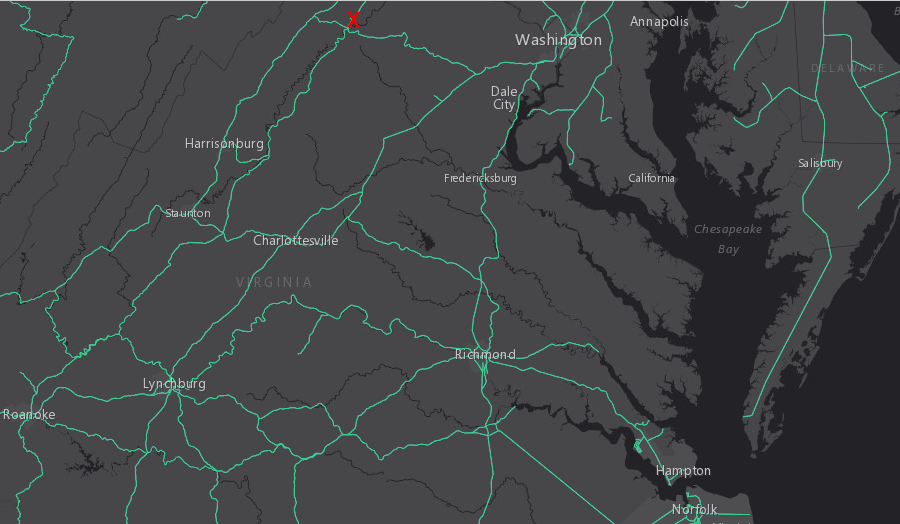

the Virginia Inland Port (red X) is connected to ocean-going ships via railroads (green lines on map), enabling containers to be moved between the Shenandoah Valley and Norfolk at lower cost than by truck

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Virginia Inland Port (red X) is connected to ocean-going ships via railroads (green lines on map), enabling containers to be moved between the Shenandoah Valley and Norfolk at lower cost than by truck

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

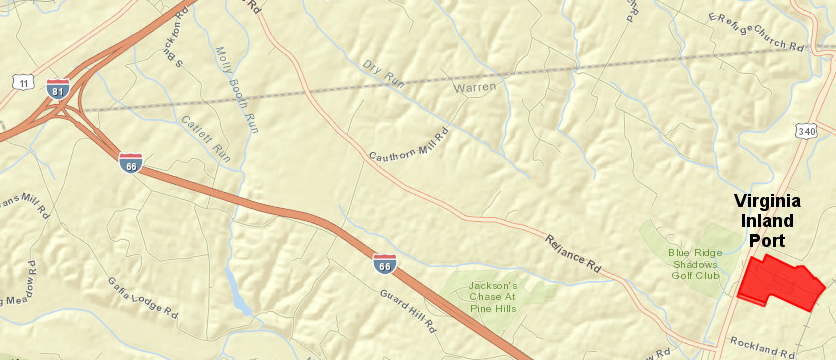

The Virginia Port Authority has built an "inland port" in Warren County near Front Royal. It is far inland from the Chesapeake Bay and even the Fall Line, where ship navigation is blocked by rapids. The Virginia Inland Port (VIP) is not even on the banks of the nearby Shenandoah River, which is so shallow that canoes have difficulty navigating its rock ledges.

Nonetheless, Front Royal is a key part of the ship-to-rail-to-truck supply line between Europe/China/other foreign manufacturers. As noted in one news article, Warren County - west of the Blue Ridge - is not an obvious location for a port:1

the Virginia Inland Port (VIP), a 161-acre facility where containers are transferred between rail cars and trucks, is far from Hampton Roads

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Front Royal 7.5 minute topographic map (2010)

The Virginia Inland Port (VIP) is next to the Norfolk Southern rail line and two interstate highways (I-66 and I-81) in the Shenandoah Valley. It was one of the first intermodal transfer facilities in the United States based on international trade, with containers shipped by rail based on their steamship bill of lading or equivalent. Though the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) is 180 west of the Atlantic Ocean, to shipping customers it is just like a marine container terminal.

The inland port was designed so trucks with export cargo from Pennsylvania, West Virginia, or the Shenandoah Valley/Northern Virginia region could transfer containers to railroad cars - not ships - at Front Royal. The site is a U.S. Customs-designated port of entry that is over 200 miles closer to the industrial Midwest, and on a highway corridor to the Northeast that is less clogged than Interstate 95.

Trucking cargo to Front Royal requires a much shorter haul than driving over the Blue Ridge or via congested roads to Norfolk. In reverse, containers imported through Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) or the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) could be shipped by rail west of the Blue Ridge, then shifted from railroad cars to trucks and carried to the ultimate destination.

at Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) and Virginia International Gateway (VIG), containers are unloaded from ships and double-stacked onto trains

Source: Virginia Port Authority VPA Sends First Double-Stack Heartland Corridor Train On its Way (September 9, 2010 blog post)

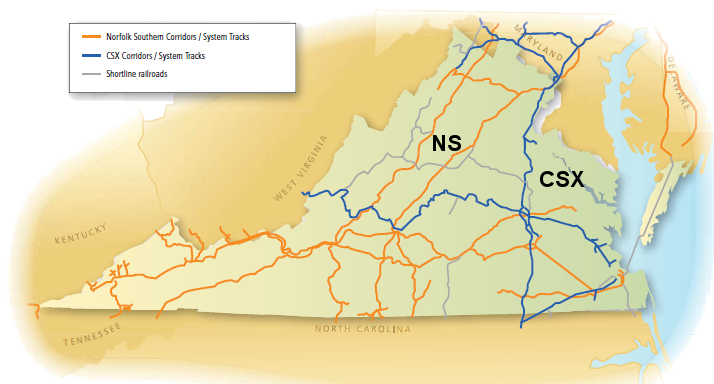

Containers that arrive via ship at Norfolk are lifted by cranes onto railroad cars, then carried by the Norfolk Southern railroad to the Shenandoah Valley. The Norfolk Southern railroad does not provide direct service at the port at Newport News or Richmond, and the CSX railroad does not have direct service to Front Royal, so shippers can simplify the shipping by sending containers via Norfolk terminals and Norfolk Southern.

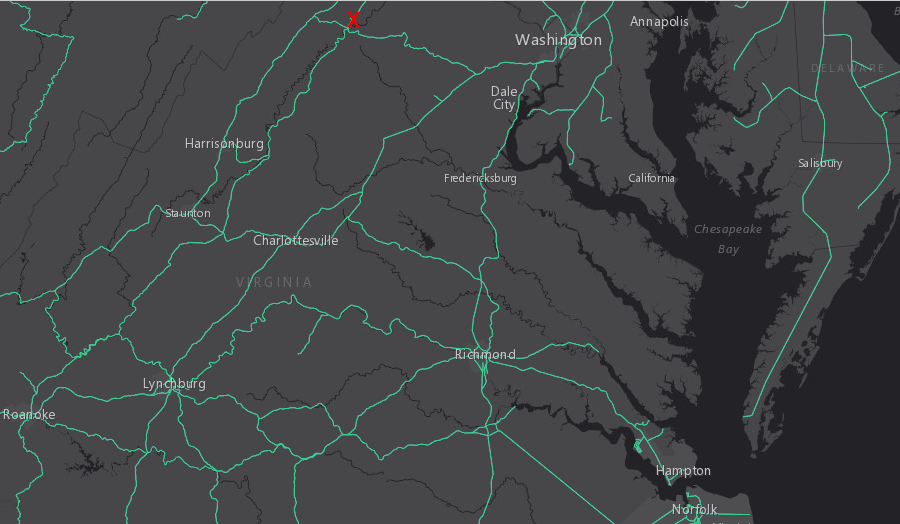

The railroad can send containers via trains from Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) or Virginia International Gateway (VIG) westward to Lynchburg, then going north to the inland port. Norfolk Southern has two options for transport between Lynchburg and Front Royal.

Trains can go via the Piedmont Line east of the Blue Ridge, crossing the mountains through the Thoroughfare/Manassas gaps via the B-Line to Front Royal. Norfolk Southern could also use its trackage rights on the CSX line to cross the Blue Ridge northwest of Lynchburg, where the James River has carved a gap at Balcony Falls, then go north via the Shenandoah Line (built as the Shenandoah Valley Railroad in the 1880's) to the Virginia Inland Port (VIP).

after trains reach Lynchburg, Norfolk Southern railroad has two options for transferring containers to the Virginia Inland Port (VIP), via the Shenandoah line west of the Blue Ridge (in black) or the Piedmont Line east of the Blue Ridge (in green)

Source: Norfolk Southern System Map

At the inland port, containers are transferred from rail cars onto the chassis of 18-wheeler trucks for final short-haul delivery (typically to destinations within 50-100 miles). The railroad would like to carry containers all the way to the customer's warehouses rather than split business with a trucking company, but not all warehouse distribution facilities are located on a rail siding.

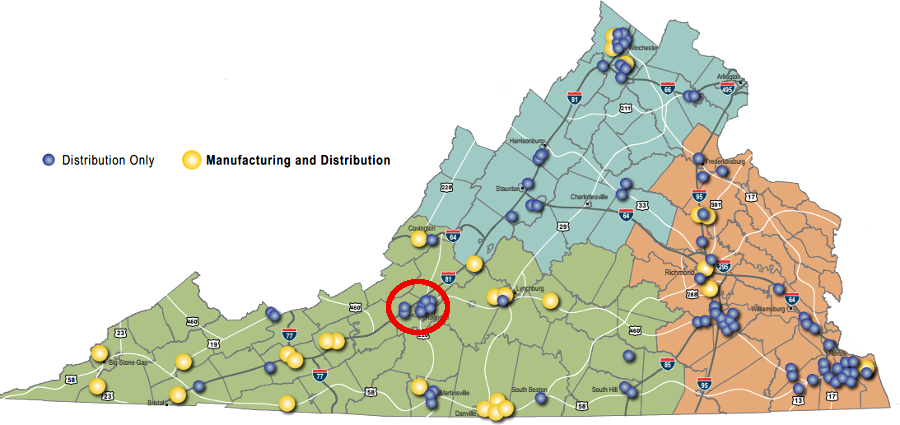

the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) supports roughly 40 distribution centers that supply Northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley,

after containers are delivered by rail from Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Port Authority Powerpoint, The Port of Richmond, Richmond's Future

The Virginia Inland Port (VIP) was created in 1989 as a competitive effort by Virginia to divert trade away from the port at Baltimore. At the time, the concept was new and even containerized shipping was not yet traditional. Port officials were comfortable with the slow development of demand to use the Warren County facility, in part because they had to familiarize and train the new workers in the Shenandoah Valley2

Primary attention was focused on increasing export traffic at Norfolk International Terminals (NIT). Virginia funded creation of the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) in hopes that companies in the Midwest, Pennsylvania, and even western Maryland (including large poultry operations) would send their containers to a Virginia port rather than to Baltimore.

As described in a feasibility study for creating a similar inland port in California:3

The Virginia Port Authority developed the first inland port in the United States after visiting the city of Venlo in the Netherlands in 1984. That European inland port attracted business from German shippers for the port of Rotterdam, located 100 miles further west:4

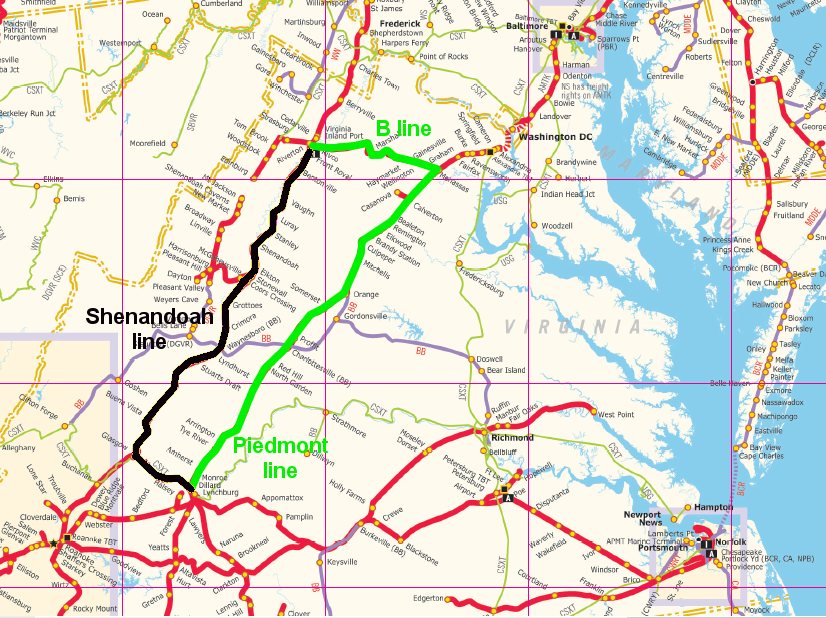

Virginia could have established the inland port closer to the I-95 corridor and steered traffic to the Newport News Marine Terminal (NNMT) via its servicing railroad, CSX. However, large parcels of undeveloped land close to the CSX line along the I-95 corridor were relatively expensive. Only Norfolk Southern connected the low-cost land available in the Shenandoah Valley with a port in Hampton Roads, so that railroad became the primary beneficiary of the traffic between Norfolk (NIT) and the inland port.

CSX railroad (blue line on map) provides rail service for Newport News and the I-95 corridor, while Norfolk Southern (orange line on map) serves Norfolk and the I-81 corridor

(CSX also services Virginia International Gateway in Portsmouth)

Source: 2008 Virginia State Rail Plan

Front Royal was not the first choice of the rail partner. Norfolk Southern wanted to increase its business and provide a longer haul by rail to a site further west. However, land was inexpensive and available at the Shenandoah Valley site, and it was near the junction of I-66 and I-81.

It is not clear how much business shifted from Maryland to Virginia, but the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) succeeded in attracting sufficient traffic (especially poultry exports) to become successful. Had the planners known how business would grow, they would have acquired 1,000 rather than just 161 acres. Economic development planners would also have ensured zoning for warehouses near the inland port, instead of allowing land across Route 340 to be developed as a golf course.5

planners failed to anticipate the level of economic development adjacent to the Virginia Inland Port (VIP), and a golf course is located across Route 340 instead of job-creating warehouses/distribution centers

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Front Royal 7.5 topographic quad (2010)

The Virginia Inland Port (VIP) started as a less-congested "satellite marine terminal," using a rail shuttle to bring containers 200 miles closer to customers in Northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley. Rail cars loaded with containers were tacked onto the back end of a train already headed to Detroit.

The facility was not a success initially, and attracted far less than the 40,000 containers/year projected. Shippers were reluctant to be the first company to use the new concept. Virginia Port Authority officials invested in offering reliable service, running a train daily (Monday through Saturday) from Front Royal to Norfolk even when the volume of cargo was very low.

The inland port began to thrive after a labor strike interrupted exports at Baltimore in 1990. The quick response by Virginia officials to redirect rail traffic to Norfolk impressed customers. The labor strike interrupted service at Baltimore for only three days, but the event changed the perceptions of shippers. Companies redesigned their shipping patterns based on the assumption that Front Royal would be a key node for imports and exports.

After Home Depot built a distribution center in 2003, the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) doubled traffic by adding 10,000 containers/year. Now that corporations have built large distribution centers nearby, the inland port has morphed into a logistics hub creating 8,000 jobs. Five times each week, freight trains bring cargo from Norfolk International Terminals to the waterless port located west of the Blue Ridge, taking 13 hours to make each trip.6

Norfolk Southern railroad transports cargo from Norfolk to the Inland Port near Front Royal, Virginia, which is within one mile of I-66 and 5 miles of I-81

Source: Warren County Parcel Viewer

North Carolina pioneered the concept of an inland port serving as a strategic rail hub, creating the first one in 1984. Once-a-week unit trains linked the Port of Wilmington to the Charlotte Intermodal Terminal in western North Carolina, near the intersection of I-85 and I-77. North Carolina dropped the use of trains in the early 1990's, before international trade via containers expanded dramatically. The North Carolina State Ports Authority shifted to a "Sprint Service," using trucks instead of rail to move containers quickly to a rail connection at the Piedmont Triad Inland Terminal in Greensboro and the Charlotte Inland Terminal 200 miles inland from Wilmington.

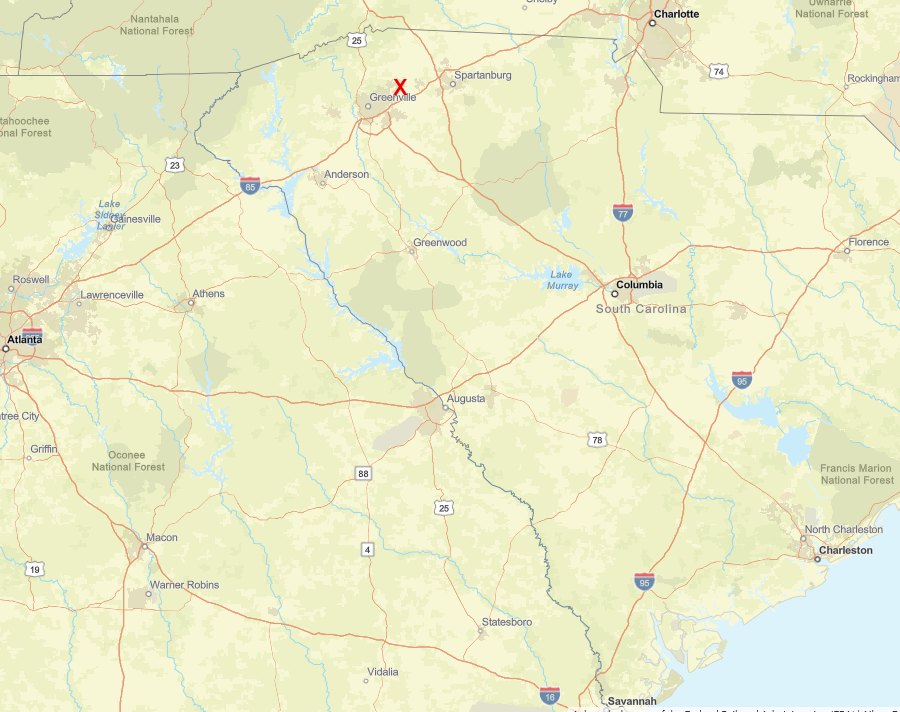

The South Carolina Ports Authority followed the inland port model in 2013. The Port Greer site near I-85 was economically challenging because it was within 250 miles of the Port of Charleston. Trucks within that range could provide significantly faster service than a railroad.

However, BMW opened a car manufacturing plant near Spartanburg and committed to 24,000 annual lifts. Acquiring an anchor tenant justified initial construction of Port Greer, and then other manufacturing facilities as far away as 150 miles chose to ship through the inland port.

By 2021, when the inland port expanded again, BMW was using Inland Port Greer to export 70% of the vehicles built in its South Carolina plant through the port at Charleston and Port Greer was processing 120,000 lifts annually. A second inland port at Dillon, South Carolina processed another 30,000 lifts.7

South Carolina built Inland Port Greer (red X) in 2013 after BMW committed to be the anchor tenant

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2014 Norfolk Southern built a new intermodal terminal at Charlotte Douglas International Airport, which required building railroad track underneath a runway. Public funding subsidies for that new facility were justified based on predicted growth of transportation-related businesses at the airport, rather than expectations that cargo would be transported from the port at Wilmington to be loaded on planes at Charlotte.

At the opening of the facility, its uniqueness was noted by the Norfolk Southern representative:8

Other states besides South Carolina adopted the Virginia model of an inland port. West Virginia focused on connecting the port at Baltimore to Martinsburg in Berkeley County, near the intersection of I-81 and I-70. Georgia planned a new inland port a Gainesville, near Atlanta and 325 miles inland from the Port of Savannah.9

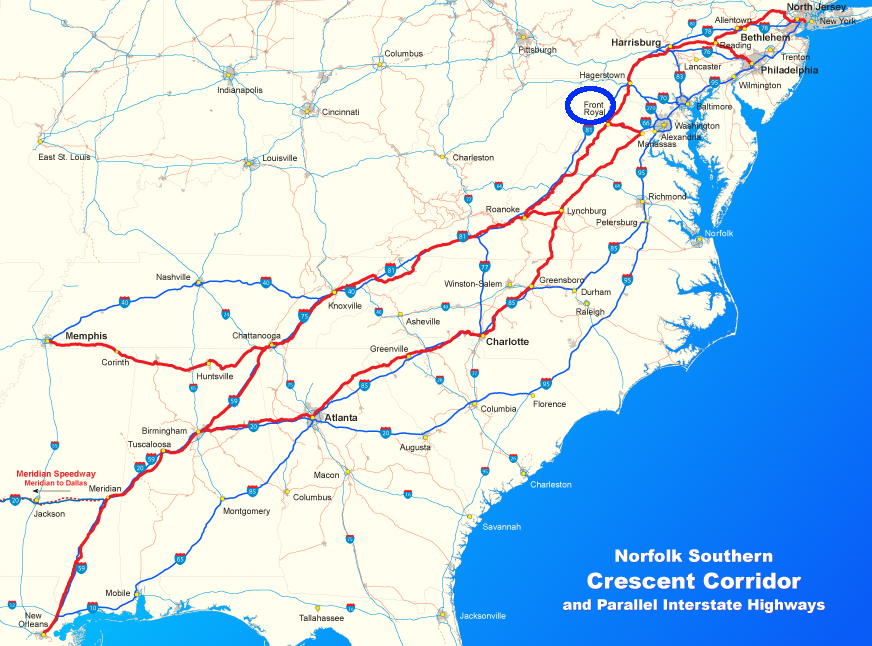

the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) near Front Royal is on Norfolk Southern's Crescent Corridor (red lines), parallel to I-81 (portrayed as a blue line) and designed to carry freight between New York-New Orleans

Source: Norfolk Southern, Photos & Sounds

State control of the Port of Virginia eliminated competition between Norfolk/Portsmouth/Newport News. The investment in creating an inland port was one of several state initiatives to increase the number of containers shipped from Hampton Roads. In 2008, the Port of Virginia mimicked the concept of the inland port when it started the "64 Express" to move containers westward by barge to Richmond. Barging containers on the James River bypassed the traffic congestion on I-64, and provided access to the CSX rail line.

The Code of Virginia gives the Virginia Port Authority broad responsibility for increasing trade:10

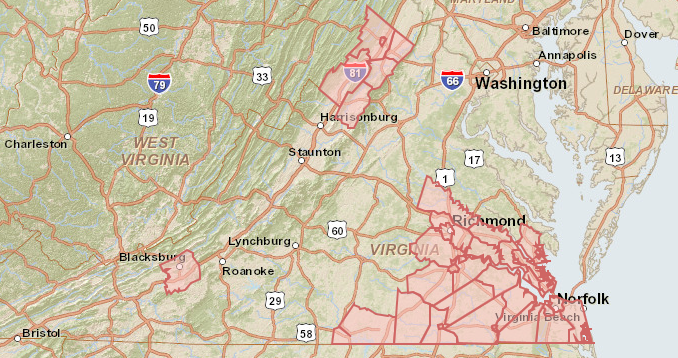

the Port of Virginia Economic and Infrastructure Development Zone includes areas west of the Blue Ridge

Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership, Port of Virginia Economic and Infrastructure Development Zone

In 2012, Governor McDonnell obtained General Assembly endorsement of new incentive programs to spur economic development related to the Port of Virginia. Companies locating within the Port of Virginia Economic and Infrastructure Development Zone, involved in maritime commerce through the port (including warehousing or transporting goods exported and imported through the Port of Virginia) and creating at least 25 new permanent full-time positions, qualify for one-time state grants worth $1,000-$3,000 for each new employee. The boundaries of the special zone include counties/cities near Hampton Roads and the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) in the Shenandoah Valley - plus Montgomery County.11

Including Montgomery County in the zone was intended to attract international partners to open/expand offices near Virginia Tech, or spur domestic research and development (R&D) spin off companies to focus on exporting through the port. Pulaski County already hosted the Virginia TradePort - International Port of Entry #1412 and Foreign Trade Zone #238 - at the New River Valley Airport in Dublin, with on-site Customs and Border Protection personnel to streamline the process for collecting import duties.12

the Commonwealth of Virginia is pursuing construction of a new intermodal transfer facility near Roanoke,

to increase light manufacturing and warehousing/trucking operations in that region

Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership, Port of Virginia Economic and Infrastructure Development Zone

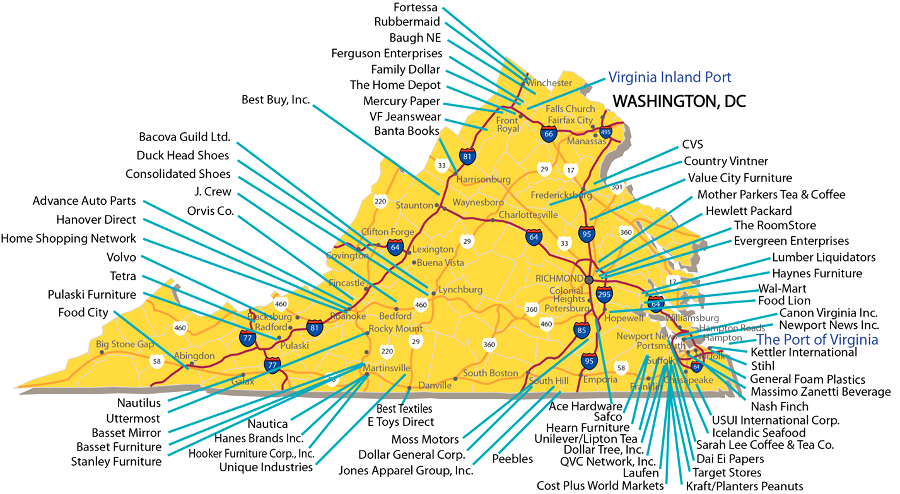

State investment in the Port of Virginia is part of an overall plan to stimulate economic activity across the state, not just in the Hampton Roads area, by emphasizing Virginia's advantages for "global logistics." Virginia is centrally located on the East Coast within a day's drive of 40% of the US population, and 55% of the population lives within 750 miles.

The three terminals of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Port Newark and Elizabeth-Port Authority Marine Terminal in New Jersey and Howland Hook Marine Terminal on Staten Island, are the busiest on the East Coast. For years until it was raised, the Bayonne Bridge limited the height of containers stacked on container ships. The enlarged Panama Canal opened in 2016, a year before the roadway on the Bayonne Bridge was elevated, allowing the Port of Virginia to advertise:13

The Virginia Economic Development Partnership, a state agency, has focused on creating distribution centers to warehouse and transport products moving through the Port of Virginia. Governor McDonnell noted in a 2012 interview how rural areas, far from saltwater, are expected to see a positive return on the state's investment in port facilities:14

Post-Panamax ships are wider and longer, carrying more containers and requiring deeper channels

Source: US Department of Transportation "Fast Lane" blog, Expedited review of port projects to speed jobs, economic growth (July 26, 2012)

distribution centers employ Virginia workers across the state

Source: Virginia Port Authority Powerpoint, The Port of Richmond, Richmond's Future

Most distribution centers are located along all major highways, including sites with no rail access. Backcountry.com, an internet retailer selling sporting goods from its base in Utah, opened its East Coast distribution center in Christiansburg in 2012 so it could ship products quickly, via United Parcel Service, up and down the I-81 corridor.15

Thanks to port and rail connections, new distribution centers are concentrated in Hampton Roads, Richmond, and the northern Shenandoah Valley. The City of Suffolk is the focal point for new distribution centers in Hampton Roads, due to the relatively low cost of land there. Green Mountain Coffee Roasters (which packages imported coffee for single-serve Keurig brewing machines) located there in 2011. In 2013, Lipton Tea expanded its Suffolk operation, which imports tea through the port and produces most of the tea bags sold in the US.16

In 2012, Amazon opened distribution centers in Chesterfield and Dinwiddie counties, with promises to hire over 1,300 people. Business leaders in the Richmond area have identified shipping and distribution as a major regional growth opportunity, starting with expansion of the Port of Richmond into a second inland port, equivalent to the one in Warren County that has resulted in 8 million square feet of storage for 39 companies and creating 8,000 jobs.17

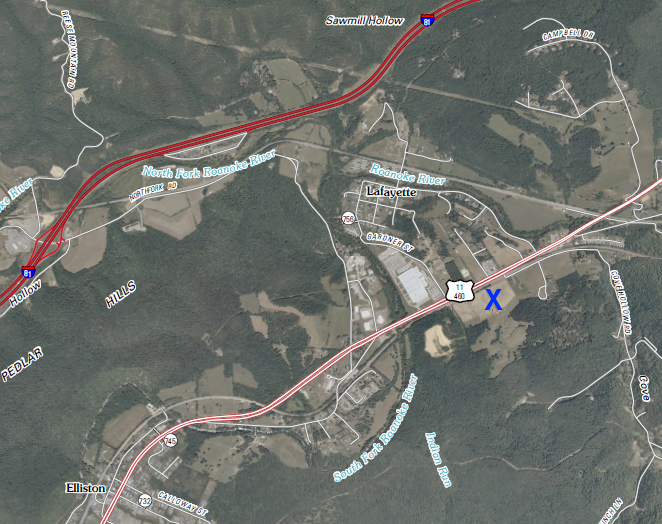

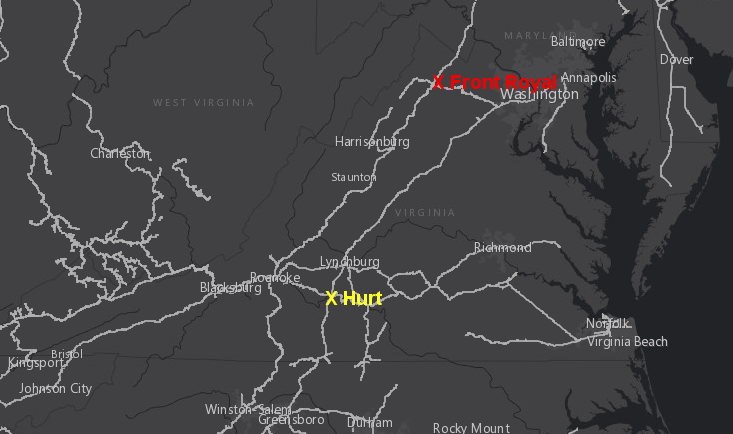

Norfolk Southern's proposed intermodal terminal at Elliston (blue "x") would link I-81 truck traffic with rail traffic on the Heartland Corridor

Source: Norfolk Southern, Intermodal System Map

Barging freight to Richmond, and transporting containers to the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) in Warren County near Front Royal, was part of the state's plan to expand the road/rail network that transports 60% of goods imported through the Port of Virginia to destinations outside Virginia. Creating another inland port west of Lynchburg would also increase rail traffic from Norfolk/Portsmouth.

The first proposal for another inland port failed. In 2006, Norfolk Southern planned for construction of a $36 million Roanoke intermodal transfer station in Montgomery County near Roanoke. Norfolk Southern chose a specific site at Elliston near the Roanoke River. The railroad thought it could overcome strong opposition from Montgomery County that the chosen location was not planned or zoned for industrial use.

The Roanoke intermodal facility was projected to be a southern equivalent to the inland port at Front Royal. It would facilitate transfer of containerized cargo from Norfolk Southern railroad to trucks traveling I-81 south into Tennessee and I-77 into West Virginia and North Carolina. In the reverse direction, the terminal was expected to help the Port of Virginia compete with the ports at Wilmington/Charleston/Savannah. At the intermodal transfer station, containers would be taken off trucks that might otherwise drive to Carolina/Georgia ports, and those containers would travel instead on trains to Norfolk/Portsmouth.

The Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation committed to paying 70% of the terminal's cost in 2008, if the Norfolk Southern railroad diverted 150,000 containers annually from congested highways (especially I-81).

Montgomery County carried its objections all the way to the Supreme Court of Virginia, since Article X Section 10 of the state constitution prohibits funding "internal improvements" except public roads and public parks. That provision dates back to 1869, after the state nearly bankrupted itself by over-investing in turnpikes, canals, and railroads prior to the Civil War.

A final Supreme Court of Virginia decision in 2011 authorized the state funding. The court decision noted that the same article in the Constitution of Virginia allows "loans to finance industrial development and industrial expansion."18

State officials anticipated that an intermodal terminal in Montgomery County would generate local jobs by attracting warehousing and distribution centers, manufacturers, and logistics and transportation-related companies. Candidates for economic development recruitment included automobile/truck parts manufacturers and suppliers and producers of light weight, high quality commodities for packaged food and furniture.

Building the enhanced transportation capacity at Elliston would allow economic development officials in the Roanoke region to provide a different response, when asked by companies about the closest location for transferring containers between trucks/trains. The standard "go to Greensboro, North Carolina..." response would enhance economic development in North Carolina, not Virginia.19

The Elliston project was delayed by both the 2008 economic recession and lawsuits. In the end, no construction ever began at that Roanoke intermodal facility.

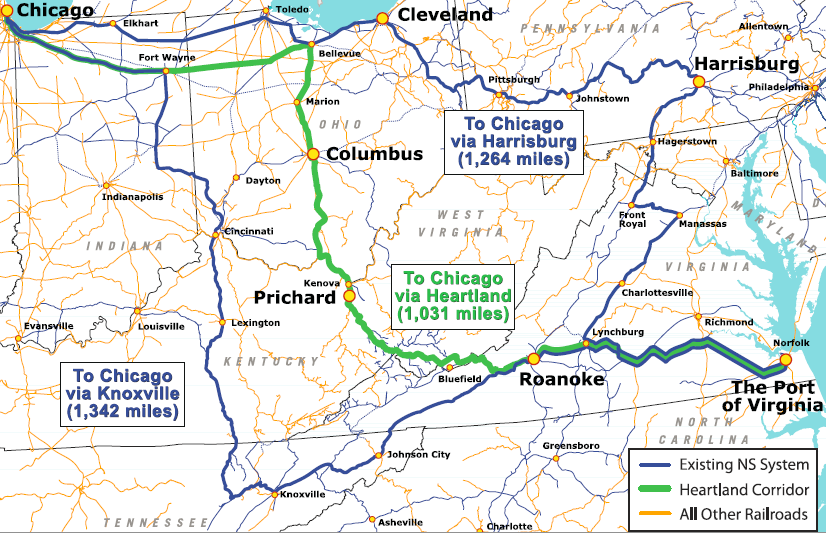

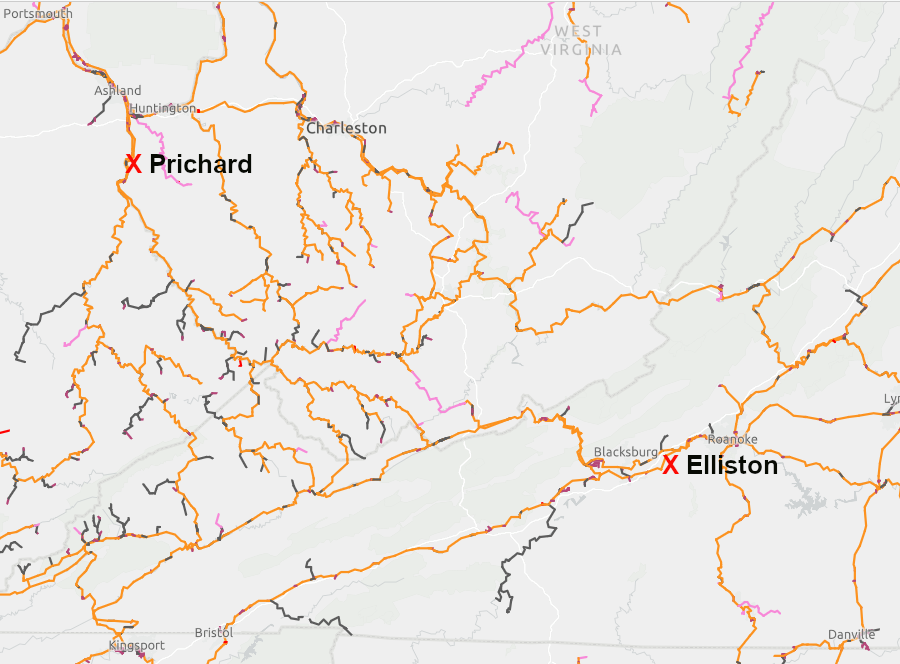

The Roanoke intermodal terminal at Elliston was planned as part of the much-larger Heartland Corridor project, which cut a day off the time required for Norfolk Southern to ship containers from Norfolk to Columbus (Ohio) and Chicago. Norfolk Southern, with state and Federal financial support, altered century-old tunnels to allow trains to carry double-stacked containers through tunnels west of Roanoke and down the New River into West Virginia and Ohio.20

West Virginia developed an inland port as part of the Heartland Project, but it failed. The West Virginia Public Port Authority invested $32 million to establish the Heartland Intermodal Gateway at Prichard. Norfolk Southern planned for at least 15,000 containers to be transferred annually between railcars and trucks, but business never reached 1,000 containers per year. In 2022, the facility was transferred to the Wayne County Commission so local government might find a way to use the 65 acres for economic development.21

route of Heartland Corridor, $290 million transformation of old coal hauling route to facilitate shipping double-stack containers by rail from Norfolk to Chicago

Source: Appalachian Regional Commission, The Heartland Corridor: Opening New Access to Global Opportunity

the proposed intermodal facility at Elliston was never built, and the Heartland Intermodal Gateway at Prichard failed

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the empty Heartland Intermodal Gateway at Prichard

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

As an alternative to the Elliston terminal proposal, Pittsylvania County officials proposed a second inland port at the town of Hurt. They partnered with the towns of Hurt and Altavista, plus the city of Danville, to form the Staunton River Regional Industrial Facility Authority.

The proposal, announced in 2016, was to convert the old Klopman Mills textile facility into an equivalent of the inland port at Front Royal with an industrial park. 50 acres would be dedicated to transportation infrastructure, and an additional 750 acres could be developed for warehouses and even manufacturing plants. Norfolk Southern would provide the rail connection to cargo terminals at Norfolk and Portsmouth.

The Hurt proposal led to no action. Later proposals in the General Assembly for a state study of a new inland port on Route 58 near Danville or near Roanoke were not approved by the legislature.22

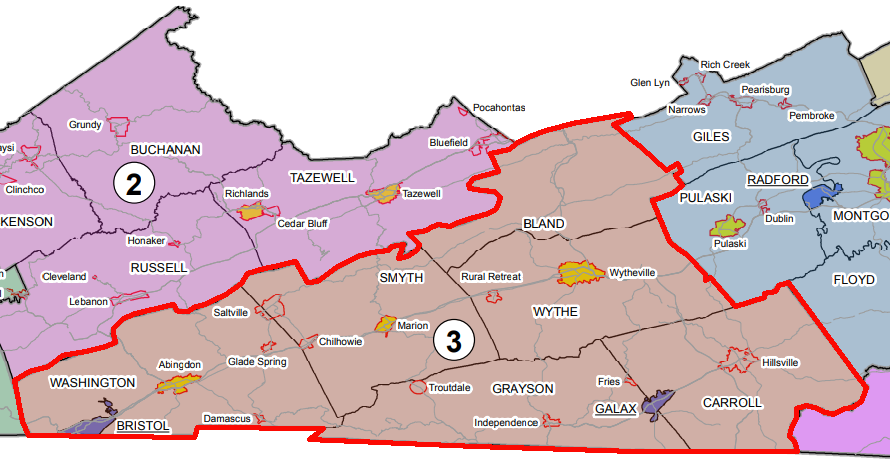

The 2022 budget finally proposed state-funded studies for creating another inland port in Southwest Virginia (Mount Rogers Planning District) or the Lynchburg region (Central Virginia Planning District). The railyard itself would generate few jobs; the Virginia Inland Port in Warren County has only 13 employees. However, distribution centers at inland ports spur economic development. About 30 years after construction of the Virginia Inland Port, nearly $1 billion was invested in constructing warehouses that supported 8,500 jobs near Front Royal.

The planning assumed that a new inland port would have to process 20,000 freight transfers per year, less than the 31,000 lifts in 2021 at the existing Virginia Inland Port. The demand for an inland port would be driven by shippers who wanted lower freight shipping costs, and were willing to accept the slower service from train vs. truck delivery.

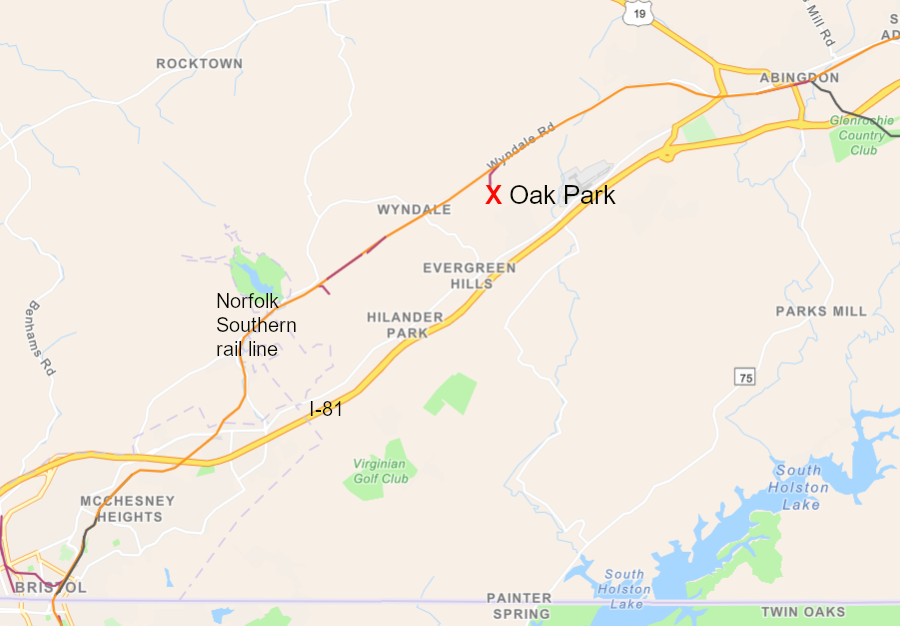

The study concluded that the size of the market around the Central Virginia Planning District did not justify a second inland port. In addition, the area was within 250 miles of Hampton Roads so the savings from long-haul rail traffic did not offset the slower travel time. However, there was potential in the Mount Rogers Planning District. Bristol was 400 miles from Hampton Roads, while Wytheville was 350 miles away. Faster travel times on Interstate 81 also increased the size of the market accessible from the Mount Rogers Planning District.

Southwest Virginia officials proposed specific sites in Washington and Wythe counties. The Industrial Development Authority in Washington County offered to donate the land at an industrial park, the Oak Park Oak Park Center for Business and Industry. The local state senator said:23

in 2023, Oak Park in Washington County was proposed as a site for a new inland port

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

By 2022, Richmond had a barge service from Norfolk; it served as a version of an inland port that reduced rail/truck congestion in Hampton Roads. South Carolina had two inland ports and Georgia had three, including a deal with CSX to use a railyard at Rocky Mount, North Carolina to funnel traffic to the deepwater ports in Georgia at Savannah and Brunswick. Canada was creating an inland port at Winnipeg, Manitoba, for traffic going west via the port at Vancouver or east via the port at Montreal.

Whether Danville, Hurt, Roanoke, Lynchburg, or Bristol was the best location for another inland port was not a decision driven by neutral analysis. As noted by the editor of Cardinal News when the 2022 budget proposal was being considered by the governor:24

the town of Hurt in Pittsylvania County was considered for Virginia's second inland port, comparable to the one in Front Royal

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In September 2023, the General Assembly appropriated $10 million for engineering and design work of an inland port in the Mount Rogers Planning District.

the General Assembly allocated funding in 2023 to design a second inland port in the Mount Rogers Planning District (Planning District 3)

Source: Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development, Commonwealth of Virginia: Counties, Cities, Towns, and Planning District Commissions

Locating the port in Southwest Virginia disappointed officials in the Bedford, Campbell, and Lynchburg region. A consolation prize was a directive by the General Assembly for the Department of Rail and Public Transportation and the Virginia Economic Development Partnership to evaluate rail-centric economic development opportunities in that area.

The General Assembly included $2.5 million funding in the FY24-26 budget for additional planning but no money for actual construction, estimated to be at least an additional $45 million. The second inland port might over time equal the economic impact of the inland port near Front Royal and generate 8,500 jobs. The second port might generate just 1,000 jobs, comparable to the facility in Dillon, South Carolina.

The Virginia Port Authority said in its last 2024 update to the General Assembly that it was resizing the project to minimize land excavation costs, and proposing to build infrastructure in phases. The new planning approach considered creating interim rail service capacity, building less track and a mainline connection that would rely upon shorter trains until demand increased.

At whatever size, the effect of an inland port would be significant in Southwest Virginia. Since 1990, the largest job creation projects in the region had been call centers near Bristol and in Dickenson County that promised 550 jobs each. As described in Cardinal News:25

The existing inland port facility at Front Royal completed upgrades in 2024. Three new rail sidings were added, and four rubber-tire gantry cranes were transferred to the site from Norfolk. The improvements increased terminal capacity by nearly 40%.26

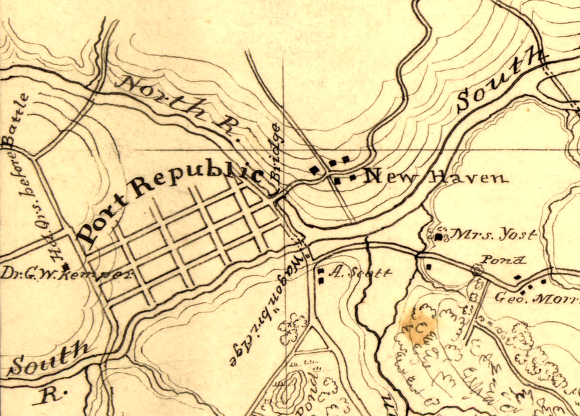

Port Republic, where the North, Middle, and South rivers merge to form the South Fork of the Shenandoah River, reflects Virginia's dependence on water-based transportation even far inland from ocean-going ports

Source: Library of Congress, Topographic map of the battle-field of Port Republic, Virginia, June 9, 1862