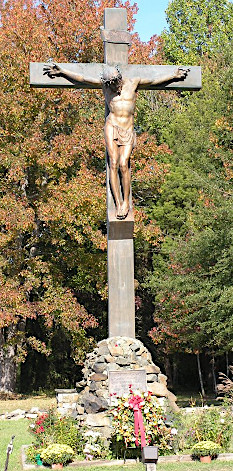

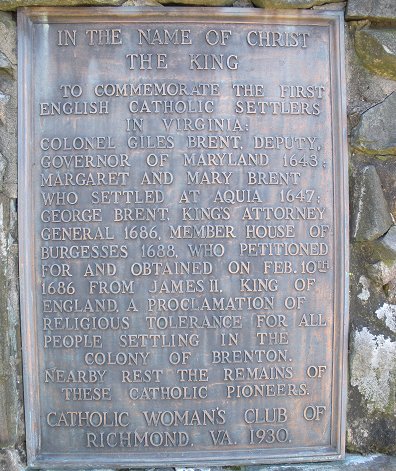

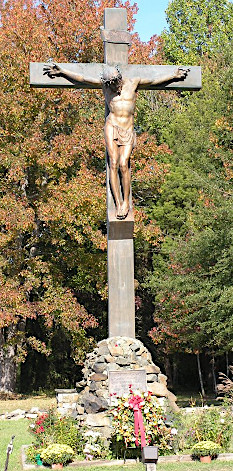

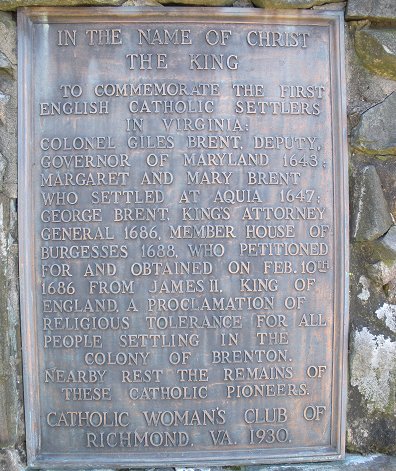

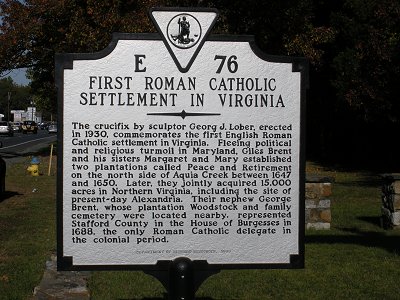

inscription on statue honoring Brent family on Route 1 in Stafford County

inscription on statue honoring Brent family on Route 1 in Stafford County

When Virginia was started as a colony, religious differences were political differences. Religious dissent was potentially treason.

Political authority and religious authority had been centralized in England since Henry VIII had rejected the authority of the Pope in the 1530's and established himself as the head of an Anglican Church. The English monarch was the head of the church as well as head of the state, and all government officials had to take the Oath of Supremacy.

When Queen Mary assumed the throne, her Catholic faith created political conflict. She was the daughter of Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon - a Catholic from Spain. Queen Mary sought to re-establish the Catholic faith as the state religion, following the tradition in Europe that the religion of the monarch became the established religion of the country, but died before completing the process.

Queen Mary was replaced by Queen Elizabeth I, who restored Protestantism as the official religion in the 1559 Act of Uniformity and Act of Supremacy. Mary Queen of Scots fled to England to escape her Protestant nobles, and Elizabeth I provided shelter initially.

Catholic Spain settled the New World first, and the Spanish Armada attacked England as it started a colony at Roanoke Island

Source: Library of Congress, Columbus taking possession of the new country

Religion and politics were tightly connected within the ruling circles of England during the 1500's. Mary Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I were both descendants of Henry VII. That stimulated plots to assassinate Elizabeth I and replace her with Mary Queen of Scots. After being presented evidence that the plots were encouraged by her Catholic relative, Queen Elizabeth I signed a death warrant and had Mary Queen of Scots executed.

When the "virgin queen" died, the closest royal relative in line to assume the throne was the son of Mary Queen of Scots, James VI of Scotland. He had been raised as a Protestant, so he was acceptable and became James I of England. In the Gunpowder Plot in 1605, Catholics demonstrated the connection between treason and faith when they attempted to assassinate King James I and blow up Parliament.

Source: Science Museum of Virginia, Lunch Break Science: How a Terrorist Failure in 1605 Enabled Jamestown and Henrico

The threat of another Catholic ruler throughout the 1600's exacerbated the political differences between the king and Parliament. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 finally established the primacy of Parliament, and the 1701 Act of Settlement blocked any Catholic from ever becoming the monarch in England.

James I died soon after revoking the charter of the Virginia Company in 1624. His son Charles I ended up becoming the first English king with control over the Virginia colony. Charles I made two key decisions affecting religion in Virginia.

In 1632, he reduced the size of Virginia by granting land north of the Potomac River to create the Catholic colony of Maryland. The first Maryland settlers landed on St. Clement Island two years later. There they celebrated the first Catholic mass in North America by English settlers in North America on March 25, 1634. Of course, earlier Spanish and French settlers - and perhaps some English sailors, in private - had been conducting various forms of Catholic rituals and formal masses in North America long before 1634.

The second key decision by Charles I impacting religion in Virginia was his appointment in 1643 of Sir William Berkeley as governor. Berkeley proceeded to force out of Virginia the Puritans, Quakers, and others who did not conform to the Anglican style of worship.

The marriage of Charles I had been a matter of foreign policy rather than love. The priority of James I was for his heir to marry a Catholic, to increase the potential of gaining control over lands in Europe. An area in the Palatinate claimed by the son-in-law of James I, Frederick the Elector, had been occupied by the Spanish Army during the Thirty Years War. James I's daughter Elizabeth had married Frederick the Elector, and a century later her grandson would become King George I.

Charles I traveled secretly to Spain, but efforts to negotiate a marriage to the daughter of King Phillip III collapsed and he returned to England in humiliation. He then pressured his father, James I, to create an alliance with Catholic France and to support military conflict in Europe in order to expel the Spanish from territory along the Rhine River. The French alliance could be secured by a marriage between Charles I and Henrietta Maria, daughter of King Henry IV of France and sister of King Louis XIII of France.

The relationship started off with some difficulty. Charles I did not actually travel to France for the wedding. He sent a representative, which was an acceptable practice rather than a snub. Charles' proxy did not enter Notre Dame Cathedral to witness the ceremony. He did not attend the Catholic rite in person because England was officially a Protestant nation. Though the marriage was arranged for political reasons, to encourage an alliance between those rival governments, the two later fell into love.

The reverse occurred when Charles was crowned as king. Maria was unable to attend the coronation in person, since it was a Protestant ceremony and she was a Catholic. ChArles II was succeeded by his brother King James II, who was a Catholic. In the 1688 Glorious Revolution, Parliament succeeded in forcing him to flee England.

Queen Mary and her husband King William became the new monarchs. After the death of King William, a new line of succession based on Protestant rulers was established with the coronation of King George I. Descendants of King James II stimulated two Jacobite rebellions, but were unable to regain the throne.1

Though toleration was granted in England, there was only one official church in Virginia during the colonial period. Royal governors never welcomed Catholics in the colony. Even for a decade after the start of the American Revolution, there was no guarantee of religious freedom in Virginia.

Religious conflict was still a factor in Virginia politics, but colonial leaders minimized the Anglican-Catholic conflict by excluding non-Anglicans. On September 10, 1607, the first president of the Council in Virginia was forced to step down and imprisoned. Others on the Council accused Edward Maria Wingfield of being an atheist or Catholic sympathizer sympathetic to Spain, though his arrogant style of leadership might have spurred a desire to force him out of his leadership role. The religious charge was a serious affair. When Christopher Newport returned to the colony in January, 1608, he released Wingfield from prison but kept him off the Council, then took him back to England for trial in April 1608.

More seriously, Captain George Kendall was forced off the Council in 1608 and executed after being accused of being a Catholic. Six crucifixes discovered by archeologists at Jamestown document the presence of Catholics in the early colony, but they had to keep their religious beliefs a secret in order to avoid punishment.

Spies for Spain, possibly Catholic sailors on visiting ships or colonists in Virginia as well as in England, provided regular updates to Spanish officials on the status of the struggling colony. One known Catholic was kept captive at Jamestown for five years. Captain Don Diego de Molina led his Spanish ship into the Chesapeake Bay in 1611 and rowed ashore at Point Comfort. He claimed he was blown off course, but when the English began to row out to the ship it sailed away. Diego de Molina and two others were abandoned. Before he was shipped back across the Atlantic Ocean in 1616, he managed to smuggle at least one letter in 1613 to the Spanish Ambassador in London.

When archeologists excavated the grave of Captain Gabriel Archer in 2013, a Jamestown leader buried in 1609 within the walls of the first church, they discovered a silver "reliquary" which had been placed on top of his casket. Inside the silver box was a tiny lead vial ("ampulla") and seven bone fragments. Catholics traditionally were associated with reliquaries, using them to contain holy relics such as an ampulla holding holy water, oil, or blood.

Because the leaders of the Virginia Company insisted on religious conformity with the Church of England to minimize social conflicts, it is unknown how many of the first English colonists in Virginia were Catholic:2

Source: Jamestown Rediscovery, Finding Captain Gabriel Archer

Starting in 1607, the only ministers sent by the Virginia Company were Anglican. Under Queen Elizabeth I and then King James I, that denomination was "established" as the official church of England. When it became a royal colony after the Virginia Company's charter was revoked in 1624, the connection between church and state was even more official. Virginia was always an Anglican colony.

After 1634, however, there were always Catholics on the northern Virginia border.

As part of the English-French marriage treaty for the son of James I, Charles I secretly promised to relax restrictions on Catholics in England. His willingness to support Catholics, perhaps influenced by his wife, was revealed in part when he granted a charter for the colony of Maryland. The charter was originally intended to be a grant to George Calvert, who had served as Secretary of State and Privy Counsellor to James I. George Calvert converted to Catholicism and resigned his official positions in 1625, but the king created the title of Baron Baltimore for him.

Soon after being appointed to high office by James I, Calvert was granted land in Newfoundland in 1620. He sent colonists to "Ferryland" in 1621, and obtained more land in 1623 for the Province of Avalon. It acquired a reputation as a haven for Catholics fleeing England. There were 100 colonists there, making a living from fishing, when Calvert personally moved to it in 1627.

By 1629 George Calvert had determined that the winters were unbearable. He requested Charles I to provide a new land grant further south in Virginia after experiencing:3

George Calvert died just before Charles I issued his 1632 charter for the requested proprietary colony. The king gave the charter to his son, Cecil Calvert, Second Lord Baltimore. Charles I requested that the new colony be named after Queen Maria, and "Maryland" was from the beginning a place where Catholics were welcome.

The Ark and Dove landed at St. Mary's Island in 1634. However, the start of the journey reflected the suspicion of Catholics in England at the time. Soon after sailing out of the Thames River, the Ark and Dove were intercepted by a ship with the "London Searcher," the man empowered to identify those who might threaten Charles I. The ships were required to return, and everyone had to sign a written oath declaring loyalty to the king.4

the Ark and Dove had to return to the Thames River and everyone had to sign a loyalty oath, before the ships could sail to Maryland

Source: James Otis, Calvert of Maryland; a story of Lord Baltimore's colony (p.27)

On March 25, 1634, Cecil Calvert's immigrants held what the state of Maryland calls:5

That claim carefully excludes Catholic masses held in Florida by Spanish settlers even prior to the settlement of St. Augustine in 1565, and Catholic masses held by Spanish Jesuits who settled in Virginia at Ajacan in 1570. In 2018 archeologists discovered the site of the fort built by colonists who included Jesuit priest, Father Andrew White. He held the "first Catholic mass in the Colonies" in 1634.

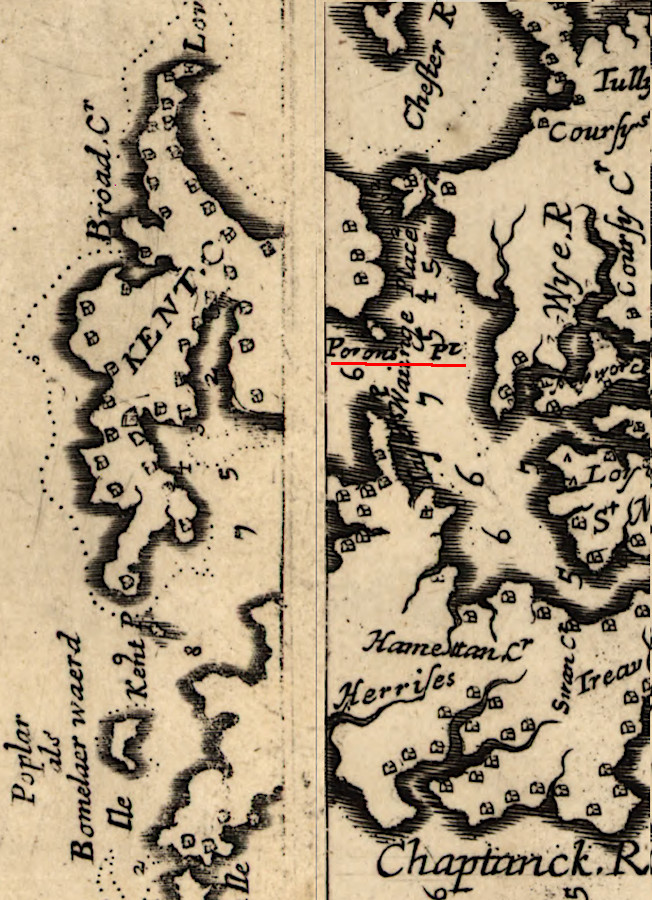

In addition, that 1634 mass was not the first Christian ceremony held by colonists in what is now Maryland. William Claiborne brought a Anglican minister, Reverend Richard James, to Kent Island. At a site soon called Parsons Point, he conducted a religious service in August 1631.6

the first Christian religious service in Maryland was performed by a Church of England minister, at Parsons Point on Kent Island in 1631

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (Augustine Herrman, 1673)

The settlers in Virginia did not appreciate the creation of Maryland. It gave to the Calverts valuable lands that the Virginians considered to be within their colonial boundaries, based on the Third Charter issued by James I in 1612. Economic interests, more than religious differences, may have shaped the initial hostility from the Virginia leaders.

The Virginia colonist most affected by the creation of Maryland was William Claiborne. He had arrived in Virginia in 1621 as the colonial surveyor and established a fur trading post on Kent Island in 1631. Claiborne was evicted by the Calverts. He appealed to Charles I that his pre-existing claim to the island should be exempted from the grant of "a Country hitherto uncultivated" to the Calverts, but Charles I backed Cecil Calvert instead of William Claiborne.

Claiborne had partial revenge against the Calverts. He spurred the Susquehannock to take their fur trading business to the Swedes in Delaware, rather than do business with the Maryland colony. Claiborne's dispute with the Calverts did not end there, however. He participated in the 1644 revolt against Leonard Calvert, seizing St. Mary's City for several years. Later, from 1652-57, he served on the Parliamentary commission that governed Maryland under Cromwell. Despite those moments of revenge, Claiborne was never able to regain control of Kent Island.

The English Civil War between Charles I and the Puritans, led by Oliver Cromwell, was a war for power and control. International alliances were based on personal connections such as who was married to whom, and national religions could change with new rulers. Charles I's perceived support for Catholicism was a threat to the Puritans, and led to the king's execution in 1649.

Maryland passed the Act of Toleration in 1649 to minimize disruption by religious conflict within the colony. That act included:7

This legislation was not based on an ecumenical movement or modern perception that each religion has value. Instead, it was a political move to attract new settlers and to minimize the threat of charter revocation by Cromwell's new government.

In the 1640's, the population of Virginia and Maryland increased through immigration more than through "natural increase" (births from existing colonists). Recruiting new settlers to serve as indentured servants was not easy. The Calverts recognized that they could attract more European immigrants, and even dissatisfied settlers from Virginia, by minimizing the threat of discrimination against Protestants by the Catholic proprietor and Catholic leaders in the Maryland General Assembly.

In contrast, colonial officials within Virginia harassed religious dissenters. In the mid-1600's, those dissenters were primarily Puritans; few Catholics tried to immigrate into Virginia. The Catholic officials of Maryland wanted to increase the population of their colony and stimulate more economic growth with greater tobacco exports, and religious conformity was a secondary concern.

Though the Puritans in England were clearly anti-Catholic, the Calverts planned to steer the Virginia Puritans to settle on the edge of their existing population centers, including Anne Arundel County. That location would make the Puritans into a buffer between the existing settlements and the Native Americans, primarily Susquehannocks living nearby and Iroquois raiders from the north. Virginia did the same thing a century later, welcoming the Scotch-Irish immigrants and the "Pennsylvania Dutch" to the Shenandoah Valley as a buffer against the threat of the French beginning to occupy the Ohio River valley.

Catholics were not officially granted the right to worship as they pleased in Virginia until after the General Assembly passed the "Act for Establishing Religious Freedom" a decade after declaring independence from England in 1776. Catholics were present in Virginia long before then, starting with the Spanish missionaries in 1570 and some of the first colonists at Jamestown in 1607.8

The official religion in Virginia starting in 1607 was the faith of the king, the Church of England, but sailors brought cultural diversity to all the Tidewater ports and plantation wharves. Colonial officials were concerned about possible attack by Catholic Spain or France in the 1600's and 1700's, but paid no attention to the religious beliefs of individual sailors who were just temporary visitors.

Settlers received closer scrutiny. Those who were Catholic were automatically viewed as people unwilling to accept the English monarch's primary role as Defender of the Faith. That made them potential traitors, possibly unwilling to accept the monarch's political as well as religious authority. Individual Catholic families were vulnerable to fines or censure. Only one Catholic, George Brent, was ever elected to the General Assembly before 1776.

roadside historical marker for statue honoring Brent family on Route 1 in Stafford County

The American Revolution changed the ability of political leaders to repress "unofficial" religious faiths. Less than 1% of the population in the 13 colonies was Catholic at the time, and by then the Church of England was the official religion in Maryland despite its orginal founding as a haven for Catholics.

However, there was diversity of official religions in different colonies and no official religion in some. Lack of uniformity made it impossible for the Continental Congress to establish one national religion for 13 separate states.

In Virginia, legitimizing religious worship of non-Anglican faiths was one tool used by the General Assembly during the revolution to recruit Presbyterians, Baptists, and German Pietists into the Continental Army and ensure they would engage as members of each county's militia.

George Washington needed support in the new American Army from Catholics as well as soldiers of other faiths. In late 1775, he blocked soldiers from conducting a traditional burning of an effigy of the pope on Guy Fawkes Day. That celebration commemorated the successful interruption of a Catholic plot to blow up Parliament in 1605. At the time, the Americans had invaded Canada and were trying to win the allegiance of Catholics in Quebec, as well as support from the Catholic kingdom of France.9

Open Catholic worship was made legal in 1786, after James Madison maneuvered the state legislature to approve the religious freedom legislation that Thomas Jefferson had first introduced in 1779. A decade earlier, Madison had revised the draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights to replace "fullest Toleration" of religion with "free exercise of religion." It took another 10 years before he could disestablish the Church of England as the official religion of Virginia.

The Act for Establishing Religious Freedom was proposed by Madison in the General Assembly when it appeared the "United" States which had been created in the American Revolution might fail. The law was adopted in 1786, three years before the US Constitution was ratified and six years before the First Amendment made the Federal protection of religious freedom explicit with very clear language:10

In 1781 during the march to Yorktown, a Catholic chaplain in the French Army offered the first public Holy Mass in Alexandria. Most sources identify the port city on the Potomac River, next to Maryland, as the site of the first Catholic congregation in Virginia. That honor actually belongs to a site much further west.

Three migrations from Maryland to Kentucky, starting in 1785 and led by the League of Catholic Families, brought a critical mass of Catholics to the western end of Virginia. They settled on Pottinger's Creek, roughly nine miles south of Bardstown Kentucky. In 1787, Father Charles Whelan organized Virginia's first Catholic congregation there.

In 1792, the same year Kentucky became an independent state, Rev. William de Rohan led the congregation when it built a log chapel at what became known as Holy Cross. It was the first Catholic church in the state, and the first American-built Catholic church west of the Alleghenies. (French Catholics at forts and settlements in the Mississippi River had built log chapels previously.)11

The first Catholic bishop in the United States was appointed in 1789, and Baltimore was the first diocese. In 1796, the first Catholic Church was completed in Virginia. The Church of Saint Mary was in Alexandria, a port city visited by sailors of many faiths. The first priests there were Jesuits from Maryland.12

The toleration of Catholics after the American Revolution lasted for a century:13

Source:

Catholic Diocese of Arlington, A History of the Diocese of Arlington | Golden Jubilee Documentary