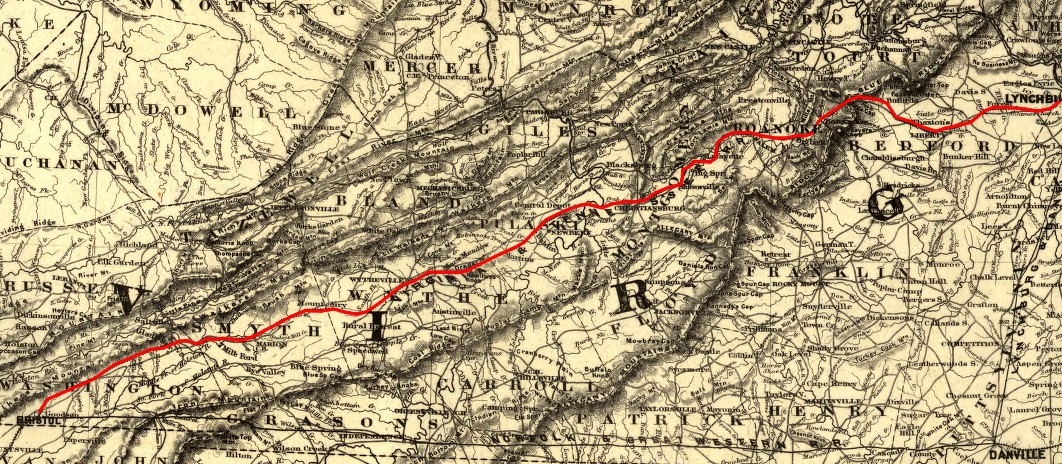

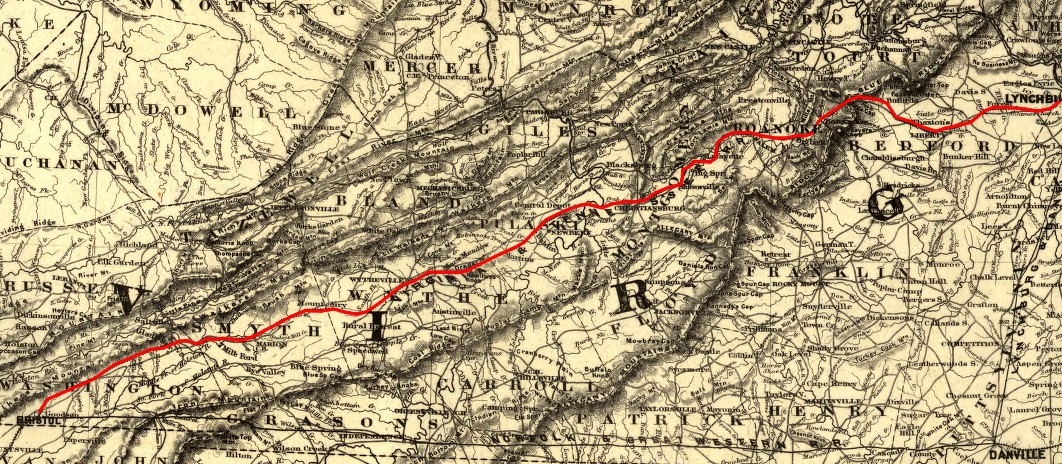

Virginia and Tennessee railroad, built before the Civil War, linked eastern and southwestern Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the Fredericksburg & Gordonsville Rail Road of Virginia

Virginia and Tennessee railroad, built before the Civil War, linked eastern and southwestern Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the Fredericksburg & Gordonsville Rail Road of Virginia

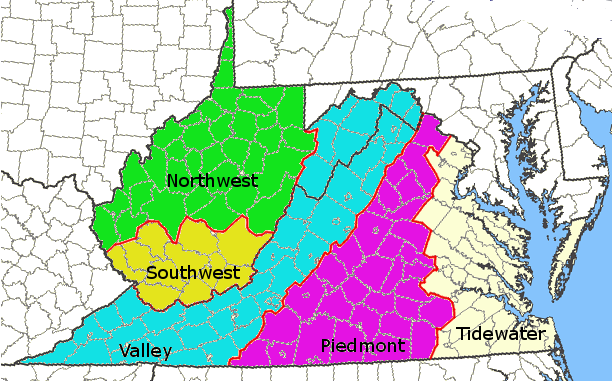

Political conflicts among Tidewater, the Piedmont, Northern Virginia, and however many regions you wish to identify are a long part of the state's history. These differences led to a formal split and the creation of a new state, West Virginia, in 1863.

In the first inauguration speech of a West Virginia Governor, Arthur Boreman made clear why splitting from Virginia was justified:1

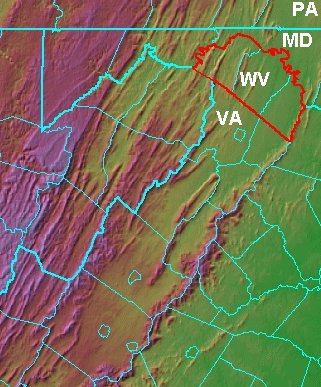

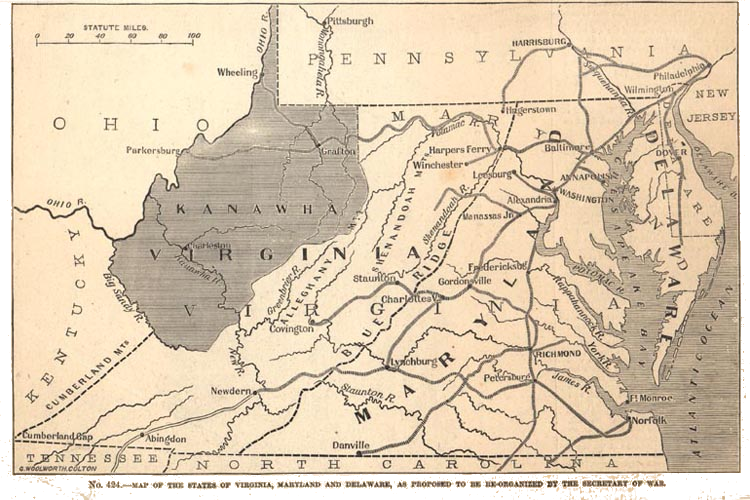

Some boundaries proposed for West Virginia during the Civil War extended much further to the east. The new state could have included all Virginia counties west of the Blue Ridge, and even all the counties along the Potomac River downstream to the Occoquan River. In the end, West Virginia included only three Shenandoah Valley Counties - and the southwestern Virginia counties within the Valley and Ridge province stayed with "old" Virginia, due to the influence of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.

Panhandle of West Virginia showing Morgan,

Berkeley, and Jefferson counties in the Shenandoah Valley

European settlers did not spread out through Virginia after 1607 like ripples from a rock thrown into a pond. Settlement did not expand equally away from a central point at Jamestown, with new farms and communities emerging a few miles in every direction every few years.

The English settled first in Tidewater Virginia, clearing the land near the rivers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Instead of a smooth, gradual spread outward from one central place, English settlement spread primarily to the north of the James and east of the Fall Line. South of the James, in the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound watershed, there was less demand for land in the first 150 years after Jamestown.

Why? South of the Appomattox River watershed, Virginia rivers do not empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Farm crops loaded on boats and shipped downstream end up in North Carolina. Farmers south of the Appomattox River could load boats to carry crops down the Blackwater, Nottoway, or Roanoke rivers - but those boats ended up in the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound, while most ships sailed to Chesapeake Bay ports.

Source: Chesapeake Bay Local Assistance Department

By 1700, a gentry of 5% or so of the population (the "First Families of Virginia" or Cavaliers) took control of the politics and economy of the colony. The plantation owners shifted from importing indentured servants to importing slaves as the primary labor force for their tobacco plantations.

They built large manor houses on their Tidewater plantations - Berkeley, Carter's Grove, Mount Airy, Stratford Hall. Using their influence in the House of Burgesses and with the Governor, they obtained land grants and speculated in western lands - lands west of the Fall Line. The Lees and Carters competed in the upper Potomac watershed for control of the Fairfax land office and access to waterfront property downstream of Great Falls.

Governor Spotswood led a military exploration/real estate speculation expedition up the Rappahannock River valley in 1716. His "Knights of the Golden Horseshoe" crossed the Blue Ridge near where modern US Route 33 passes through Swift Run Gap. The "knights" celebrated their arrival with multiple toasts on the banks of the Shenandoah River, in a party that is still memorable nearly 300 years later:2

Modern real estate agents will recognize the expedition (and the party...) as a familiarization tour to spur land sales. The old saying about real estate values being determined by three things ("location, location, and location") applied in colonial times as well as today. Spotswood himself imported indentured servants to develop an iron plantation at Germanna, upstream from Fredericksburg, while defending his even-handedness in supporting development south of the James.

While the officials in Williamsburg processed requests for grants and occasionally an actual survey for a patent west of the mountains, a few of the gentry actually visited their land claims on the other side of the Blue Ridge. George Washington spent much of the 1750's in Shenandoah Valley and travelled south to Shawsville to inspect frontier forts. Patrick Henry travelled to visit his properties nearby in Christiansburg, a town named after his brother-in-law William Christian.

But most settlement west of the Blue Ridge came from a different direction, *not* from Tidewater Virginia. The House of Burgesses created new counties stretching to the crest of the Blue Ridge (such as Prince William) in the 1730's, but settlers did not spread westward in a steady flow. Instead, lands west of the Blue Ridge were settled by immigrants walking southwest from Philadelphia, before all the lands east of the mountains were fully occupied.

In an agricultural economy, the higher-quality limestone soils of the valley were one reason for bypassing the Blue Ridge. Even today, Virginia's two primary agricultural producers are Augusta and Rockingham counties. Recognizing the uneconomic value of farming in the mountains, Virginia purchased the hard-scrabble farms in the Blue Ridge 70 years ago and donated the land to the Federal government for Shenandoah National Park.

However, another key reason for settling the Shenandoah Valley from the north rather than the east was cultural rather than physical.

The religious intolerance in Europe spurred many refugees to flee to the New World in the first half of the 1700's. Virginia had "established" the Anglican church as an official part of the government. Mandatory church levies (i. e., taxes collected by the sheriff) funded both social welfare and church operations, including the construction of the brick colonial churches still seen in Tidewater today (such as Bruton Parish church in Williamsburg and Pohick Church in Fairfax County).

Tidewater was dominated by the Church of England, the region but was not exclusively Anglican. International shipping ports like Norfolk had numerous non-Anglican sailors adding diversity to the Virginia culture, and the colony was relatively tolerant of Protestant dissenters. Prior to the French and Indian War, Scottish merchants ("factors" purchasing tobacco in Fall Line cities from small planters) provided a Presbyterian business class.

In addition, in the Piedmont a substantial number of indentured servants and poor farmers were stimulated by the "Great Awakening" and itinerant dissident preachers, especially the Baptists. Patrick Henry's mother was a Presbyterian convert, perhaps one reason he was such a rabble-rouser... Historians still debate how the threat to the hegemony (domination) of the gentry class affected the political thinking prior to the American Revolution.

West of the Blue Ridge, the Anglican and Tidewater English presence was far more limited. Immigrants coming south through Pennsylvania were predominantly Protestant - but not Anglican - refugees, people who fled the many conflicts among political states that have now been assembled into modern-day Germany. These Pennsylvania "Dutch" fled to William Penn's haven, the Quaker colony of Pennsylvania. They discovered the price of land was lower as they moved west, and substantially less as they crossed the Potomac River into the "empty" Shenandoah Valley in Virginia.

The valley was empty in part because it was a border territory raided by Iroquois from the north, Cherokee from the south, and Shawnee from the west. In addition, diseases brought from Europe by Spanish explorers in the 1500's and permanent colonists in the 1600's may have dramatically reduced the population of the indigenous Native Americans.

In the days when transportation was by one-horsepower wagon, the Blue Ridge was a significant physical barrier that divided the colony.

"East" Virginia was the Tidewater region, plus the Piedmont region where small planters produced tobacco for export. Those planters rolled hogsheads of tobacco eastward, downhill to the cities like Fredericksburg developing along the Fall Line, in order to ship their crop to Europe. Wagons that carried crops eastward to market returned home with nails, cloth, and other manufactured products. The mercantile system ensured that industries in England would have a market in the colonies, and the Fall Line cities became the "hinge" between the Piedmont and England.3

But those cities were irrelevant to the immigrants west of the Blue Ridge, so long as roads through the mountain gaps were too poor for farm wagons. The immigrants who had come south from Philadelphia, migrating west to Lancaster and then following the limestone valleys south into Virginia, sent their farm products back north as well. Since the roads were poor (OK, really really poor), hauling tobacco to Philadelphia was a poor (OK, really really poor...) economic decision.

So the immigrants in the valley raised livestock, walking their herds to market in Baltimore and Philadelphia long before cattle drives of Texas longhorns captured Hollywood's imagination. If the movie moguls ever film a Virginia cattle drive, look for the herds of cattle from the South Branch of the Potomac River walking north, down the Shenandoah Valley. After numerous pauses for grazing on grasslands in the valley, the herds should cross the Potomac River and then veer eastward to the market cities of Maryland and Pennsylvania. Expect the herd of cattle to be followed by droves of pigs, feeding on the manure left behind on the trail by the cattle - with a flock of turkeys or chickens behind the pigs, fully utilizing all the food resources on the way to market.

Prior to the French and Indian War, the economic ties, religious sympathies, and family loyalties of the Shenandoah settlers were to the north, not towards Tidewater Virginia. However, after the Piedmont filled with settlers oriented to the Tidewater, a substantial number of "English" immigrants came into the valley across the Blue Ridge.

The French and Indian War triggered a decade of Tidewater commitment to the valley, from 1753-1763. George Washington lived in Winchester for several years as the commander of the Virginia forces, and the legislature and the governor committed substantial resources (though still far-from-enough) to fund forts and militia on the frontier from the Potomac to the New River. He was sensitized to the western attitudes and sought throughout his political career to use transportation improvements to link western loyalties to the primary American cities on the East Coast.

However, by 1785 those living on the western edge of the state were agitating for creation of a separate state. James Madison thought Col. Arthur Campbell was the primary source of petitions to the General Assembly calling for amending the state constitution adopted in 1776 or splitting Virginia.

By the 1800's, roads crossed from Tidewater through the "wind gaps" in the Blue Ridge to the Valley. In the 1850's, railroads such as the Manassas Gap Railroad cemented the economic ties between the valley and the Fall Line cities.

But transportation improvements were never fairly allocated to the western counties of Virginia. After the Board of Public Works was created in 1816, the state financed 40-60% of the cost for turnpikes, plank roads, canals, and railroads. The legislature approved few projects west of the Allegheny Front, where the waters drained into the Ohio River.

Instead, the Tidewater-dominated General Assembly supported projects to enhance farm-to-market transportation leading to Petersburg, Richmond, and Fredericksburg. (Alexandria was part of the District of Columbia from 1800-1846, and the State of Virginia was reluctant to finance improvements to a non-Virginia city during those years.)

And the western counties were grossly under-represented in the General Assembly. In 1816, disgruntled political leaders organized the Staunton Convention with representatives from 36 counties, including some from the eastern region of Virginia. The convention noted that only 1/3 of the white population lived east of the Blue Ridge, but that minority controlled the majority of seats in the House of Delegates and had even more power in the State Senate.4

The number of white males west of the Blue Ridge was greater than the equivalent population east of the mountains, when the state constitution was revised in the early 1850's. But the constitution was written so the western counties would never achieve control of the State Senate.

Tidewater planters were concerned that western voters would change the tax structure to finance "internal improvements." The Tidewater planters ensured property taxes on slaves remained low, while taxes on land were relatively high. The western residents had most of their investments in land while the eastern planters had invested in slaves. Instead of ensuring the tax burden was fair, the western residents were taxed more heavily - and the taxes were used to finance transportation improvements in the eastern portion of the state.

There was ill will between the regions of Virginia before the Civil War. Northern Virginians benefitted when Whigs controlled the General Assembly, supporting internal improvements in the Potomac watershed such as the C&O canal. Democrats steered investments to the James River watershed when they controlled the political machinery. But westerners never got their fair share... no matter which party was in control before the Civil War.

After the 1776 state constitution was revised for the first time in 1830, the Tidewater planters provided a higher level of public support for residents west of the Blue Ridge. The Board of Public Works provided financing for turnpikes, canals, and railroads linking the southern ("upper") Shenandoah Valley near Staunton to Richmond, and the more-northern portion of the valley near Front Royal/Mount Jackson to Alexandria.

As one study of the origins of West Virginia has noted:5

Three conventions in western Virginia agitated for the General Assembly to expand the political power of those living west of the Blue Ridge, but failed to make major revisions. The 1830 constitution did not extend suffrage to all white men, reducing the influence of the "freeholders" working on farms owned by others in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province. Election districts were drawn so the counties west of the mountains could elect only a minority of the General Assembly members. The ratio of the east-of-the-Blue-Ridge members vs. west-of-the-Blue-Ridge members was frozen, no matter how population was calculated after a future census.6

By 1850, the legislature had created 19 additional counties west of the Blue Ridge. A new state constitution that year eliminated the requirement of voters to own a certain amount of property, increasing the number of white men west of the mountains who could vote. However, Eastern legislators maintained their dominance over the legislature when drawing the boundaries of election districts. The districts west of the Blue Ridge elected 66 seats in the 152-member House of Delegates, ensuring that westerners would control no more than 43% of that house. In the 50-member State Senate, 19 seats (38%) were allocated to districts west of the Blue Ridge.7

The regional dispute was centered on unbalanced taxation and investment. Westerners resented how Eastern Virginia slaveowners used their political power to limit taxes on "slave property," but that objection was not the same as opposition to the institution of slavery. The majority of white landowners in the western counties, including those who owned no slaves, were not advocates of emancipating the enslaved people.

As the Washington Post noted in 2020, when West Virginia legislators invited Virginia counties to split from Virginia and become part of West Virginia during a political uproar over legislation affecting guns:8

When Virginia's Secession Convention finally voted to leave the Union in April 1861, the representatives of the western counties chose to meet separately and to "secede" from Virginia. This political decision was the final break, creating a fixed political boundary between two separate states after West Virginia was accepted into the Union. What had been a shifting frontier between Virginians who were oriented towards the Chesapeake Bay vs. the Mississippi drainage was locked into place.

In 1862, Governor Pierpont of the Restored Government of Virginia described why the western and eastern sections of the state had developed very different cultures:9

Despite the tilt towards Tidewater, the southwestern counties west of the Blue Ridge stayed in Virginia and did not join West Virginia in 1863-66. A decade before the Civil War, the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad crosed the Blue Ridge. The rail line was built west from Lynchburg through the Roanoke River gap, then down the Valley and Ridge to Bristol.

The easy transportation link to the Fall Line ports transformed the economy of southwestern Virginia. While the percentage of slaveowners in the region remained low compared to the portion of Virginia east of the Blue Ridge, the economic links between the southwest and the eastern part of the state grew substantially.

in 1860, the Trans-Allegheny District of western Virginia was divided into Northwest and Southwest districts

Map Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas

Counties west of the Allegheny Front seceded from Virginia starting in 1861, and established a new capital in Wheeling for the new State of West Virginia in 1863. However, the far southwestern counties retained their loyalty to the capital based in Richmond, due to economic and cultural ties that had been strengthened through business facilitated by the rail line.

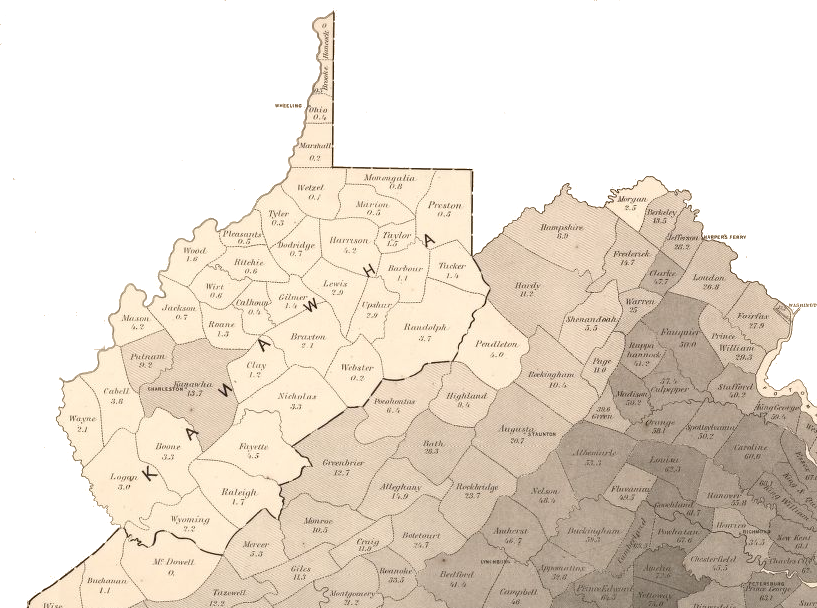

The Federal government anticipated the outbreak of a civil war that might trigger the western counties in Virginia to splinter off and form a separate state. The United States Coast Survey obtained early access to the 1860 Census data, and created the first map displaying that data in June, 1861. By September, a new version of the map displayed the name of the proposed new state - Kanawha.10

the percentage of population held in slavery was lower in the 39 original counties proposed for the State of Kanawha - though McDowell County was excluded

Map Source: Library of Congress, Map of Virginia : showing the distribution of its slave population from the census of 1860 (September, 1861)

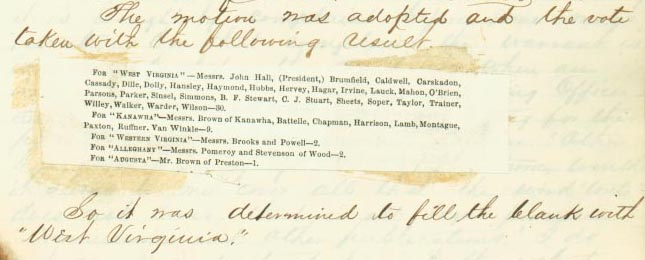

On December 3, 1861, the First Constitutional Convention in Wheeling started debate with:11

The subsequent debate included expressions of reverence for supposedly-virgin Queen Elizabeth; concerns over confusions if the name "Kanawha" was used for both a county and the entire state; suggestions for "Allegheny/Alleghany," "Potomac," and "Augusta;" support for "Columbia," "Western Virginia," and "New Virginia;" and opposition to any use of "Virginia" in the name. One member of the convention drew laughter when he suggested it would be unfair to use "Virginia" in the name of the new state:12

The debate concluded by striking out "Kanawha" from "The State of Kanawha shall be and remain one of the United States of America... and inserting a blank, then voting on how to fill the blank in "The State of ______ shall be and remain one of the United States of America..."

The first vote was to choose the name "West Virginia" to fill the blank. When 30 of the 44 members voting endorsed that option, debate ended and the name of the new state had been decided.13

West Virginia was chosen over Kanawha, Allegheny, and New Virginia, among other choices

Source: West Virginia Division of Culture and History, "What's In A Name?" The Naming of West Virginia

West Virginia could have been much smaller...

Source: West Virginia Public Broadcasting, April 17, 1861: Virginia Politicians Vote to Secede from the Union