the dam built in 1957 by the Alexandria Water Company forms the current Occoquan Reservoir

Source: Google Maps

the dam built in 1957 by the Alexandria Water Company forms the current Occoquan Reservoir

Source: Google Maps

The Alexandria Water Company purchased the Occoquan Hydro Electric Company in 1947. Lt. Col. Fred Butterfield Ryons had built a hydroelectric dam on the Occoquan River between 1928-1935, and started the Occoquan Hydro Electric Company. The Alexandria Water Company then build two dams on the Occoquan River in the 1950's to supply drinking water to Fairfax and Prince William counties.

Prior to 1947, the Alexandria Water Company had been providing water to Alexandria from Lake Barcroft. That reservoir had been created in 1915 by building a dam across Holmes Run. In 1942 the Lake Barcroft dam was raised five feet by adding gates at the top. The extra height doubled the size of the lake and increased the storage capacity, enabling the Alexandria Water Company to supply drinking water during the World War II population boom.

Population in Northern Virginia continued to grow at the start of the Cold War, and the Alexandria Water Company projected additional demand would exceed the potential storage capacity of Lake Barcroft. The water company chose to build a new reservoir on the Occoquan River, which had a larger (590 square mile) watershed than Holmes Run and therefore could provide more water. Lake Barcroft was sold to developers who constructed 1,000 houses around it as a viewshed amenity; Lake Barcroft was no longer useed as a water supply reservoir.1

the first Alexandria Water Company dam on the Occoquan River was built in 1950 at the Fall Line, upstream of the Town of Occoquan

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Alexandria Water Company completed a 30-high dam on the Occoquan River in 1950. The dam impounded 55 million gallons and created the first Occoquan Reservoir. In 1957, the company built a 70-feet high dam just upstream of the "low dam." The initial water storage capacity of the high dam is estimated to have been 9.8 billion gallons when the spillway elevation was at 120 feet above sea level. Today the spillway is two feet higher, and the maximum capacity of the reservoir could have been as high as 11.2 billion gallons.

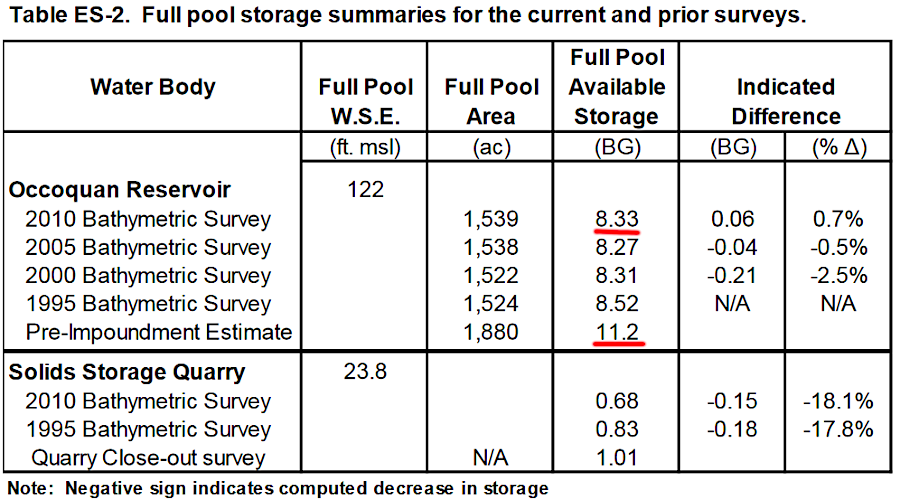

However, since 1957 sediment has accumulated behind the high dam and reduced the volume available for water storage. The reservoir behind the current 72-foot high dam is now calculated to store 8.3 billion gallons of water.

At one time, reservoir depth measurements suggested that sediment was accumulating and the volume reduction was becoming increasingly significant. The utility, now known as Fairfax Water, obtained refined measurements in 2010. It is now thought that the storage volume is stable. Sediment does accumulate during dry years, but large storms (in which the flow can be two feet or more above the spillway) scour out the sediment and wash some downstream.2

the Occoquan Reservoir now stores 8.3 billion gallons of water, less than theoretical 11.2 billion gallon capacity due to sediment taking up some volume

Source: Occoquan Watershed Monitoring Laboratory, Bathymetric Surveys of the Occoquan Reservoir and Fairfax Water Solids Storage Quarry 2010 (p.ES-10)

The reservoir is owned by Fairfax County now. As Fairfax County developed in the 1950's, local officials sought to ensure an adequate water supply for new houses, offices and commercial buildings. The county supervisors created the Fairfax County Water Authority and purchased the Annandale Water Company. Fairfax County then notified the Alexandria Water Company that it would acquire the private company's land and facilities at the Occoquan Reservoir. When the company refused to sell, the county condemned the property and acquired it through eminent domain.

A lawsuit filed in state court determined the price the county had to pay for the assets. The county proposed a value of $28 million, while the company claimed its property was worth $55-65 million.

the Occoquan River in 1937, prior to construction of two dams creating drinking water reservoirs

Source: Prince William County, County Mapper

the 1950 low dam is downstream of the 1957 high dam

Source: Historic Prince William, Occoquan - #77

The jury determining the award visited the water treatment plant and dams, and the Alexandria Water Company ensured all the facilities looked their best before the visit. A common comment when walking through the plant was:3

The final award was nearly $50 million, and the county acquired the property in 1967.4

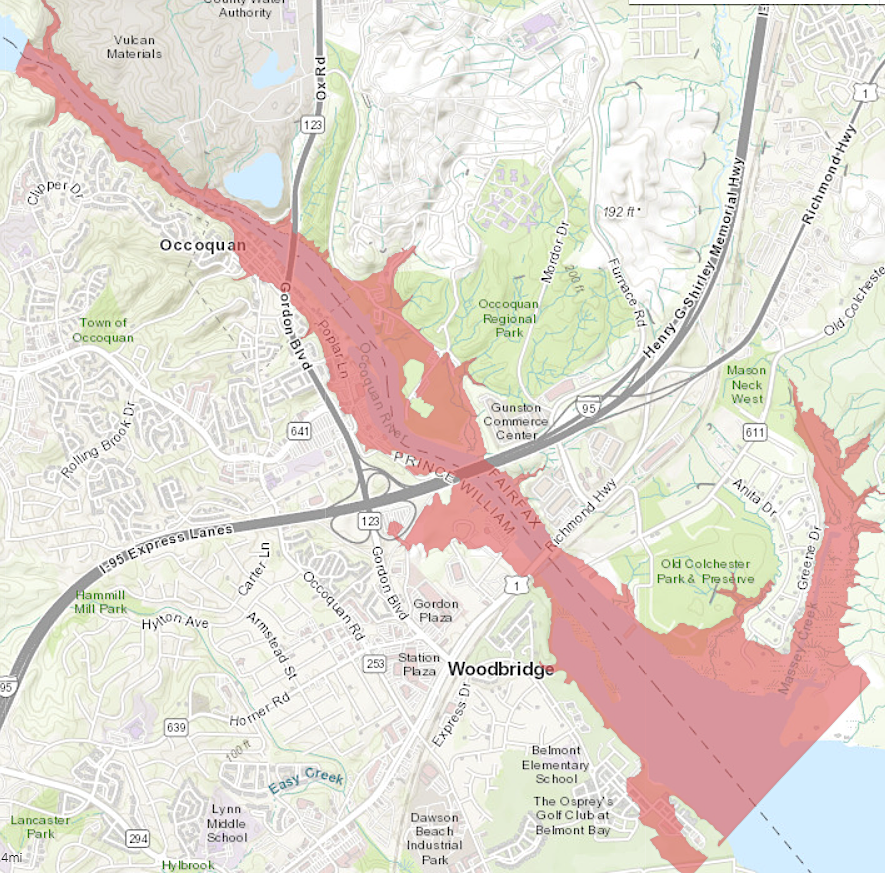

Fairfax Water controls water levels of the Occoquan Reservoir, which backs up into Prince William County

Source: Historic Prince William, Clearing at the end of Lake Occoquan Drive

if one of the dams breaks, a siren alert from Fairfax Water will notify people in the flood zone downstream

Source: Fairfax Water, Occoquan Dam Siren

After Hurricane Isabel in 2003 knocked the water system offline for the first time in its history, Fairfax Water built the Griffith Water Treatment Plant. It replaced three older facilities located along the Occoquan River, and was built on 150 acres acquired by the county when the Lorton prison was closed. Beige-colored bricks were used to mimic the architecture of the old prison. The 120 million gallons per day facility opened in 2006.5

In 2016, the public utility allowed the Town of Occoquan to open up the site of the old treatment plant as River Mill Park.

the old water treatment facilities on the Occoquan River were demolished (except for the underground storage tanks) and the site was opened as River Mill Park on July 30, 2016

The Alexandria Water Company morphed in Prince William County into Virginia-American Water. That private utility continues to supply Alexandria and eastern Prince William County with treated drinking water, which it purchases at wholesale prices from Fairfax Water.

As Fairfax Water expanded its system of pipes to supply drinking water throughout the county, it also had to address eutrophication of the reservoir. Occoquan Reservoir received 3 million gallons/day of treated wastewater discharged from 11 secondary treatment plants in the watershed. High levels of nitrogen and phosphorous in the wastewater allowed excessive growth of cyanobacteria (blue-green algae). Oxygen levels in the water dropped to near-zero and the reservoir literally stank in the late summer months, as massive amounts of cyanobacteria decayed.

It was too expensive to divert the sewage out of the watershed, pumping it to treatment plants that discharged into the Potomac River. In addition, that option just transferred the problem rather than solved it - though Austin, Texas managed to get the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to ban any wastewater discharge into the chain of Highland Lakes on the Colorado River that provide drinking water to that city. Prince William and Fairfax counties lacked the political and economic clout to get the Virginia General Assembly to require that all wastewater generated in the Occoquan River watershed must be pumped uphill for treatment and ultimately release into other streams.

In Northern Virginia, it was unrealistic to limit the population in the watershed to just 100,000 people. Limiting sales and development of private land might have blocked an excessive level of nutrients from being poured into the Occoquan Reservoir, but would have created lawsuits about "inverse condemnation" of land and perhaps required government purchase of many expensive building sites.

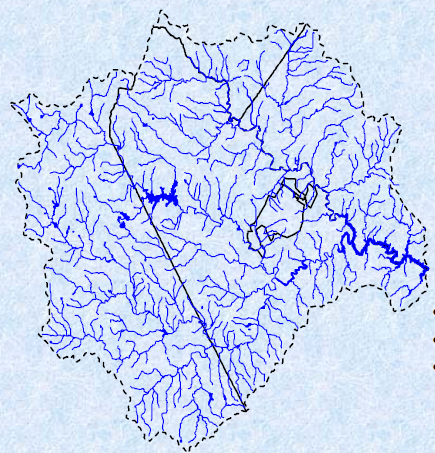

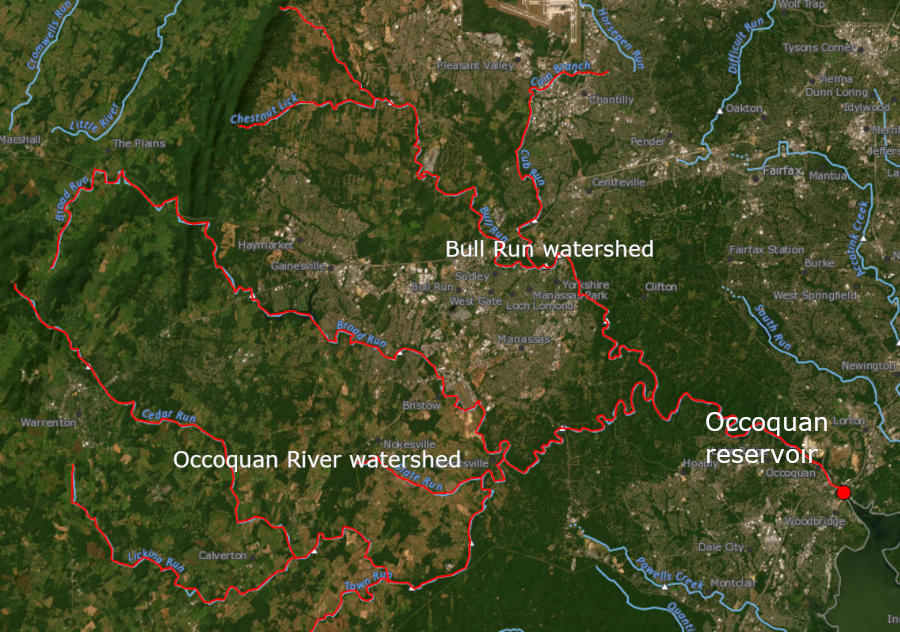

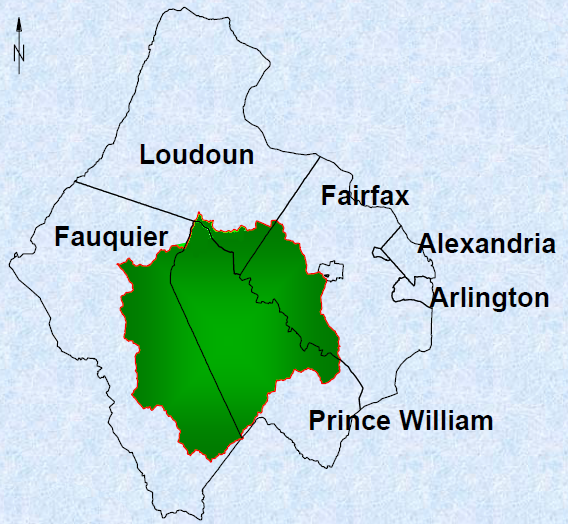

the Occoquan River drains a watershed of 590 square miles

Source: Northern Virginia Regional Commission, Occoquan Watershed: "Where Is It and What s In It"

The solution was to build one or more new sewage treatment plants that could use advanced methods to discharge "clean" water. How to fund the new infrastructure, and how to allocate costs, was a political challenge. The counties of Fairfax, Fauquier, and Prince William, plus the towns (in 1971) of Manassas and Manassas Park, contributed different percentages of waste. The population in each jurisdiction was growing rapidly, so the amount of sewage that they generated - and the ratio that each discharged to the Occoquan - was changing yearly.

The General Assembly acted in response to an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) notification that better treatment was required in order to comply with the Clean Water Act. The state legislature had the authority to impose requirements on the different jurisdictions that generated wastewater flowing into the reservoir, and to charter a multi-jurisdictional agency to manage the sewage. The Upper Occoquan Sewage Authority (UOSA), now known as the Upper Occoquan Service Authority, was created in 1971.

The Upper Occoquan Sewage Authority completed a state-of-the-art wastewater treatment plant in 1978. The facility removed nitrogen/phosphorus, the nutrients which stimulated cyanobacteria growth, and discharged treated water that was clean enough to drink. The 11 old wastewater plants were closed and the reservoir became an attractive artificial lake again. Today, excessive levels of cyanobacteria are kept in check when necessary through application of copper sulphate on the surface of the reservoir.

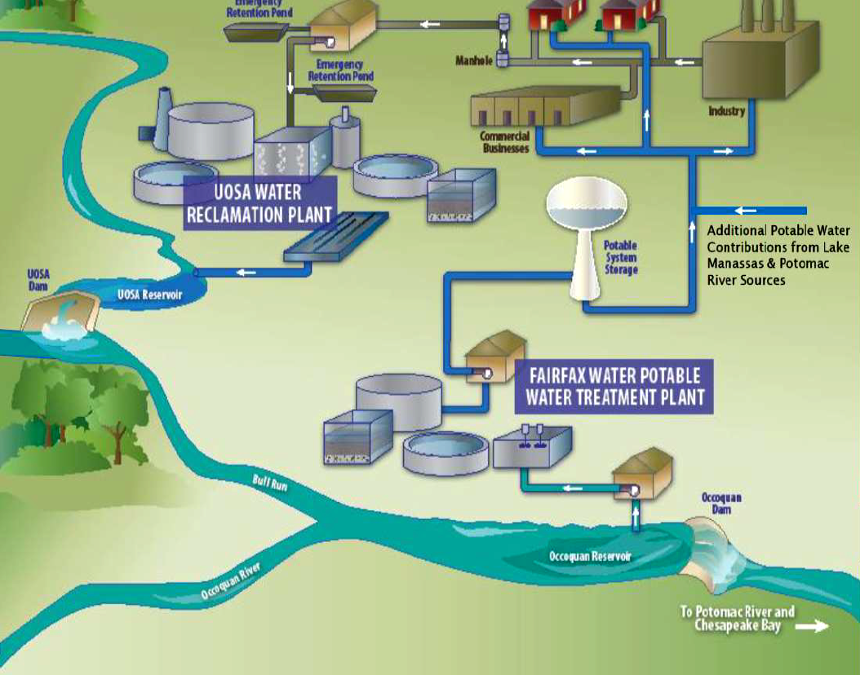

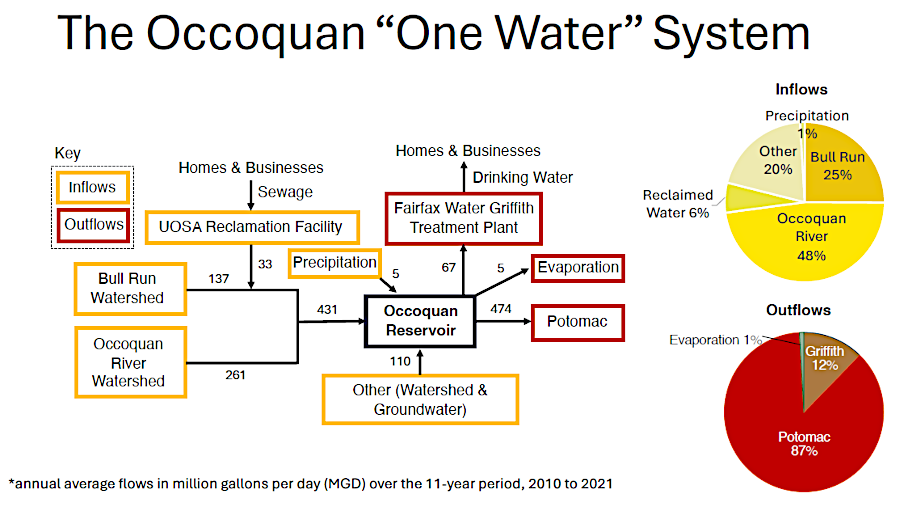

The Upper Occoquan Service Authority treatment plant is located south of Centreville and west of Route 123. That places the discharge pipe upstream of the Occoquan Reservoir. Much of the flow in Bull Run, particularly in the summer, is treated sewage. That wastewater was originally extracted by Fairfax Water from the Potomac River upstream from Riverbend Park, treated to drinking water standards at the James J. Corbalis Jr. Water Treatment Plant near Herndon, and delivered to customers in western Fairfax and Prince William counties plus the City of Manassas Park. City of Manassas has its own drinking water system supplied from Lake Manassas.

Except for rural residences using septic systems, all wastewater in western Fairax and Prince Wiliam counties, plus the cities of Manassas and Manassas Park, flows from toilets, sinks, and showers to the Upper Occoquan Service Authority treatment plant. The sewage is treated there and discharged into Bull Run, a stream which flows down into the Occoquan Reservoir. Water is pumped from the Occoquan Reservoir and processed to meet drinking water standards at the Frederick P. Griffith Jr. Water Treatment Plant, then piped to customers.

Because of the gap between the Upper Occoquan Service Authority discharge into Bull Run and the intake at the Frederick P. Griffith Jr. Water Treatment Plant, the system is not a direct toilet-to-tap process. Bull Run and the Occoquan Reservoir are in the middle, serving as an environmental buffer between wastewater and drinking water facilities.

Regulatory agencies traditionally have decided that putting treated wastewater directly into the drinking water system would be acceptable from a heath standards perspective but politically challenging. An intermediate buffer, even just a short distance in an underground aquifer, increases the general public's willingness to drink recycled wastewater.

In California, Los Angeles built the East Valley Water Reclamation Project in 2000 to recycle wastewater but shut down operations after the general public expressed strong opposition. When Orange County developed its recycling approach in 2015, it conducted a sccessful public education program first. The county now injects treated wastewater into an underground acquifer and then taps that aquifer with drinking water wells nearby.

The San Diego system pumps wastewater treated to meet Safe Drinking Water Act standards into the Miramar Reservoir, then processes the reservoir water through a drinking water treatment plant again before piping it to customers. Following higher recognition of the shortage of water, by 2025 Los Angeles had launched the Pure Water Los Angeles initiative and was planning to upgrade wastewater treatment plants to create drinking water.

As water scarcity has increased, direct reuse systems without an intermediate buffer have been implemented. Texas, California and Arizona now allow it. The town of Big Spring, Texas was the first in the United States to do so in 2013. El Paso began construction of a direct reuse project in 2025. At the time, Tucson, Phoenix, and several smaller communities in the Southwestern United States were planning to recycle treated wastewater directly into drinking water systems.

water is recycled in the Occoquan watershed, going from the wastewater treatment plant to the drinking water treatment plant

Source: Upper Occoquan Service Authority, Using UV-254 as a Surrogate to SCOD and SOC Laboratory Methods to Improve Plant Process Performance

Because such a high percentage of the water in the Occoquan Reservoir comes from Upper Occoquan Service Authority treatment plant, the Virginia General Assembly established an Occoquan Policy setting higher-than-average standards for treatment by the Upper Occoquan Service Authority. The system has been so successful that few customers in eastern Fairfax and Prince William counties pay attention to the fact that they drink treated wastewater, brought to near-drinking water standards at the Upper Occoquan Service Authority and then processed again at Fairfax Water's Griffith Treatment Plant.

That treated wastewater is recycled just once. Almost all eastern Fairfax County consumers served by the Griffith Treatment Plant send their wastewater to be processed at the Noman M. Cole, Jr. Pollution Control Plant near Lorton. Wastewater from eastern Prince William County customers is processed at the H.L. Mooney Advanced Water Reclamation Facility on Neabsco Creek or the Virginia-American wastewater treatment plant further upstream in Dale City.

All three facilities discharge their treated wastewater into tributaries of the Potomac River. Their processed wastewater flows down the Potomac River to the Chesapeake Bay. No communities further downstream draw water from the salty Potomac River.

Many customers in western Fairfax and Prince William counties also drink treated wastewater supplied by Fairfax Water, though the sewage discharge is further upstream from the intake on the Potomac River for the James J. Corbalis Jr. Water Treatment Plant. Multiple cities upstream from that intake, including Staunton on the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, discharge treated sewage (and untreated stormwater) into the Potomac River.

As the river flows downstream, sunlight and oxygen naturally kill harmful bacteria and improve the water quality of the discharged sewage. Because of the distance and dilution within the Potomac River, wastewater treatment plants upstream of the Fairfax Water intake are not required to meet the higher standards established for the Upper Occoquan Service Authority facility.

There are water pollution threats to the Occoquan Reservoir beyond bacteria from human use. Uranium in Fauquier County could contribute unacceptable levels of radioactivity, if that resource was ever mined.6

The 305(b)/303(d) Water Quality Assessment Integrated Report issued by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) listed the upper Occoquan Reservoir (above the second dam) as "impaired." Fish tissue samples have revealed excessively high levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB's), so the reservoir is Not Supporting for fish consumption.7

the Occoquan Reservoir is listed as "impaired" due to excessively high levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB's) in fish tissue samples

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Environmental Data Mapper

Water quality is also at risk from perfluoroalkyl (PFAS) substances and polyfluoroalkyl (PFOA) substances, also known as "forever chemicals" because natural degradation is so slow.

In 2023, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed to lower the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) standards for PFAS from 70 parts per trillion (ppt) set in 2016. If dropped to 4 parts per trillion as initially proposed, a coalition of water treatment agencies claimed:8

"Forever chemical" contamination of the Occoquan Reservoir comes from multiple sources, but two particular sites were potential significant contributors.

In a groundwater test well at the former U.S. Department of Defense base at Vint Hill in Fauquier County, the PFAS level reached 1,200 (parts per trillion). A drinking water well there measured over 36 parts per trillion. The likely source was the burn pit where firefighting foam was used in training exercises.

Another source could be Manassas Regional Airport. In 2020, a sprinkler system released firefighting foam that reached Broad Run.9

PFAS contamination in the Occoquan Reservoir can be traced in part to firefighting foam used at Vint Hill and Manassas Regional Airport

Source: L.C. Nottaasen, Practice with powder and foam extinguishers

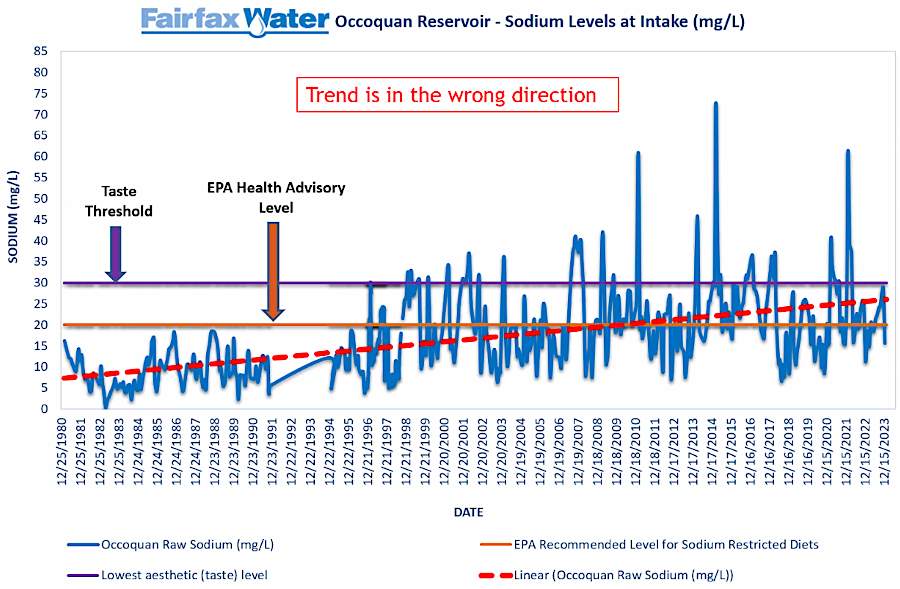

The other significant risk to water quality in the Occoquan Reservoir is increasing salinity. In 2003, the Environmental Protection Agency established an advisory level for individuals with a very restricted total sodium intake. The drinking water threshold for those already at risk of high blood pressure and hardening of the arteries was set at 20 milligrams/liter. For aquatic life, the standard is 230 mg/l. "Freshwater" typically has no more than 500 mg/l, while oceans have 35,000 mg/L (35 parts/thousand) of various salts.10

By 2022, salinity levels in the Occoquan Reservoir were consistently above 20 mg/l and occasionally above 30 mg/l, at which point people can taste it. Blending Occoquan Reservoir and Potomac River water was one possible solution, but at the Fairfax Water intake the Potomac River salinity was reaching 16 mg/l.

The "freshwater salinization syndrome" is a nationwide issue, caused by use of laundry/dishwasher detergents and brine/salt crystals in winter to reduce ice on highways and sidewalks. Humans with a high-sodium diet also flush high-sodium waste from bathrooms.

Source: Prince William Conservation Alliance, https://youtu.be/g3bTK_kwNSA?si=TC5P9smBKGyPxZfe

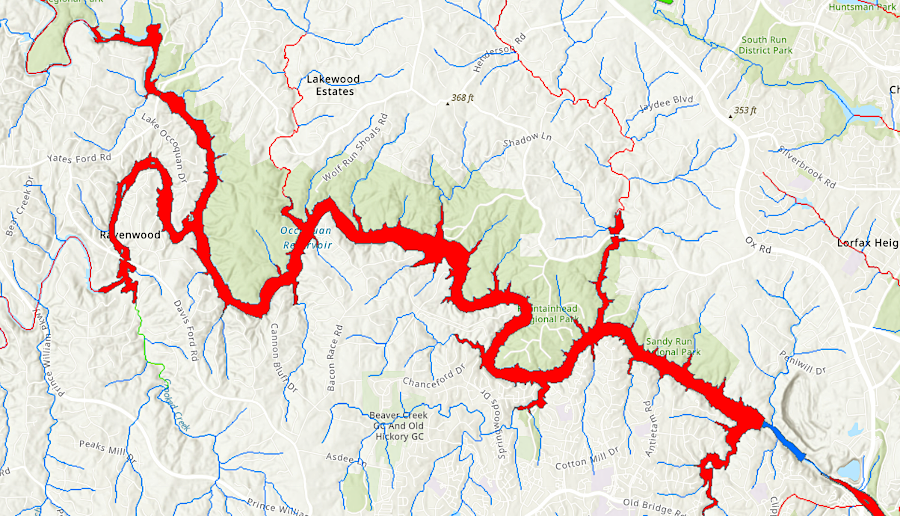

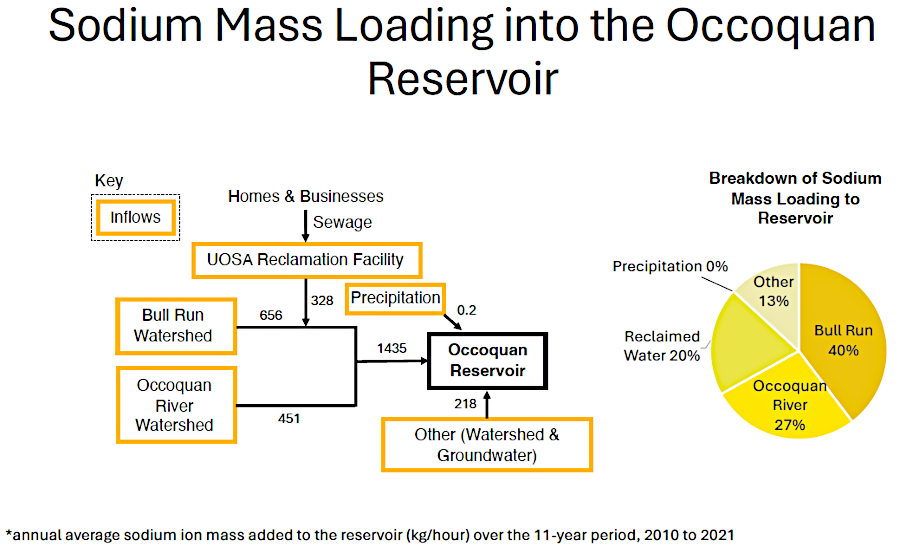

A major source of salt in the Occoquan watershed is runoff from impervious surfaces, especially as snow/ice melts and washes salt applied by homeowners, businesses, and the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) to improve traction. During the wet months, watershed runoff is the greatest source of sodium reaching the reservoir. The more-developed Bull Run watershed delivers more sodium than the Occoquan River watershed. The City of Manassas has a water treatment plant on Broad Run, a tributary of the Occoquan River, and its finished water contains 18.5mg/l of sodium.

the less-developed Occoquan River watershed contributes less-salty water to the Occoquan Reservoir

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

During the dry months, the greatest source of sodium is the wastewater discharged from the Upper Occoquan Service Authority (UOSA) into Bull Run. The treated wastewater has a higher percentage of sodium ions than the water flowing in the two major tributaries, Bull Run and the Occoquan River.

The vast majority of the water and sodium discharged by the Upper Occoquan Service Authority (UOSA) comes from homes and businesses in western Prince William and Fairfax counties. The Micron computer chip manufacturing plant in Manassas uses sodium hydroxide to clean its products, but pre-treatment by the facility reduces the sodium levels below a threshold required by the Upper Occoquan Service Authority.

What humans flush down the toilet is the source of about 15% of the sodium that reaches the wastewater treatment plant. Detergents for washing clothes and dishes vary in their sodium content, but may be a major source as well.

Many homeowners use a water softener, and salt-based water softeners are designed to replace chloride ions with sodium ions. Sodium discharged into septic systems, from homes relying upon well water, eventually will flow via groundwater into Occoquan watershed streams. As the population in the Occoquan Watershed increases, the trend line salinity in the Occoquan Reservoir has been steadily increasing since 1995.

On an annual average, the discharge from the Upper Occoquan Service Authority wastewater treatment plant contains 60-70 mg/l of sodium, which is 4.5 times the concentration of sodium in the waters of Bull Run and Occoquan River. More than any other source, wastewater from 350,000 connections (in 2021) is creating the "freshwater salinization syndrome" in the Occoquan Reservoir:11

salt is increasing in the Occoquan Reservoir

Source: Northern Virginia Regional Commission, Rising Salinity in the Occoquan Reservoir (February 20, 2024)

20% of the sodium in the Occoquan Reservoir comes from wastewater; the other 80% comes from surface runoff

Source: Northern Virginia Regional Commission, Rising Salinity in the Occoquan Reservoir

The Upper Occoquan Service Authority wastewater treatment plant was not designed to extract salt, so the sodium ends up in the Occoquan Reservoir. Fairfax Water's Frederick P. Griffith Jr. Water Treatment Plant at Lorton withdraws raw water from that reservoir, and has no process for desalinization it before delivering treated drinking water to wholesale and retail customers.

The level of salt in that raw water supply ends up as the level of salt in the finished product delivered as drinking water to homes in eastern Fairfax County and Prince William County. Standard water filters placed on faucets within homes do not remove salt; a reverse osmosis system is required for that process. Fairfax Water would have to spend about $1 billion to implement reverse osmosis to treat the water at the Griffith facility.12

The lowest cost tool for protecting water quality, the preservation of forested stream valleys in designated Resource Protection Areas (RPA's) extending 100 feet on eiher side of perennial streams, will not diminish salt runoff into the reservoir significantly. Plants do not assimilate much salt, so stormwater runoff will continue to carry dissolved sodium and chloride through the forested buffer into tributaries of the reservoir.13

Source: Prince William Conservation Alliance, Protecting the Occoquan Reservoir: Our Shared Water Source (2022)

Source: Prince William Conservation Alliance, Protecting Our Drinking Water: A Community Approach to the Occoquan Reservoir

the Occoquan Reservoir receives wastewater from the Upper Occoquan Service Authority

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

wastewater treatment tanks at Upper Occoquan Sewage Authority

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

Fairfax Water maintains a warning system, in case the dams on the Occoquan River are at risk of breaking

Source: Fairfax Water, Occoquan Dam Siren

Source: Northern Virginia Regional Commission, Reclaiming Our Water - The Occoquan River Watershed

the Occoquan Reservoir receives stormwater runoff from Loudoun, Fairfax, Fauquier, and Prince William counties

Source: Northern Virginia Regional Commission, Occoquan Watershed: "Where Is It and What's In It"

on average, Fairfax Water withdraws 12% of the water that flows out of Occoquan Reservoir

Source: Prince William Water, Briefing to Prince William Board of County Supevisors (December 10, 2024)

Occoquan reservoir in 2010, showing how land use planning in 1980-2000 led to contrasting levels of development on Fairfax County vs. Prince William County sides

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Occoquan 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2010)