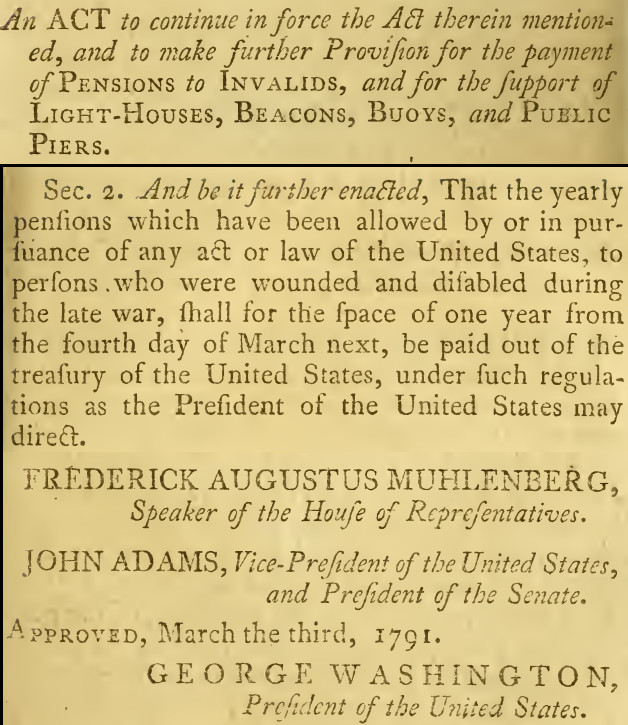

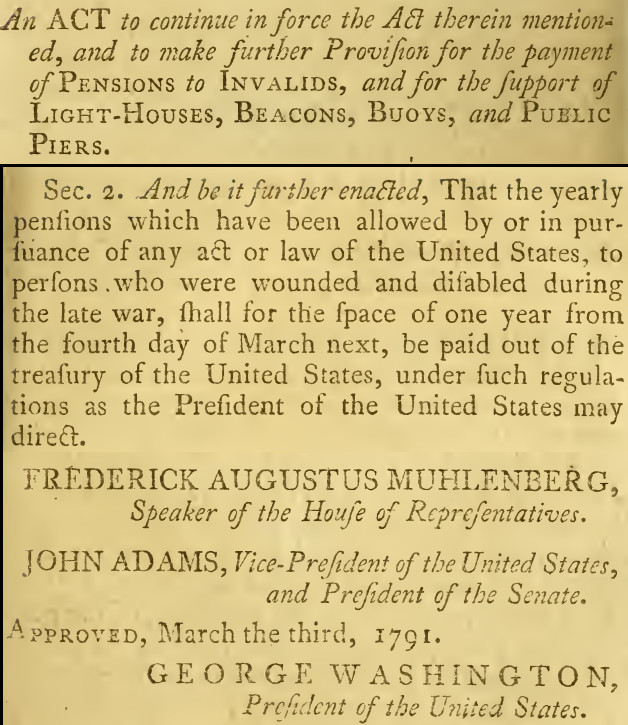

in 1791 the US Congress renewed its commitment to pay the costs of pensions for wounded/disabled Continental Army veterans

Source: US Congress, Acts passed at the third session of the Congress of the United States of America (p.68)

Both the states and the Continental Congress encouraged enlistment and retention in the army and navy during the Revolutionary War by offering pensions in exchange for military service.

The Continental Congress passed legislation on August 26, 1776 granting a lifetime pension to soldiers and sailors who were disabled by military action while serving in the Continental Army. Sailors on armed vessels, plus the marines, also qualified. A disability was considered to be an impairment that prevented a person from engaging in standard unskilled manual labor, such as the loss of an arm or leg.

The monthly pension payment for disabled soldiers was set at one-half of their monthly pay, which varied depending upon rank. Officers were scheduled to receive a higher monthly pay ($26/month for a captain of an infantry company) than standard soldiers ($5/month), so pensions for disabled officers were higher.

Several weeks later on September 16, 1776, the Continental Congress agreed to provide land grants as an incentive. The same distinction based on rank applied to land grants. Colonels were promised 500 acres, lower officers were entitled to less acreage, and the enlisted men and non-commissioned officers were promised 100 acres. the 80,000-90,000 common soldiers who served under George Washington in the Continental Army received warrants for less acreage of western lands.1

The Revolutionary War pensions and land grants mimicked the approach taken by the Virginia General Assembly to recruit soldiers to serve in the French and Indian War. In 1755 the House of Burgesses passed a bill to compensate those wounded at Fort Necessity in 1754. George Washington had been defeated and surrendered to a French force from Fort Duquesne, which was retaliating for his earlier assault on a detachment of French troops and the murder of Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville.

Caring for the wounded was necessary to get soldiers to take risks and fight with bravery. George Wahington wrote in 1757:2

On May 15, 1778, George Washington got assistance from the Continental Congress to keep officers from resigning. Officers who chose to stay in the Continental Army for the rest of the war were promised a pension of half of their pay for seven years after the war ended. Enlisted men who stayed were promised a one-time payment of $80. Foreign officers who volunteered to serve in the Continental Army, such as the Marquis de Lafayette, were not eligible for a pension.

On August 24, 1780, when the British Army had captured Charleston and was rampaging through the Carolinas, the Continental Congress sweetened the offer and promised half-pay for seven years to officers who remained in the army, and to widows and orphans of soldiers who died while in service. A few months later, the pension commitment was extended from seven years to the lifetime of the recipient.3

On April 23, 1782, the Continental Congress decided that privates and non-commissioned officers who were disabled by disease or wounds should get a pension of $5 per month. Death by disease did not qualify for a pension, and widows of enlisted men did not get a pension.4

In 1783, most of the Continental Army was stationed at Newburgh outside of New York City. The officers anticipated being discharged when a peace agreement was finally announced. They were frustrated that they had not been paid their salaries for a long time, and feared their post-war pensions would also not be paid. In the Newburgh, officers planned to march on Philadelphia and demand action by the Continental Congress.

George Washington, a consummate actor, quelled the mutiny when he delivered his Newburgh Address. He included a dramatic gesture at the end, putting on glasses and saying:5

In response to Washington's letters, the Continental Congress then revised the pension plan. Instead of promising half pay for life, it committed to pay officers their full salaries for five years after discharge at the end of the war.6

Because the national government lacked cash, the states had to verify the claims for pensions and pay them until the Federal government was created after ratification of the US Constitution. In 1785, the Continental Congress decided that payments should based on the extent of a disability, and claimants had to testify annually in a local court regarding their disability.

On September 29, 1789, President Washington concurred with pension legislation passed by the new US Congress. The Federal government agreed to pay for a year the pensions of wounded/disabled officers (half pay) and soldiers ($5/month). That commitment was then extended by further laws, as the national government gained the capacity to raise revenue (primarily from tariffs) and pay what it had promised. Starting in 1792, new pension requests had to be filed with the national government. That reduced the workload imposed on the states to adjudicate applications.

in 1791 the US Congress renewed its commitment to pay the costs of pensions for wounded/disabled Continental Army veterans

Source: US Congress, Acts passed at the third session of the Congress of the United States of America (p.68)

In 1792, the Federal government was paying $5/month pensions to 1,358 non-commissioned officers and privates. Eligibility was expanded in 1806; disabled veterans who had served in state units as well as the Continental Army were able to receive Federal pension. Veterans who had become disabled after the war ended also qualified for pensions. In 1816, pension payments were increased to $8/month. At the time:7

The War of 1812 created a new sense of national pride and on March 18, 1818, the US Congress broadened the qualifications for a Revolutionary War pension. Qualification were relaxed to permit pensions for those who were in poverty and who had served in the navy or Continental Army for at least 9 months, or until the end of the war. For the first time, a soldier who was not disabled was entitled to a pension.

The 1818 law was intended to support soldiers who were poor. Many applicants for pensions manufactured specious reports of their economic condition.

To cope with the surge of applications and questionable claims of poverty, a new law in 1820 required veterans to submit proof of their financial status. Some veterans transferred their assets to their children in order to appear poor. By 1823, nearly 6,500 veterans had failed to prove their low economic status and lost their pensions but over 12,000 veterans were still on the rolls. Those who lost their pensions were allowed to appeal, but had to prove they had not shuffled their assets to disguise their actual wealth. Altogether, 20,485 men received pensions based on the 1818 law.

The requirement to be disabled or in poverty to receive a pension was removed in 1828; that added 1,200 men to the rolls. The minimum criterion for a Federal pension equal to full pay became the threshold established in 1778. If a person had served until the conclusion of the war, they qualified. However, the full pensions were capped at a captain's pay.

Another change in 1832 granted full pay pensions to veterans who had served at least two years during the American Revolution, including being an enlisted man or officer in state forces. A reduced amount was granted to those who served at least six months, which covered those who served in most state militia units. The 1832 change added 33,425 pensioners. By 1834, there were 43,000 claimants who qualified under one of the various acts.

Virginia received a special benefit under a law passed by the US Congress on July 5, 1832. The Federal government assumed pension responsibility for those who had served in the Virginia Navy, and for some of the officers in state forces who were receiving half pay.

Widows were authorized to receive pensions (as opposed to disability payments) in 1836, if the marriage to the veteran had occurred while he was serving in the military during the American Revolution. The criteria were loosened in several acts. In 1838, widows were allowed to get a pension for five years if they had married the veteran before the start of 1794.

An 1848 law extended benefits to widows were married to veterans by at least January 1, 1800. In 1853, the date of the marriage was eliminated as a qualification. By that time, there were few remaining widows.

By 1867, all of the 57,623 veterans who had received a pension under one of the Federal laws had died. By then, the Federal government paid $46,178,000 to Revolutionary War veterans and family members who qualified for pensions.

About 900 widows were still receiving benefits in 1869. The last legislation by the US Congress regarding Revolutionary War pension was a law passed in 1878. The few remaining widows were granted a pension if they had married a veteran who had served a minimum of 14 days or who had fought in any battle.8

Grants of western land were also promised by the national and state governments for service in the Revolutionary War. Those land grants matched an incentive used by Virginia's colonial officials to recruit soldiers to serve in the French and Indian War in 1754 and in Dunmore's War in 1774.