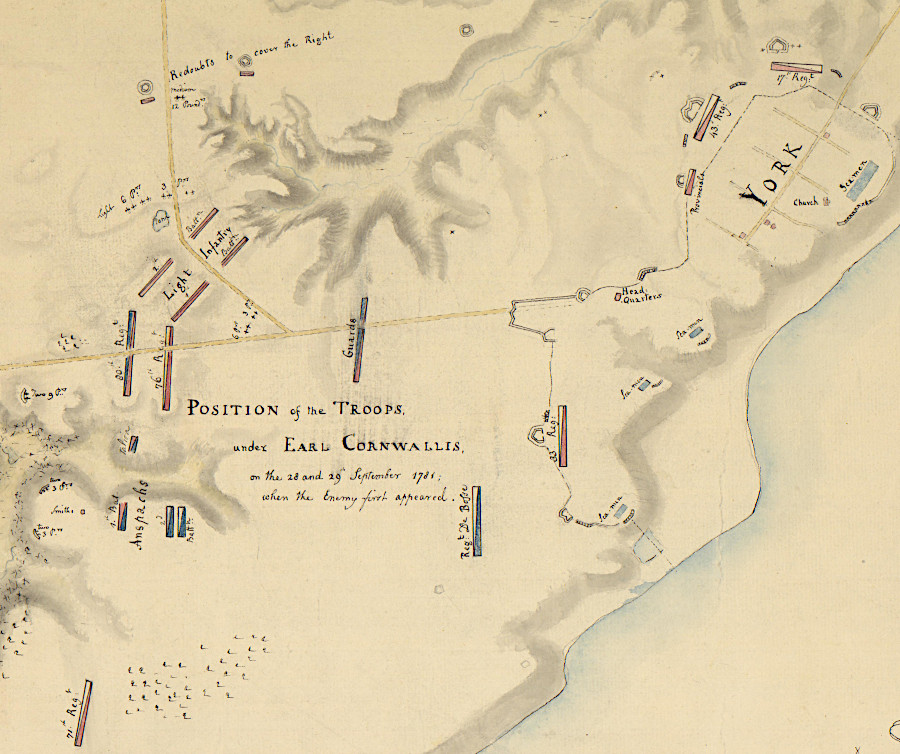

Lord Cornwallis prepared trenches and redoubts around Yorktown for temporary defense, in anticipation of reinforcements from New York City

Source: University of Michigan, William L. Clements Library, Position of the troops under Earl Cornwallis on the 28 and 29th September 1781; when the enemy first appeared

In between, on August 14 the French forces in New York received word that French fleet in the Caribbean would sail north to provide support until the middle of October. George Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau decided to abandon plans to attack the British in New York; instead, they would march to Virginia and try to capture Cornwallis's army. That option was feasible only if the French ships could prevent Cornwallis from being supplied or evacuated.

The American and French army had reached Philadelphia before Clinton realized their plan. The powerful French fleet from the Caribbean led by Rear Admiral the Comte de Grasse arrived at the Chesapeake Bay at the end of August. It ferried troops to Williamsburg, without disturbance from British ships stationed at Yorktown, to reinforce the Continental Army force led by the Marquis de Lafayette. Other French commanded by Admiral the Comte de Barras ships sailed from Newport, Rhode Island with the heavy artillery required for a long siege, assuming Cornwallis could be trapped at Yorktown.

The British sent a smaller number of ships from the Caribbean under Rear Admiral Sir Samuel Hood to chase after the Comte de Grasse. The British ships were unaware of the French-American plans. When Hood saw no French ships at the Chesapeake Bay, he continued to New York to join the British fleet there. Rear Admiral Thomas Graves there added five ships to the fourteen brought by Hood and sailed south, planning to take control of the Chesapeake Bay and ensure supplies could continue to flow to Cornwallis.

the presence of French fleets in the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic Ocean were key to the British defeat in the land battle at Yorktown

Source: Boston Public Library, Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, A plan of the entrance of Chesapeak Bay, with James and York rivers... (1781)

the victory at Yorktown 40 miles inland was determined by the French fleet at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay

Source: Library of Congress, Carte de la partie de la Virginie ou l'armée combinée de France & des États-Unis de l'Amérique... (Esnauts Et Rapilly, 1781)

filling half of an image with the French fleet highlighted their role

Source: Brown University Library, Reddition de l'Armée Angloises commandé par Mylord Comte de Cornwallis aux Armées combinées des Etats Unis de l'Amerique et de France

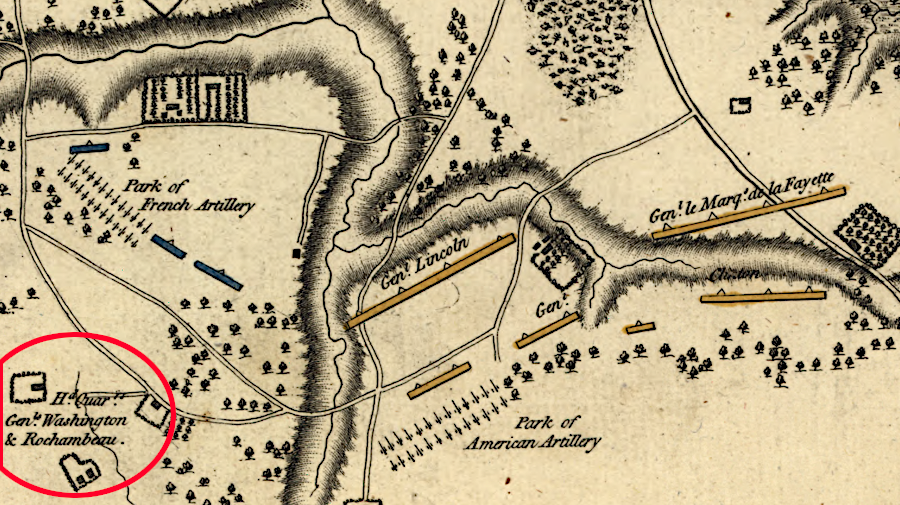

On September 5, the two fleets fought the Battle of the Chesapeake Capes. The smaller British fleet was unable to break through the French line and gain control of the bay, and at the end of the day chose to return to New York. That left Cornwallis isolated. Washington and Rochambeau assembled their 16,000 men, and initiated the siege on September 28.

British ships were trapped at Yorktown and Gloucester Point

Source: Royal Collection Trust, This Plan of the investment / of York and Gloucester (by Sebastian Bauman, 1782)

In the Battle of the Hook on October 3, Banastre Tarleton's cavalry was defeated and forced to return to Gloucester Point. That revealed the difficulty of escaping to the north and cut off supplies needed to feed the horses, and the British then began to kill them.

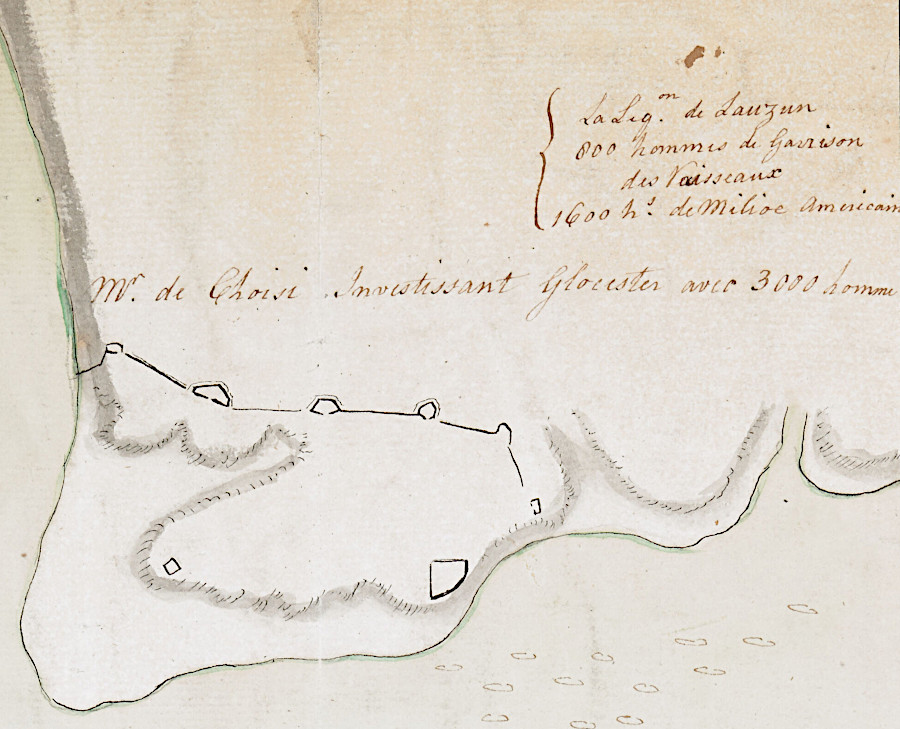

Col. Banastre Tarleton's cavalry could not break through the siege lines at Gloucester Point on October 3, 1781

Source: British Library, French Plan of York Town Virginia (1781)

the British were protected by their fortifications at Gloucester, but could not break through the American/French lines

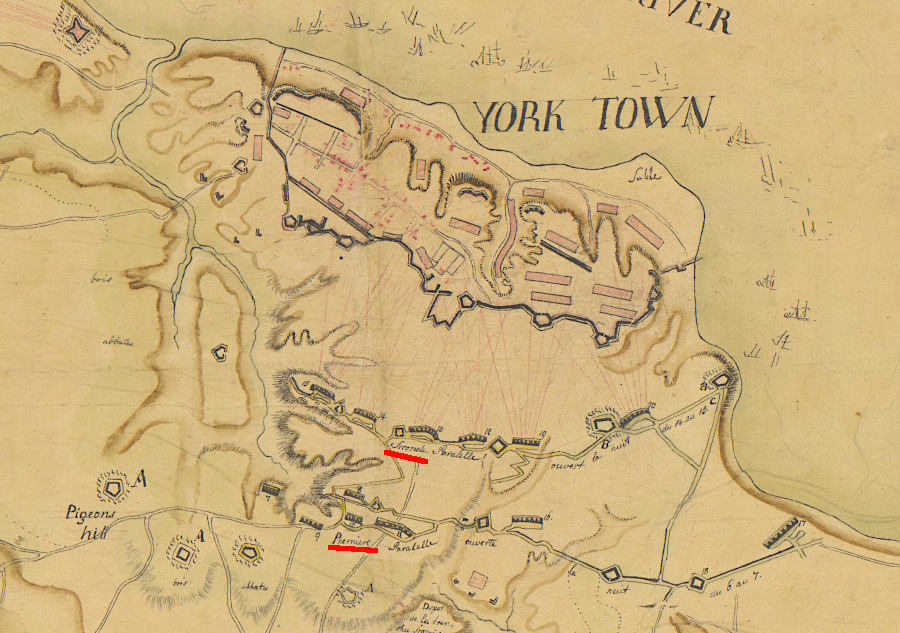

Source: Library of Congress, Plan d'York en Virginie avec les attaques faites par les Armées françoise et américaine en 8bre. (Querenet de La Combe, 1781)

Cornwallis tried to escape the siege on the night of October 16-17. He planned to use his ships to ferry the British forces across the York River to Gloucester and march north up the Middle Peninsula. A storm prevented that movement,

Banastre Tarleton fortified Gloucester, and Cornwallis planned to break through the French/American lines so the British could escape north via the Middle Peninsula

Source: University of Michigan, William L. Clements Library, Plan du siége d'York par l'armée combinée commandée par les generaux Washington et Cte. de Rochambeau

the siege of the French and American armies involved building two line of trenches parallel to the British fortifications, providing protection for the cannon that bombarded Cornwallis' force

Source: University of Michigan, William L. Clements Library, Position of the troops under Earl Cornwallis on the 28 and 29th September 1781; when the enemy first appeared and Carte des environs de York en Virginie avec les attaques et la position des armées Françoise et Américaine, devant cette place 1781

On October 17, 1781, Cornwallis surrendered after nearly three weeks of resistance. The official surrender ceremony was held on October 19.1

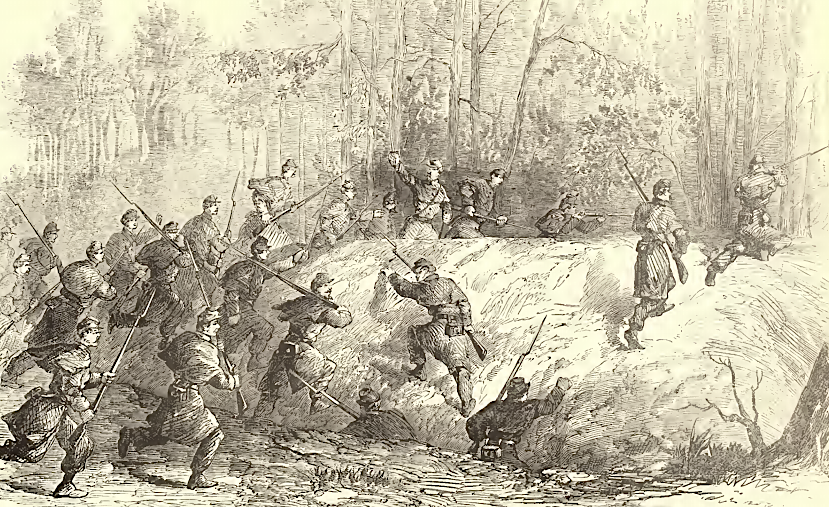

French and American forces seized British redouts in hand-to-hand fighting

Source: Library of Congress, Prise de Yorktown = The taking of Yorktown (by Vve. Turgis, c.1840)

Modern archeologists using scuba gear to dive underwater have explored the British transport Betsy, one of 40 British ships that were sunk by French/American cannon fire or deliberately scuttled by Cornwallis' forces. In 2020, more underwater research on "Wreck 11" retrieved artifacts from what may have been the transport Shipwright. It was one of two transports which collided with HMS Charon before all three ships caught fire and sank.2

Washington had to arrange for the disposition of over 7,000 prisoners, including Loyalists captured with the British and German troops. They were marched to Fairfax Court House, after which one group was sent to Winchester and another group to Fort Frederick in Maryland. The Articles of Capitulation specified:3

One group not protected by the Articles of Capitulation were the enslaved men and women who had fled their homes to seek freedom with Cornwallis's army. The British soldiers had encouraged the enslaved people to run away. The loss of slave "property" punished the rebellious Americans, increased the damage caused by the traveling army, and reduced the capacity of Virginians to engage in war.

By the time he reached Yorktown, Cornwallis had about 4,000 former slaves marching with his army of 7,000 men. So long as the army could "feed off the land" by seizing cattle, pigs, corn and other supplies from Virginia farms, the logistics of supporting the large number of runaways was not a problem. All officers and non-commissioned officers ended up accumulating servants, and:4

As the siege of Yorktown tightened, the British ran low on supplies. Cornwallis ordered that many of the enslaved people had to be expelled from his camp. Those unable to find British officers to protect them were forced to seek shelter in nearby woods, and some ended up in the dangerous no-man's land between the lines.

After the British surrender, freedom was lost. George Washington ordered the runaways to be rounded up and returned to their masters. Many suffered from smallpox; those who survived often carried smallpox back home. A side effect of the American victory was more economic damage to Virginia plantations.5

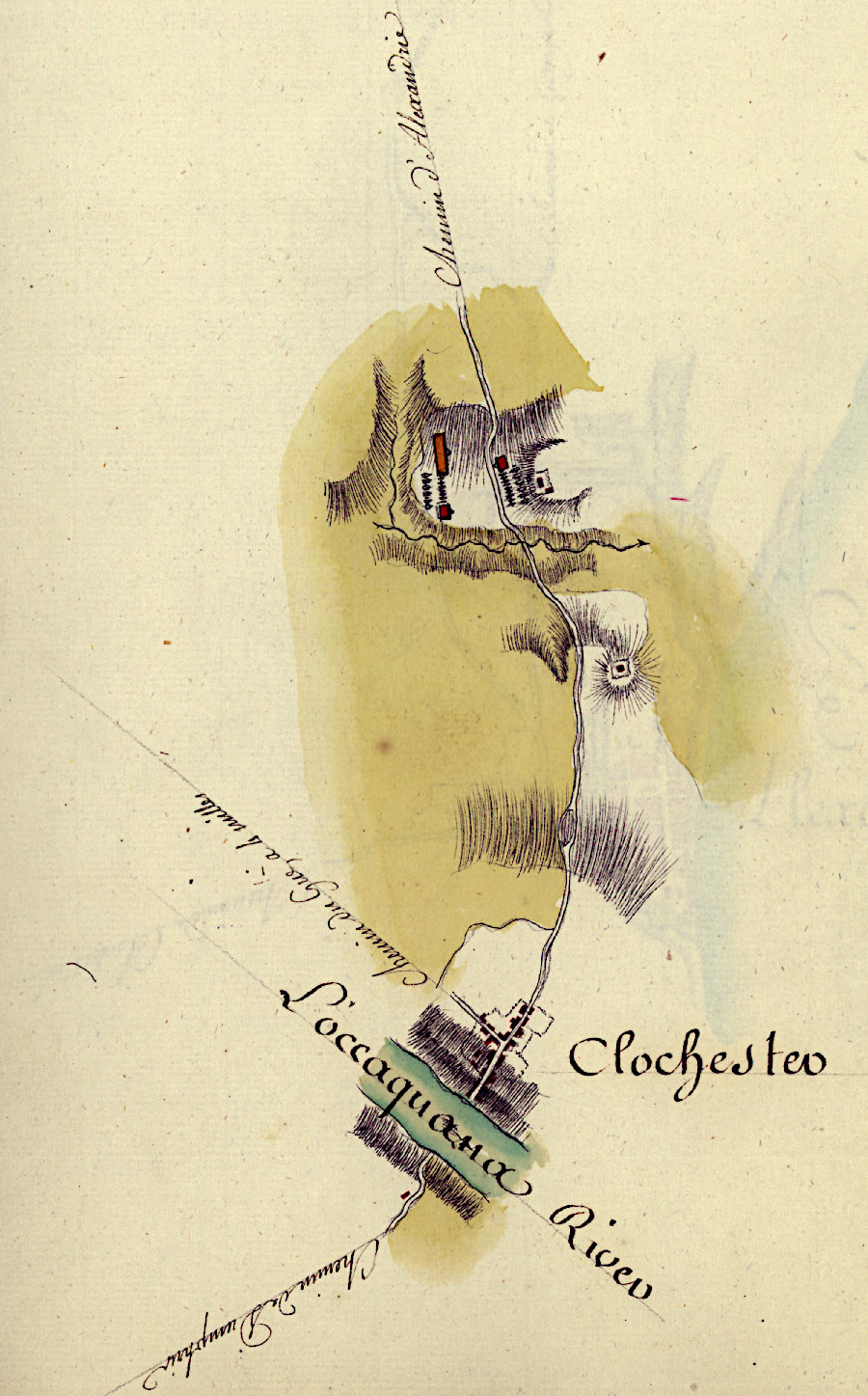

The French army spent the winter of 1781-82 at Yorktown, then marched to Boston between July-December in 1782.

French troops camped at Colchester in Fairfax County when marching back to Boston in 1782

Source: Library of Congress, Amérique campagne - Camp a Colchester (Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, 1782)

French ships and troops were essential to the "American" victory at Yorktown

Source: Library of Congress, A Plan of the entrance of Chesapeak Bay, with James and York rivers (by William Faden, 1781)

French and Virginia troops built trenches, in order to bring firepower close to the British fortifications

Source: National Park Service, Men Digging (painting by Sidney E. King)

to minimize the threat from British guns, most of the trenches were constructed at night

Source: National Park Service, The Siege At Night (painting by Sidney E. King)

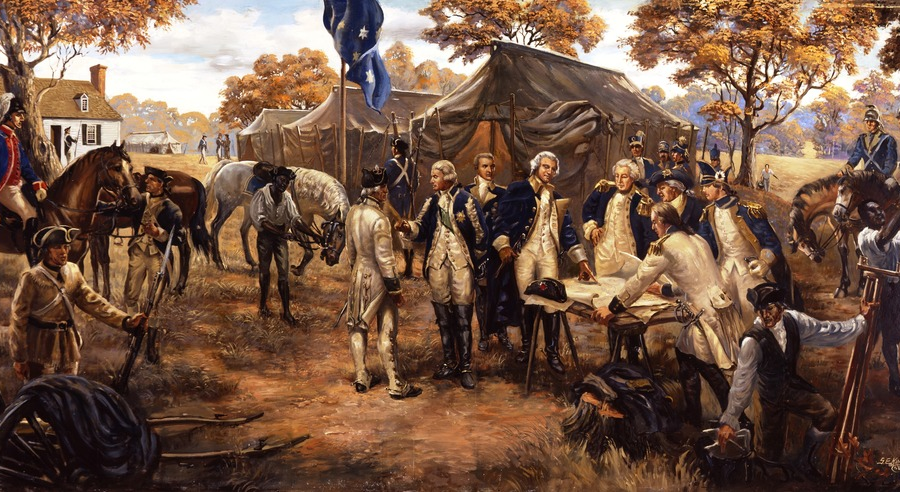

the French provided the key to victory with ships, artillery, and troops, but allowed George Washington primacy in command

Source: National Park Service, Washington's Headquarters (painting by Sidney E. King)

without French equipment and ammunition, the British could have outlasted an American siege of Yorktown

Source: National Park Service, French Artillery Park (painting by Sidney E. King)

the Moore House, site of the negotiations for Cornwallis' surrender in 1871, after General McClellan moved up the Peninsula in 1862

Source: Alexander Gardner, Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War

in 1862, Union troops captured a redoubt built by Confederates on the old Yorktown battlefield

Source: Archive.org, Frank Leslie's illustrated history of the Civil War (p.151)

gabions were constructed in the 1930's to rebuild fortifications at Yorktown

Source: National Park Service, NPS History Collection - Colonial National Historical Park

French and American siege lines were constructed on the southern side of Yorktown

Source: British Library, French Plan of York Town Virginia (1781)

George Washington's headquarters was southwest of Yorktown, behind the French and American artillery parks

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of the battles of the American Revolution, together with maps shewing the routes of the British and American Armies, plans of cities, surveys of harbors, &c., (William Faden, 1845)