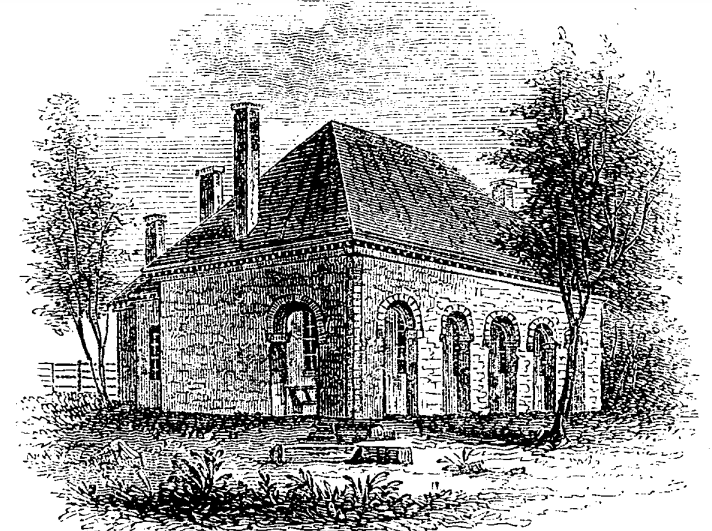

building Yeocomico Church with brick rather than less-expensive wood demonstrated permanence and authority of the Church of England

Source: Library of Congress, Yeocomico Church, Cople Parish, Hague vicinity, Westmoreland County, Virginia

building Yeocomico Church with brick rather than less-expensive wood demonstrated permanence and authority of the Church of England

Source: Library of Congress, Yeocomico Church, Cople Parish, Hague vicinity, Westmoreland County, Virginia

In the 1500's, Kings and Queens in England sought to force subjects to follow their personal perspectives on religion, especially how religion confers authority on rulers. Henry VIII declared that he, rather than the Pope who led the Roman Catholic church from Rome, had the top authority over religious theology and doctrine to be practiced in England.

In the 1534 Act of Supremacy, Henry VIII had Parliament define the King as the head of the Church of England. Using that authority, Henry VIII later confiscated the lands and wealth of the monasteries which had controlled 20% of England's cultivated land.

Henry personally had been raised as a Catholic, and he was comfortable with those beliefs and rituals. His dispute with the Pope revolved around his desire to divorce his first wife and the Pope's refusal to authorize the divorce. Henry VIII did not accept salvation by faith alone, as espoused by Martin Luther. Henry VIII became the leader of a Church of England that was, organizationally, separate from the Roman Catholic church, but Henry VIII still retained traditional Catholic doctrine for controversial issues such as transubstantiation and clerical celibacy.

In contrast, his son Edward VI was raised as a Protestant - and who would follow him was a problem for the Protestant leaders in England. His half-sister Mary had ben designated in Henry VIII's will as next in line to inherit the throne after Edward VI. However, Mary was a Catholic. Her mother, Henry VII's first wife, was Catherine of Aragon - daughter of the King of Spain, and a strong supporter of the Pope's authority.

Edward sought to change the line of succession. He wanted to have a Protestant cousin replace him, but that effort failed. Lady Jane Grey was quickly displaced after Edward VI died and his half-sister Mary took the throne.

Queen Mary re-established Roman Catholicism as the state religion, and enforced that decision. She became known as "Bloody Mary" for the execution of people whom she categorized as heretics, including 300 people burned at the stake. In the 1500's, religious uniformity was equivalent to political uniformity. Religious dissenters were perceived as a threat to the ruler's control.

In 1554, Queen Mary married the man who became King Philip II of Spain. That marriage could have led to a partnership with Spain regarding the religious wars in Europe, with England intervening on the Catholic side. In international relationships, the religion of the rulers was a significant factor in determining friend vs. foe.

Mary died childless in 1558, and her half-sister Elizabeth succeeded her. Elizabeth I was a Protestant, and Spain sought to gain control over England by a military conquest. The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 reduced the threat, but England's political leaders still viewed Catholics as potential traitors.

One threat was Mary Queen of Scots, a descendant of Henry VII of England. She was the only legitimate heir of King James V of Scotland, and Henry VIII had tried to force a marriage between her and his son Edward. Despite a war with Scotland called the "rough wooing," her father sent her to Catholic France. There she married the prince. He died before becoming king, so she returned to Scotland. She became Queen Mary, was imprisoned by the Protestant nobles, and escaped to England in 1568.

Though kept under house arrest or imprisoned while in England, she conspired with other Catholics to seize power from Queen Elizabeth I. After enough evidence was collected to prove her guilt, Protestant Queen Elizabeth order the execution of Catholic Queen Mary in 1587.

Elizabeth I, the "Virgin Queen," also died childless in 1603. Her successor was James VI of Scotland, the son of Mary Queen of Scots. He had been baptized as a Catholic, then raised a Protestant, and eventually married a Catholic.1

James I was inclined to tolerate openly the different religious practices of both Protestants and Catholics. He authorized a new translation of the Bible for better understanding of it by those who could read, a translation which became the King James's Version. James' tolerance cooled after the 1605 Gunpowder Plot was foiled. Guy Fawkes and other Roman Catholic conspirators failed in their plan to blow up Parliament, and the Catholic threat created a greater focus on religious conformity in order to minimize political dissent.2

The restrictive approach of James I was demonstrated in 1606, when venture capitalists sought royal authority to establish a colony in the New World. His First Charter, issued April 10, 1606, did not require religious conformity. However, on November James I issued Articles, Institutions and Orders that required the London Company to establish the Church of England as the one true faith in the new colony:3

In its first meeting in 1619, the General Assembly formalized the establishment of the Church of England, also known as the Anglican Church, as the only authorized religion in the colony. The Church of England became the official ("established") government-protected religion of Virginia in 1619. The burgesses in 1619 passed a law requiring that:4

in the colonial period, ministers in Anglican churches spoke down to parishioners who sat in pews ranked by social status

Source: Library of Congress, Pohick Episcopal Church, Lorton vicinity, Fairfax County, Virginia. Interior

England was not a theocracy where the church controlled the government. It was the reverse, where the government controlled the church and appointed the bishops. In Europe, there were constant challenges regarding the temporal authority of the Pope in Rome vs. the power of monarchs in separate nations.

The Catholic kings in Spain tried to force neighboring countries with Protestant rulers to become Catholic and acknowledge the Pope's authority. Those religious wars may have been based in part of efforts to guide spirituality. More likely, the primary driver was the desire of a ruler to exert earthly power more than to ensure the people in another nation achieved eternal salvation.

When a king died, a new one could claim under the divine right of kings that they had the power to establish a different official religion for the nation. That power to define the nation's faith ("cuius regio, eius religio") was affirmed in the 1555 Peace of Augsburg.

Though a European monarch had the authority to impose his personal ideology, not all chose to force a country to fit their personal perspective. Henry IV of France recognized that his conversion from a Protestant, becoming a Catholic, would solidify his ability to rule France and supposedly said:5

The alliance of church authority and state power in England was useful to both institutions. By establishing just one official church, the monarch limited competition from non-Anglican preachers. Like the Pope, English bishops claimed they derived power straight from Jesus through apostolic succession. When the Archbishop of Canterbury placed a crown on the heads of English monarchs, those sitting on the throne benefitted from legitimacy granted by the Church of England.

All of Virginia's governors and all members of the Governors Council were Anglicans in the colonial period. All but one member of the House of Burgesses were Anglicans between 1619-1776.

Churches were powerful institutions for reasons other than religious belief. Sermons were a primary source of information in Virginia's colonial era. An adult who attended church every Sunday might hear about 15,000 hours of sermons during their lifetime. In four years at college, a modern student might hear only 1,500 hours of lectures. As one scholar has noted:6

Oher colonies also sought to establish religious conformity. Separatists Pilgrims and then Puritans came to Massachusetts to escape control of the Church of England, but not to create religious freedom for faiths and worship practices other than their own orthodoxy. Puritans leaders punished nonconformists and created a state-imposed religion even more rigid than Virginia.

At different times, the governors of Virginia practiced official discrimination against dissenters. Puritans came to Virginia, but the royal governors did not encourage them to stay. Governor William Berkeley forced 300 Puritans to flee to Maryland in 1649. Dissent in faith was conflated with dissent against the legitimacy of Charles I as king, so Catholics, Puritans and Quakers were chased out of the colony. Virginians also tried to force the Catholic Calvert family out of power in Maryland during Ingle's Rebellion in 1646.

The General Assembly sought to keep Catholics who believed in papal authority and transubstantiation from settling in the colony. It imposed Anglican liturgy, sacraments, and other practices to create:7

Religious differences were a key part of the English Civil War, culminating in the victory of the Parliamentary army and execution of King Charles I in 1649. Virginia stayed loyal to the king, earning the nickname "The Old Dominion," until Puritan forces arrived and displaced Gov. William Berkeley.

Puritan governors allowed Virginians to continue to use the Book of Common Prayer that had been banned in England. However, prayers for the king had to be eliminated.

Charles II, Protestant son of Charles I, was restored to the throne in 1660. In Virginia, the General Assembly passed new laws that imposed religious conformity, clarified the responsibilities of the vestry, and officially established the size of the vestry at 12 men to manage each parish.

The new laws also mandated weekly attendance at church, where sermons were an effective way to shape attitudes of the parishioners. Other than conversations with neighbors and county court sessions, there were few other sources of news or opinion in colonial Virginia at the time. The first newspaper was not published in Virginia until 1736. In 1661, Gov. William Berkely highlighted the advantage of having control over information:8

Those who failed to attend church services could be fined. That provision was designed to pressure the few Quakers in Virginia to leave. It also created a selective enforcement mechanism to force people who upset local leaders in various ways, such as by spreading malicious gossip, to modify their behavior:9

St. Luke's Church in Isle of Wight County, originally known as Newport Parish Church, was built near the end of the 17th century

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 081-0066 Timber Ridge Presbyterian Church (by Elizabeth Lipford/DHR, 2022)

Failing to at least pretend to be Anglican, and violating the standards established for identifying as an Anglican, could have significant consequences. Those who refused to have their children baptized could be fined in local county courts. The General Assembly ensured the parish vestries and county courts had the economic and legal resources to impose the beliefs of the Virginia gentry on all colonists:10

James II replaced Charles II after he died in 1685, and the crown shifted back to a Catholic. James II sought to legitimize Catholic religious practices and enable Catholics to serve in public offices. To accomplish that goal, he sought the support of the 15-20% of people in England who did not identify as Anglican, including Presbyterians and other Protestant dissenters as well as the Catholics.

In 1687, James II officially issued a "Declaration of Indulgence" that granted religious freedom to Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Unitarians, and other dissenters in England. They were no longer forced to speak the "Oaths of Supremacy and Allegiance" that had been required to hold civil and military offices, and were no longer subject to being fined for failure to attend Anglican church services.

In 1688, during a brief window of tolerance, George Brent became the only Catholic elected to the Virginia General Assembly during the colonial period. He served for one session, until King William and Queen Mary replaced King James II.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 forced King James II out of power. English members of Parliament recruited King William and Queen Mary from the Netherlands to replace James II because they were Protestant rulers.

Under William and Mary, in 1689 Parliament did pass the Act of Toleration, officially titled "An Act for Exempting their Majestyes Protestant Subjects dissenting from the Church of England from the Penalties of certaine Lawes." Worship by non-Anglican Christians such as Presbyterians and Baptists remained acceptable under William and Mary, but only Protestant faiths were tolerated. Catholic priests were banned.

In colonial Virginia, religious toleration was limited. A 1699 law passed by the General Assembly authorized fining someone who did not attend a church at least once every two months unless they had an excuse accepted by the county court. Dissenters were exempted under the Act of Toleration, but only if they had gone to their own house of worship within the two month period. Attending church - some sort of Protestant church - was mandatory.

Under the Act of Toleration, Virginia's General Court in Williamsburg began to issue a license for non-Anglican Christian ministers to preach and organize churches. The license authorized preaching only in a fixed location, constraining the non-Anglicans who were itinerant preachers traveling constantly in the less-settled backcountry.

Ministers in the backcountry, where the Anglican church was least significant, were burdened by the requirement to travel to Williamsburg to get a license. Many of the Separate Baptists refused to apply for a license, claiming the civil government had no right to determine who was entitled to preach the word of God in a religious setting.

Licensing based on the 1689 Act of Toleration proceeded slowly:11

In the 1700's, immigrants from Scotland, Ireland, and Europe brought people with different religious beliefs to the colony, including German Pietist faiths, Lutherans, and Presbyterians. In the Great Awakening during the 1730s and 1740s, the number of dissidents expanded as religious fervor and more-emotional worship services than Anglican preaching increased in popularity. New religious practices were adopted, such as full-immersion baptism and the "laying on" of hands. Diversity of religious ritual and adoption of new styles of worship threatened the traditional social order in which acceptable behavior was determined by the gentry.

Other colonies had been more flexible on permitting different religious activities. The Calverts in Maryland had long recognized that toleration of non-Catholics was essential for attracting new colonists. That colony had passed "An Act Concerning Religion," also known as the Maryland Toleration Act, in 1649. When Virginia expelled Puritan preachers, Maryland welcomed them. From its start, William Penn's Pennsylvania colony was the most successful in attracting people with various Protestant beliefs.

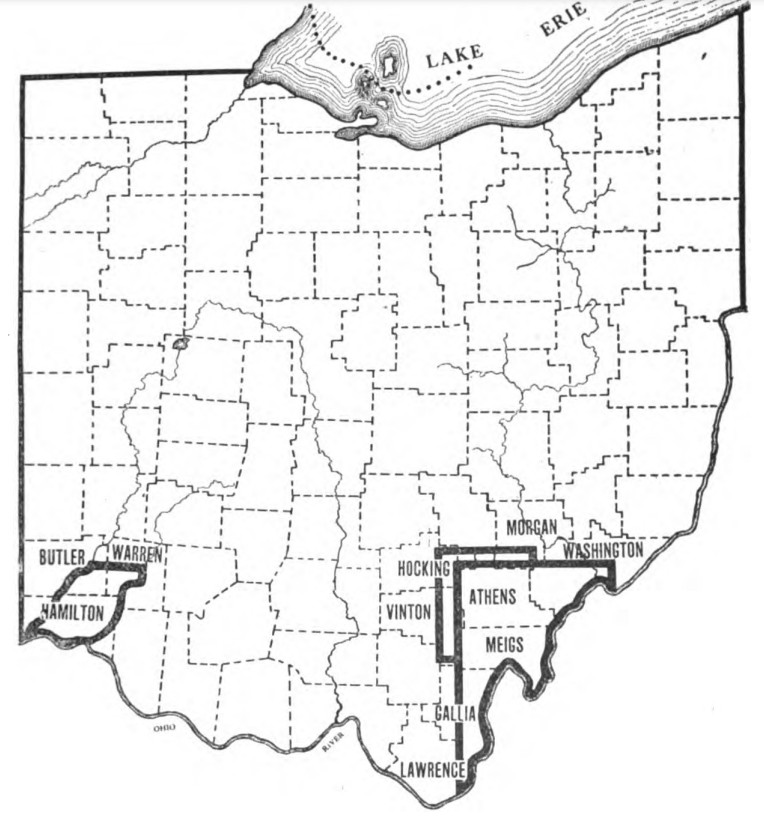

Virginia's political leaders first embraced religious diversity in the 1720's. That decision was based on geopolitical considerations, rather than greater toleration or acceptance of other faiths.

Governor Spotswood saw the advantage in welcoming immigrants that had come from Ireland and modern-day Germany to Pennsylvania. Those immigrants desired to settle on cheaper land in the Shenandoah Valley, but were unwilling to become Anglicans. The dissidents were valued because new Protestant settlers on the western border would provide a buffer against raids by the French moving into the Ohio River Valley. The new colonists would also be a barrier against raids by Native Americans who were being displaced. The governor accepted that the Scotch-Irish and the "Pennsylvania Dutch" would worship and organize churches in ways different from the Anglicans.

Governor Gooch followed Spotswood's policy. Starting in 1730, Governor Gooch granted John and Isaac Van Meter 40,000 acres near Cedar Creek, Opequon Creek, and the Shenandoah River in order to attract more settlers, even though they would be non-Anglicans walking south from Pennsylvania.

On the eastern side of the colony at this time, settlers were finally beginning to fill up the Tidewater region but few had chosen to start farms west of the Fall Line in the Piedmont physiographic province. There were enough people in Stafford County in 1731 to justify splitting it and creating Prince William County, which initially included the land now within Fauquier, Loudoun, and Fairfax counties.

When colonial officials in Williamsburg issued large grants of land that was within the boundaries of the Fairfax Grant, Lord Fairfax decided to survey and establish his claim. The Van Meter brothers avoided getting trapped in what became an 80-year dispute over who had the authority to sell land in the Shenandoah Valley; they sold their claims quickly to Joist Hite.

Hite recruited his buyers from recent immigrants in Pennsylvania, as did others who got large grants of land west of the Blue Ridge. Quakers from Hopewell in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania migrated across the Potomac River and settled on land that had been granted to a Quaker (Alexander Ross) and a Presbyterian (Morgan Bryan). Those Pennsylvanians founded the Hopewell Meeting and built a log meetinghouse in 1734. It burned in 1757, and the Quakers built the first half of the current limestone meetinghouse between 1759-1761.12

the plain and functional Hopewell Meetinghouse is the oldest house of worship in Frederick County

Source: Library of Congress, Quaker Meeting House, Winchester vic., Frederick County, Virginia

In 1732, Col. William Beverly obtained a grant further south in an area already known as the Irish Tract. He recruited more Scotch-Irish to purchase parcels within Beverly Manor and organized a town named after Governor Gooch's wife, Lady Staunton. In 1739 a Quaker from New Jersey (Benjamin Borden) got a large grant to the south of Beverly Manor, in what now is Rockbridge County.

Beverly partnered with Irish ship captain James Patton. He brought immigrants directly from Ireland up the Potomac River, and then walked them west across the Blue Ridge into the Shenandoah Valley. Patton later got his own grant on the New River. He populated Dunkard's Bottom, now flooded by Claytor Lake, with Anabaptists known as "Dunkers" (similar to Mennonites and Amish, and named for the practice of full-immersion adult baptism) from the German Pietist community in Ephrata, Pennsylvania.

Timber Ridge Presbyterian Church in Rockbridge County, built in 1755, is the second oldest Presbyterian house of worship in the Shenandoah Valley

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 081-0066 Timber Ridge Presbyterian Church (by Calder Loth, 2017)

East of the Blue Ridge in Hanover County, in 1743 "ordinary" people led by a bricklayer began reading religious tracts on their own and were inspired by George Whitefield's revivals. They developed different interpretations than what was preached by government-paid Anglican ministers.

Religious dissidents started holding their own meetings, independent from the Sunday services led by the Anglican minister of the parish. Some dissidents were fined by the county courts for failing to attend Anglican church services, but the community of dissidents expanded in Hanover County and finally recruited a Presbyterian minister from Southwest Virginia to preach.

Rev. Samuel Davies first came to Hanover County in 1747. In 1752, he obtained an official opinion from the attorney general in England that William and Mary's Act of Toleration did apply to the colony of Virginia, as well as in England. That decision affirmed the legal right of Presbyterians to preach and for meetinghouses of dissenters (the alternative to attending Anglican churches) to be authorized. However, dissenters listening to Davies and other Presbyterian ministers were still required to pay the county taxes that funded operations of the Anglican parishes and paid salaries for Anglican ministers.

When Anglicans in a community felt threatened by the growth of the "New Light" Presbyterians, the county court had the legal authority to limit activities of the dissenters. In 1758, the Lancaster County court revoked a license which it had issued "unadvisedly" for a Presbyterian meetinghouse.

The slave-owning elite used the power of local government to limit missionary work by dissidents within the enslaved population. In a radical break from Anglican tradition, Baptists worshipped in mixed-race congregations, baptized free and enslaved blacks, and allowed women to have leadership roles. New religious beliefs that led to overt violation of social norms, especially the crossing of racial boundaries, threatened the traditional political power structure within the colony as much as the potential of a French army marching southeast from the Ohio River.

The Separate Baptists did not require that their preachers be ordained or educated; those who felt the call to preach were welcomed by a gathering. In contrast to the Church of England, which struggled to fill pulpits in different churches with "qualified" ministers who had an appropriate social background, dissident groups did not suffer a serious shortage of preachers.

The gentry's prejudice against Presbyterians moderated after the Baptists emerged; Anglicans began to view the Presbyterians as a less-threatening group. Expansion of the Separate Baptists in Virginia began in the 1750's, at the same time the colony needed to recruit troops for the French and Indian War. Local militia leaders, typically also close allies or even members of the Anglican vestry, had to ameliorate their prejudice against Presbyterians and Baptists in order to recruit soldiers to join the Virginia Regiment of Provincial Regulars that George Washington led.

Growth of religious dissidents was facilitated by support from "outside agitators:"13

Though still practicing as ministers of the Church of England until 1784, Methodists ministers began to split the established church after Robert Williams arrived in 1772. Methodist preachers did not defend slavery, in contrast to the interpretation of the Bible offered by traditional Church of England (Anglican) ministers.

The Great Awakening in the mid-1700's increased the importance of religion in public life, but spurred more Virginians to break with Anglican traditions and chose their own leaders without endorsement by the parish vestry. As worship rituals and theology became a personal choice, the role of the established church was minimized.

Authority in colonial Virginia was exerted through "soft power." How the elite dressed, the architecture of their mansions, and seating arrangements in church defined who was powerful and could command obedience.

County sheriffs had the power of arrest. However, in contrast to today, during colonial times there was no police force routinely on patrol enforcing a thick book of laws governing behavior. Informal rules of behavior, rather than formal laws and regulations, shaped how people acted. Other than slave patrols there was no equivalent to the modern practice of selective police enforcement routinely targeting minority groups, such as traffic laws.

People complied with colonial laws and social norms out of tradition and respect for the wealthy elite. That pattern of behavior was reinforced in Anglican churches every week. During the 1700's there was a fundamental assumption that colonial Virginia should be a hierarchical society, with a tiny top class of wealthy and powerful people and a large bottom class of enslaved people defined by skin color. Behavior of the enslaved was controlled by force when necessary. Behavior of white colonists was controlled by custom, with weekly sermons by Anglican ministers justifying the social structure.

The emergence of alternatives to the Church of England created new centers of authority. Diversity threatened the traditional hierarchy. As Presbyterians and Baptists attracted more followers, lower respect for men serving on the Anglican vestry reduced the informal authority exerted by elite families over the white population.

the architecture of Christ Church in Alexandria was intended to convey power and strength

Source: Library of Congress, Christ Church, Alexandria, Virginia

Finding qualified Anglican ministers to fill the pulpit in every parish was always challenge. It was difficult to recruit the best and brightest Anglican ministers to the colonies from England. Even poorly-trained Anglican ministers ordained on the eastern side of the Atlantic Ocean could find a better job in England.

Part of the recruitment problem was that ministers were not automatically held in high respect by the congregation or the vestry that ran a parish in colonial Virginia. Upper class Virginians did not view serving as a minister as an honorable profession, and discouraged their children from taking such positions. Many ministers in Virginia parishes came from Scotland and Ireland, and were viewed as coming from a "lower class" than the members of the vestry. The behavior of some Anglican ministers involving alcohol and sex was inconsistent with the moral teachings in the Bible, further undercutting the reputation of ministers.

The failure to send an Anglican bishop to Virginia who could ordain ministers in Williamsburg limited the organization, discipline, and political independence of the established church. The Bishop of London sent a Commissary to oversee the work of the Church of England.

The most influential Commissary was James Blair, who served from his appointment in 1689 until his death in 1743. He arranged for the founding of the College of William and Mary in 1693, and arranged for ministers to be appointed whenever there was a vacancy in a parish. The glebe of the Henrico Parish served by Rev. Blair was Varina Plantation. He lived there between 1685 and 1694.

Varina Plantation was also the Henrico County seat, the location of the local courthouse, for 120 years between the founding of the county in 1632 until 1752. However, the story that it was the home of Pocahontas and John Rolfe is unverified. Henrico County purchased the 2,095-acre plantation in 2024 to preserve the historical site and its open space.

Some ministers preferred having the presiding bishop living on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, and just a Commissary in Williamsburg with limited disciplinary powers. In 1661, the General Assembly had required that only ministers who had received ordination from "some Bishopp in England" could preach in Virginia.

Anglican ministers were thought to be empowered in the apostolic succession from Jesus through the laying-on of the hands of a bishop. Vestries later had the option of hiring ministers who had not received ordination directly from a bishop, but such ministers lacked a clear claim to apostolic succession.

Bruton Parish Church was the center of religious activity for government officials when Williamsburg was the colonial capital of Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Bruton Parish Church, Williamsburg, Virginia

Whatever their qualifications beyond public speaking skills sufficient to stir a crowd in a pub or a church, Anglican ministers traveled from England to Virginia with realistic expectations of having a job. An ordained Anglican minister, even one with low personal character and minimal theological training, recognized that some Virginia parish would have a vestry that could not afford to be very selective.

Anglican church operations were funded completely by the taxes imposed by the local parish vestry. Wealthy Virginia landowners controlled the vestries in each parish, so the landowning elite determined how much they would tax themselves. in particular, the vestry composed the timing of the extra tax burden required to build new churches or "chapels of ease" in the periphery of the parish. The extra burden would be most acceptable after years in which tobacco prices and crops had generated a good income.

Ministers were guaranteed a salary while serving a parish, and had some personal income from farming operations on the parish glebe. Vestries were careful before making a long-term commitment to support a minister. They ensured the minister would not threaten the authority of the local wealthy landowners before giving the minister the equivalent of tenure.

Many vestries avoided having their minister "inducted" by the Commissary or Governor, a process which essentially granted them a permanent job unless caught in serious misbehavior. Instead, vestries hired ministers using essentially year-to-year contracts. A dissatisfied vestry could choose to tell a minister that his contract was ending, even though recruiting a new minister would be a challenge.

One vestry in Richmond County tried to fire the minister in 1749 after the dominant landowner, Landon Carter, developed a person prejudice against him. The church door was nailed shut to exclude the minister from the building, and tenants on his glebe lands diverted products from the minister's livestock. The minister responded by filing a lawsuit against the tenants and not the vestry, and he won damages in the county court.

The General Assembly responded to that scandal by giving all Anglican ministers the equivalent of tenure without requiring formal induction in Williamsburg. However, the increased financial security did not translate into increased social status for ministers. The Richmond County case exacerbated the division between the elites in the vestries and the members of the parish vs. the ministers in the pulpits. Support for the established church diminished as ministers became perceived as mere employees, reduced to suing their employers for payment of wages.14

The Parson's Cause case in Hanover County highlighted that the general public's perception of ministers was comparable to the gentry's lack of deference to ministers.

Vestries paid their ministers in tobacco rather than in cash, since specie was rare in the colony. Since 1749 the pay of ministers had been fixed by the General Assembly at 16,000 pounds of tobacco per year, plus income from glebes.

while the Virginia economy was disrupted by the French and Indian War, the price of tobacco climbed during a severe drought in 1755. The shortage of the crop led to a sudden 300% increase in the value of tobacco, from two pence per pound to six pence per pound.

The General Assembly, in which no minister served, responded to the inflated price of tobacco by passing a Two-Penny Act in 1755. After another season of bad weather in 1758, the General Assembly passed another Two Penny Act in 1758. Both laws were short-term responses to the tobacco shortage, and expired after one year.

The laws authorized vestries to pay ministers according to the normal price of tobacco, two pennies per pound - not the temporary inflated value 300% higher. In 1758, the ministers expected to sell their tobacco and collect £450 rather than the usual £150. Tripling of their salary was an opportunity to become wealthy enough to raise their social status and increase clerical independence.

In response to the 1758 bill preventing a salary windfall, one minister expressed openly his hostility towards the legislators:15

The dispute over pay evolved into a dispute over authority in the colony. Half the Anglican ministers in the colony assembled in a convention and sent Reverend John Camm of York County to London. His goal was to get the 1758 Two-Penny Act disallowed.

Acting as the lobbyist of the clerics, Camm argued that the General Assembly's law challenged royal supremacy, and claimed that the House of Burgesses was acting treasonously. Once the ministers sent an official representative to get officials in London to overturn the Two-Penny Act passed in Williamsburg, the colony's political leadership faced a direct challenge to their authority.

The Privy Council did overrule the 1758 Two Penny Act, but did not state if the decision was retroactive. To collect "back pay," three ministers filed lawsuits in 1762-63. They asked the county courts in Virginia to force their vestries to pay the difference between the market value vs. the fixed price of 16,000 pounds of tobacco, for those years when the law was in effect.

Rev. Alexander White filed a lawsuit in King William County, and Rev. Thomas Warrington sued in Elizabeth City County. The jury in King William County ruled against Rev. Alexander White. The justices in Elizabeth City County dismissed Rev. Thomas Warrington's case, after the jury returned an open verdict.

Rev. James Maury's lawsuit was heard by the court in Hanover County, not where he was serving in Louisa County. Rev. James Maury won his case, triggering a second phase of the trial in which the jury had to determine how much money Rev. Maury would be awarded as damages.

Patrick Henry argued the Parson's Cause in Hanover Court House, where his father was the presiding judge

Source: Benson Lossing, The pictorial field-book of the revolution (Volume 2, p.429)

Rev. Maury was surprised to discover that the sheriff did not assemble a jury of gentlemen who would be deferential to a Church of England minister that the local vestry had chosen. Instead, in Maury's terms, the sheriff "went among the vulgar herd." Among those seated in the jury box were several New Light dissenters.

Patrick Henry was the vestry's defense lawyer during the sentencing phase of the "Parson's Cause" case. He made a powerful speech that conflated the power of the clergy and the British government, painting them both as oppressive burdens on Virginia society. Some thought Henry had crossed the line and advocated for treason.

The Hanover County jury awarded Rev. Maury just one penny in compensation, not the anticipated £300. The token damage award reflected both the effectiveness of Patrick Henry's oratory and the low support for Anglican ministers among the "vulgar herd." The jury's verdict also reflected the emerging resistance in Virginia against the authority of the British Parliament and King George III, which Patrick Henry inflamed in 1765 with his speeches against the Stamp Act.16

Source: Historic St. John's Church, The Story of the Parson's Cause with John Tucker

The Anglican clergy's attempt to use county government power to increase their pay backfired. Lawsuits by ministers in county courts, trying to force the local taxpayers to provide funding after failing to obtain local support from the parishioners, helped to poison the close relationship between civil leaders within the Virginia gentry and the Church of England. In the 1760's and 1770's, while challenging the local political authority in Virginia, Anglican ministers preached about the requirement to support distant political authority in London. Not surprisingly, the colonial gentry who controlled county courts and the General Assembly did not view those ministers as allies.

In the first official meeting of the General Assembly in 1776, after the Fifth Virginia Convention had declared independence, the legislators of the new Commonwealth of Virginia eliminated the mandatory taxpayer support for minister salaries. That left the ministers dependent upon donations and income from glebes, without a guarantee of 16,000 pounds of tobacco per year raised from local taxpayers.

The Anglican Book of Common Prayer included praying for the King of England, who was also the head of the church. By the mid-1770's, such an endorsement of the king was unacceptable in many Virginia parishes.

Many Anglican ministers avoided the impacts of the America Revolution by returning to England. In the absence of replacements arriving from Great Britain, lay leaders in the vestry arranged for religious services or churches simply closed down.

Almost another decade of debate was required before the Church of England finally lost its status as the "established," official church in Virginia. The church was "disestablished" in 1786, when the General Assembly passed the "Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom," revising the bill which Thomas Jefferson drafted originally in 1777 as Bill No. 82.

Had the Anglican ministers chosen to support colonial authority in the 1750's and 1760's, rather than ally with royal officials in hopes of winning back pay, the Church of England may have morphed after 1776 into the Church of Virginia. It could have retained its primary status as the state's official religion, supported in some way with taxpayer funding. Instead, Virginians abandoned the Church of England and chose to becomre members of other denominations.

Patrick Henry portrayed the Church of England as an oppressive agent of English governmental power in the 1763 Parsons' Cause case

Source: Encyclopedia Virginia, Patrick Henry Argues the Parsons' Cause (c. 1834 painting by George Cooke, now at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture)

Before 1776, repression of dissident ministers by Virginia officials also undercut public support for the established church. Some Separate Baptists who refused to get official licenses, and who drew large crowds to worship services, were a target for Anglican ministers who resented the competition.

In several counties, Anglican ministers willing to force conformity with Anglican beliefs recruited the county sheriff to break up "unlawful assemblies." Baptist preachers were jailed for breaking the peace and preaching without a license, and even dragged from the pulpit and whipped in public. A mob in Stafford County tossed a live snake and a hornets nest into a Baptist meetinghouse.

Though Anglican ministers may have cared about religious orthodoxy, local officials may have been more alarmed by the threat created by religious dissidents to the traditional social order. Anglicans in a parish were governed by a vestry in which existing members chose replacements for those who died or retired. In contrast, Presbyterian congregations elected their leaders directly.

More dangerously, Separate Baptists created mixed-race gatherings and empowered women as Baptist "deaconesses." That challenged the hierarchical colonial power structure in which the authority to own property and make official decisions was limited primarily to just white men.

Some of the gentry objected to the abuse of unlicensed preachers and to the disruption of Baptist meetings by Anglican ministers and county sheriffs. James Madison, though a wealthy slaveowner and member of the gentry, had been educated by Presbyterian clergymen at Princeton. He was appalled by the mistreatment of Baptists in Caroline and Culpeper counties and came to their defense.

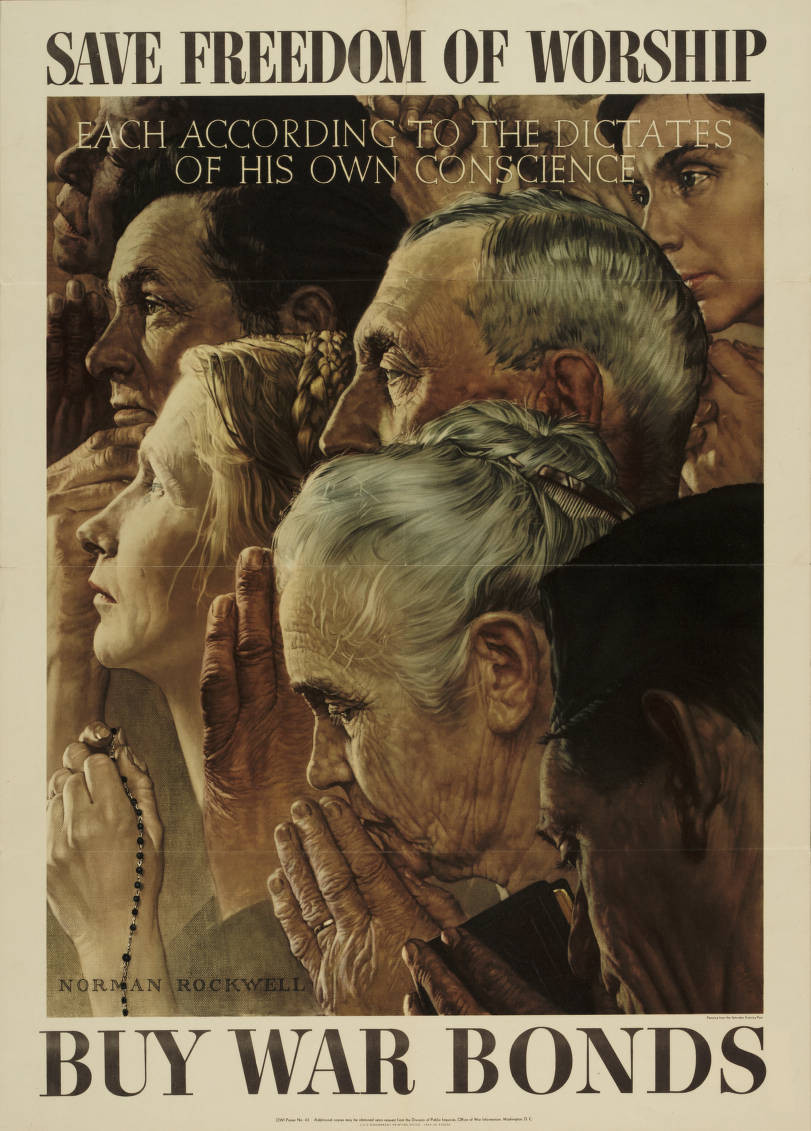

The start of the American Revolution forced a break first with Parliament's authority and then with the head of the Church of England, King George III. The now-rebel leaders in the five Virginia Conventions recognized the need to generate broad public support, in order to spur enlistment in the militia and Continental Army by the marginalized Baptists and Presbyterians. Perhaps 1/3 of the 200,000 white Virginians at the start of the American Revolution were dissidents. Across the 13 colonies, there were over 3,000 churches of 18 separate denominations.

In 1775, Baptists requested that their ministers receive equal status in the army being raised to fight the British. Patrick Henry led the successful effort for ministers of Anglican and dissenting faiths to be acknowledged equally in the colonial militia.

Independence created the opportunity for dissenters to obtain greater legitimacy, as the Anglicans in Virginia rejected the combined religious/political authority of King George III. So long as the head of the church was also the head of the state, rebellion against one was rebellion against the other. The political split with King George III and Parliament was accompanied by a parallel split with the authority of the Church of England.

After declaring independence, the General Assembly found no way to create a new entanglement of religious and political power. Virginia's revolutionary leaders could not identify a single denomination that would replace the Church of England as the established, official Commonwealth of Virginia religion; there were too many separate dissenting groups.

When Thomas Jefferson first drafted a document to explain why the 13 colonies were declaring independence, he wrote "We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable, that all men are created equal..."

Jefferson was unhappy with the editing done by the Committee of Five and by the Continental Congress before adopting the Declaration of Independence, but one of the few suggestions made by Benjamin Franklin helped clarify the intention to eliminate divine authority as the basis for political power. Franklin recommended Jefferson replace "sacred & undeniable" with "self-evident." That change eliminated the religious justification for empowering the new American government.17

in 1776, Thomas Jefferson accepted Benjamin Franklin's suggestion to change "sacred & undeniable" to "self-evident"

Source: Library of Congress, Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776 (Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, 1932)

For the same reason, the US Congress did not establish an official language for the new country. Assimilation of various immigrant groups into a "melting pot" in the 1700's required accommodating the German-speaking residents in particular. Leaders after the American Revolution sought to build a closer sense of national identity, but without defining English-speaking residents as privileged with higher status.

As ceremonies to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution began in 2025, however, President Trump broke tradition. His campaign for a second term had highlighted perceived threats from immigrants, particularly those crossing the border with Mexico. President Trump had the Spanish-language version of the official White House website deleted, and issued an Executive Order that defined English as the official language of the United States of America. Over 30 states had already adopted English as their official language for dealing with state agencies, while Hawaii and Alaska also defined additional languages within those states as "official."

The Executive Order eliminated the requirement, started in 2000, for Federal agencies to provide language assistance to non-English speakers. At the time, over 20% of residents within the United States spoke one of 350 languages other than English at home, but over 90% had the ability to speak English "very well." Canada had already defined both French and English as the official languages of that country, while Mexico (and the United Kingdom) did not have one.

Starting in 1776, Virginia's leaders structured a new form of government in which individuals could choose their own church, rather than have the government define the "right religion." The process of breaking with the Church of England occurred in fits and starts; the official split ("disestablishment") did not occur until 1786.18

The June 12, 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights established a clear separation between the authority of the state vs. the power of the individual regarding faith and religious practices. Virginia's revolutionary leaders specifically rejected the power asserted by the King of England to be Defender of the Faith, with the authority to establish official religious dogma. Section 16 of what became the "Bill of Rights" in all Virginia constitutions stated instead:19

Referencing "Christian forbearance" prioritized that faith over others. In the 1901-1902 convention that revised the state constitution, an effort was made to remove the adjective "Christian." The proposed change was intended to clarify that the state government in Virginia was completely neutral regarding different faiths; Jewish forbearance was as relevant as Christian forbearance. That effort failed in 1902.

When amendments were prepared in 1969-1970 to essentially replace the 1902 constitution, State Senator Henry Howell tried again to get the word "Christian" deleted. That effort also failed. The reference to Christian forbearance is still in the state's constitution.

The 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights had been drafted primarily by George Mason. When he finally arrived to join the debates, the president of the Fifth Virginia Convention, Edmund Pendleton, declared optimistically:20

Mason's first draft for the Fifth Virginia Convention had proposed only that "all Men shou'd enjoy the fullest Toleration in the Exercise of Religion." However, 25-year old James Madison successfully argued that the draft should be revised beyond "toleration" which could be revoked by the legislature. Madison took the lead on the religious liberty issue during the Fifth Virginia Convention in part because Thomas Jefferson was at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

Madison pushed for the declaration to be amended so it defined religious belief as a natural right, one which could not be directed by government. George Mason endorsed Madison's revision of his draft, and the final document ended up saying:21

Madison prevented the newly-independent Commonwealth of Virginia from basing its authority for governing people on a religious basis

Source: Pinterest, Trust and obey coloring page

However, the convention rejected Madison's proposal (...no man or class of men ought, on account of religion be invested with peculiar emoluments or privileges) to disestablish the Church of England and block public funding for all churches. Changing the traditional perspective of the relationship between church and state, and separating the two in Virginia, required another 25 years.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was the boldest in all the colonies for separating church and state. It came at the start of the American Revolution. Religious dissidents recognized that the need to recruit soldiers would once again create an opportunity to eliminate the obligation to fund an established church with a different faith.

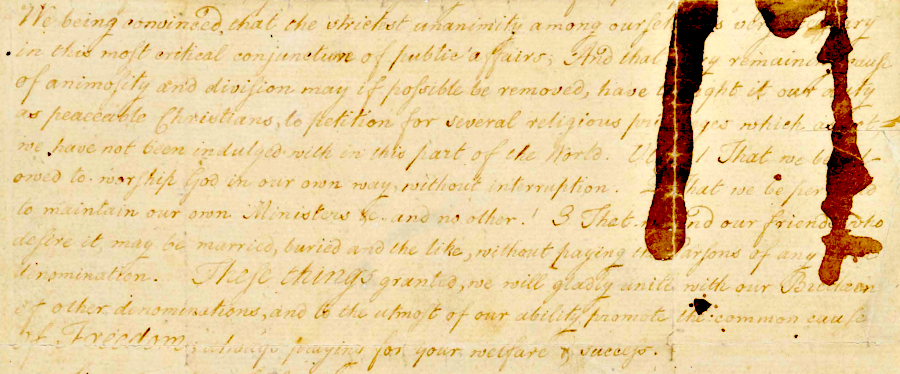

On June 20, 1776 the the Fifth Virginia Convention received a petition from the Baptists in Occoquan making clear that local dissidents linked their support for the convention's policies with the convention's support for religious freedom. The petition asked:22

Baptists in Occoquan petitioned to eliminate powers of the Church of England, as a condition of their support for the policies of the Fifth Virginia Convention in 1776

Source: Library of Virginia, Petition of members of the Baptist Church at Occoquan, 1776 June 20 (laid before the Convention)

Through legislation by the General Assembly, Virginia became the only state to eliminate religious restrictions that limited who could be elected to office. Catholics were finally allowed to serve, if they could get elected despite continuing local bias among the voters. Only the traditional ban on ministers being elected to the legislature was retained by the General Assembly.

After 1776, New England states continued to require compulsory financial support for religion. The Massachusetts tax to support "public Protestant teachers of piety, religion, and morality" did allow taxpayers to designate their payment to their own denomination or sect, so long as it was Protestant. The Maryland Declaration of Rights authorized the state to collect a tax to support religion, though the state never passed such a tax (emphasis added):23

Jefferson consulted Mason's Declaration of Rights when preparing the Declaration of Independence in June, 1776. However, based on feedback from Benjamin Franklin, the initial reference to "sacred" authority was removed from the Declaration of Independence. The Articles of Confederation, approved by the Continental Congress and 1777 and finally ratified by the states in 1781, included only this mention of religion in Article III:24

even after adoption of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, non-Anglican worship services were disrupted and preachers were harassed

Source: Library of Congress, Religion and the Founding of the American Republic, The Dunking of David Barrow and Edward Mintz in the Nansemond River, 1778

After Virginia declared independence in 1776, the Fifth Virginia Convention edited the Book of Common Prayer. The legislature mandated that prayers for the King and Realm of England be removed. In that requirement, the new state government continued the pattern of telling ministers what to preach in their religious services. Anglican ministers had to comply, leave the pulpit for some other line of work, or return to England.

The new General Assembly inherited from its colonial predecessor an established church, with 98 parishes created prior to independence. What had been the Church of England became the Church of Virginia, and became known as the Protestant Episcopal Church. One result was that the official link with the Diocese of London was broken, and there was no bishop in America who was authorized to ordain new ministers.

The long tradition of an intertwined shurch and state did not evaporate overnight. In 1776, when the 6th Virginia Regiment was being organized at Williamsburg, the colonel ordered his soldiers to attend church at 3:00pm on a Sunday afternoon.

soldiers in the 6th Virginia Regiment were commanded to attend church on a Sunday in 1776

Source: Huntington Library, Orderly book of the 6th Virginia Regiment, with records of Flatt Creek and Grove Brook plantations, 1776-1811

During the American Revolution, the Virginia legislature continued to create new parishes as population expanded. Six more were authorized by 1780, reaching a total of 104 parishes. Parishes were responsible for some government services such as care of the impoverished and orphans, in addition to overseeing worship services and hiring ministers.

Vestries continued to exercise authority at the local level in parallel with county courts during and after the American Revolution. Members of the vestry appointed their replacements on the vestry, so members of the elite gentry always stayed in control. Local residents had no opportunity to vote for the vestry members who hired ministers. Local residents also lacked the ability to vote for the justices of the peace who formed the local court; those county officials were appointed by the General Assembly.25

The first Constitution of Virginia, adopted in June 1776, created three branches of government - legislative, executive, and judicial. No religious institution was created as a fourth branch of government.

The 1776 state constitution prohibited all ministers from serving in the General Assembly. That ban minimized the potential that enough religious officials could gain power and impose their beliefs on others. Throughout the colonial period, no ordained minister had been allowed to serve in the House of Burgesses. On the rare occasions when a minister was elected, the burgesses blocked the minister from taking his seat. The Governor's Council was not restrictive, however, and the Commissary of the Bishop of London sat on the Council.

After the 1836 elections for the General Assembly, the legislators had to act on that ban. A Methodist preacher, Humphrey Billups, was elected to the House of Delegates. The decision was clear - his credentials were rejected by a 179-2 vote.

The ban on ministers serving in the General Assembly was retained in all revisions of the state constitution until after the Civil War. The "Underwood Constitution" of 1870 finally eliminated the prohibition.26

After adoption of the state constitution in 1776, sheriffs in Virginia counties continued to collect mandatory taxes used to pay salaries of the Anglican ministers remaining in Virginia parishes. Ministers from other denominations received no such funding from the state government. Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and other dissenters organized a petition drive to end the requirement to pay taxes to support the established church.

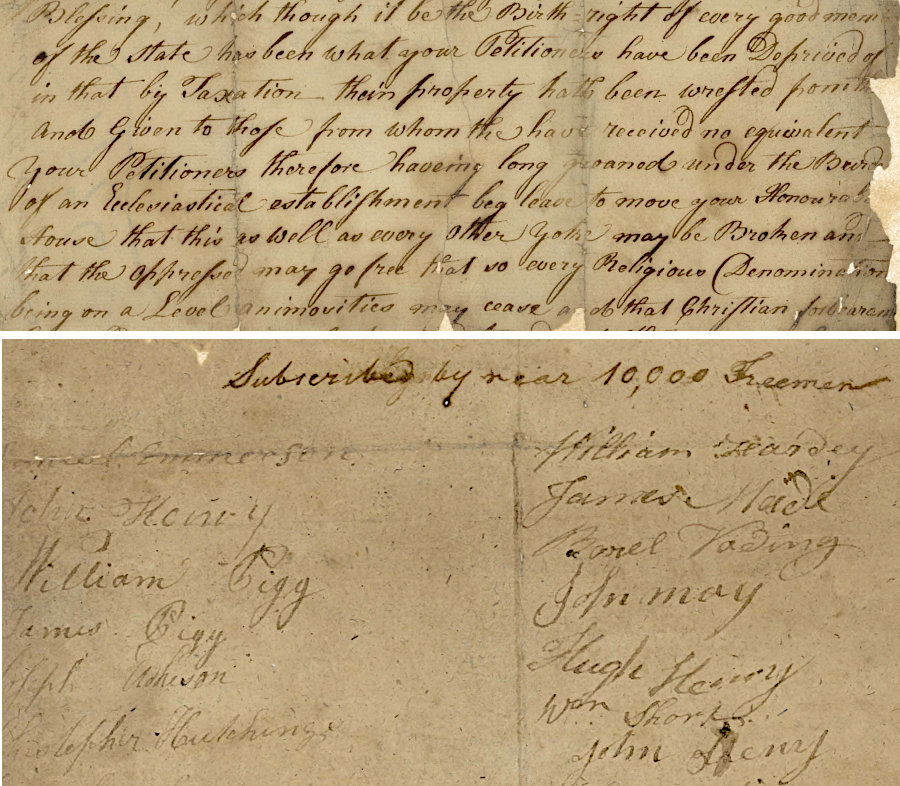

Advocates sewed together 100 pages to create an impressive "Ten Thousand Names Petition," and it was submitted to the General Assembly on October 16, 1776. The legislature responded by passing "An act for exempting the different societies of Dissenters from contributing to the support and maintenance of the church as by law established, and its ministers, and for other purposes therein mentioned" on November 19, 1776.

the Ten Thousand Names petition was part of the 1776 campaign by dissenters to end state-required taxation to support the established Church of England (Anglican Church)

Source: Library of Virginia, Dissenters: Petition

That bill temporarily suspended the state's funding. Anglican ministers had to rely upon donations plus revenue generated from glebes. Farming and other activities on the glebe were expected to generate income to supplement the salary provided to the minister.

The glebes were parcels of land previously acquired by local vestries when a parish had been created, or when enough funding had been obtained to purchase a tract of land. The funding to purchase glebe lands came from a tax set by the vestry and collected by the county sheriff.

The same 1776 law that suspended the tax to support Anglican ministers explicitly authorized the vestries to continue to levy a tax in order to provide services to the poor. The Church of England remained the official state church. The legislature did not change the powers of the established church to manage local social services such as caring for the indigent and the infirm who were impoverished, adoption of orphans, and dealing with illegitimate children of indentured servants. Vestries were tasked with civil duties, and funded so those duties could be performed.

The law also protected the existing property rights of the Anglican vestries:27

a replica of the Ten Thousand Names Petition, on display at the Library of Virginia

Source: UnCommonwealth blog, Library of Virginia, "That The Oppressed May Go Free": A Petition To The Virginia General Assembly For Religious Freedom

Philosophically, Jefferson thought that the opinions of men are not the object of civil government, nor under its jurisdiction. He sought to eliminate government authority over religious beliefs and practices, but was unable to get a majority of the General Assembly to support his approach in 1776. At the start of the American Revolution, the legislators had higher priorities to address.

The Continental Congress did make clear that it supported religious freedom in 1776, long before the First Amendment was added to the constitution that would be ratified in 1788. It decided on August 14, 1776 to issue a proclamation to the German troops brought by Great Britain to New York and invite desertion. To incentivize the "Hessians" to choose to live in America, the Congress said:28

After 1776, the Church of Virginia no longer received funding from the taxpayers and had to rely upon voluntary contributions plus income from its glebes and other property. However, it had not been "disestablished." It remained the official church of the new Commonwealth of Virginia. Those who were not Anglicans were still dissenters from the official government faith.

For the first decade of independence, Virginia legislators discussed the possibility of using taxpayer funding to support all religions. Mandating a "general assessment" for distribution to all religious denominations was a politically attractive way to restore the funding for the Anglican ministers. Rather than list which specific denominations qualified for funding, the proposal for a general assessment would allow a group of five males to form a church and qualify for public funding.

Under that approach, mandatory taxes to support churches would be collected. Funding would be distributed to different faiths, and in some proposals the taxpayer could specify the recipient. Anglicans, who began calling themselves Episcopalians, were strong supporters of renewed financial support from the state. Some dissenters supported that approach, recognizing it would guarantee funding for their religious organizations.

Thomas Jefferson opposed the concept of state-supported religion. He drafted his "Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom" first in 1777, when he was part of a team rewriting Virginia's colonial laws to reflect the new condition of independence. He started as one member of a five-person Committee of Revisors that included George Mason, Thomas Ludwell Lee, George Wythe, and Edmund Pendleton.

All five were together in Fredericksburg on January 13-17, 1777 when Jefferson drafted "Bill No. 82: A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom." Mason and Lee soon dropped off the Committee of Revisors, and Jefferson ended up doing most of the work preparing 126 bills to establish a new foundation for Virginia law.

In his research, Jefferson discovered that there was no single law which "established" the Church of England as Virginia's official religion. Multiple laws had to be revised in order to accomplish his goal:29

After being elected governor in 1779, Jefferson served on the Board of the College of William and Mary. He had the program of education revised to eliminate the training of Anglican ministers. The school had been chartered in 1693 so:30

The College of William and Mary had trained ministers for over seven decades. Until the American Revolution, those who qualified would travel to London to be ordained before returning to Virginia and serving in a parish.

Jefferson transformed the curriculum and eliminated all of the religious training. Funding for the Divinity School was diverted to other college expenses and the college became a secular institution.

Jefferson thought his "Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom" might pass the General Assembly in 1779. It was introduced as Bill No. 82, one of five bills related to religion in the list of 126 bills prepared by the Committee of Revisors. Bill No. 82 focused on preventing the state from compelling individuals to support any particular religious group and insuring the civil rights of individuals would not be affected by their choice of faith.

Bill No. 82 did not erect a total wall of separation between church and state. It did not require the government to be 100% secular, or prohibit the state from citing religion as the basis for civic action. In its final version, the bill started with "Almighty God hath created the mind free..."

Bill No. 83 was titled "A Bill For Saving the Property of the Church Heretofore by Law Established." It would have transferred legal title to the assets of all Anglican parishes from the vestry to representatives of the members of the parish. The vestry was seen as part of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, and was not an elected body representative of the members of the parish. If it had passed, Bill No. 83 would have enabled new representatives of the parish (replacing the current vestry) to pay bills using the church's assets. The General Assembly would have cleared title to those assets, ensuring they would not be confiscated by the state.

Bill No. 85, a "Bill for Appointing Days of Public Fasting and Thanksgiving," would have mandated ministers to preach in their house of worship on days designated by the governor. The bill specified the content to be preached must be "suitable to the occasion." Those who failed to preach on the designated days could be fined 50 pounds.31

Ending public support for the established church too time. Only two of Jefferson's proposed bills passed, and only in 1786. Bill No. 82 was "A Bill for Punishing Disturbers of Religious Worship and Sabbath Breakers." Bill No. 84 limited work on Sundays to routine household chores and emergency tasks. It forced establishments to close one day a week that was intended to be dedicated to religious worship and rest. Since Christians worshipped on the "Sabbath," Bill No. 84 prioritized one religious perspective by forcing a cessation of non-essential work just on Sundays.

Passing a law to limit work on the Sabbath was not a new idea. Starting in 1610, colonial officials had passed laws prohibiting certain activities on Sundays. In the 1900's those were known as "blue laws," perhaps because they were once printed on colored paper or perhaps because indecent behavior was considered "blue."

Laws constraining activities on Sundays were renewed for almost two centuries in various forms, with a justification that a day of rest was good public policy. The blue laws always designated the Christian Sabbath as that day. Seventh Day Adventists, Jews, and other religions with a different day for their worship were not authorized to open on Sundays. In 1846, two Jews were fined for working in their office on a Sunday. After they protested, laws were revised to exempt from such punishment those who worshipped on a different day than Sunday, but selling items to the general public remained banned on Sundays.

Starting in 1974, the General Assembly exempted certain industries from the ban. Local jurisdictions could also be exepted, if approved by voters in a referendum.

Drug storeswere exempted as essential businesses because they filled prescriptions. They ended up selling non-prescription products on Sunday, while other retail stores with the same products were required to stay closed. In the Twentieth Century, Sunday sales produced the largest volume per hour during the week - but only for those stores able to open.

In 1988 the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that there were so many exceptions to the Sunday sales ban that the laws were unconstitutional "special laws." The blue laws were overturned on a legal principle, but not because they involved the state government too deeply in defining acceptable and unacceptable religious practices.32

The General Assembly's ban on Sunday hunting, first passed in 1643, survived until 2014. In that year legislators authorized Sunday hunting on private land. Sunday hunting on public land remained illegal until 2022.33

In 1779, Thomas Jefferson's Bill No. 82 faced competing legislation that would have defined the "Christian Religion" as the state’s official religion. That competing bill also failed to pass.

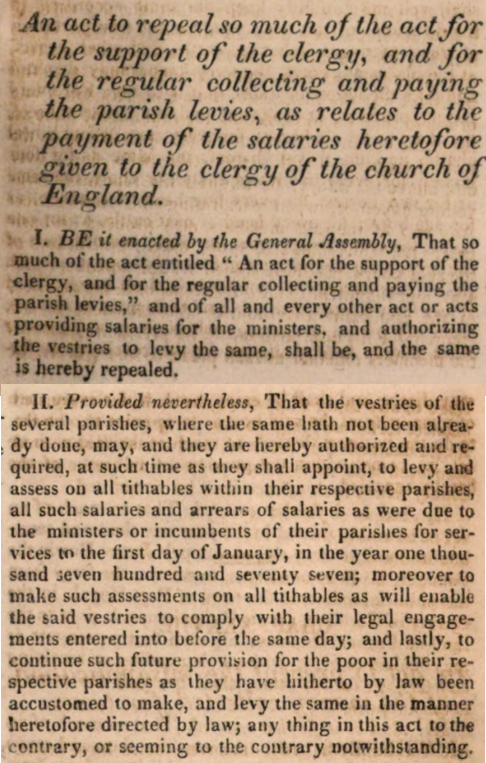

Bill No. 82 was tabled, but the mandatory tax to support Anglican ministers was permanently repealed in 1779. Jefferson's broader proposal to disestablish the official church as part of his religious liberty agenda was too radical. In 1779, the General Assembly declined to agree with Jefferson:34

mandatory payment of salaries to Church of England ministers ended in 1779

Source: William Waller Hening, Statutes at Large (Volume 10, pp.197-198)

The governmental authority of seven local Anglican vestries were constrained in 1780. The General Assembly shifted responsibility for local social services from the vestries in seven counties to a new county-managed organization, Overseers of the Poor. That reduced the cost and time burdens on those seven Anglican vestries; they welcomed the change even though it reduced their political authority.

Also in 1780, the General Assembly authorized non-Anglican, dissenting ministers to conduct legal marriages. Since marriages determined who would control and inherit property, and children were deemed legitimate only if the parents had been wed by an Anglican minister, the right to conduct marriage rites was significant. The legislature broke the Anglican monopoly and allowed:35

The General Assembly did not place Anglican and non-Anglican ministers on equal footing in 1780. The legislature limited the right to perform marriages to just four ministers of a non-Anglican congregation within a county, and county courts had to approve the four ministers. Anglican ministers remained able to perform marriages anywhere in Virginia, but non-Anglican ministers were blocked from performing marriages outside the county in which they were registered.

The limitations may have been based not on religious discrimination, but on the need to ensure marriages were recorded officially. If a person died without a will, the county courts needed to know who should inherit property according to state law. The Anglican parishes had maintained the official marriage records during the colonial era, and parish vestries - not the local courts in each county - continued to be responsible for maintaining official marriage records.36

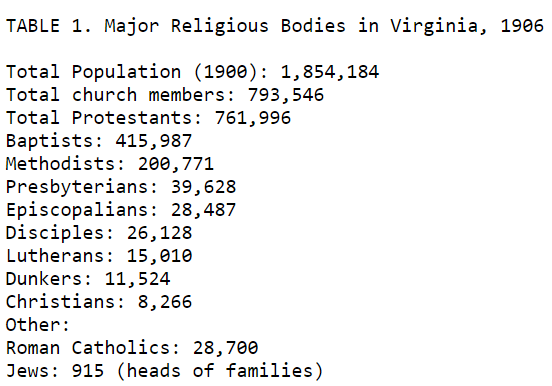

The general public understood the Church of England was allied officially with the King of England at the start of the American Revolution. That led to a dramatic decline in the influence of the Anglican/Episcopalian church in Virginia by 1783:37

After the Peace of Paris ended the Revolutionary War in 1783, Episcopalians sought to reinstate public funding for their churches. They petitioned the General Assembly to pass a general assessment and provide government-collected funding to a broad range of religious institutions. Advocates of a general tax argued that strengthening churches would address the disruptions in civil society created during the American Revolution, when the recriminations for violating the norms in Virginia's hierarchical society had largely disappeared.

More worship experiences, with more exhortations by ministers, would in theory lead to higher standards of "republican virtue" and better public conduct. Advocates of the general assessment argued that it would be in the public's interest to have taxes support religious "teachers."

Supporters of the traditional church described by 1783 as Episcopalians (no longer as Anglicans) expected to be the primary beneficiaries. They assumed the majority of Virginians would be counted as former Anglicans. The Episcopalians suggested that public support for the general assessment had become politically acceptable since the American Revolution had been successful, and counseled legislators that the need to mollify non-Anglican minorities during the period of actual fighting had diminished.

Dissenters were still very active in demanding fair treatment, however. They continued to petition the General Assembly, and the House of Delegates referred those petitions to an official Committee for Religion.

The Episcopalian clergy organized themselves and held a convention in Richmond starting on June 1, 1784. At the time, Methodists were still part of the Protestant Episcopal Church. They did not withdraw and establish a separate denomination until December, 1784.

On June 3, that convention submitted a formal petition to the General Assembly. It requested, among other items, that the Episcopalian parishes be released from the burden of managing social services at the local level.

In response, the Committee for Religion proposed on June 8, 1784 that the General Assembly repeal the laws directing how vestries must be chosen. That would get the government out of the business of managing the affairs of the Protestant Episcopal Church. The committee recommendation included assuring the Protestant Episcopal Church vestries that they retained ownership of their existing land, buildings, and other property.

The Committee for Religion also proposed that all denominations should be allowed to incorporate, so whatever they owned would be in the church's name. That would eliminate the need for church leaders to own church property in their personal names. That occasionally created complications when estates went though probate. Church property could be counted as personal assets, and sold to pay off personal debts of the deceased.

Another recommendation from the Committee for Religion was to relax the remaining restrictions on the rights of dissenting ministers to perform official marriages. The state legislature finally solved the problem of maintaining official records of marriages by mandating that all ministers report all marriages to the county court, which became responsible for maintain the official records.

On December 28, 1784, the Virginia legislature granted a charter incorporating the Protestant Episcopal Church. That created a legal organization which could control church property. At the time, the Protestant Episcopal Church still served as the official state church but retained few legal responsibilities different from other dnominations.38

After receiving its charter, the Church of England in Virginia was officially renamed as the Protestant Episcopal Church. The "new" denomination was legally independent from the Church of England, but reduced in scope. By the end of 1784, the Methodists had withdrawn to form their own organization.39

The bill incorporating the Protestant Episcopal Church was poorly worded. By mandating that lay leaders be included in the "Convention" to manage the corporation, the state government violated the Declaration of Rights by using government authority to impose requirements on he practices of a religious group.

Incorporation stimulated a negative reaction even within the Episcopalians, because it removed the right of vestries to select the minister. One of the petitions submitted to the General Assembly in 1785 calling for repeal of the charter highlighted the problem with mandating a Convention, which was composed of all the Episcopalian clergy plus one lay leader from each parish:40

In 1787, the General Assembly repealed the charter of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Incorporation had strengthened only one church's ability to maintain ownership of church buildings and glebes, giving an advantage to the Episcopalians in controlling its assets.

The proposed "general assessment" was one option for leveling the playing field. It would give state funding to support all the religious denominations. Throughout 1784 Patrick Henry had championed the "Bill establishing a provision for the teachers of the Christian religion." Henry proposed that dissenting religious groups as well as Episcopalians should receive tax revenue, so long as the dissenters were Christian:41

in the 1780's, Patrick Henry argued in favor of a state tax to fund churches; he did not advocate for total separation of church and state

Source: US Senate, Patrick Henry

Henry's effort to establish multiple religions, not just Episcopalians, as state-funded churches had at least tepid support initially from George Washington. While most dissenters were opposed to the general assessment bill, many Presbyterian ministers and the Presbytery of Hanover initially supported it. Those Presbyterians thought that public funding for religious institutions would enhance public order and morality and provide needed support for their religious leaders, even if such support would strengthen Episcopalians the most.

As James Madison described Henry's general assessment bill, taxpayers would have to option to direct which religious organization would receive their tax payment:42

However, the chartering of the Protestant Episcopal Church caused the Presbytery of Hanover to shift its position and oppose the general assessment bill in 1784. In the General Assembly, James Madison was able to have a vote on the tax issue delayed until 1785.

James Madison then allied with George Mason and led the charge against the bill in the House of Delegates. He published, anonymously, his Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments in June, 1785. Madison avoided personally alienating key legislators who were supporting the general assessment bill by disguising his authorship, and did not publicly acknowledge it until 1826.

In the Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments, Madison argued that religions could thrive without public funding, Due the power of their beliefs, churches could attract enough willing followers to fund church operations, including paying their ministers. Government funding was presented as a threat, an incentive to alter a church's fundamental beliefs to gain public support. Religious institutions would be corrupted by their efforts to retain public funding. In addition, giving government any power over religious organizations would lead to excessive use by elected officials of the power to shape religious decisions, in order to enhance political popularity.

Madison included in his Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments:43

As Madison agitated in the General Assembly throughout 1785, those across Virginia who opposed the general assessment bill submitted petitions against it. The opponents convinced the legislators that they were more numerous than the supporters. It helped that the powerful voice of Patrick Henry had been removed from the House of Delegates by electing him as governor.

At the end of 1785 the legislators dropped the proposed tax, the "general assessment" which Patrick Henry had championed.

Madison followed up on his victory in the debate and quickly introduced the "Statute of Religious Freedom," building on the language which Thomas Jefferson had drafted in 1777. Madison was successful in getting his bill adopted, in part because he agreed to delete Jefferson's draft preamble. It had articulated his sense of the supremacy of reason over faith:44

When the General Assembly voted on the Statute of Religious Freedom, the legislators were meeting at what is now the corner of 14th Street and Exchange Alley in Richmond. The Valentine Museum's Valentine First Freedom Center and Monument now marks the spot.

In a 66-38 preliminary vote in December 1785, the House of Delegates rejected language which would have weakened Madison's bill. As approved finally on January 16, 1786, the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom said:45

Virginia had an official government-sponsored church not only during its colonial period from 1619-1776, but also from 1776-1786 when Virginia was a state. When the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom was approved on January 16, 1786, it finally disestablished the Protestant Episcopal Church as the official state religion. In modern times, January 16 has been designated "National Religious Freedom Day."

To replace the role of vestries in performing local social services, Overseers of the Poor were appointed in all counties. The General Assembly repealed the charter of the Protestant Episcopal Church in 1787, but all Episcopalian church property - glebes, buildings, furniture, communion plates, etc. - still remained under the control of the vestry. Dissenters were unhappy because some of the property had been donated to the parishes, but most had been acquired using government-required taxes paid by local residents who may not have shared the Anglican faith.46

Jefferson was particularly proud of his role in drafting what became the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. The final version had been revised during the approval process within the General Assembly, and Madison had led the political campaign to get legislative approval while Jefferson was in Paris serving as the American minister to France, but everyone recognized Jefferson's role as the original author. He included on his tombstone:47

After passage of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786, dissenters continued to press for the property of Episcopalian parishes acquired in the colonial period to be confiscated by the state.

The Presbyterians initiated a campaign to sell the glebes in 1787. The Baptists then took the lead. Starting in 1789, the Baptist General Committee sent a petition annually to the General Assembly requesting that the glebe lands be converted to public use. Their fundamental argument continued to be that the glebes had been purchased with taxes paid by all residents during the colonial era, and it was unfair that only Episcopalian ministers were receiving benefit from them.

Conservatives in the House of Delegates blocked annual proposals to sell the glebes. They argued that few dissenters had paid taxes to purchase the land except in counties west of the Blue Ridge, since most glebes had been acquired before 1750. Until then, nearly everyone east of the mountains was an Anglican, except for some Quakers.

In 1796, the French Revolution created a stronger push for change in Virginia. The Episcopalians calculated they finally would lose a vote in the state legislature, so they sought to have a court decision to resolve the status of their claims to the glebes. Transferring the issue to the judicial branch was not successful.

On January 24, 1799, the General Assembly repealed seven previous acts which were perceived as inconsistent with the Bill of Rights, because they mixed government and ecclesiastical authority or provided undue support to one denomination.

The laws were repealed because they:48

Primary reason for the repeal was to eliminate the 1776 guarantee that Anglican church property would remain under the control of vestries. The 1799 law repealed "An act for exempting the different societies of Dissenters from contributing to the support and maintenance of the church as by law established, and its ministers, and for other purposes therein mentioned," which had protected vestry rights to property when passed on November 19, 1776.

For the next two years, there were discussions on how to sell the glebes - including land, enslaved workers raising crops and livestock, and the buildings in which ministers lived - and what to do with the money. In 1802, the General Assembly passed the "Act Concerning the Glebe Lands and Churches within this Commonwealth." It authorized the sale of glebe lands upon the death or resignation of the current rector (minister) of a parish in the Protestant Episcopal Church. The requirement that the pulpit be empty avoided pushing a minister out of their home while they were still actively preaching and had a group of supporters in the community.

Proceeds from the sales were delivered to the Overseers of the Poor in that county, for establishing and supporting local academies for public education, and to reduce taxes. There were some cases where individuals took advantage of the sales for their personal benefit, such as using the land after the death of a minister until the sale was completed but not paying any rent.