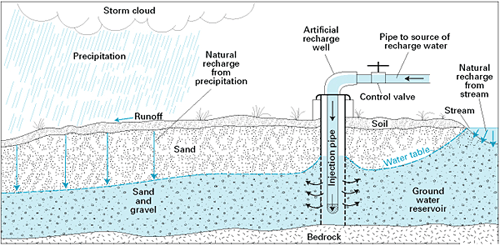

the Sustainable Water Initiative for Tomorrow (SWIFT) Project pumps treated wastewater into aquifers underneath Hampton Roads

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Groundwater can be recharged naturally and artificially

the Sustainable Water Initiative for Tomorrow (SWIFT) Project pumps treated wastewater into aquifers underneath Hampton Roads

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Groundwater can be recharged naturally and artificially

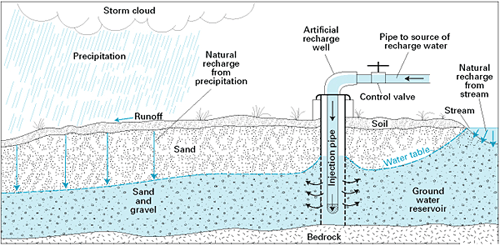

Withdrawal of groundwater from the Potomac Aquifer increased starting in the 1940's and peaked in 1990. Paper plants in Franklin and West Point were particularly heavy users, and land subsidence near them was the greatest in the Coastal Plain. Groundwater levels declined until 2007, and have been increasing since then. Withdrawal permits issued under the state's 1973 Groundwater Management Act were revised in 2017, reducing authorized withdrawals to essentially the level being used at that time.1

starting in the 20th Century, groundwater withdrawals from the Potomac Aquifer exceeded the natural recharge rate

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Virginia Coastal Plain Aquifer System (presentation by Scott Kudlas, June 27, 2022)

The Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD) has committed to spend $1 billion for an innovative solution to two problems. In 2017, wastewater from all but one of the district's 13 treatment plants was discharged into the Chesapeake Bay or a tributary. That wastewater carried too much phosphorous and nitrogen into the bay, adding to the excessive levels of nutrients that resulted in low levels of dissolved oxygen.

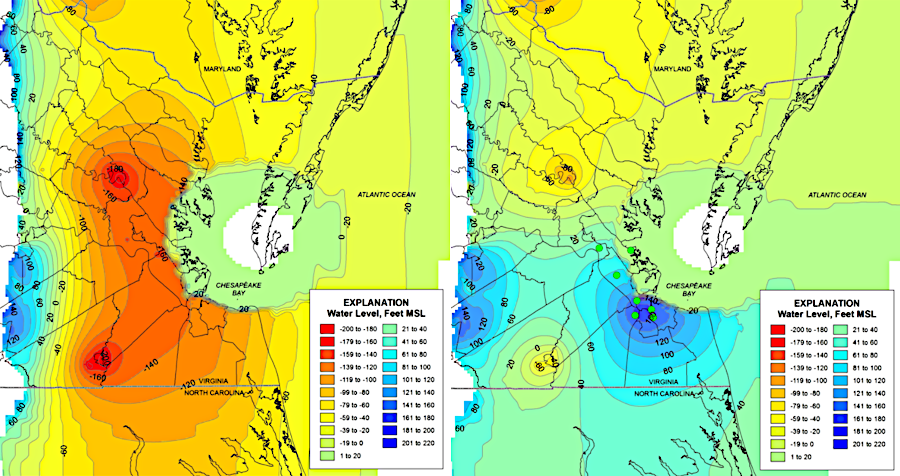

In addition, extraction of groundwater in the region had led to ground subsidence significant enough to increase the predicted destructive impacts from future sea level rise, and to increase the threat of saltwater intrusion into the bottom of existing wells. Sea level was rising 4 millimeters a year, the second-highest level of sea level rise in the United States after New Orleans. Continued subsidence would result in greater damage to local infrastructure in times of high water, such as king tides.

The innovative solution was the Sustainable Water Initiative for Tomorrow (SWIFT). The Hampton Roads Sanitation District planned to treat wastewater to drinking water standards, then inject it deep into the Potomac Aquifer. Injecting the treated wastewater underground into the Potomac Aquifer rather than discharging it on the surface would eliminate the delivery of nutrients into the bay and retard or even reverse land subsidence.

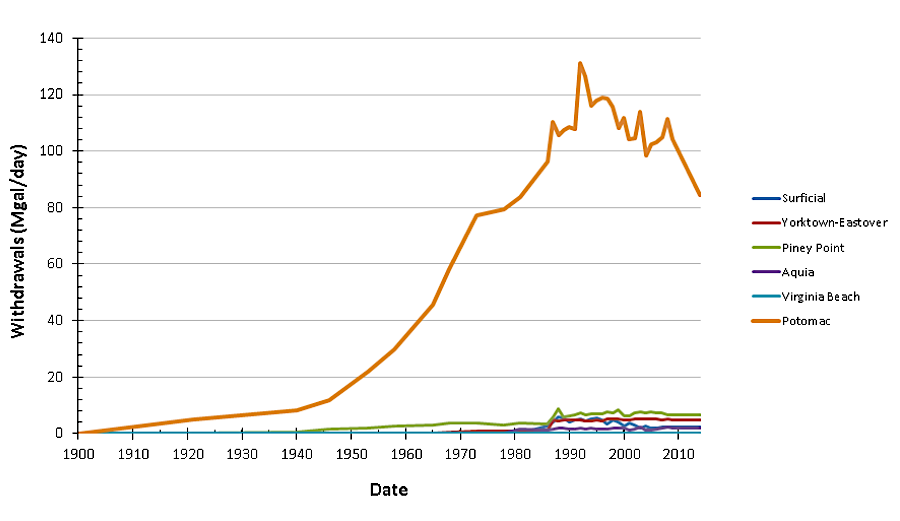

SWIFT was designed to recharge the Potomac Aquifer, the primary source of groundwater extraction on Virginia's Coastal Plain

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Virginia Coastal Plain Aquifer System (presentation by Scott Kudlas, June 27, 2022)

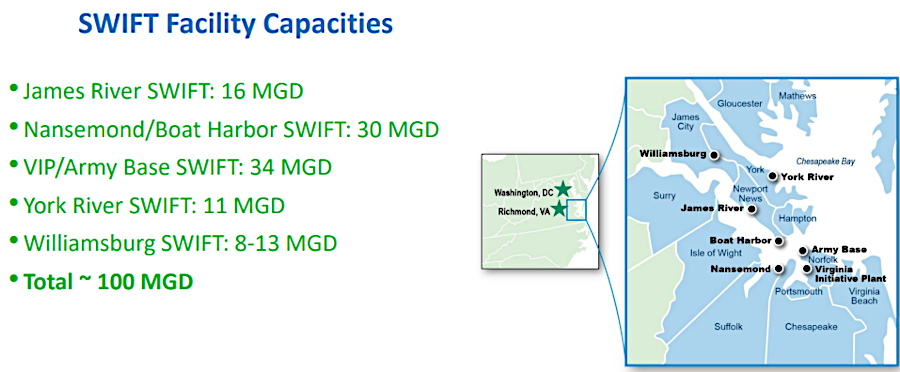

The natural recharge rate into the Potomac Aquifer was far below the amount being withdrawn, with an average of 155 million gallons being withdrawn each day. Sustainable Water Initiative for Tomorrow (SWIFT) was designed to inject over 100 million gallons a day, of the 150 million gallons per day processed by the Hampton Roads Sanitation District. Injection would increase pressure in the aquifer to offset the effects of groundwater withdrawal, as well as eliminate delivery of nitrogen to the Chesapeake Bay.

recharging the Potomac Aquifer was planned by injection of treated wastewater at five sites

Source: Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD), SWIFT capacity context (June 23, 2022)

The $1 billion price tag was staggering, but alternative ways to reduce nutrient pollution and Save the Bay could have been even more expensive. Wastewater treatment plant upgrades could match the success of Northern Virginia plants, upgrading to maximum feasible treatment technology in order to reduce nitrogen levels to 3mg/l.

However, the space available at different wastewater treatment plants for additional tanks required for additional nitrogen removal capacity was limited. Another likely alternative was to reduce stormwater runoff into local creeks, but the land and cost required to build stormwater ponds would be high and the water quality improvement would not be sufficient to meet the limits established in the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) developed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

In the Sustainable Water Initiative for Tomorrow (SWIFT) project, wastewater would be treated to drinking water standards but it would not be re-used for that purpose in a "toilet to tap" program. The proposal by Newport News to build the King William Reservoir revealed that there was an adequate supply of drinking water in the region; additional groundwater withdawals were not required to meet projected demand.

The Hampton Roads Sanitation District had no market for selling wastewater that met drinking water standards. However, injecting it would create an underground reservoir in the aquifer that localities might tap in the future:2

The concept of injecting wastewater was tested at the Nansemond plant, starting in 2016. The James River Treatment Plant in Newport News was chosen to be the first facility with full-scale injection capacity.

Testing indicated that organic compounds such as 1,4-dioxane, nitrosamines, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) were not detected in the injected groundwater. However, the initial well drilled to test the injection process experienced clogging and loss of recharge capacity.

In 2022, construction started on a four-year project that would allow injection of nearly 16 million gallons a day by 2026. The full-scale production well at the James River Treatment Plant was larger, packed with silica beads and gravel. Groundwater models predicted that at the James River Treatment Plant:3

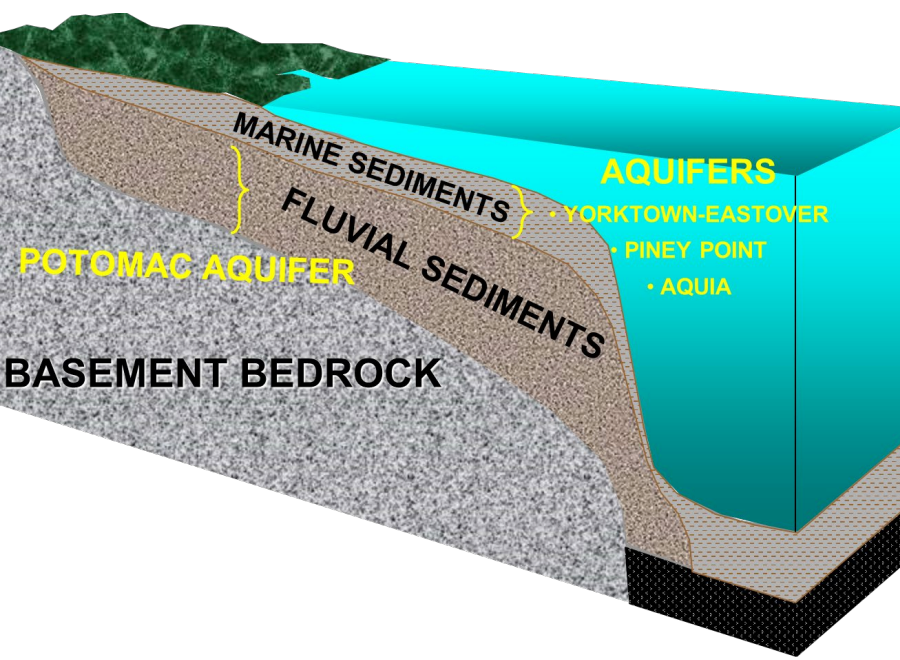

predicted pressures in the Potomac Aquifer in 50 years without SWIFT replenishment (left) and with replenishment (right)

Source: Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD), The Potomac Aquifer: A Diminishing Resource