Wastewater Reuse: Eliminating Discharge to "Receiving Waters"

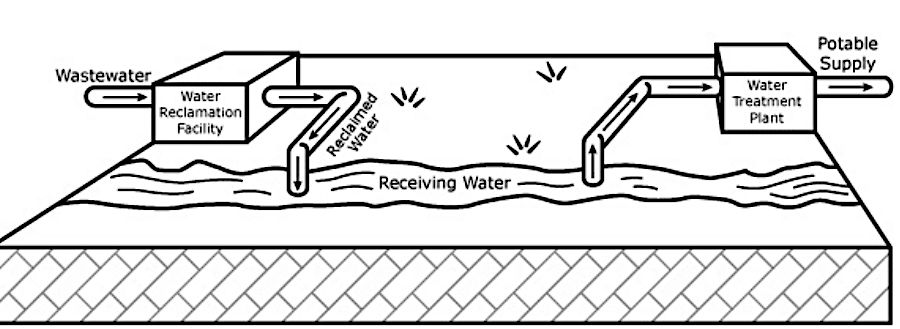

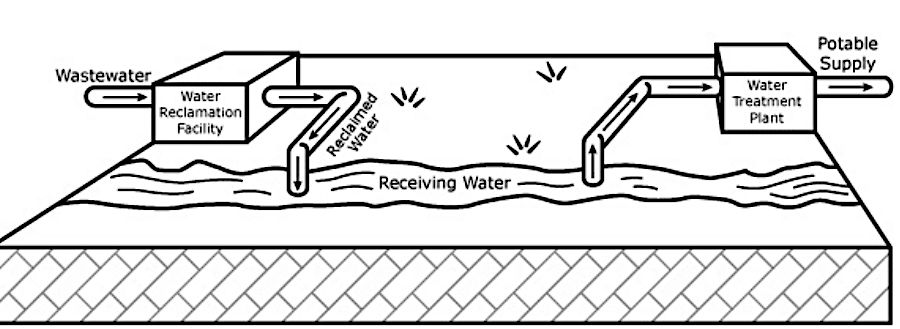

the most common form of wastewater recycling is for a treatment plant to discharge into a stream, then have a drinking water plant use that water downstream

Source: Arizona Department of Water Resources, Reclaimed Water Trends Nationally and Internationally

On the International Space Station, wastewater is recycled and astronauts drink the clean fluid that emerges at the end of the process. It is a toilet-to-tap cycle that recovers 90% of the water brought to the station.

In Virginia, "used" water is re-introduced to the drinking water system typically only after the water has flowed down a river for some distance, or has infiltrated or been injected into groundwater in an Aquifer Storage and Recharge (ASR) process. Most Virginians flush and forget, and are unaware that the water fountain at school and the soda machine at a fast food restaurant are probably providing some recycled sewage from an upstream source.

The technology is readily available to recycle water in Virginia, just as in Texas and on the International Space Station.

Direct reuse, involving a pipeline providing a direct link between the outfall of a wastewater treatment plant and the intake pipe of a drinking water facility, has been implemented in Big Spring, Texas, Cloudcroft, New Mexico, Singapore, and other places where water resources are limited. It is common for treated wastewater discharged into streams to be extracted downstream and used for drinking water in Virginia, but to date no community has faced a water supply shortage that was serious enough to overcome the public's attitude (the "yuck" factor) regarding direct reuse and implementation of a toilet-to-tap operation.1

Three types of water are candidates for reuse:2

- Gray water is untreated household wastewater from bathtubs, showers, lavatory fixtures, wash basins, washing machines and laundry tubs. It does not include wastewater from toilets, urinals, kitchen sinks, dishwashers or laundry from soiled diapers.

- Storm water is precipitation discharged across land to water or through conveyances to one or more waterways. It may include storm water runoff, snow melt runoff, surface runoff and drainage.

- Wastewater is untreated liquid containing domestic sewage and industrial waste. Wastewater comes from residential dwellings, commercial buildings, industrial and manufacturing facilities, and institutions.

Gray water recycling is regulated by the Virginia Department of Health (VDH). The health officials also are responsible for regulating "harvested rainwater" from parking lots and rain barrels. The Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development regulates reuse of water recycled within a building for purposes other than drinking water (i.e., "non-potable uses"). For example, the Virginia Uniform Statewide Building Code allows for water collected on rooftops to be used to flush toilets, but not to be used in drinking fountains.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) regulates both stormwater and wastewater.3

Stormwater recycling can be achieved by Low Impact Development (LID) projects, which recharge groundwater aquifers via swales and rain gardens. In addition to increasing groundwater supplies, such projects divert stormwater away from surface streams. That reduces pollution going into those streams. Retention and diversion of stormwater into the ground can also reduce the volume and speed of peak streamflow, minimizing erosion of sediment within the stream channel.

Until the 1990's, wastewater was traditionally considered as just a waste product like stormwater. They were seen as saturated with unhealthy microorganisms and other pollutants, rather than as a potential resource. Today, industrial facilities and utilities are examining how they can recycle their final product, rather than discharge it directly to "receiving waters" as regulated by the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits required by the Clean Water Act.

Since 2008, Virginia has permitted re-use of wastewater for industrial processes, air conditioning systems, irrigation, and a variety of other uses. The terminology of wastewater treatment reflects the changed attitudes. "Treated sewage" and "effluent" are now called "reclaimed water," and publicly owned treatment works (POTW) may describe themselves as a water factory.4

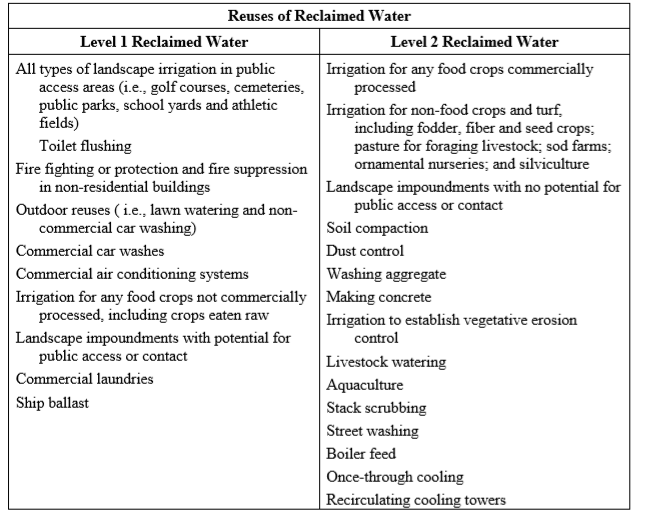

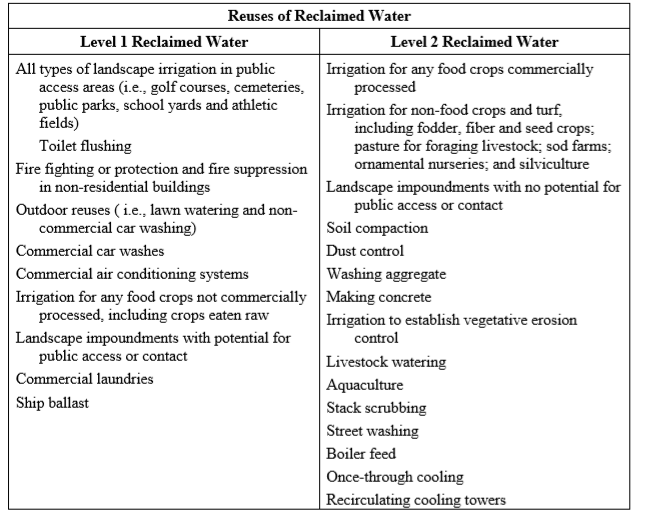

The Department of Environmental Quality defines two levels of treatment required for reuse of municipal and industrial wastewater, based on the types of pollutants in the wastewater and the potential for public contact:5

- Reclaimed water meeting Level 1 is more highly treated and disinfected, and suitable for reuse with potential for public contact. Reclaimed water meeting Level 2 is not as highly treated and disinfected as Level 1 reclaimed water and is suitable for reuses where there is little or no potential for public contact.

the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality allows municipal and industrial wastewater to be treated and reused

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Frequently Asked Questions About Water Reclamation and Reuse

The reduce-reuse-recycle mantra, when applied to wastewater, has both environmental and economic benefits. In most cases, projects for reusing wastewater are designed to reduce pollutants that otherwise would flow into the Chesapeake Bay. In one case, the steady temperature of treated wastewater is used to reduce heating/cooling costs.

For an industrial user or golf course, re-use allows a company to purchase lower-cost water that still meets their requirements, rather than purchase more-expensive water treated to drinking water standards. Drinking water utilities lose customers when potable water is replaced by reclaimed water, but eliminating some irrigation and industrial use can increase a utility's long range capacity to meet future demand as population grows.

For a wastewater utility, re-use allows discharging less total nitrogen and phosphorous. That has the potential of reducing costs to meet limits in a facility's Virginia Pollution Discharge Elimination System (VPDES) permit.

Reuse is not a new concept. In 1976-77, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) tested re-use of wastewater at a rest area on I-81 near Fairfield. Blue dye was added to the treated water, which was then used to flush toilets. About 95% of water used at the rest area was recycled, but potable water was still required for sinks and drinking fountains. Today, Loudoun County's Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility recycles wastewater to flush toilets there, sending some water in a perpetual cycle through that facility.6

The first industrial water reuse project in Virginia was a pilot project by the Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD), implemented in 2002 before the statewide regulations were changed. The HRSD York River Treatment Plant was located next to an oil refinery owned by Amoco near Yorktown. The wastewater treatment plant built a short pipeline underneath a creek and pumped 500,000 gallons a day of treated wastewater to the refinery for use in its operations.

York Wastewater Treatment Plant in York County, site of first industrial re-use of wastewater in Virginia

Source: Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD)

The refinery purchased reclaimed water at 50% of the cost of drinking water. The utility benefitted, because evaporation of the reclaimed water at the refinery into the atmosphere reduced the amount of nitrogen the utility discharged into the Chesapeake Bay. However, the refinery closed in 2010 after Giant Industries purchased it from Amoco, and HRSD lost its customer for reclaimed water. The utility had spent $3 million, some borrowed in a 20-year loan from the Virginia Water Facilities Revolving Fund, to upgrade the York River Treatment Plant so the reclaimed water would meet industrial specifications. The refinery shut down only nine years into the contract.7

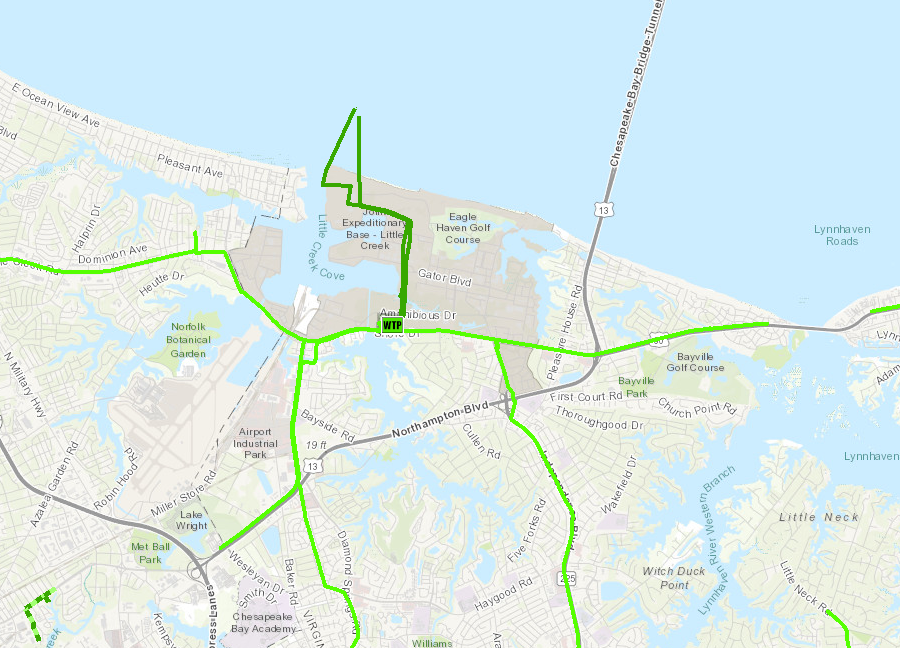

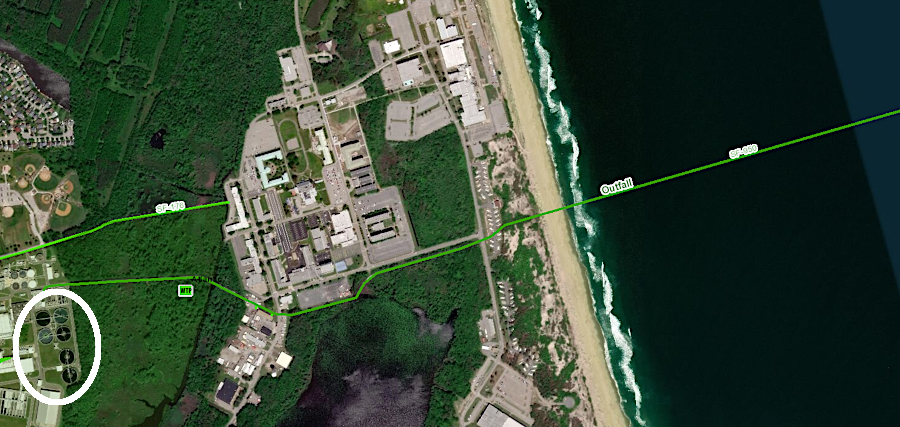

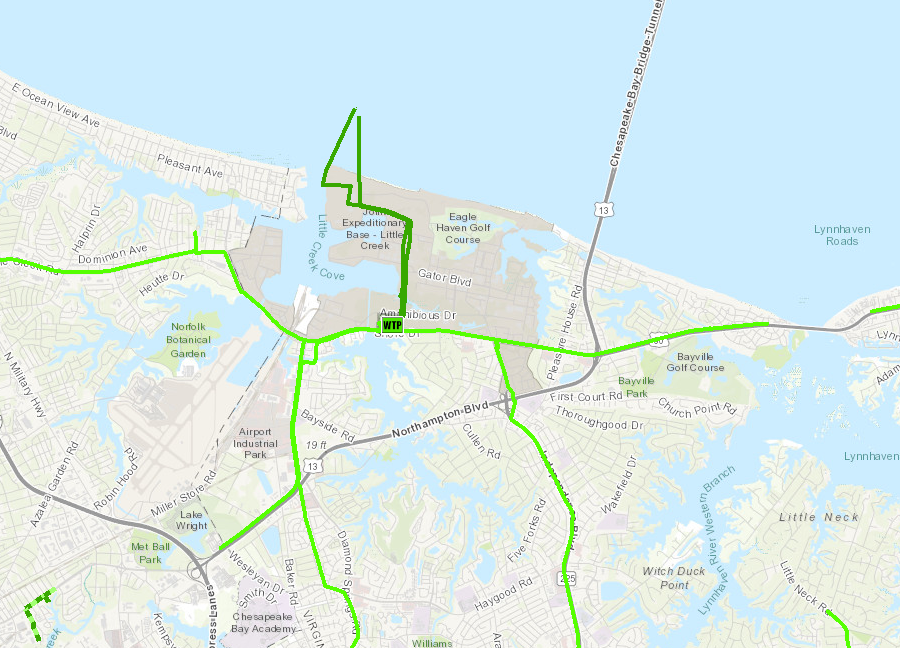

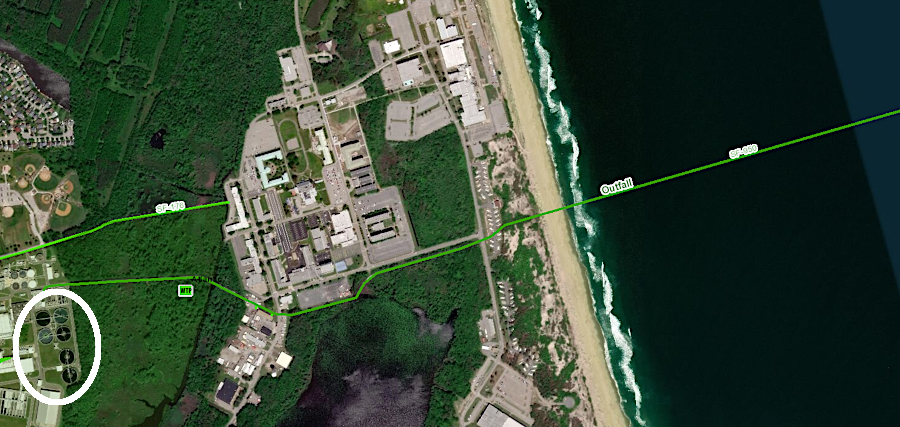

green lines show pipes delivering treated wastewater to oil refinery north of the York River Waste Treatment Plant (WTP) and to outfall on York River

Source: Hampton Roads Sanitation District, Public GIS Viewer

Another wastewater plant in the Hampton Roads Sanitary District, the Virginia Initiative Plant (VIP) at Lamberts Point in Norfolk, targeted potential re-use for irrigation at an adjacent 9-hole public golf course. Additional irrigation pipes were installed at the golf course, which was constructed on top of a closed municipal landfill, allowing use of treated wastewater for irrigation.

The district later purchased the golf course in 2018 in order to expand the Virginia Initiative Plant and allow treated wastewater to be injected into the Potomac Aquifer, as part of the Sustainable Water Initiative for Tomorrow (SWIFT) project. The course was scheduled for closure in 2023.8

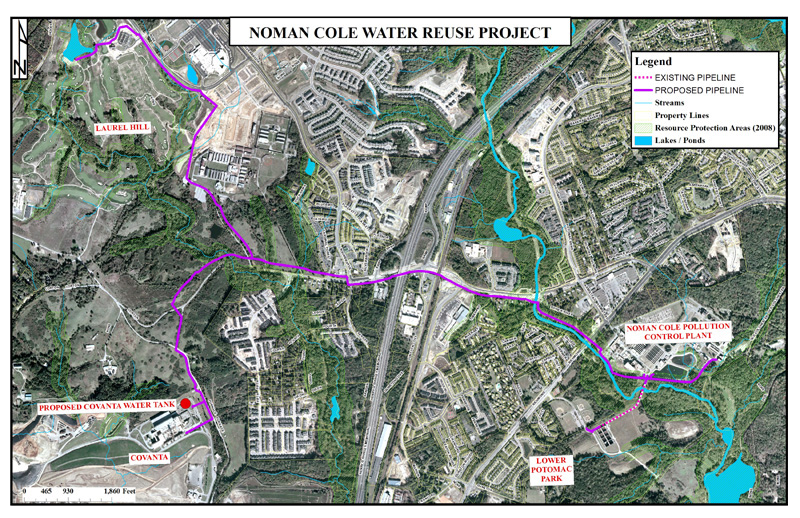

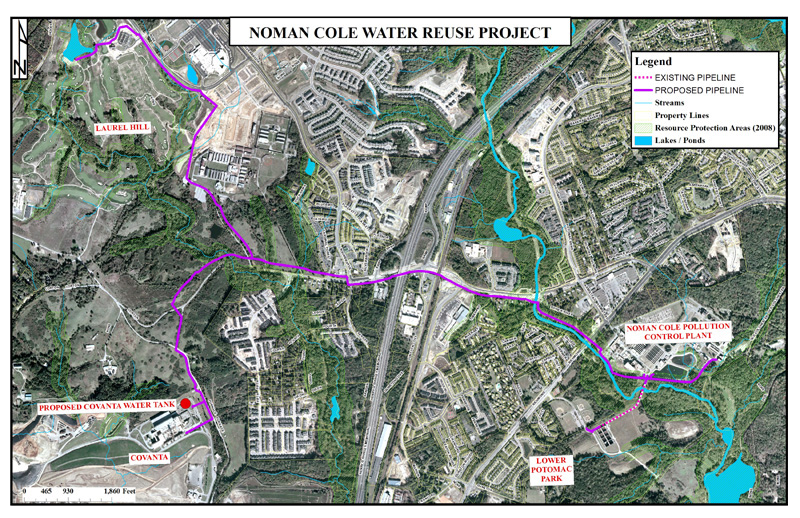

The Keswick Club near Charlottesville uses wastewater from its own facilities for irrigating its golf course, providing a steady supplemental supply to supplement water withdrawn from its lake. In Northern Virginia, the Laurel Hill Golf Course and the baseball field at Lower Potomac Park are irrigated with treated wastewater from the Noman Cole Wastewater Treatment Plant five miles away. If reclaimed water has too much sodium, chloride and bicarbonate residue from the treatment process, gypsum can be added to get the correct water chemistry before irrigating.9

the Virginia Initiative Plant at Lambert's Point (just north of the Norfolk Southern coal piers) supplies treated wastewater for irrigation at the adjacent golf course

Source: GoogleMaps

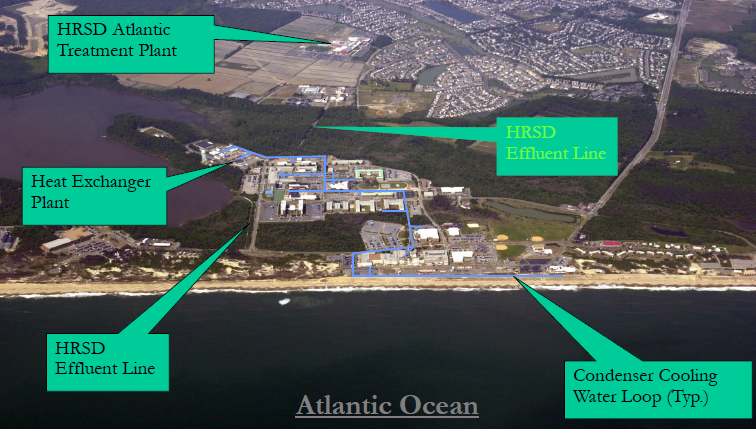

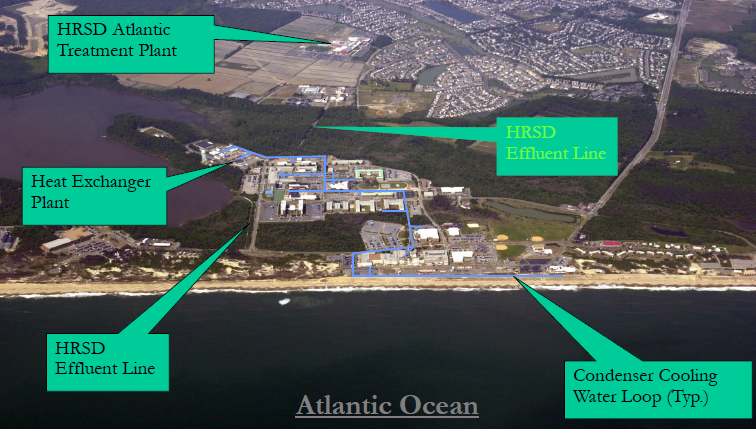

The military has partnered with the Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD) to take advantage of the steady temperature of wastewater discharged from the utility's Atlantic Treatment Plant in Virginia Beach, next to Lake Tecumseh. The treatment plant sends its wastewater north into the Chesapeake Bay. Since 2008, the Naval Air Station (NAS) Oceana - Dam Neck Naval Annex has run 14 million gallons/day of wastewater though a heat exchanger, reducing the annual heating/cooling costs at the military base.

The wastewater was already passing through the base to its discharge point in the Atlantic Ocean. The Department of Defense arranged for a private company to fund and install the new heat exchange system under a $33 million Energy Savings Performance Contract. The military expected to reduce energy costs by more than that amount over the 17-year contract.10

Dam Neck Naval Annex in Virginia Beach uses treated wastewater to increase energy efficiency

Source: 2011 Environment Virginia presentation, Energy Efficiency and Innovation

The Hampton Roads Sanitation District decided to reduce the amount of nitrogen and phosphorous it discharged into the Chesapeake Bay in part by closing the Chesapeake-Elizabeth Treatment Plant. After closure in 2023, wastewater will be diverted to the Virginia Initiative Plant in Norfolk (once expanded onto the adjacent golf course) and the Atlantic Treatment Plant in Virginia Beach. Whatever percentage ends up being treated at the Atlantic Treatment Plant will be discharged into the Atlantic Ocean That will reduce the nutrients which are considered in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) "pollution budget," and help to restore the bay.11

the pipeline carrying wastewater from the Chesapeake-Elizabeth Treatment Plant (dark green) in Virginia Beach carries nutrients into the Chesapeake Bay

Source: Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD), HRSD Public Map

the pipeline carrying wastewater from the Atlantic Treatment Plant (white circle) carries nutrients into the Atlantic Ocean

Source: Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD), HRSD Public Map

In Fairfax County, the Noman Cole Wastewater Treatment Plant on Route 1 in Lorton partnered with the Covanta Fairfax Inc. Resource Recovery Plant waste-to-energy plant on Route 123. The arrangement allows the facility to increase the volume of wastewater it can process without increasing the amount of nitrogen that it discharges into Pohick Creek.12

Source: Fairfax County - Water Reuse Project

In Fauquier County, the Old Dominion Electric Cooperative uses wastewater from the Fauquier County Water and Sanitation Authority's Gordonsville Wastewater Treatment Plant to cool the Marsh Run gas-fired power plant. The wastewater evaporates, reducing the quantity of nitrogen and phosphorous for which the utility must obtain a permit to discharge into the Rappahannock River.

In Loudoun County, Green Energy Partners/Stonewall made a similar arrangement for cooling the gas-fired 750-megawatt power plant near Leesburg. The town committed all of the town's wastewater for industrial reuse at that site:13

- The generating station will use reclaimed municipal waste water from the Town of Leesburg to cool the plant. Putting to use waste water that would normally be diverted to the Potomac River subsequently prevents the discharge of harmful nutrients into the environmentally sensitive Chesapeake Bay watershed. The Stonewall plant will also be a "zero-liquid-discharge" plant, returning no waste water to a treatment facility.

The power plant will build a new pipeline (the "Purple Line") to transport wastewater to the power plant, potentially eliminating all of the town's wastewater discharge (and all nutrients...) to the Potomac River. Leesburg faced an unusual problem - could it generate sufficient wastewater to meet the requirements for the power plant? The town normally produced 4 million gallons/day, though the wastewater treatment plant had sufficient capacity to process 7.5 million gallons/day. The power plant will build a 5-million gallon storage tank, as a reserve.

If needed, Leesburg could purchase potable water from Loudoun Water. Loudoun Water would prefer to sell wastewater from its Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility, but the Stonewall power plant location is too far away.14

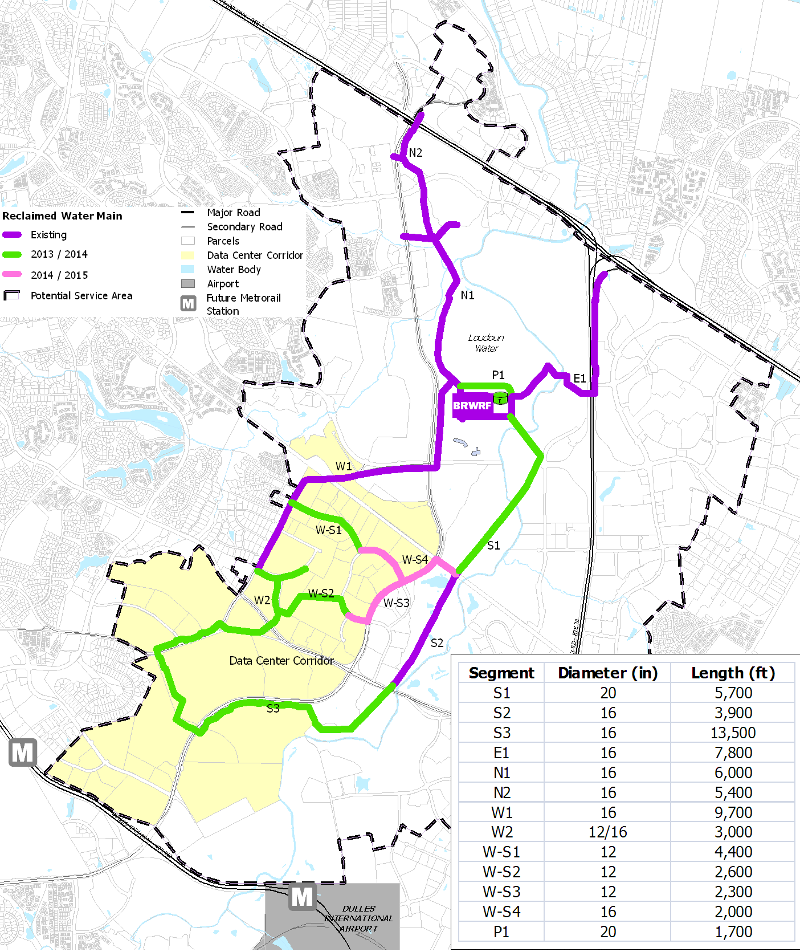

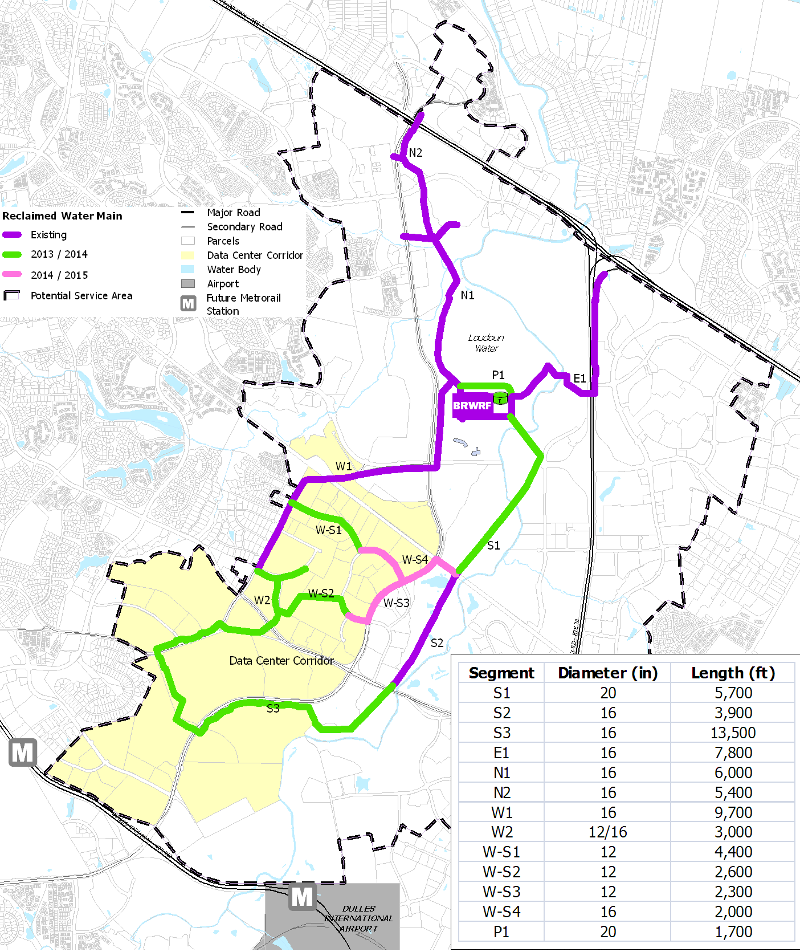

purple pipes will distribute treated wastewater from Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility (BRWRF) in Loudoun County to customers north of Dulles airport

Source: Loudoun Water, Reclaimed Water System Map

The Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility in Loudoun County, which started operations in 2008, was designed to support a network of purple pipes that distribute reclaimed water for irrigation, chilling data centers, and other purposes permitted by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. That facility handles wastewater from a rapidly urbanizing area near Dulles airport.

When Dulles Airport was built in 1961, the Federal government installed a sewer line connecting the airport (and much of then-rural eastern Loudoun County) to the wastewater treatment plant at Blue Plains. By 2000, it was clear that rapidly-growing Loudoun County would need a new sewage treatment plant, because the county was close to exceeding the capacity allocated to it at the Blue Plains facility.

projected demand for sewage processing capability, triggering construction of

Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility as Loudoun County population expands

Source: presentation by Tom Broderick, Broad Run WRF Program Manager,

to Potomac Watershed Roundtable (October 3, 2008)

The Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility uses a different process for stripping waste out of wastewater, immersed membrane technology together with advanced biological nutrient removal, use of granular activated carbon and ultraviolet light disinfection. The end result is clean wastewater intended to be used as a resource, rather than treated as waste dumped into Broad Run.

The Loudoun County Sanitation Authority will distribute treated wastewater in four miles of brightly-colored purple pipes for reuse at the One Loudoun World Trade Center development, the National Rural Utilities Cooperative Finance Corporation building, and to other customers as the area develops - especially data centers needing water for cooling information technology equipment. Use of recycled water helps buildings earn status as "green," according to LEED (Leadership in Environmental and Energy Design) criteria.15

In 2024, the developers of the Culpeper Technology Campus obtained approval from Culpeper County and the Town of Culpeper to use treated wastewater for cooling nine new data centers. The developers will pay the costs for building a 2-million gallon tank to store wastewater, a 4-million gallon per day pump station, and waterlines from the treatment plant to the pump station and data centers. Evaporating the wastewater will reduce the discharge into Mountain Run.16

Also in 2024, Amazon negotiated successfully with Spotsylvania and Caroline counties to develop the Mattameade Tech Campus. The plan was for 11 data centers to be constructed, mostly in Caroline County, and for Spotsylvania County to provide the water utilities. Amazon Data Services had previously planned to use wastewater from Spotsylvania County to cool other planned data centers. For the Mattameade Tech Campus, Amazon committed to invest $15 million to construct a wastewater reuse system.17

Amazon made a similar arrangement with Stafford County. The county agreed to provide potable water for cooling the first data center building on Old Potomac Church Road. Amazon committed to spend nearly $400 million to build the infrastructure required to reclaim wastewater at the Aquia Wastewater Treatment Plant and use it for cooling the second building.

When the Stafford County Board of Supervisors approved the rezoning in 2025 for Amazon to construct its 23-building Stafford Technology Center on 500 acres, the county specified that Amazon would sign a water services agreement to extend the wastewater recycling system to the new data center complex.18

Links

Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility (Loudoun County) (click on images for larger photos)

References

1. "Battling Water Scarcity: Direct Potable Reuse Poised as Future of Water Recycling," WaterWorld, September 1, 2013, http://www.waterworld.com/articles/print/volume-29/issue-9/editorial-features/battling-water-scarcity.html; "Pioneering Water Reuse in the Old West," WaterWorld, May 1, 2009, https://www.waterworld.com/international/desalination/article/16200553/pioneering-water-reuse-in-the-old-west; "Astronauts need clean water. That's an engineering challenge,"

The Washington Post, July 26, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2025/07/26/nasa-water-recovery-astronauts/ (last checked July 27, 2025)

2. "Title 9. Environment - Agency 25. State Water Control Board - Chapter 740. Water Reclamation and Reuse Regulation," 9VAC25-740-10. Definitions, Virginia Legislative Information System, https://law.lis.virginia.gov/admincode/title9/agency25/chapter740/section10/ (last checked May 13, 2019)

3. "Frequently Asked Questions About Water Reclamation and Reuse," Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, https://www.deq.virginia.gov/Portals/0/DEQ/Water/VirginiaPollutionAbatement/Water_Recl_and_Reuse_FAQ%20Sheet%20_5-2014.pdf (last checked May 13, 2019)

4. Guy Carpenter, "Reclaimed Water Trends Nationally and Internationally," Arizona Department of Water Resources, http://www.azwater.gov/azdwr/waterManagement/documents/ReclaimedWaterTrends-GuyCarpenter.pdf; "Making Water Reuse Popular," WaterWorld, January 1, 2013, https://www.waterworld.com/international/desalination/article/16201455/making-water-reuse-popular (last checked May 13, 2019)

5. "Frequently Asked Questions About Water Reclamation and Reuse," Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, https://www.deq.virginia.gov/Portals/0/DEQ/Water/VirginiaPollutionAbatement/Water_Recl_and_Reuse_FAQ%20Sheet%20_5-2014.pdf (last checked May 13, 2019)

6. Clinton E. Parker, John W. Reynolds, "Water reuse at highway rest areas: follow-up of implementation," Virginia Highway & Transportation Research Council, VHTRC 79-R43, April 1979, http://vtrc.virginiadot.org/PubDetails.aspx?PubNo=79-R43 (last checked October 8, 2013)

7. "Water Reuse: Ensuring Wastewater Is Not Wasted Water," HRSD, http://www.hrsd.com/firstreuseproject.shtml; "Water Demand Management," Hampton Roads Regional Water Supply Plan, July 2011, p.5-6, http://www.hrpdcva.gov/departments/water-resources/download-the-plan/ (last checked October 8, 2013)

8. "Design Case Study #2: Brownfield Re-Development - Lambert's Point Golf Club," Environmental Best Management Practices for Virginia's Golf Courses, Virginia Golf Course Superintendents Association, January 2012, pp.169-170, https://cdn.cybergolf.com/images/373/Virginia-BMP-Full-Report-final.pdf; "Lamberts Point Golf Course could close, but a Navy course is now public," The Virginian-Pilot, March 26, 2018, https://pilotonline.com/news/government/local/article_c7534fe8-2eb2-11e8-9e02-77486c0a26a9.html (last checked May 13, 2019)

9. "No other options," Golf Course Industry, September 12, 2012, https://www.golfcourseindustry.com/article/gci0912-using-reclaimed-water-city/; "A Rise in Reclaimed," Superintendent, October 2009, reposted at http://www.vgcsa.org/page.asp?id=373&page=9944&newsId=2389 (last checked May 13, 2019)

10. "Waste Not, Want Not - Reusing Waste Water to Save Energy and Reduce HVAC Costs," Shore Energy Fact Sheets, US Navy, April 2010, https://navysustainability.dodlive.mil/files/2010/04/Dam-Neck-GSHP-Infosheet.pdf (last checked May 13, 2019)

11. "Virginia Beach sewage treatment plant to shut down," The Virginian-Pilot, August 2, 2013, https://pilotonline.com/news/local/environment/article_18c94f0b-592d-5d73-8398-38f623f0d3d9.html (last checked May 13, 2019)

12. "Water Reuse Project," Fairfax County, (last checked October 8, 2013)

13. "Natural Gas - Marsh Run Power Station," Old Dominion Electric Cooperative, http://www.odec.com/View.aspx?page=generation/resources/naturalgas; "Panda Power Funds acquires majority interest in planned Loudoun power plant," Virginia Business, September 24, 2013, http://www.virginiabusiness.com/index.php/news/article/324708 (last checked October 8, 2013)

14. "Leesburg Inks Water Agreement With Power Plant," Leesburg Today, October 26, 2013, http://www.leesburgtoday.com/news/leesburg-inks-water-agreement-with-power-plant/article_e101103a-3ea5-11e3-be33-001a4bcf887a.html (last checked February 12, 2014)

15. "Water Reclamation," Loudoun Water, http://www.loudounwater.org/Residential-Customers/Water-Reclamation/; "Reuse Opportunities," Loudoun Water, http://www.loudounwater.org/Business-Customers-and-Partners/Reuse-Opportunities/ (last checked October 8, 2013)

16. "Water tower for data center cooling approved in CTZ," Culpeper Star-Exponent, December 10, 2024, (last checked December 13, 2024)

17. "Spotsylvania agrees to data center deal with Caroline," Free Lance-Star, December 13, 2024, https://fredericksburg.com/news/local/spotsylvania-agrees-to-data-center-deal-with-caroline/article_149de438-b882-11ef-b9ad-a37f21588a7e.html; "Spotsylvania County, Amazon agree on data center water system work," Free Lance-Star, October 24, 2024, https://fredericksburg.com/news/local/spotsylvania-agrees-to-data-center-deal-with-caroline/article_149de438-b882-11ef-b9ad-a37f21588a7e.html (last checked December 14, 2024)

18. "Stafford Supervisors Approve Stafford Technology Center," FXBG Advance, September 18, 2024, https://www.fxbgadvance.com/p/stafford-supervisors-approve-stafford (last checked Jume 10, 2025)

Sewage Treatment in Virginia

Virginia Places