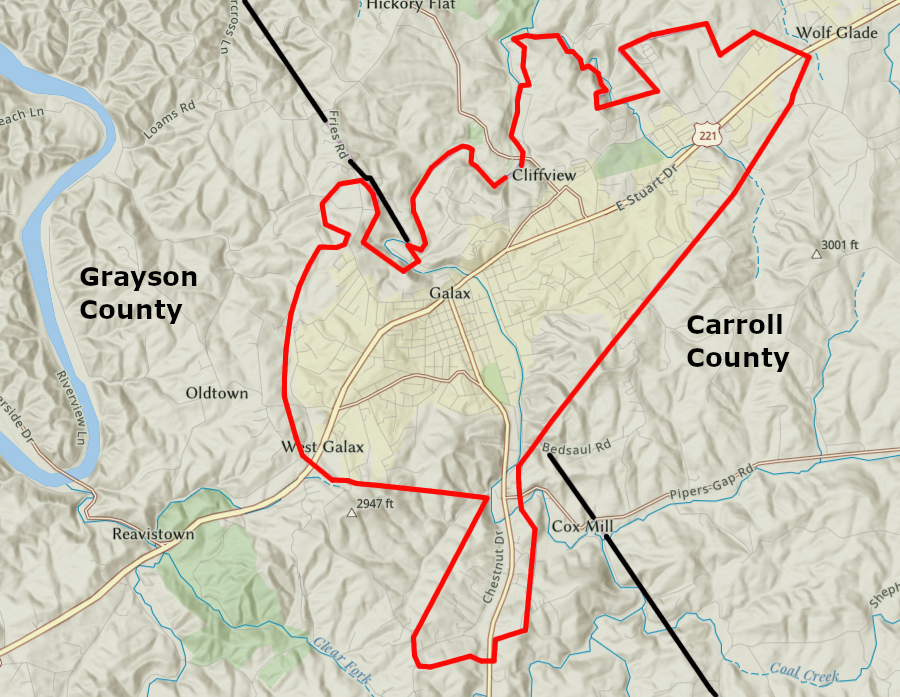

Galax is an independent city, separate from Grayson and Carroll counties

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

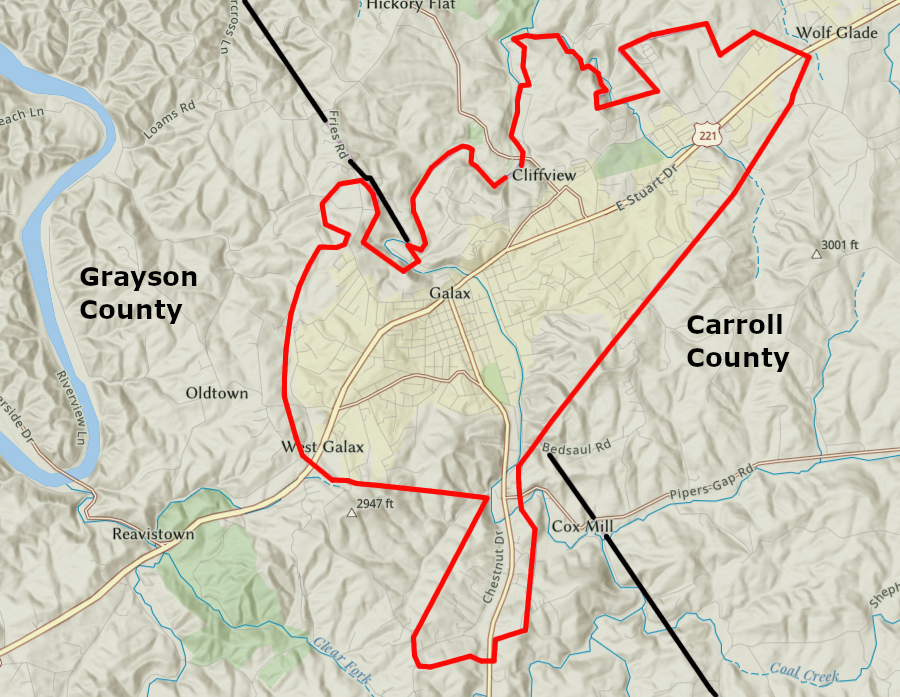

Galax is an independent city, separate from Grayson and Carroll counties

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The first attemps to create a towns in Virginia was Jamestown. There were royal mandates for over 100 years to mandate the creation of additional towns, settlements with many housing units in contrast to scattered farms, but those efforts failed.

After Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, colonial officials consciously sought to change the pattern of development in Tidewater. Ships were loading tobacco at the wharves of major plantations where assessment of colonial fees could be evaded. London officials decided that Virginia should develop towns with markets, specialists such as blacksmiths, and taverns that resembled the towns in England - and that such towns should be designated ports where all shipping to and from England could be monitored and taxed.

Royal orders to create towns were sent to the governors of Virginia. In response, the General Assembly passed legislation in 1680, 1691, and 1705 mandating the establishment of towns. The 1680 orders to Governor Culpeper required creation of one market town and four port towns on the James, York, Rappahannock, and Potomac rivers. Instead, the General Assembly passed "An Act for Cohabitation and Encouragement of Trade and Manufacture" and directed that each of the 20 counties create a town on 50 acres, with all exports and imports to pass through those 20 towns.

The English shipping industry, which operated many ships with captains in order to visit the scattered wharves, arranged for that act to be cancelled in London. In 1691 Governor Francis Nicholson tried again, with the Generals Assembly mandating that 15 of the 20 required towns be for processing imports/exports and for five to be market towns.

|That effort was also abandoned within three years. The few people in Virginia with sufficient wealth to build new houses were planters. They preferred to add new structures at their plantations rather than build a town which was isolated from the plantation's wharf.

In 1705, Governor Nott was directed to have two towns created on the Eastern Shore and three on the four great rivers east of the Chesapeake Bay. The directions did not specify which rivers should have towns. In response, the General Assembly passed "An Act for Establishing Ports and Towns" and proposed 15 towns.1

In the end, towns developed where there was an economic justification for their existence. The General Assembly has managed the creation of urban centers since 1680, but the development of those centers into modern concentrations of people has depended upon non-political reasons.

After World War I, the Alexandria County (renamed Arlington County in 1920) was the first in Virginia to have sufficient population density for local officials to provide public services equivalent to towns and cities. The Supreme Court of Appeals ruled in 1922 that towns could not be created in Arlington County, and its territory could not be annexed by the adjacent City of Alexandria. In essence, Arlington County was to be treated as an independent city, and it was the first county in the United States to adopt the County Manager form of government.2

Today, Virginia cities are totally separate governments from counties, unlike the other 49 states - except for Baltimore, Maryland, St. Louis, Missouri, and Carson City, Nevada. City residents pay taxes to city governments and vote for city officials. County residents pay taxes to a separate county government and vote for a separate set of county officials. City residents resolve legal disputes in separate courts from county residents. Cities and counties have separate land use and transportation plans, and in almost every case separate school systems.

Over the years, 45 independent cities have been created in Virginia. The last to be created were Manassas, Manassas Park, and Poquoson in 1975, when they converted their status from towns to cities. The number of jurisdictions designated as cities has been reduced over time by consolidations of cities/counties and by reversion of South Boston, Clifton Forge, and Bedford from "city" to "town" status.

In 2025 there were 38 remaining independent cities. Martinsville was the most rent to seek court approval to be redesignated as a town, which would make it part of Henry County with shared constitutional officers and a shared school system. City officials dropped that effort when residents in both jurisdictions objected.

The constitutions of Virginia have always distinguished cities from counties. The 1776 constitution authorized election of two people from each county to the new House of Delegates which replaced the colonial House of Burgesses, and authorized one person to serve in the House of Delegates for the city of Williamsburg and the borough of Norfolk. So long as those two or future cities/boroughs had sufficient population, they were authorized to elect separate members of the House of Delegates:3

Though the towns had additional representation in the state legislature, they were not separate government entities from the counties. They shared a court system, along with a sheriff.

The 1830 state constitution provided authorities for "each county, city, town or borough." That constitution made no distinction between the categories of county, city, town or borough except for representation in the House of Delegates. In both the 1830 and 1776 state constitutions, each county was authorized two delegates. In the 1830 state constitution the cities of Williamsburg and Richmond, the borough of Norfolk, and the town of Petersburg were each permitted to elect one member of the House of Delegates.

Williamsburg obtained a city charter in 1722 when Virginia was still a colony. The General Assembly granted a charter to the Borough of Norfolk in 1736, and the designation as a "borough" was never applied to another jurisdiction afterwards. Richmond was incorporated in 1782 as the first "city" after Virginia became an independent state.4

The term "borough" was dropped from the 1851 state constitution. Norfolk and Petersburg were listed as a city in that constitution, along with Williamsburg and Richmond. The town of Lynchburg was authorized to elect a person to the House of Delegates, if Campbell County voters chose to reduce their right to elect two delegates to just one and let Lynchburg elect the other.

The 1851 constitution required creation of wards for elections within every city or town where the *white* population exceeded five thousand. That created a population threshold that would be used in 1902 as the minimum for chartering an independent city. Alexandria, which was authorized in 1749 and had been incorporated by the legislature as a "town" in 1779, was incorporated as a "city" in 1852.

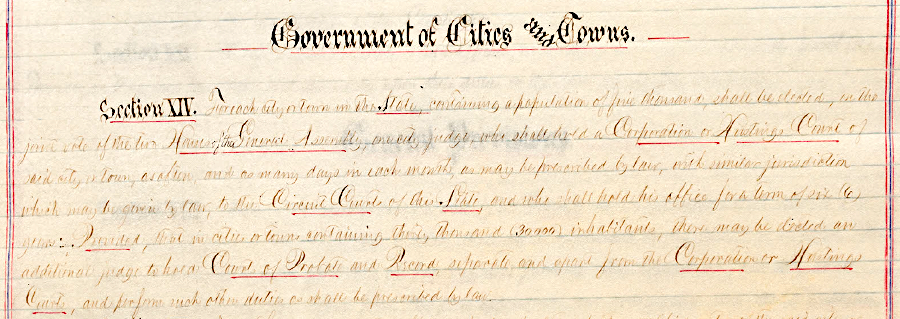

The legislature's power to grant authority to the courts in cities and other municipal corporations was broad:5

The 1870 state constitution is considered to be the turning point when cities became independent from counties.

That constitution was adopted during Reconstruction after the Civil War. included a new section for "Government of Cities and Towns." Portsmouth was listed as a city, based on 1858 legislation. According to the 1870 constitution, the General Assembly had to elect a corporation or hustings court judge for every city or town with 5,000 residents, and the 1870 constitution no longer specified counting only white residents to reach the 5,000 threshold.

The General Assembly was empowered by the 1870 constitution to elect a second circuit court judge for cities with at least 30,000 people. A single court clerk was to be elected for the corporation (or hustings) court and the circuit court, except cities with 30,000 people were to elect a separate clerk for the circuit court.

Cities and towns with at least 5,000 residents also were directed to elect a mayor, commonwealth attorney, city sergeant, treasurer, and commissioner of the revenue.

Specific requirements for county officials was also provided in the 1870 constitution, and counties with at least 15,000 people also had to elect one superintendent of the poor. The first Tuesday after the first Monday in November was established as the election day for county officials, while the election date for city and town officials was set as the fourth Thursday in May.

The new state Board of Education was required to appoint a superintendent of schools in counties. The board could appoint a second superintendent of schools for counties with at least 30,000 people, and counties with less than 8,000 inhabitants could share that position with the neighbors. No separate superintendent of schools was specified for cities or towns.6

The evolution of totally-independent cities occurred after the Civil War. They were chartered by special acts of the General Assembly and all boundary changes between cities and counties required action by the state legislature. That lasted until adoption of a new constitution in 1902, in which the circuit courts were given authority to create an independent city.

The convention in 1868, which wrote the constitution implemented in 1870, directed each county to establish at least three townships with elections for local officials:7

The creation of townships reflected the influence of northern concepts at the constitutional convention, but also matched the vision of Thomas Jefferson. He had wanted to shift power from the planter-dominated county courts to smaller units of government modelled on the New England township, but the 1776 and 1830 constitutions failed to follow his recommendations.

In areas with a majority-black population, if local township officials were elected then some black men might end up with political power over whites. Through an 1874 constitutional amendment the township concept was replaced with magisterial districts. Each county was still required to be subdivided into at least three magisterial districts, but fewer officials were to be elected in individual districts. After 1874, each magisterial district elected just one supervisor, three justices of the peace, one constable, and one overseer of the poor.

The challenge of providing more local control in densely populated areas was addressed by chartering cities and towns. In 1876, the state constitution was amended to add this clause:8

Towns/cities with at least 5,000 people were authorized to have local corporation or hustings courts, and they would share the circuit court with the counties within their specific judicial district.

Between 1870-1902, especially after the defeat of the Readjusters in 1883, the white political elites who controlled Virginia created de jure segregation by passing "Jim Crow" laws. The new cities created after approval of the 1870 state constitution were not located in areas where a white minority might lose political control to a black majority. That may have been a factor in the willingness of the state legislature to transfer authority to units of government smaller than counties. After 1892, a town could also incorporate as a city by petition to the circuit court.

The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals started to adopt the Dillon Rule in 1882. Under that interpretation of state constitutions, the legislature had to clearly grant a power to a city/town; otherwise, it was not legal for the local government to provide a municipal service. The 1896 case City of Winchester v. Redmond made clear that Virginia courts would assume strict construction of state power rather than home rule for localities.

Virginia judges limited the powers granted to municipal corporations by the General Assembly. Each charter, with its different language, was at risk of judicial interpretation that blocked a program which legislators and local officials thought they had authorized. The 1902 constitution enabled independent cities to operate under a general law, reducing the risk that different city charters would be interpreted differently and simplifying the understanding of what basic government powers had been granted to all cities.

the 1870 constitution authorized cities/towns with at least 5,000 people to create their own corporation or hustings court

Source: Library of Virginia, Constitution, 1868

The 1902 state constitution identified 18 cities - Alexandria, Bristol, Buena Vista, Charlottesville, Danville, Fredericksburg, Lynchburg, Manchester, Newport News, Norfolk, Petersburg, Portsmouth, Radford, Richmond, Roanoke, Staunton, Williamsburg, and Winchester. After 1902 came the creation of Hampton (1908), Suffolk (1910), Harrisonburg (1916), Hopewell (1916), South Norfolk (1921), Martinsville (1928), Waynesboro (1948), Colonial Heights (1948), Falls Church (1948), Virginia Beach (1952), Warwick (1952), Covington (1952), Galax (1953), Norton (1954), South Boston (1960), Fairfax (1961), Franklin (1961), Chesapeake (1963), Lexington (1966), Salem (1968), Emporia (1968), Bedford (1968), Nansemond (1972), Manassas (1975), Manassas Park (1975), and Poquoson (1975).

The City of Alleghany was authorized by the General Assembly in 1991, if approved by the voters of Alleghany County and the City of Clifton Forge. Both jurisdictions rejected consolidation in 1992, so the 45th authorized independent city in Virginia was never created.

Cities had been created through special acts of the General Assembly until the 1902 constitution banned use of the special act process for that purpose. The ban on special legislation by the General Assembly was designed to prevent the state legislators from micro-managing issues in individual cities and towns.

The 1902 constitution created a general law process by which a circuit court could create a new city, rather than rely upon the General Assembly to approve an individual charter for each new city. In 1904, the General Assembly created a standard process by which cities could annex territory from adjacent counties and expand the size of a city. By defining criteria for creating "second class" and "first class" cities and modifying their boundaries, the General Assembly transferred workload from the legislative to the judicial branch.9

The need for city-level government in Virginia had become clear by 1902. The 1900 Census documented that 20% of the population were concentrated in urban centers, and 10% lived in places with at least 25,000 people.

Why the General Assembly created a unique political structure, with independent cities separate from counties, is not clear. According to one scholar:10

One possibility is that the delegates to the 1901-1902 constitutional convention were reacting to systemic corruption in the election process. The members of the convention were split between members of the "machine" managed by Senator Thomas Staples Martin vs. independent Democrats. Both factions used voter fraud to win elections despite passage of the Walton Act in 1894 requiring electoral officials to provide a standardized ballot to voters, and neither faction had clear control over the 1901-02 convention.

The Dillon Rule assumed that state officials would be less corrupt than local officials, and local authority should be limited. Perhaps in response to the perspective that local government would be more corrupt than state government, the 1902 constitution totally eliminated a key layer of local government, the county courts.

Judges for the county courts were appointed by the legislature, and those judges then appointed local officials such as the sheriff and Commonwealth's Attorney. Through the selection of county court judges, members of the General Assembly had the potential to create a "courthouse ring" of judges and other local officials who owed their jobs to the legislators elected from that county. In too many cases, the county court judges and local officials which they appointed were willing to commit voter fraud in order to help the legislators win an election. New legislators might arrange for the General Assembly to appoint new judges, and new judges might appoint new justices of the peace, constables, etc.

To replace the county courts, the 1902 constitution expanded the number of circuit courts from the 16 authorized in the 1870 constitution to 24 circuit courts. The 1901-1902 constitutional convention rejected a proposal to have circuit court judges elected, so the new constitution did not prevent the creation of a courthouse ring centered around 24 circuit court judges. The election of a circuit court judge involved a larger number of legislators than the selection of county courts judges, so the potential for a local courthouse ring was reduced. Instead, the stage was set for a statewide political machine to control elections, as Harry Byrd demonstrated between the 1920s-1960's.

In 1901 there were corporation or hustings courts in cities and towns with at least 5,000 residents, creating a parallel to the county courts. The 1902 constitution did not eliminate the city courts that had been authorized in the 1870 state constitution. However, In contrast to cities, towns do not have courts, constitutional officers, or electoral boards.

Creating independent cities, separate from the counties, may have been done to define the jurisdiction of the city courts. Defining in city as "independent" made clear that city courts had no authority in the counties. Outside of city boundaries, the justices of the peace and the 24 circuit courts managed judicial responsibilities.11

The 1902 state constitution established two categories of independent cities. Those with more than 10,000 people were defined as "first class," while those with 5,000–10,000 people were "second class." The key difference was that a separate Circuit Court was not created for just the second class cities, and they had to share the court with the adjacent county.

The distinction between the two classes of cities was dropped when the state constitution was revised in 1971. At the time, there were 14 second class cities. Cities that transitioned since 1902 from second class to first class continued to share the circuit court with the county, except for criminal cases. Also, the state legislature had previously created separate circuit courts for Bristol, Colonial Heights, Fredericksburg, Martinsville, Salem and Suffolk; those courts separate from counties continued in operation after 1971.

As a Dillon Rule state, Virginia's local jurisdictions have limited "home rule" powers. Most counties have chosen to leave that issue alone and seek special legislation whenever needing special authority. The greatest opportunity in recent times to grant home rule to counties and equalize the powers with those of independent cities was during the revision of the state constitution in the late 1960's. The counties chose not to take advantage of the opportunity, calculating that they would gain greater control and avoid unwanted responsibilities by requesting special legislation.12

General law changes have also enabled counties to gain some powers once granted to only cities. In 1924, Chesterfield County formalized its creation of a police department because the General Assembly had granted such authority to counties adjoining a city with a population over 125,000. In 2020, the General Assembly significantly expanded the powers of counties to match that of cities, including the authority for a county Board of Supervisors to impose a meals tax without a voter referendum.13

One particular power granted by the state legislature only to chartered cities triggered several counties in southeastern Virginia to convert into independent cities after World War II. City status blocked annexation efforts of an adjacent city. Incorporating as a city enabled Elizabeth City County to block the City of Newport News from annexing land, and kept the City of Norfolk from annexing portions of Princess Anne County.14

The distinctions between county vs. independent city has lost most of their significance since the adoption of the 1971 constitution. While cities and towns were created by special actions of the General Assembly or under general laws establish a procedure for court action, few counties have used the 1985 Uniform Charter Powers Act and sought a county charter specifying special authorities.

Prior to the adoption of a revised state constitution in 1971, Arlington and Fairfax counties obtained special legislation to address the challenges they faced during urbanization. Chesterfield, James City, and Roanoke County received county charters between 1986-1993, but other counties have not bothered.

In 1968, the Subcommittee on Local Government of the Commission on Constitutional Revision recommended Virginia follow Alaska, Massachusetts, and Texas, which had abandoned the Dillon Rule. However, the General Assembly rejected the proposal to include recommended home rule language in the new constitution, so that a:15

By the 1960's, over 50% of Virginia residents lived within urban areas; the distinction between a city such as Falls Church and a suburban county such as Fairfax had largely disappeared. Since 1975, the General Assembly has not created any new cities.

The legislature has limited the ability of existing cities to annex territory from counties, and suburban county governments closely resemble city governments. Some, such as Fairfax and Prince William counties, have established police departments under the control of the county executive. Other suburban counties, including Loudoun County, continue to rely upon the ability of the sheriff and deputies for law enforcement.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Prince William County officials were unhappy with the responsiveness of the state-run Prince William Health District. The General Assembly responded by granting the county the authority to created a locally-run Health Department. However, the cities of Manassas and Manassas Park were reluctant to join the proposed Health Department. The county would make final decisions on the costs of the operation, and the cities would be obligated to provide financing which they could not control.

The willingness of the state legislature to empower the county even before negotiations were completed with the two cities demonstrated that there was little advantage by 2022 in being designated an "independent" city.16