Virginia and Pennsylvania shared a border between 1681-1863

Source: National Atlas

Virginia and Pennsylvania shared a border between 1681-1863

Source: National Atlas

Today there is no common border between Virginia and Pennsylvania - but between 1681 and 1863, the southwestern border of Pennsylvania was shared with Virginia. Exactly what territory was Virginia and what was Pennsylvania was a challenge that took a century to resolve.

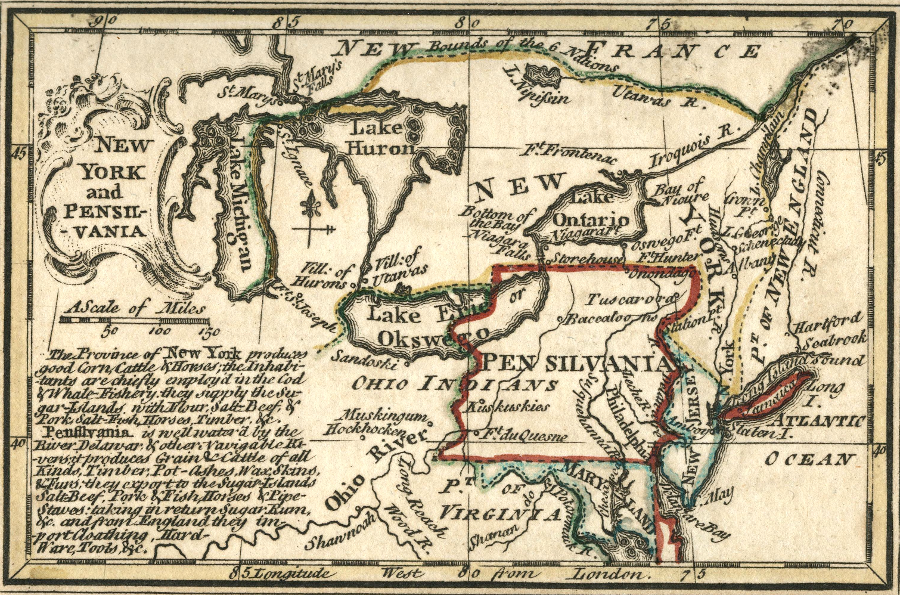

The western boundary of Pennsylvania was established in William Penn's 1681 charter. It was dependent upon the longitude of the eastern boundary:1

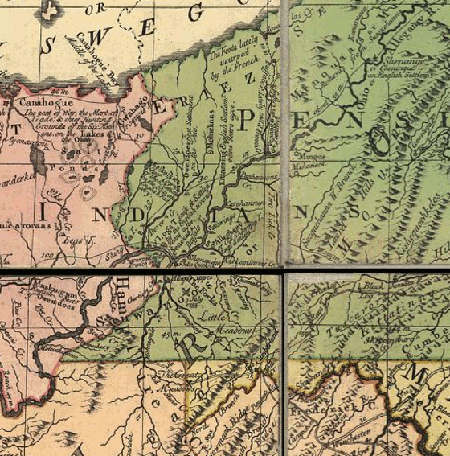

according to William Penn's charter, the western edge of Pennsylvania was supposed to mirror the curving boundaries on the east so the width of the colony would be a constant five degrees in longitude

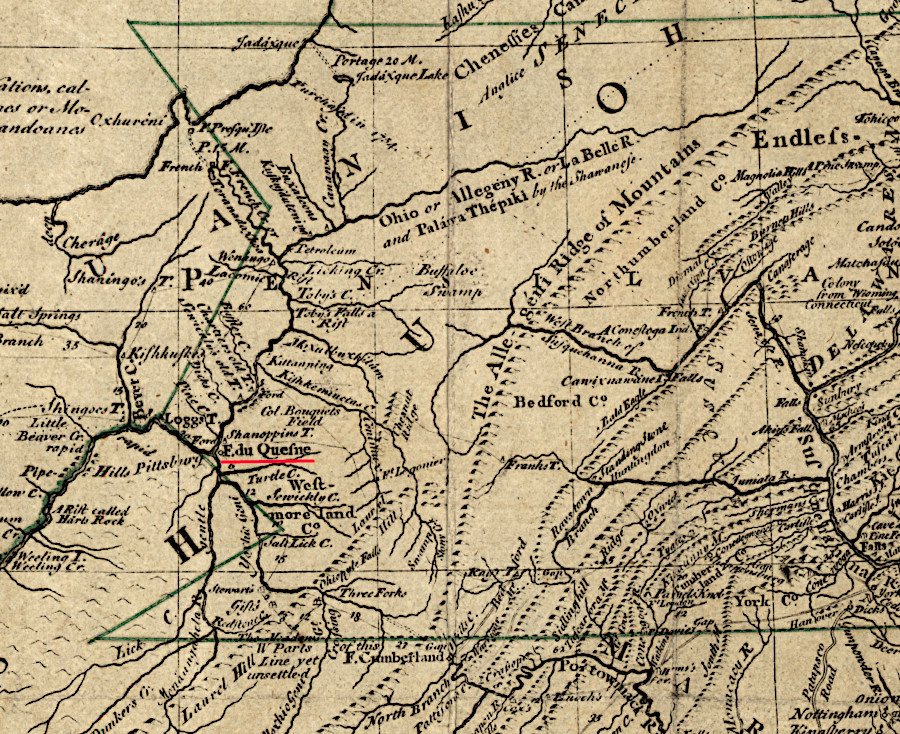

Source: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, New York And Pennsylvania (by Emanuel Bowen, 1758)

William Penn was determined to acquire the Native American claims to his land by legitimate negotiations and purchases, but his efforts to negotiate with fellow Europeans claiming land in North America were even more difficult.

The fundamental problem with Penn's charter was that the point of beginning for his southeastern boundary did not exist. Penn's charter started with the intersection of a circle 12 miles from New Castle (now located in Delaware) and the beginning of the 40th degree of latitude:2

Why King Charles II may have thought the 40th parallel was an appropriate southern boundary for Pennsylvania: John Smith's map located it just at the northern tip of the Chesapeake Bay

(NOTE: Smith's map was oriented with north to the right, and top of the map was the western edge)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606

However, the 40th degree is so far north of New Castle that the lines never intersect. The geographic impossibility in the 1681 charter created great confusion between the Calverts of Maryland, the Penns of Pennsylvania, and even the gentry of Virginia.

Some Pennsylvania officials tried to expand their claim by asserting that the "beginning" of the 40th degree of latitude was the 39th parallel; therefore all land north of the 39th degree of latitude was included in Penn's grant. That extra degree of latitude would have moved the Maryland-Pennsylvania boundary to the south by roughly 69 miles.3

the 40th degree line of latitude runs through Philadelphia, and does not intersect a circle with a 12 mile diameter centered on New Castle

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the British and French dominions in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements

The southwestern corner of Pennsylvania was defined by Penn's charter; it was five degrees of longitude to the west of the southeastern corner. Until the eastern and southern boundaries of Penn's colony were defined, however, it was impossible to establish the western edge - and without accurate clocks, measuring longitude accurately on the frontier was a challenge.

40th degree of latitude and spring at head of Potomac River, landmarks which defined the future Maryland-Pennsylvania-Virginia borders

Source: Library of Congress, A map of Pensilvania, New-Jersey, New-York, and the three Delaware counties (by Lewis Evans, 1776)

The confusion among the colonists and officials in London was minor compared to the threat from the French. That nation had explored the Mississippi River and claimed its watershed, including the lands where water flows into the Ohio River, since René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, canoed downstream and reached the mouth of the Mississippi River on April 9, 1682.

La Salle established the French claim to the Ohio River watershed in 1682 when he reached the mouth of the Mississippi River

Source: National Gallery of Art, La Salle Claiming Louisiana for France. April 9, 1682 (by George Catlin, 1847-48)

The French did not accept the western land claims of Penn or Calvert. To the King of France, there was no validity to the Virginian claim that King James I's Second Charter in 1609 granted them land "from sea to sea" and thus control over most of the Ohio River watershed.

England and France were rivals for control of land and the North America fur trade since the start of the 17th Century. French-English competition extended inland from the fishing fleets on the Grand Banks off Newfoundland to the Ohio River Valley.

The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle settled the War of Austrian Succession, one of the many French/English conflicts in Europe. North America was a minor sideshow in what was known as King George's War. The treaty negotiators who ended the conflict were more concerned with Europe, and failed to resolve the claims of Virginia to lands that the French also claimed in North America.

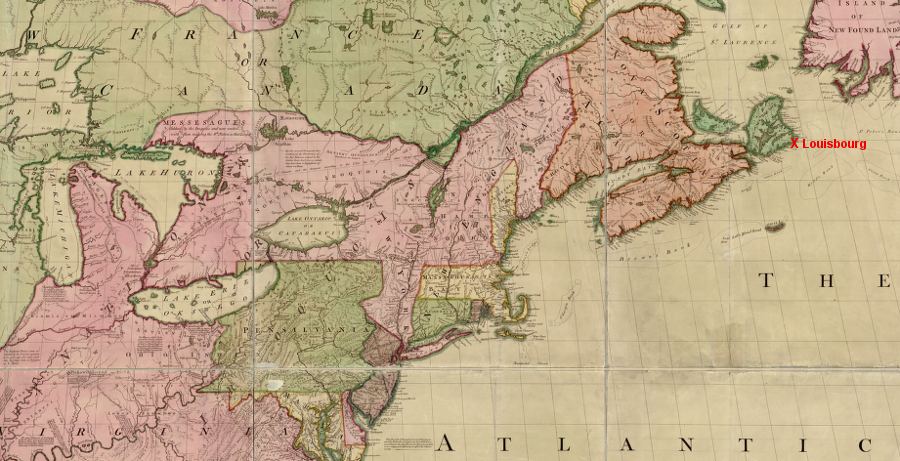

During King George's War, the colonists had captured Louisbourg (a French fortress on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia) with assistance from the British Royal Navy. This was a big deal in North America; it gave the English control over the valuable fishing grounds near Newfoundland.

Louisbourg was far from Virginia, but its return to France in the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle indicated how British officials focused on reducing the French threat in Europe and viewed North America as a secondary theater

Source: Library of Congress, John Mitchell, A map of the British and French dominions in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements (1755)

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle negotiators in Europe undid the capture. The treaty restored that fortress to France in exchange for territory captured by the French in India and Europe. The return of Louisbourg and the failure to resolve French claims to the Ohio River Valley, made clear that English officials based in London considered the western extent of the American colonies to be just a subordinate boundary issue in international negotiations.

The French planned to expand their control of lands west of the Alleghenies. When English explorers were just beginning to penetrate lands west of the Shenandoah Valley in the 1740's, the French took action to link their outposts along the St. Lawrence River to other French settlements at the mouth of the Mississippi River and upriver in the Illinois country.

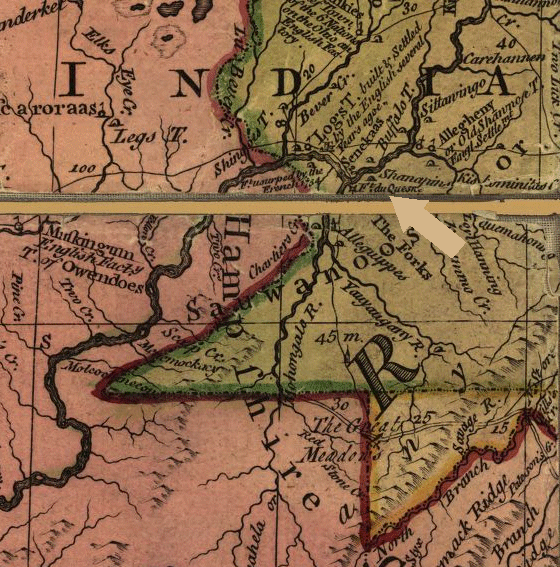

In 1749, Captain Bienville de Celeron canoed from Montreal down the Ohio River and then back up the Miami River to Lake Erie. The French buried lead plates on the Ohio River at various confluences with major creeks, while shouting "Vive le Roi" to establish the claim of the King of France to the Ohio River watershed. Perhaps more importantly, de Celeron chased British traders away from Native American villages.4

Ohio River watershed (in orange)

Source: National Atlas

The French planned to build a series of forts along the Ohio River, extending supply lines from Quebec/Montreal on the St. Lawrence River. This would trap the English colonies along the Atlantic Ocean, blocking any expansion west into the Ohio River/Mississippi River watersheds.

French plans were triggered in part by plans of Virginians to expand into the same region. In particular, in 1749 the Lords of Trade in London approved a grant to the Ohio Company for up to 500,000 acres west of the Allegheny Mountains.

The company was formed by members of the Virginia gentry, who wisely included Governor Dinwiddie and the influential merchant in London John Hanbury. Under the terms of the initial grant, in exchange for settling 100 families and building a fort within seven years, the company would earn its first 200,000 acres.

Thomas Lee, a member of the Ohio Company, was Acting Governor in Virginia in late 1749 after Governor William Gooch returned to England. Lee wrote the governor of Pennsylvania to alert him about the Ohio Company's plans to "to erect and Garrison a Fort to protect our trade (from the French) and that of the neighboring Colonies." Building a fort and maintaining a garrison sufficient to protect the settlements was a requirement of the grant made to the Ohio Company.

A month later, acting Governor Lee added in another letter that the boundary between Pennsylvania and Virginia needed to be defined:5

The Ohio Company sent Christopher Gist to explore around the Forks of the Ohio in 1750 and established a field headquarters/fort at Wills Creek (now Cumberland, Maryland). In 1752, the Ohio Company got the original 1749 land grant terms altered by the Lords of Trade. The company committed to settling 300 families and building two forts, in exchange for removal of any deadline and for granting the entire 500,000 acres.

Location of the land grant was specified in 1752 as:6

the Ohio Company, a syndicate of land speculators including key officials in Virginia, obtained rights to survey and sell 500,000 acres in the Ohio River watershed between the Allegheny River and the Kanawha River (including its tributary, the New River)

Source: The Ohio Company, a colonial corporation (facing title page)

The members of the Ohio Company land syndicate were the colonists most concerned about Captain Bienville de Celeron and the French claims. Ohio Company shareholders included Thomas Lee, president of the Governor's Council (and acting govenor in the absence of Governor Gooch), and Governor Dinwiddie himself. Lawrence Washington was a member until he died from disease in 1752.

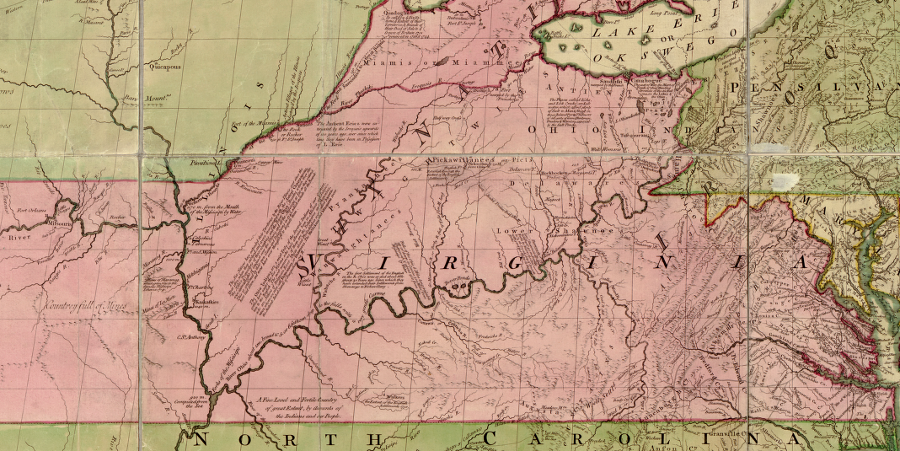

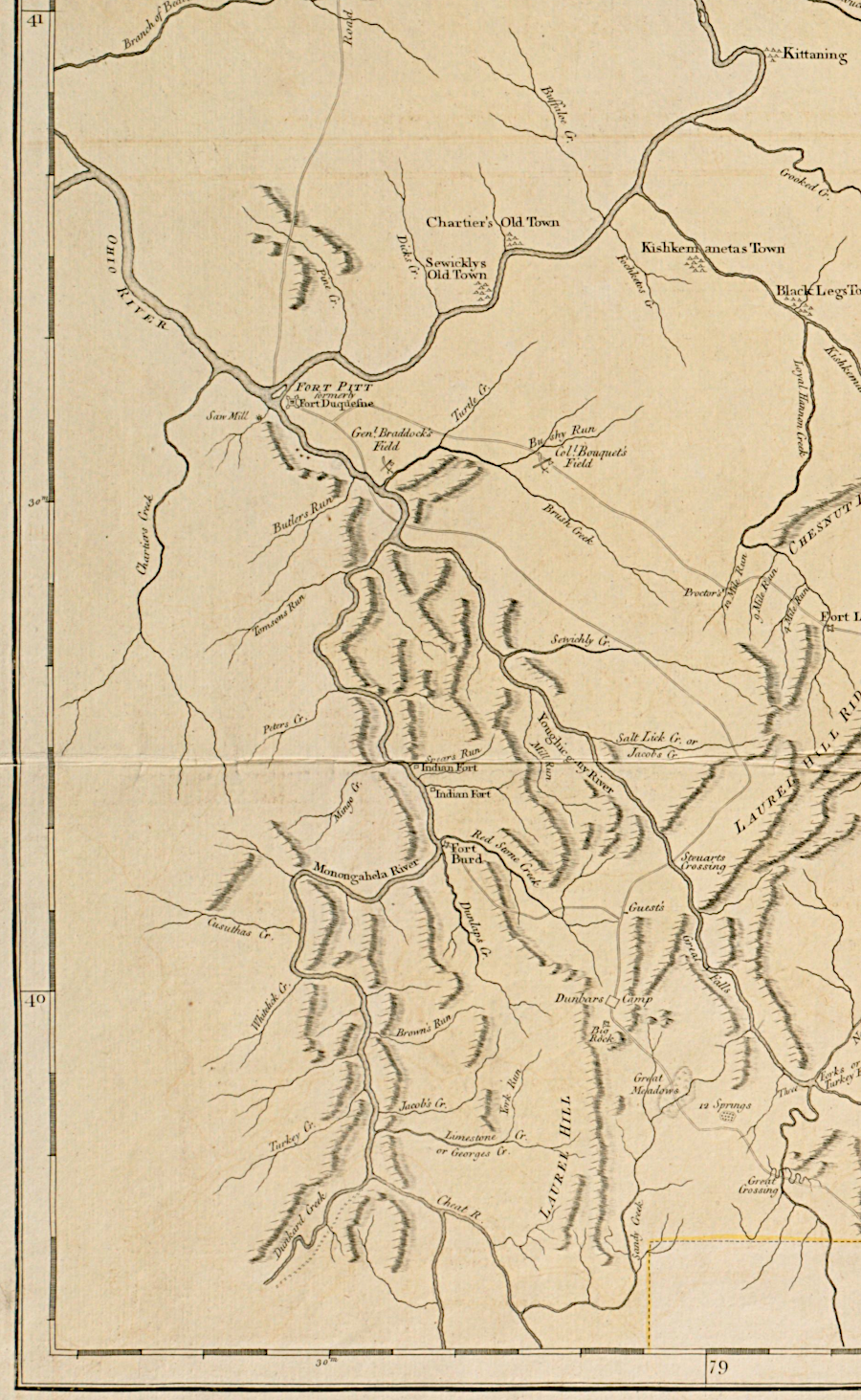

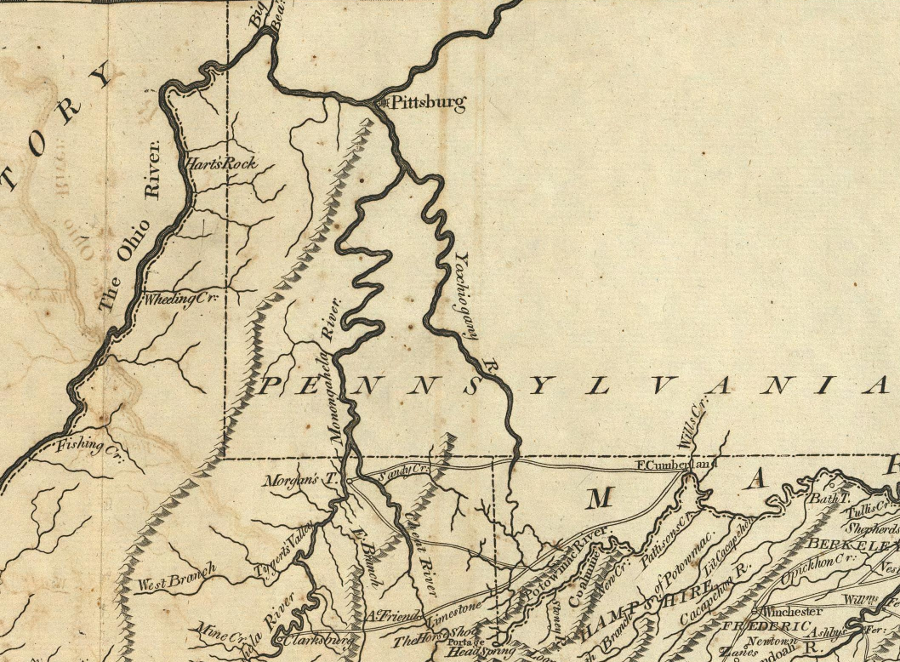

Viewed from Williamsburg, the Ohio River was in Virginia rather than in Pennsylvania. Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson updated their map of Virginia throughout the 1750's to include information acquired from Gist's journeys and later during the French and Indian War, but always indicated that the Virginia boundary was east of the Forks of the Ohio. That placed the Ohio Company's Fort Prince George (later Fort Duquesne, Fort Pitt, Fort Dunmore, and finally Pittsburgh) in Virginia.

Governor Dinwiddie wrote to Pennsylvania Governor James Hamilton on March 21, 1754:7

Governor Dinwiddie requested authorization from London to take action against the French. He received clear direction:8

the Ohio Company started to build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio, but the French seized it and completed Fort Duquesne

Source: University of Pittsburgh - Darlington Digital Library, Part of the Ohio River... and the courses of Christopher Gist's first and second tours

In England, John Mitchell produced a map in 1755 to display the English claims on the North American continent. It identified all the lands west of Pennsylvania as "Virginia." The Mitchell map also colored the lands west of the Mississippi River to show Virginia owned the lands between the 36° 30' parallel of latitude and the 40° parallel.

Virginia's control to the Pacific Ocean was defined in the Second Charter in 1609, issued by King James I. The boundary on the north was limited by the 1620 New England charter and later grants to others. Mitchell's map acknowledged Virginia's claims to lands west of Pennsylvania and east of the Illinois river, accepting the Ohio Company's grant, but did not indicate Virginia owned lands above the 40° parallel west of the Illinois River. On the south, Virginia's boundary was defined at the 36° 30' parallel by the 1665 grant of North Carolina to the eight proprietors.

on the 1755 Mitchell map, lands west of the Ohio River and north to Canada were identified as part of Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, John Mitchell, A map of the British and French dominions in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements

However, Mitchell disagreed with the maps produced by Virginians and placed the Forks of the Ohio within the boundaries of Pennsylvania. A map produced by the father of Patrick Henry in 1770 repeated the Virginia claim that Fort Duquesne/Pittsburgh was west of the Virginia-Pennsylvania boundary.

the 1755 Mitchell map did not accept Virginia's claim to the Forks of the Ohio - and did not define western Pennsylvania's boundary by a line of longitude 5 degrees west of the eastern boundary of that colony

Source: Library of Congress, John Mitchell, A map of the British and French dominions

in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements

a 1771 version of the Lewis Evans map made clear that Pennsylvania included the Forks of the Ohio

Source: Library of Congress, Lewis Evans, A general map of the middle British colonies in America (1771)

The Virginia claim to the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers (the "Forks of the Ohio River") was also based on the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster with the Iroquois. During the treaty negotiations, the Iroquois claimed their controlled lands west of the Allegheny Mountains by right of conquest:9

The Virginians claimed to have purchased those Iroquois rights in the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster. In the 1750's, colonial officials in Williamsburg were willing to assert Virginia's ownership through multiple claims, including right of conquest, initial settlement, and royal grants.

Pennsylvania officials highlighted that any claim to western lands based on Virginia's 1609 charter were invalidated when King James I revoked the charter of the Virginia Company in 1624. The king could alter the boundaries of a royal colony at any time, while the proprietary grant to William Penn was a contract that the king could not change unilaterally. From the perspective of colonial leaders in Philadelphia, the Penn family had the most legitimate claim to the Forks of the Ohio.

The French, of course, did not feel obliged to honor any English claims. French military expansion into the Ohio River Valley would block the claims of any English colony to the land. French occupation, starting with forts and traders and ultimately settlers, would ensure continued French control over trade with the Native Americans west of the Alleghenies.

from the French perspective in the 1750's, the Allegheny Front defined the boundary and all of the Ohio River Valley was part of Louisiana

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing French occupation of the Ohio Valley (1755)

The pacifist Quakers in the Pennsylvania legislature were unwilling to raise taxes to confront and potentially fight the French. In contrast, the Virginians were willing to assert their land claims and be aggressive in their behavior towards the French.

In late 1753, Governor Dinwiddie sent an emissary in the middle of the winter to tell the French to abandon their plans to build a string of new forts from Lake Erie down into the Ohio River valley. The governor chose Lawrence's half-brother George to travel to the French fort near Lake Erie during the middle of winter and direct the French to leave the Ohio River.

An ambitious, risk-taking 21-year old George Washington carried a specific message from Governor Dinwiddie to the French while they were camped at Fort Le Boeuf south of Lake Erie:10

George Washington's map showing Fort Le Boeuf, near Lake Erie

Source: Library of Congress, George Washington's map, accompanying his "journal to the Ohio", 1754

George Washington's path across the Potomac-Ohio watershed divide to Fort Le Boeuf

Source: Library of Congress, George Washington's map, accompanying his "journal to the Ohio", 1754

Washington relied upon Christopher Gist and a few Native American guides, including Tanacharison ("Half King"), to cross the wilderness and reach Fort Le Boeuf in mid-December, 1753. He was well treated by the French officers commanded by Captain Philippe-Thomas Chabert de Joncaire. Camped in the middle of nowhere during the cold winter, they must have been entertained by the company of a young, smart, and well-spoken representative from Williamsburg.

Washington had no military force with him, and no leverage. The French sought to recruit his Native American allies and may have succeeded in getting one to try to murder Washington during the trip home.

Virginia protests failed to convince the French that they should alter their strategic initiative to occupy the Ohio River Valley. The French politely rejected all of the English claims to the Ohio River and sent Washington back to Williamsburg empty-handed.

Fort Le Boeuf was built 15 miles from Lake Erie, across the watershed boundary on a tributary of Allegheny River near modern-day Waterford, Pennsylvania

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Ohio Company sent a party led by William Trent to the Forks of the Ohio in early 1754 to construct Fort Prince George. Governor Dinviddie commissioned Trent as a captain in the Virginia militia, but provided no funds to pay his men or to build a fort. Trent committed Ohio Company funds to pay the men as volunteers, and also enrolled them in the militia. As volunteers, they had been promised two shillings/day in pay. As militia, the colonial government planned to pay them only eight pence per day.

Trent was not the first European to establish a claim at the headwaters of the Ohio River. In 1749 the Governor-General of Canada had sent an expedition led by Captain Bienville de Celeron down the river to disrupt the sale of furs to English traders. On July 29, 1749 the French buried an inscribed lead plate "at the confluence of the Ohio and Kanaragon" (Monongahela and Allegheny) rivers to reinforce their claim to the entire Mississippi River watershed.

George Washington's visit to Fort le Boeuf in 1753 put the French on notice that the Virginians were crossing the mountains. Native American allies informed the French about the construction of the Ohio Company's new fort in 1754. In response, Captain Claude Sieur de Contrecoeur led a military force from Venango to the Forks of the Ohio. When the 1,000 French soldiers arrived on April 17, 1754, in 60 batteaux and 300 canoes with 18 cannon, the 41 Ohio Company workers quickly surrendered. The French built their own Fort Duquesne on that site.

Trent had sent a warning earlier to Alexandria. That message arrived on April 19, as George Washington was gathering soldiers for the Virginia Provincial Regiment. A day later came a report of the fort's surrender. Governor Dinwiddie decided to respond with military force.

Joshua Fry was tasked to organize and lead a Virginia Regiment of Provincial Regulars on an expedition to the Ohio River, to establish an English presence at that strategic location. However, Fry died on May 31, 1774 after falling off his horse. George Washington, though young and without any formal military training or experience, assumed command of the regiment. He led the colonial military expedition into major failure, both military and diplomatic.

Washington attacked a French unit encamped in a Pennsylvania valley (now called Jumonville Glen) east of Fort Duquesne. The Virginians killed nearly all of the French, including their leader Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville. Washington retreated to Great Meadows and erected a defensive "Fort Necessity" to repel the French military response.

It was a poor tactical decision to stop rather than to keep retreating, and to build a fort at the chosen location. The French and their Indian allies attacked and Washington had to surrender. As part of the surrender, he signed a document in French (a language he did not read) that said he had assassinated de Jumonville.

The incident at what became known as Jumonville Glen helped to trigger the French and Indian War - or the Seven Years War, as it was known in Europe. The war was an imperial conflict that stretched from India to the Caribbean, and north to Canada.

Virginia officials were preoccupied with Washington's 1753 expedition and then in 1754 with preparing a "Force of Arms" to respond. The colony sent no commissioners to the June 19-July 10, 1754 Albany Congress championed by Benjamin Franklin.

Franklin saw the threat of French occupation of the Ohio River Valley. He was also concerned that the Susquehanna Company had organized in 1753 in Connecticut to occupy the Wyoming Valley. The colonial government of Connecticut claimed the land based on an 1662 charter in which King Charles II granted lands extending westward to the "Southern Sea."

Franklin proposed the colonies unite and form a common government in order to deal with the French threat. Consolidated colonial government would be led by a Grand Council, and the English king would appoint a President General comparable to a royal governor. In case that was not accepted, Franklin called for the creation of two new colonies in the northwest so English settlers would populate the region before the French.

Either one of Franklin's proposals could have ended the Virginia-Pennsylvania boundary dispute. A Grand Council could have made a decision on where to draw the line, or King George II could have done that when he chartered two new colonies. However, no colonial legislatures endorsed the recommendations of the Albany Congress.

Another 11 years passed before nine colonies organized another conference in New York to coordinate their responses to the Stamp Act. Virginia had no representative there either, but did send seven people to the 1775 Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

After the Virginians crossed into Pennsylvania and were forced to surrender at Great Meadows, King George II sent two regiments across the Atlantic Ocean to fight the French and defend colonial land claims.

General Braddock's 1755 expedition from Alexandria to the Ohio River was also a failure. His army was defeated by the French and their Indian allies. In the Battle of the Monongahela on the outskirts of Fort Duquesne, Braddock and the opportunity for Virginia to gain control the Forks of the Ohio both died.

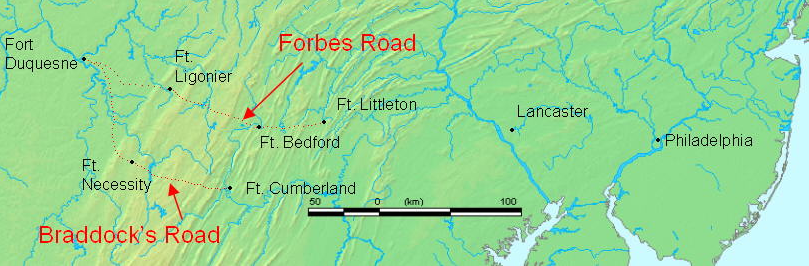

The British under John Forbes finally captured Fort Duquesne in 1758 and renamed it Fort Pitt. Much to the frustration of the Ohio Company and other land speculators in Virginia, Forbes' army in 1758 had been supplied from Philadelphia. His march westward from Carlisle across Pennsylvania established good roads that connected Philadelphia to the Ohio River. Forbes created a shorter, better road than the trail used by General Braddock on his expedition from Virginia.

As General Forbes reported back to London:11

Trade on Forbes' new road between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh undercut the Virginia colony's economic links up the Potomac River to the Ohio. If Braddock had captured Fort Duquesne and the Ohio Company had placed settlers in the Allegheny and Monongahela river valleys, Virginia might have established de facto economic and military control of the upper Ohio River Valley. If "possession is 99% of the law," then Virginia may have been able to repulse the legitimate land claims made by Pennsylvania based on the boundaries defined in Penn's 1681 charter.

Instead, Virginia's western boundary was reduced in the 1763 Treaty of Paris at the end of the Seven Years War. The French surrendered their claims to land on the North American continent. The Spanish ended up with Louisiana, including New Orleans. In the treaty, the Mississippi River was defined as the western edge of Virginia.

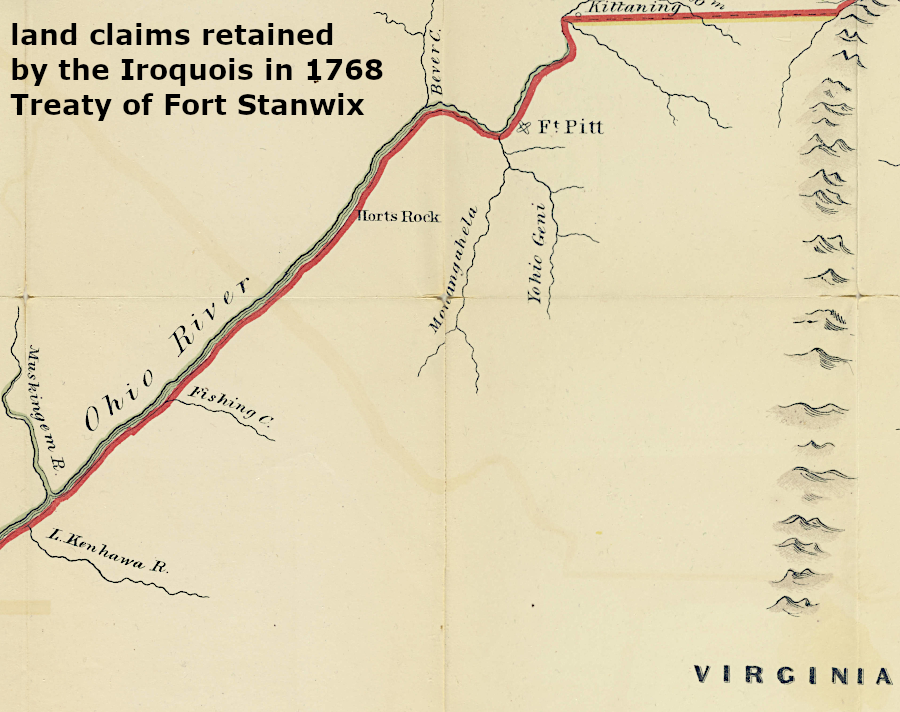

During the French and Indian War, Franklin's goal was achieved; the pacifist Quakers who had controlled Pennsylvania's government were replaced by assertive colonial leaders. The Penn family ended up paying the equivalent of taxes for defense expenses. The new colonial leaders ensured the Pennsylvania boundaries were established clearly, and acquired authorization from the Iroquois in the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix to expand settlement westward to the Ohio River.

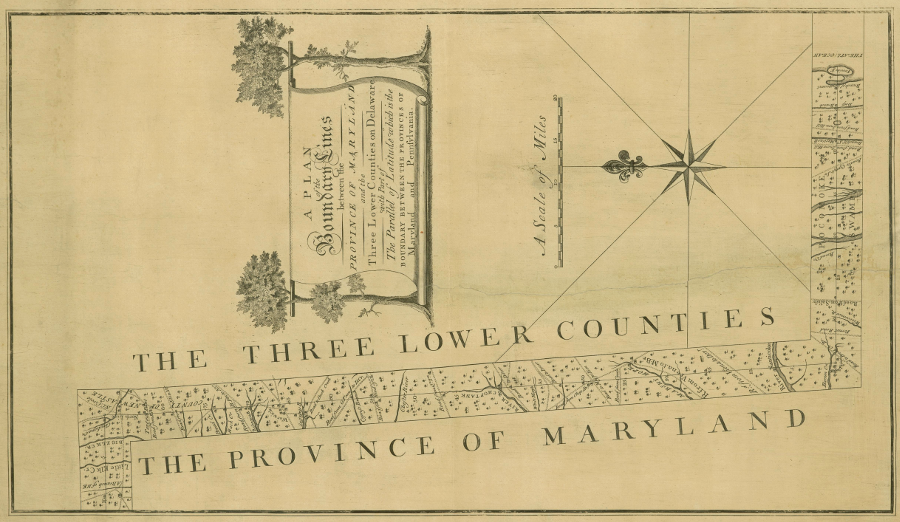

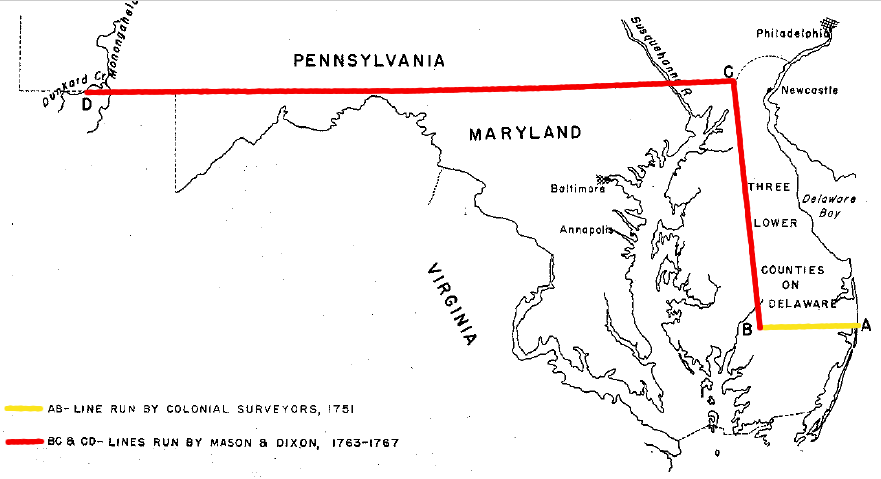

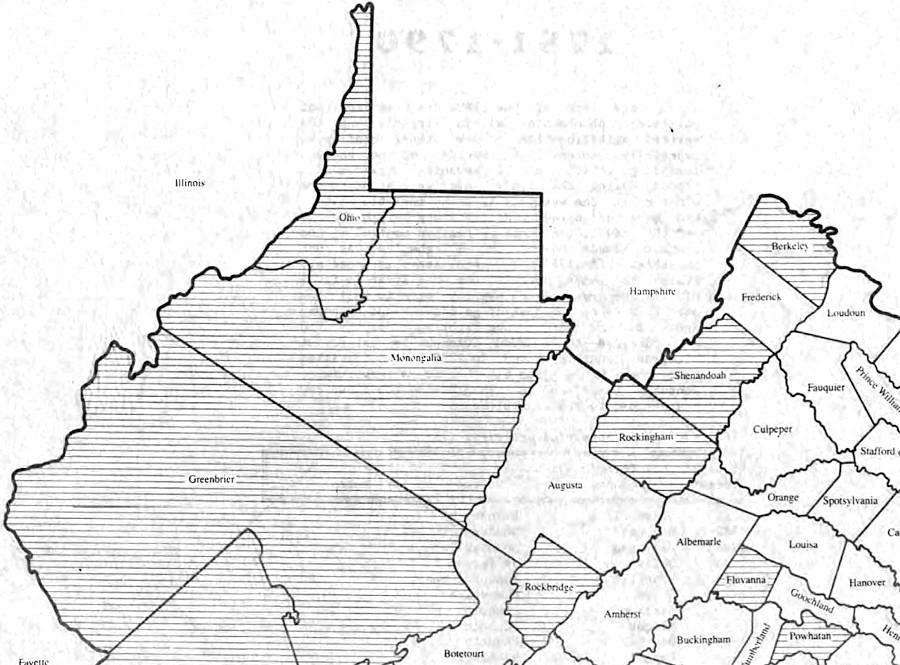

Pennsylvania and Maryland officials resolved their disputed boundaries before Pennsylvania and Virginia came to closure. Two Englishmen, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, surveyed a line in 1763-67 that became the southern boundary of Pennsylvania. Eventually, that line helped define the southeast corner of Pennsylvania - which became the Pennsylvania-Virginia boundary west of Maryland.

the original Lewis Evans map showed an extension of the Mason-Dixon line westward, serving as the Virginia/Pennsylvania border

Source: Library of Congress, A general map of the middle British colonies in America

Ever since the proprietary grant to William Penn in 1681, the border between Virginia and Pennsylvania had depended upon determining both the eastern edge of Pennsylvania and the southern boundary. The 40th degree of latitude was more than 12 miles north of New Castle, so the key location in Penn's charter to define his boundaries did not exist. Once the eastern and southern edges of Pennsylvania was resolved, however, surveyors could locate a north-south line "five degrees in longitude, to bee computed from the said Easterne Bounds" to mark the western edge of Pennsylvania.

colonial boundary claims of Pennsylvania vs. New York, 1755 (Pennsylvania extends to 43rd degree of latitude, but also extends south of 40th degree running through Philadelphia...)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the British and French dominions in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements

While the western boundary was still unclear, land speculators in Virginia chartered the Ohio Company, speculators in Pennsylvania chartered the Indiana Company, and speculators in Maryland formed the Illinois and Wabash companies. Their claims overlapped each other.

The French and Indian War delayed resolution of the Ohio Company's claims, which the Virginians had sought to clarify in 1749 through a proposed survey of colonial boundaries. When the war ended in 1763, the Calverts of Maryland and the Penns of Pennsylvania hired two "neutral" surveyors to define the southern boundary of Pennsylvania/northern boundary of Maryland - but not the Pennsylvania-Virginia boundary.

a map prepared after the end of the Seven Year's War accepted Pennsylvania's claim to lands west of Pittsburgh

Source: Library of Congress, An accurate map of North America (by Emanuel Bowen, 1763)

Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon spent four years (1763-1767) marking the location of the colonial boundaries with monuments on the ground. They started by identifying a spot 15 miles south of Philadelphia, setting a "Post marked West." That established a point of beginning, accepted by Penns and Calverts as the appropriate latitude for their dividing line.

In 1764 Mason and Dixon defined the western border of Delaware, separating it from Maryland. In 1765, the two surveyors returned to the "Post marked West" and began to pull the 66-foot chain to define more of the West Line. When they reached North Mountain at modern Hancock, they determined that Maryland would be two miles wide at that point.

Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon surveyed the boundary between Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia

Source: John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, A Plan of the Boundary Lines between the province of Maryland and the Three Lower Counties on Delaware (Charles Mason, 1768)

In 1766, they surveyed eastward from the "Post marked West" to the Delaware River. Penn's charter defined the western edge of the colony to be five degrees west of the eastern edge, and that point on the Delaware River ultimately determined the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania separating it from Virginia. Mason and Dixon also returned in 1766 to North Mountain and surveyed further west to Little Allegheny Mountain, the line today that separates Somerset and Bedford counties in Pennsylvania. Each mile, they set a monument stone to mark the boundary.

When Mason and Dixon surveyed the West Line in 1767, they soon reached a point due north of the headwaters of the Potomac River. Maryland's western border was defined by a north-south line between the "headspring" of the Potomac River (marked by the Fairfax Stone in 1746) on the south and the Mason-Dixon line on the north. West of the headspring, Mason and Dixon were no longer defining the Pennsylvania-Maryland boundary; they began defining the boundary between Pennsylvania and Virginia.

Mason and Dixon were paid by the Calverts and Penns to survey the boundary between Maryland and Pennsylvania, but continued past the western edge of Maryland and defined a portion of the Virginia-Pennsylvania border

Source: Maryland Board of Natural Resources, The Maryland-Pennsylvania and The Maryland-Delaware Boundaries (Figure 9)

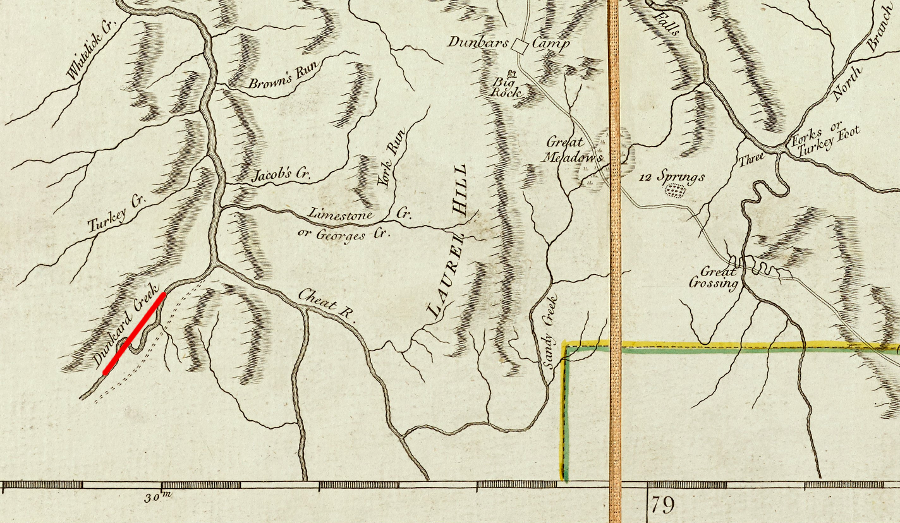

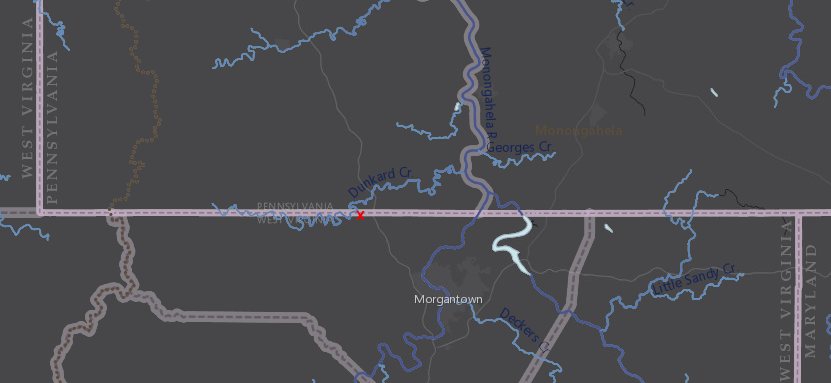

Mason and Dixon stopped work on October 9, 1767 at Dunkard Creek. After the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster, that stream marked the War Path of the Iroquois who traveled south to attack Cherokee and the Catawba.

The surveyors did not keep going west in order to complete the east-west line, the southern boundary of Pennsylvania. Surveying to the southwestern corner of that colony would establish the Virginia-Pennsylvania boundary. However, Mason and Dixon had finished the task assigned by the Penns and Calverts. More importantly, the Iroquois refused to provide protection west of their War Path against possible attack by Shawnee, Delaware and Mingo warriors.

Mason and Dixon stopped at Dunkard Creek, and did not survey to the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania

Source: John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, A map of Pennsylvania exhibiting not only the improved parts of that Province, but also its extensive frontiers (Robert Sayer and John Bennett, 1775)

Mason and Dixon finished 233 miles west of their point of beginning. Dunkard Creek is 33 miles west of the Maryland border and 22 miles east of the point that is now the southwestern edge of Pennsylvania. West of Sideling Hill, the surveyors used mounds of earth rather than stone monuments to mark the boundary between British colonies.12

portion of Mason-Dixon line delineating Maryland from Pennsylvania

Source: Library of Congress - Charles Mason, 1768,

A plan of the west line or parallel of latitude, which is the boundary between the provinces of Maryland and Pensylvania

The endpoint of the Mason-Dixon line was thought to be 36 miles east of the line that would be "five degrees in longitude... computed from the said Easterne Bounds." That left enough land to the west, and enough confusion about the boundary lines in the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania, for assertive and land hungry Virginians to claim the rights to property that may have been located in Virginia - or maybe not.

Mason and Dixon crossed the Monongahela River and quit surveying at Dunkard Creek

Source: Library of Congress - Charles Mason, 1768,

A plan of the west line or parallel of latitude, which is the boundary between the provinces of Maryland and Pensylvania

the western end of the Mason-Dixon Line is north of modern Morgantown, West Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Native American attacks during the French and Indian War and then Pontiac's War forced abandonment of farms, but by 1764 settlers raced to occupy western lands again. They ignored British and colonial officials who issued multiple proclamations directing them to leave, anticipating that at some point their claims to land would be officially authorized. The squatters could sell products at Fort Pitt to the British army, or ship downstream to the Spanish on the Mississippi River.

A year after the Iroquois signed the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix and relinquished claims east/south of the Ohio River, Pennsylvania opened a land office and began to authorize surveys and sale of lands in the western part of that colony. The Penns reserved land for proprietary "manors" at the Forks of the Ohio and at Kittanning, but the rest of the region was available for purchase. Individual surveys were limited to 300 acres, and the price was set at five pounds per 100 acres. Virginia officials allowed people to acquire 1,000 acres at a time.

Many of the unauthorized settlers came from Virginia. In Williamsburg, officials continued to assert that the Forks of the Ohio were within their colony and not in Pennsylvania. Land speculators associated with the Ohio Company asserted their right to sell land south of the Ohio River up to the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers.

Virginians also acquired land which they expected to be within Pennsylvania. In the Proclamation of 1763, the royal government authorized land grants to those who fought in the French and Indian War. That land bounty was independent of the 200,000 acres previously promised by Governmor Dinwiddie in 1754 to recruit 300 men to march to the Forks of the Oghio and defend the Ohio Company fort being built there by William Trent.

Under King George III's offer in his 1763 proclamation, officers such as George Washington were entitled to 5,000 acres for their service. After the war, Washington purchased the rights of other veterans. He paid a discounted value, recognizing that the survey and patenting of the land grants would take years to finalize.

In 1767, Washington asked surveyor William Crawford to identify a tract of 1,500 or more acres on the Youghiogheny River. "Washington’s Bottom" was his first land acquisition on the west side of the Allegheny Front. That claim was clearly in Pennsylvania.

Crawford and Washington finessed Pennsylvania's limit of 300 acres per parcel by dividing a 1,644 acre claim into five surveys. Four other purchasers immediately transferred their ownership to Washington; a process which was common at the time. One indication of the complexities of the process, including the interruption of court procedings by the American Revlution, is that the land patent for Washington’s Bottom was not finally issued until 1782.

The Walpoles and other land speculators based in Philadelphia organized the claims of the "suffering traders" impacted by Pontiac's War. That group sought to bypass the inter-colonial dispute and supersede any Virginia claims. A land grant from King George III for Indiana, later expanded into the 20,000,000 acre Vandalia grant, would give the Indiana Company/Grand Ohio Company legal right to sell much of the land between the Appalachians and the Ohio River. The Vandalia claim overlapped claims of the Ohio Company and many others.

Back in 1749, trader and interpreter George Crogan had gotten Iroquois chiefs to give him the rights to 200,000 acres in the Ohio River Valley. Crogan was a negotiator between British/colonial officials, other traders, and Native American groups in western Pennsylvania. Starting in 1756, he served underneath Sir William Johnson as Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Department.

His claim to the land had thin justification; British and colonial policies prohibiting recognition of private land sales by Native American tribes. Despite the prohibition, Crogan repeatedly asserted in various settlings that he was entitled legally to the 200,000 acres. In the absence of clearly legitimate authority by either Pennsylvania or Virginia to sell land and guarantee title, Crogan proceeded to open a land office in 1770 and convinced some settlers to pay him for land around Fort Pitt.

Land ownership in the area was complicated by the actions of Lord Dunmore in Williamsburg. In 1773 he authorized a surveyor, William Bullitt, to mark off parcels so Virginia could start awarding the land grants promised to soldiers in the 1763 Proclamation.

The 1749 Ohio Company grant and the 1749 claim made by George Crogan conflicted with the 200,000 acres that Governor Dinwiddie set aside on the Ohio River to recruit men willing to join the military force he sent to the Forks of the Ohio in 1754.

In addition, efforts to transfer legal title were complicated by the Proclamation of 1763. It prevented Williamsburg-based officials from approving surveys and patenting land west of the Appalachians; the Ohio River watershed was off-limits whether or no the land was in Virginia or Pennsylvania.

Washington purchased 15,000 acres near the Forks of the Ohio. Land surveys there overlapped with each other, including George Crogan's surveys; getting clear title was not a simple process. Settlers would have to choose who they would pay for legal title to land, eventually.

Most settlers moving into the Ohio River watershed, in violation of the Proclamation of 1763, chose to squat and start a farm without having any survey done. Early settlers planned to wait and, if a tomahawk or preemption claim was not sufficient, pay for the land once it was clear how to establish legal title. Paying George Crogan, George Washington, or some other Virginian for land might be a waste if a parcel ended up within the boundaries of Pennsylvania. In that case a Virginia patent would be worthless; a new survey and new payment would have to be processed by a Pennsylvania land office:13

Virginia officials and land speculators claimed the Forks of the Ohio had been seized by the French and recaptured by the British army under General Forbes in 1758, extinguishing the border as defined in Pennsylvania's 1682 charter. If the western boundary of the Pennsylvania charter ever extended beyond Fort Pitt, Virginians highlighted that the British army had conquered the western lands in the French and Indian War. Under the Right of Conquest, the old Penn family rights to the territory had been wiped out. The 1763 Treaty of Paris gave King George III ownership, and under his authority Virginia governors could grant clear title to Virginia settlers.

a jagged western boundary (green line) would have given Virginia much of southwestern Pennsylvania but not Fort Duquesne

Source: Library of Congress, A map of Pensilvania, New-Jersey, New-York, and the three Delaware counties (by Lewis Evans, 1776)

Philadelphia-based land speculators competing with Virginia land speculators sought to obtain rights to land along the Ohio River through British officials in London. The Philadelphia speculators acquired the claims of "suffering traders" whose goods shipped to backcountry trading sites, had been seized by Native Americans and their French allies at the start of the French and Indian War or during Pontiac's War in 1763.

In the negotiations that led to the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Iroquois agreed to compensate the suffering traders with rights to "Indiana," a large chunk of land somewhere west of the Monongahela River. That treaty also ceded to the British government the questionable Iroquois claim to land south of the Ohio River, clearing title to Kentucky for Virginia's land speculators such as the Loyal Land Company and the Ohio Company. However, the 1768 treaty did not cede to the British any of the Native American claims to land north of the Ohio River, and the 1763 Proclamation Line still banned settlement west of the Allegheny Front.

the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix did not authorize settlement west of the Ohio River by people from either Virginia or Pennsylvania

Source: Penn State, Map of the frontiers of the northern colonies : with the boundary line established between them and the Indians at the treaty held by S. Will Johnson at Ft. Stanwix in Novr. 1768

The attempt to establish Indiana, which investors eventually transformed into the proposal for the Vandalia colony, was in direct conflict with the 1749 grant issued in Williamsburg to the Ohio Company. Virginia investors in the Ohio Company had the right to 500,000 acres of western land located south of the Ohio River

Pennsylvania-based land speculators outmaneuvered the Virginians in London and in 1773 got initial authority from the Privy Council to create Vandalia. The Ohio Company investors decided to join rather than fight the Walpoles and others from Philadelphia. The Ohio Company investors ended up owning only two of the 72 shares, but that would have totaled over 500,000 acres because the Vandalia group ended up asking for 20,000,000 acres of land in what today is West Virginia and Kentucky. Unfortunately for the Pennsylvanians and the Ohio Company, the American Revolution eliminated all British-approved claims to Vandalia and the colony never opened the planned land office at Fort Pitt.13

After the French left North America in 1763, Fort Pitt was no longer on the edge on an international frontier. The star-shaped fort had been built between 1759-1761 with 15' high massive walls. The eastern edge was covered with brick to withstand a long siege by a French army firing cannon from the land approach. During floods in 1762 and 1763, floodwaters reached 40' high and two of the five bastions were ruined.

Repair was not needed; the French threat disappeared when Great Britain acquired Canada and all lands west to the Mississippi River in the 1763 Treaty of Paris. The Native Americans who besieged the fort during Pontiac's War in 1763 had no cannon. Fort Pitt's primary function after 1763 was to serve as a supply base to support Fort Chartres on the Mississippi River.

From a military perspective, Fort Chartres defended the western edge of British territory; just across the Mississippi River was Spanish Louisiana. The British anticipated that Fort Chartres would attract settlers. Economic development, starting with British control of the fur trade, would offset the costs of protecting the western lands won in the French and Indian War.

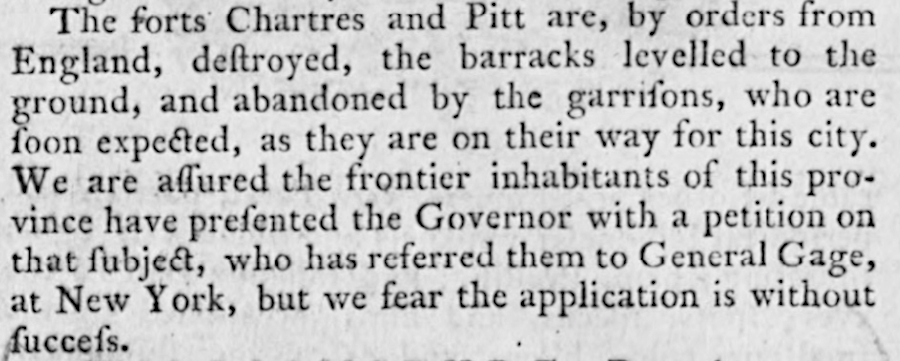

Fort Chartres failed to become self-sufficient. The fur trade to Montreal was now controlled by British merchants, but the fort itself was expensive to staff with Regulars. After General Gage, the British commander in North America, was directed to reduce costs of the military bases, he recommended in 1771 closing Fort Chartres and Fort Pitt. Officials in London concurred, and both Fort Pitt and Fort Chartres were abandoned in 1772.

Before completing total demolition of the fortifications at Fort Pitt, the British officer in charge sold it to Alexander Ross and William Thompson. They planned to salvage usable building materials, particularly materials such as the bricks on the eastern front. The Ohio Company then acquired control.

Between 1763-1775, the annual cost of the British military establishment equaled about 4% of the total annual budget - a high enough figure to generate pressure for the colonists to pay their "fair share" of defense costs. Such a policy is not unusual. In modern times, the United States began to pressure its North American Treaty Organization (NATO) allies to increase their defense spending even before Russia's 2021 invasion of Ukraine in order to offset the burden on American taxpayers.

Parliament passed a series of taxes, including the 1764 Sugar Act, 1765 Stamp Act, and the 1767 Townsend Acts, in order to raise revenue so North American colonists paid at least some of the costs of their military defense. Parliament also succeeded in getting the British Army to reduce the costs of maintaining troops in North America.

At the end of the French and Indian War, all provincial troops such as the Virginia Regiment were disbanded. Great Britain still had 10,000 Regulars in North America, including Canada, Florida and the sugar islands in the Caribbean. In the 13 colonies, troops were stationed in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and New Jersey plus western forts such as Fort Pitt.

The number of Regulars was reduced to about 7,500 between 1765-1770. Further reductions, both in battalion size and the number of forts, lowered the total to 6,200 soldiers by 1773. Spending peaked in 1770, a year in which many when old bills were paid, at £424,609. The cost of the North American "establishment" dropped to £,340,457 in 1773.

news from Philadelphia reached Williamsburg in December, 1772 that the British Army had abandoned Fort Pitt and Fort Chartres

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Virginia Gazette (December 3, 1772, p.2)

The withdrawal of the British army from Fort Pitt left a vacuum that both Virginia and Pennsylvania tried to fill.

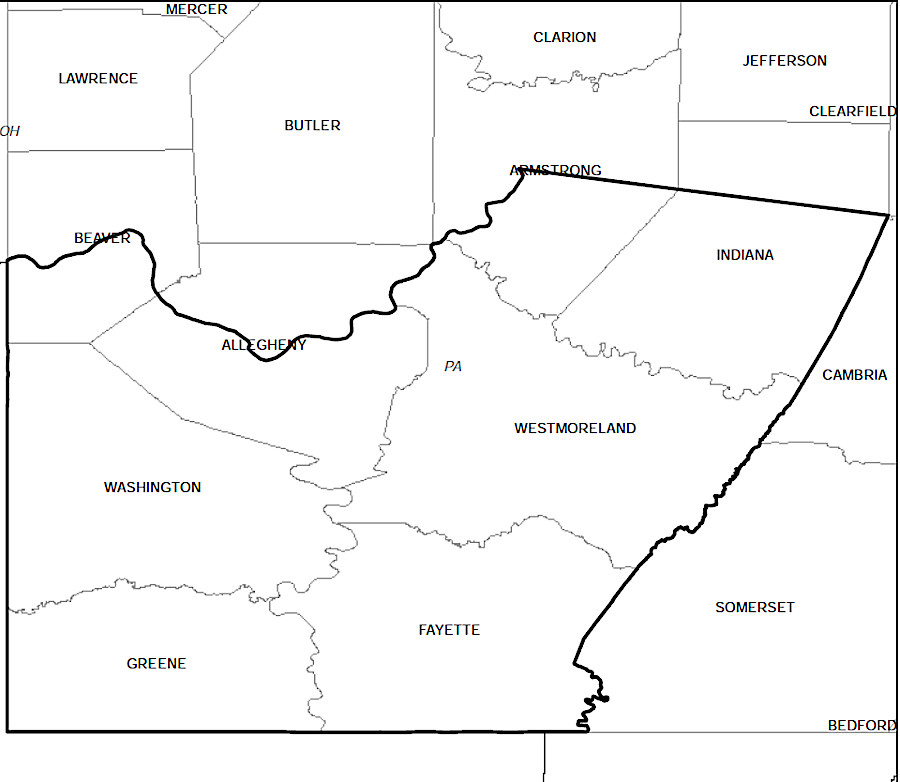

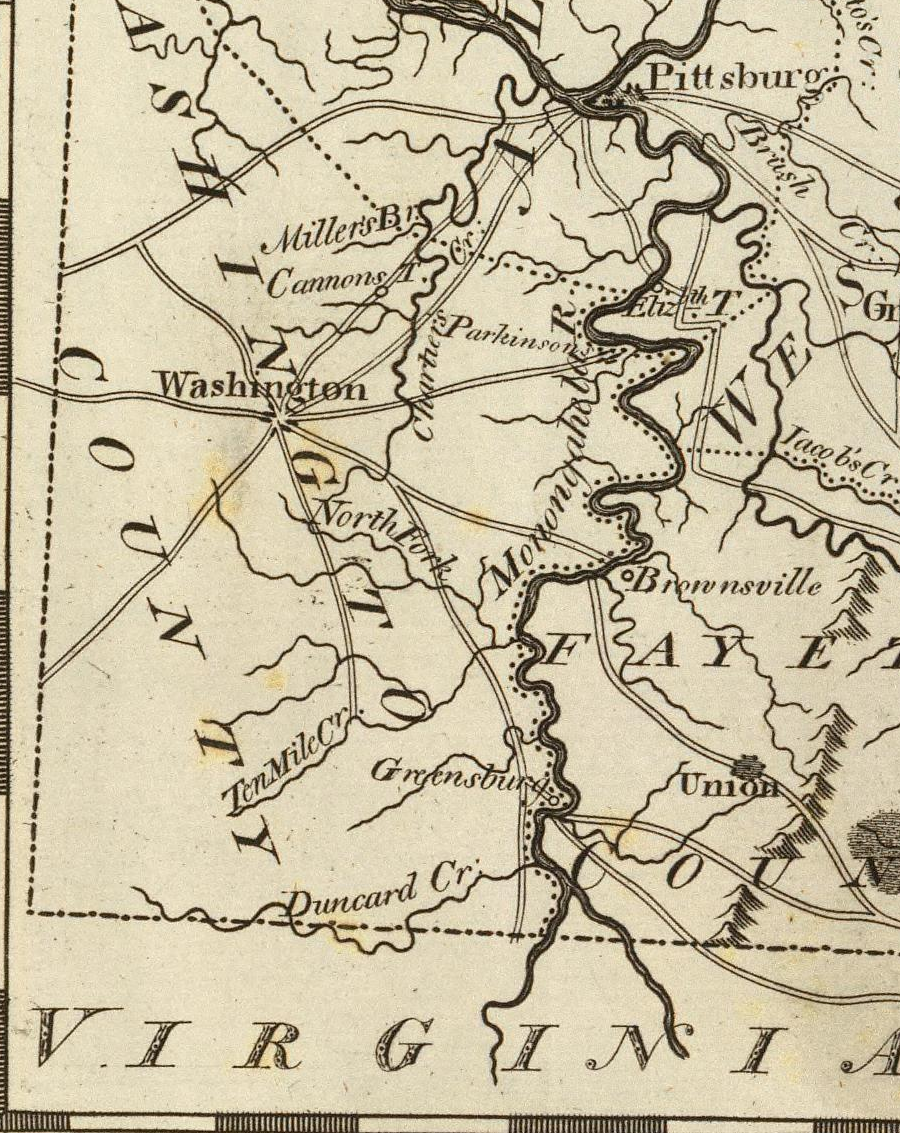

Pennsylvania created Westmoreland County on February 26, 1773. That action established, in the southwestern corner of the colony, a local court that could process surveys and land patents. Settlers loyal to Pennsylvania seeeing title to land could deal with local officials appointed by the Pennsylvania General Assembly, or elected locally in Pennsylvania-sponsored elections. Surveys and claims processed by Virginia officials could be ignored.

creation of Westmoreland County in 1773 enabled Pennsylvania to issue legal title to land around Pittsburgh

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

In 1773, Governor Dunmore traveled from Williamsburg to Fort Pitt. He was welcomed by settlers from Virginia who were threatened by both Native Americans and Pennsylvanians.

The royal governor had planned to travel to the Ohio River in 1773 with George Washington. They were going to see land that could be granted to French and Indian War veterans and to land speculators such as Washington who had purchased their warrants. Dunmore was also aware that many of the leaders in Virginia were involved with land companies seeking authorization to complete surveys and sell parcels based on grants to the Ohio Company dating back to 1749.

Also in 1773, Thomas Bullitt took a team down the Ohio River and completed surveys. He and Washington anticipated that Governor Dunmore would find a way to finesse instructions from London that were blocking land transfers west of the line identified in the Proclamation of 1763. Virginia speculators hoped to get patents signed by a Virginia governor; official title would allow sale of land near the Forks of the Ohio despite Pennsylvania's boundary claims.

Governor Dunmore arrived at Fort Pitt, without Washington as a traveling companion, in the summer of 1773. George Washington's step-daughter Patsy had died; that forced him to cancel plans to leave his wife Martha and step-son Jackie. As a result, Washington missed his chance to lobby Dunmore for many days while riding to Fort Pitt and then further west across the Ohio River.

At Fort Pitt, Dunmore quickly hired Dr. John Connolly as his land agent. Connolly could interpret for those seeking to negotiate with various Native American groups, and was very familiar with the region. For payment, Dunmore promised to provide Connolly a grant of several thousand acres.

John Connolly wrote George Washington from Pittsburgh in June, 1773, saying that Dunmore had promised him a grant of 2,000 acres at the falls of the Ohio (modern day Louisville, Kentucky) and that Thomas Bullitt had surveyed a parcel for Connolly's claim. On October 10, 1773, Dunmore signed a 2,000 acre patent for Connolly. Issuing a final patent to lands west of the 1763 Proclamation Line was a rare event.

Washington wrote to Dunmore in September, 1773 that he had considered using his French and Indian War claims to acquire land in West Florida instead of along the Ohio River, but discovered he was too late. Those lands were "...not to be had; being entirely engross'd by the Emigrants which have lately gone there to Settle."

Washington suggested to Governor Dunmore that Pennsylvania officers had already laid claim to 300,000 acres. In a later letter to William Crawford, Washington wrote:14

The Virginia governor, still conscious of directions from London but seeking to establish his own claims to western lands, was inconsistent in his actions. In 1773 he forced a survey party (separate from Thomas Bullitt's) to leave the Ohio River Valley in order to avoid triggering conflict with the Shawnee living there. Despite his approval of a patent to Dr. John Connolly, Governor Dunmore told Washington after visiting Fort Pitt:15

After getting back to Williamsburg in September 1773, Dunmore declared bluntly that Virginia controlled the area around the forks. On October 11, 1773, the Virginia General Assembly carved the District of West Augusta out of Augusta County. The district boundaries incorporated lands westward to the Ohio River and north to Fort Pitt. The "district" label may have been intended to minimize objections from the king's ministers in England.

Creating the Augusta District initiated a legal framework to permit a county surveyor to authorize surveys and eventually authorize transfer of Ohio River lands to Virginians. Technically the colonial legislature did not create a "county" that might violate the Proclamation of 1763. The Western Augusta District was a warning to Pennsylvania land speculators, but its creation did not translate into the action most desired by those seeking legal title to land. The colonial land office in Williamsburg still needed to approve surveys, and the governor still needed to sign patents.

the District of West Augusta lasted just two years

Source: e-WV, The West Virginia Encyclopedia Online, West Augusta

On January 1, 1774, Dr. John Connolly and a band of armed Virginia seized control of Fort Pitt and renamed it Fort Dunmore. Governor Dunmore appointed him "Captain, Commandant of the Militia of Pittsburgh and its Dependencies." Most residents of Pittsburgh were supporters of the Virginia claim to control the area. Organizing a Virginia militia at Pittsburgh would help them obtain Virginia title to what was supposedly Virginia land.

The Augusta county court was scheduled to hold its first meeting at Fort Dunmore on January 25, 1774. A day prior to that meeting, Westmoreland County (Pennsylvania) officials arrested Connolly. They released him from jail after he promised to come back to their court in April, 1774. Connolly did return, but he brought nearly 200 Virginia militia with him. He arrested two Westmoreland County justices and incarcerated them at Pittsburgh.

Governor Penn in Philadelphia sent commissioners to Williamsburg to resolve the boundary conflict. They arrived on May 19, 1774 as the General Assembly was becoming radicalized by the Coercive Acts. In response to the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, Parliament had decided to close the port of Boston starting June 1, 1774. Using the Royal Navy to bankrupt the merchants in Massachusetts was expected to frighten the leaders in other colonies and prevent them from aligning with Massachusetts,.

Instead, British retaliation spurred enhanced cooperation among 13 of the British colonies in North America. Members of the Virginia House of Burgesses recognized that inter-colonial cooperation was essential to altering British policy. A sense of common purpose among 13 colonies, opposed to arbitrary decisions by Parliament and King George III, ended up being created through Committees of Correspondence.

The Pennsylvania officials in Williamsburg proposed the two colonies appoint a team of surveyors to draw a western boundary that would be parallel to the curves of the Delaware River, bending back and forth five degrees to the west. Their second proposal was to set the Monongahela River as the western boundary of Pennsylvania. Governor Dunmore proposed a line that he thought would be 50 miles east of Pittsburgh.

The commissioners could not resolve the Pennsylvania-Virginia boundary issue in 1774. The land was too valuable, too many top officials in each colony had a personal stake in the potential for gaining private wealth based on how the boundary was defined, and the need to unite the colonies against Parliament and KIng George III was not yet urgent enough to overcome inter-colonial rivalries.

The timing of the discussion constrained the ability of the House of Burgesses and the Governor's Council to engage in negotiations. Governor Dunmore dissolved the House of Burgesses soon after the Pennsylvania delegation arrived. The burgesses then focused on establishing a parallel government structure for Virginia over which the royal governor had no control, starting with a Virginia Convention in August 1774. That convention selected the colony's delegates who attended the first Continental Congress starting in September, 1774.

Connolly was arrested and sent to Fort Ligonier. His allies at Fort Dunmore responded by arresting local Pennsylvania justices. On June 22, 1774 the sheriff of Westmoreland County led a force of men to Pittsburgh and freed the Pennsylvania justices.

Supporters of Connolly ended up sending three Westmoreland County justices to Staunton. One then went to Williamsburg and talked with Governor Dunmore. The governor ordered the Pennsylvania justices to be released, but affirmed that Connolly was acting under his orders and that civil government at Fort Pitt was a responsibility of Virginia:16

As the officials around Pittsburgh were being arrested and released, Governor Dunmore left Williamsburg to lead an army against the Shawnee in what became known as Dunmore's War. He left town before the first Virginia Convention convened on August 1 at the Capitol. That unauthorized meeting began the process of degrading royal authority, which as a side effect prevented any resolution of colonial boundary issues.

Dunmore went to Pittsburgh in August 1774 and raised troops to march against the Shawnee. While in Pittsburg on September 17, he declared that the Virginia government based in Williamsburg was responsible for all lands west of Laurel Ridge. After defeating the Shawnee, Mingo, and Delaware warriors and negotiating the Treaty of Camp Charlotte, Governor Dunmore returned to Williamsburg. On December 6, he ordered the Augusta County Court to hold sessions in Pittsburgh as well as in Staunton.

The Frederick County militia led by Colonel John Neville arrived at the start of 1775 and renamed Fort Pitt as Fort Dunmore. At this time, Dunmore was the colony's legitimate top official and had just defeated the Shawnee in Lord Dunmore's War. The first Augusta County court session help at Fort Pitt started on February 21, 1775.

Pennsylvania sent commissioners to Williamsburg in May, 1774, but resolving the boundary issue became a secondary concern as Virginia leaders focused on countering the Coercive Acts

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Virginia Gazette (May 26, 1774, p.2)

The Augusta justices appointed by Governor Dunmore quickly incarcerated two Westmoreland County justices for their refusal to accept Virginia's authority. They were not freed until June, 1775 at which time Connolly was arrested and jailed by Westmoreland County officials.

Connolly was released and returned to Pittsburgh. His supporters there then arrested three more Westmoreland County justices and sent them down to Fort Fincastle, the site of modern Wheeling, West Virginia.

The Second Virginia Convention in April 1775 called for creation of independent militia companies which would owe no allegiance to royal officials. Those independent companies elected their own officers and had no responsibility to obey anyone appointed by Governor Dunmore.

Connolly left Pittsburgh in July, 1775 and rode to Williamsburg. By then, he was being recognized as a loyalist. Without a Virginia militia force in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania officials filled the void. That colony gained more control as the potential for armed conflict with British Regulars became more clear and then started at Lexington and Concord on April 9, 1775.

Connolly may have chosen to remain loyal to Great Britain because he was expecting great influence and rewards from his close relationship with Governor Dunmore. Had the British won the war, the Grand Ohio Company's dream of obtaining the 20,000,000 acre grant of Vandalia might have been realized. Connolly might have gained a large personal land grant for his services to King George III.

After arriving from Pittsburgh, Connolly met with Governor Dunmore on his ship, anchored off Norfolk. He then traveled to Boston and shared their plan with General Thomas Gage. Connolly was responsible for organizing a Native American attack on the western edge of the rebellious colonies. After capturing Pittsburgh, that army was expected to march to the Potomac River, seize Wills Creek (Cumberland, Maryland), then rendezvous with Dunmore to attack Alexandria.

After General Gage concurred with the strategy, Connolly sailed from Boston back to Portsmouth to report to Governor Dunmore. A man that Connolly had considered to be a reliable co-conspirator went ashore in Newport, Rhode Island. He alerted George Washington of the plans of Connolly, Dunmore and Gage to organize an attack on Virginia from the west.

He then went up the Potomac River and traveled through Maryland, trying to reach Pittsburgh. Once he reached the banks of the Ohio River, he planned to assemble an armed force and mobilize Native American allies.

However, while headed from Hagerstown to Pitsburgh, Connolly was recognized in November 1775 by a man who had served under him in the Virginia militia. He saluted his former commanding officer. Soon after, Marylanders who were no longer loyal to the Crown arrested Connolly.

He spent the Revolutionary War in a Philadelphia jail until being exchanged in 1780. He joined General Cornwallis in Virginia, slipping out of the British lines at Yorktown before the siege began. Connolly was arrested again and kept in prison in Virgina until March, 1782.

He ended up in the British-occupied fort at Detroit after the war, where he tried to organize resistance to the Americans. Before the British surrendered the western forts, he sought to get settlers in Kentucky to ally with Great Britain or Spain and separate from the United States.17

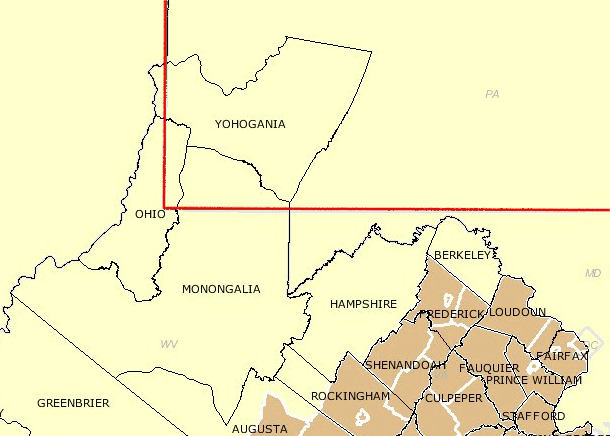

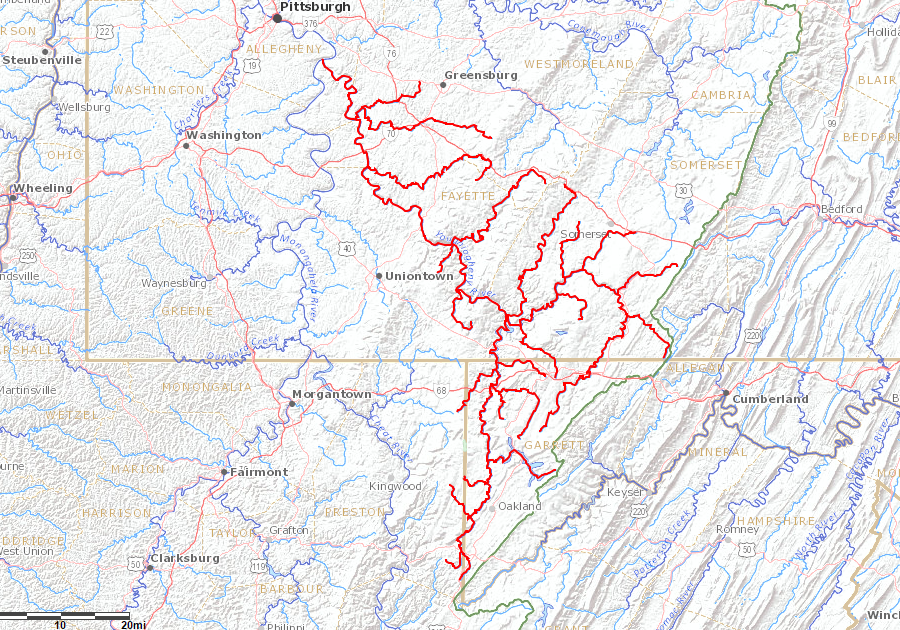

trespass of Yohogania, Monongalia, and Ohio counties into Pennsylvania

Source: Newman Library - Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

As a result of the overlapping Pennsylvania and Virginia claims and the actions of Dunmore and Connolly:18

the District of West Augusta, created in 1775, was carved up into three counties in 1776: Yohogania County (in red), Monongalia County (in green), and Ohio County (in blue)

Source: The Boundary Controversy between Pennsylvania and Virginia, 1748-1785, by Boyd Crumrine in Annals of the Carnegie Museum, Vol. 1 (1901) (opposite p.518)

Overlapping jurisdiction meant that property rights were very, very confused. One scholar has noted:19

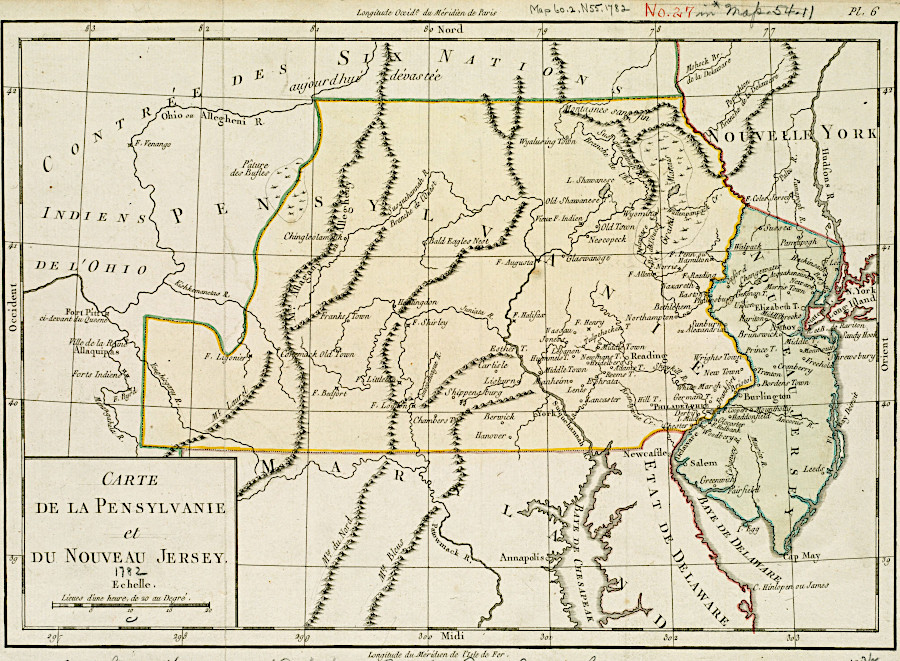

whether Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) was in Pennsylvania or Virginia was in question, until the two states settled their boundary dispute

Source: Boston Public Library, Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Carte de la Pensylvanie et du Nouveau Jersey (by Michel-Rene Hilliard d'Auberteuil, 1782)

in 1776, Virginia and Pennsylvania made competing proposals at the Continental Congress for locating a temporary boundary

Source: Library of Virginia, Resolution regarding the Pennsylvania-Virginia boundary, 1776 June 15

The continuing conflict among states which were supposedly uniting to fight the British was a concern to the Continental Congress, as was the difficulty created in managing relations with Native American tribes on the frontier.

Settlers in the area petitioned the Continental Congress to create a new state of Westsylvania. Creating a new state would resolve who was able to issue legal land titles. That request was similar to efforts by residents in western North Carolina to create the State of Franklin, a separate jurisdiction independent from both Virginia and North Carolina. Virginia, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina were able to block the creation of Westsylvania and Franklin and retain their western land claims.

After declaring independence, Virginia no longer needed to appease British officials,. The General Assembly formally created three separate counties (Yohogania, Monongalia, and Ohio) to replace the District of West Augusta, effective November 8, 1776.

The Virginia militia left Pittsburgh and the Continental Army garrisoned the town after September, 1777. George Washington deftly avoided getting involved in the boundary dispute. In 1779 he sent instructions to a military officer to prepare to attack the Iroquois, and included:20

mapmakers right after the American Revolution were vague regarding the western boundaries for Virginia and Pennsylvania

Source: Library of Congress, The United States of North America, with the British & Spanish territories according to the treaty (by William Faden, 1783)

In December, 1776 the Virginia General Assembly proposed that Pennsylvania's western boundary should mirror the bends and curves of the Delaware River. Mapping such a complicated boundary in the middle of the American Revolution would have been challenging.

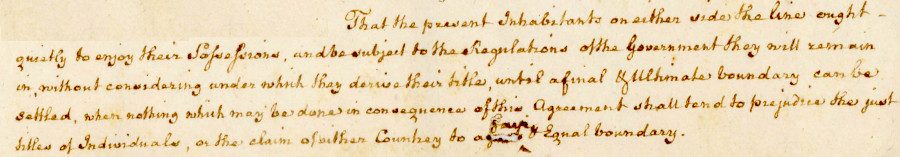

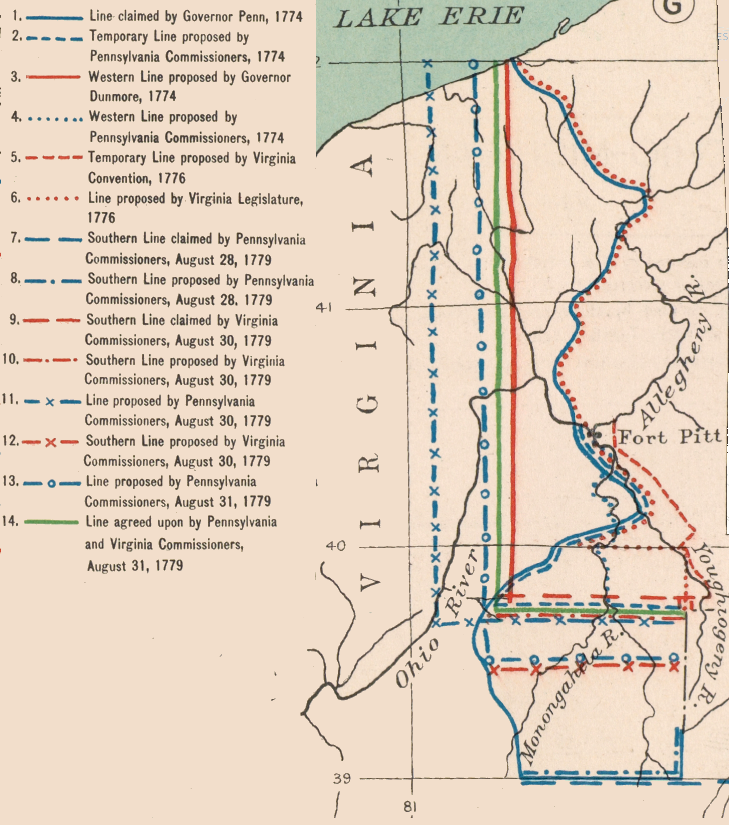

In 1779, Pennsylvania and Virginia appointed commissioners to negotiate a deal. They met in Baltimore, mid-way between each state on "neutral" ground.

Pennsylvania attempted to move the line south to the 39th parallel of latitude. Virginia sought to move the boundary north of the Mason-Dixon line to the 40th parallel. Both ideas were dropped when the commissioners agreed to use the line already defined by Mason and Dixon. The southern boundary of Pennsylvania would stop at a point five degrees west of the Delaware River, at a location beyond where Mason and Dixon had ended their survey but at the same latitude. From the southwest corner, a line would be surveyed straight north - without any wiggles to match the Delaware River on the eastern edge of the state.

In November 1782, surveyors maked a temporary line as far north as the Ohio River. Two years later, surveyors completed a permanent line for the southern boundary. In 1785, the north-south line to the Ohio River was finalized. A year later, after resolving conflicts with other states over ownership of the Erie Triangle, Pennsylvania completed surveying the western boundary line to Lake Erie.

Before ratifying the negotiated deal, Virginia insisted that pre-existing land claims by individuals be protected. Pennsylvania agreed to accept Virginia titles, provided that no earlier claim could be proved by a Pennsylvania resident. Based on the final 1780 agreement between the two now-independent state governments, Virginia eventually certified 1,182 claims for 534,371 acres. Most of the land in Washington County was patented based on Virginia certificates to settlers who arrived via Braddock's Road.

multiple proposals were made between 1774-1779 for defining Pennsylvania's border with Virginia

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Pennsylvania-Virginia Boundary (Plate 97g) digitized by University of Richmond

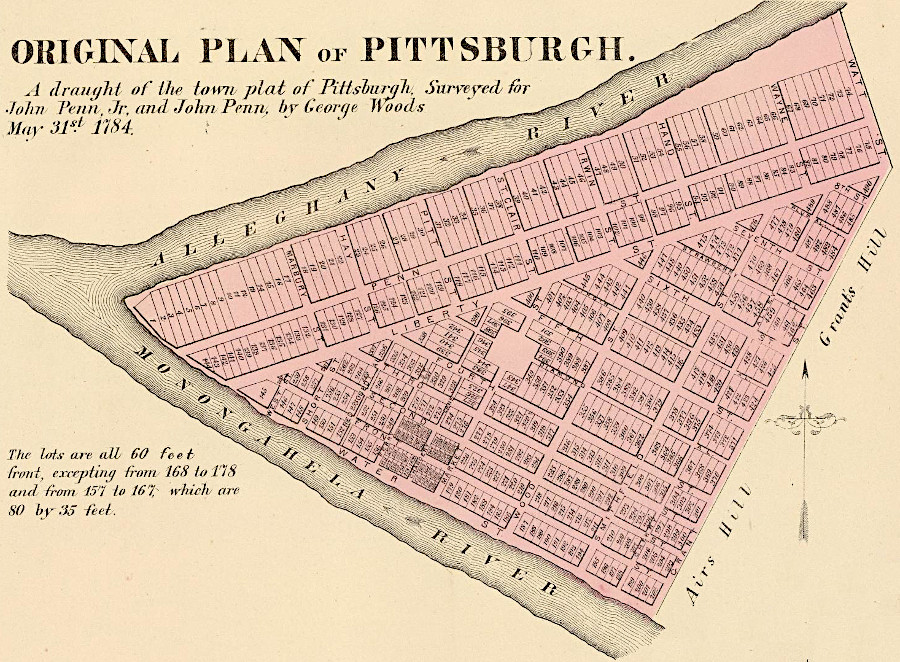

An official Pennsylvania survey of Pittsburgh lots was completed in 1784, enabling residents to obtain clear title to where they already lived. The surveyor had planned to create wider streets in the town, but the existing settlers were unwilling to be displaced.21

Pittsburgh residents could finally obtain clear title after the town was officially surveyed in 1784

Source: David Rumsey Map collection, Original plan of Pittsburgh. A draught of the town plat of Pittsburgh (by George Woods, 1784)

The western extension of the Mason-Dixon line was surveyed initially by Alexander McClean of Pennsylvania and Joseph Neville of Virginia in 1782. That survey was done after General Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown, but while Britain and America were still officially at war.

From the western endpoint of the extended Mason-Dixon line, the commissioners decided that the western edge of Pennsylvania (the boundary with Virginia) would be a straight line running north. If the western edge had paralleled the eastern boundary of Pennsylvania following the Delaware River, then the Virginia-Pennsylvania boundary north of the extended Mason-Dixon line would have curved back and forth as well. Because the Delaware River curved eastward at the latitude of the Forks of the Ohio, Fort Pitt would have become part of Virginia again.

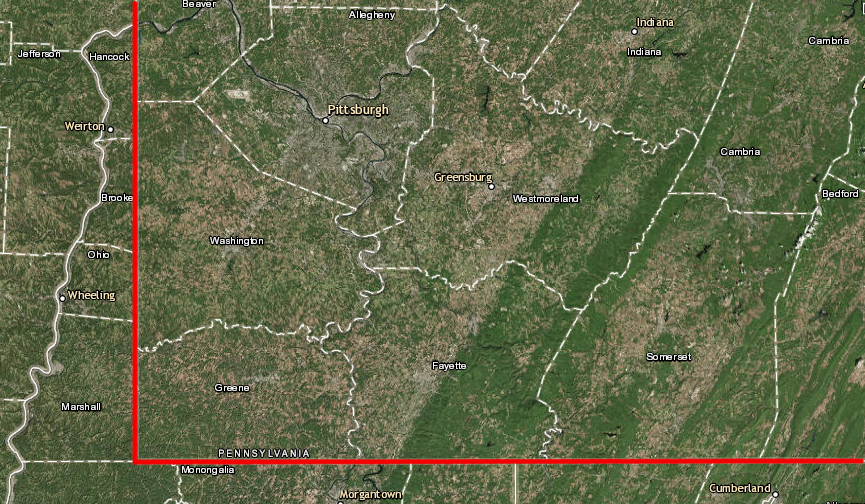

The straight north-south boundary resulted in Pennsylvania taking control of what are now portions of Washington, Greene, Fayette, Westmoreland and Allegheny counties.

Pennsylvania ended up with less territory than it initially claimed on its northern, eastern, and southern boundaries, but on the western boundary the final straight north-south line (unlike the proposed boundary shown above) expanded its size

Source: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, Pennsylvania, Maryland And Virginia (by Emanuel Bowen, 1758)

Pennsylvania also ended up with control of the transportation corridor between the Susquehanna and Ohio rivers, including the road cut by General John Forbes in 1757 in the campaign to expel the French from Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh). Virginia ended up with control of much of the transportation corridor between the Potomac and Ohio rivers, and ultimately built turnpikes and railroads that reached the Ohio River at Parkersburg and Wheeling. However, much of the road cut by General Braddock in 1755 ended up inside Pennsylvania.

the boundaries of Pennsylvania ended up giving that state control over land and water access to the Forks of the Ohio (Pittsburgh)

Source: Wikipedia, Forbes Road

If the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal had built past Cumberland and wanted to use the Youghiogheny River as the pathway to the Ohio River, then Maryland and Virginia would have needed approval from Pennsylvania. That state's legislature may not have wanted to enhance the ability of the ports of Alexandria and Baltimore to compete for trade with Philadelphia.22

the Youghiogheny River offered one possible route for the C&O Canal to reach the Ohio River

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

After the Virginia-Pennsylvania boundary was defined, including the north-south line defining the western edge of Pennsylvania, Virginia altered the boundaries of two counties. The eastern edges of Monongalia and Ohio counties were revised, reducing the size of those jurisdictions and excluding the land that was located east across the boundary inside Pennsylvania.

Virginia abolished Yohogania County in 1786. The small portion of the county that lay outside of Pennsylvania was incorporated into Ohio County, Virginia. Yohogania County's court records, particularly the land deeds, were transferred to Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.23

one of the first maps issued after the end of the American Revolution finessed the western boundaries of Virginia and Pennsylvania by omitting them completely

Source: Library of Congress, The United States according to the definitive treaty of peace signed at Paris Sept. 3d. 1783 (William McMurray, 1784)

Virginia boundaries after abolishing Yohogania County

Source: Michael F. Doran, Atlas Of Boundary Changes In VA 1634-1895

A permanent Virginia-Pennsylvania survey was finalized in 1784-86. It defined the line north from Pennsylvania's southwestern corner, which had been drawn initially by Alexander McClean of Pennsylvania and Joseph Neville in 1782, to the Ohio River.

That Pennsylvania-Virginia border lasted until 1863. When the western counties of Virginia became the separate state of West Virginia, the Virginia-Pennsylvania boundary disappeared and was replaced by the West Virginia-Pennsylvania boundary.

the current Pennsylvania-West Virginia-Maryland boundary is a straight line that was adopted only after a twisting path of many disputes in the 1700's

Source: ESRI,

ArcGIS Online

By the time the western edge of Pennsylvania, "five degrees in longitude... from the said Easterne Bounds" was finally surveyed, the Continental Congress had passed the Land Ordinance of 1785. It outlined how the lands across the Ohio would be surveyed and sold to settlers in an orderly process; rectangular boundary surveys would be completed before the government's land would be sold.

The confusion created by the overlapping claims of Pennsylvania and Virginia was just one of many demonstrations that a new approach to settlement was required. The traditional approach triggered excessive legal disputes.

The "survey before sale" approach and the creation of the Public Land Survey System by the national government replaced the traditional metes-and-bounds surveys done in the past, after settlers selected the best lands and excluded undesired segments of land. The initial surveys of township, range, and section boundaries started in the territory that had been disputed by Pennsylvania and Virginia.

Fort Pitt was clearly within the boundaries of Pennsylvania - at least according to Pennsylvania officials

Source: Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, A map of Pennsylvania exhibiting not only the improved parts of that Province, but also its extensive frontiers (1775)

the Virginia-Pennsylvania border was based on straight lines surveyed across the countryside, not on natural boundaries

Source: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, State of Virginia (by Mathew Carey and Samuel Lewis, 1795)

Pennsylvania ended up with Pittsburgh and Washington County

Source: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, State of Pennsylvania (by Samuel Lewis, 1796)