Virginia Military District - Kentucky

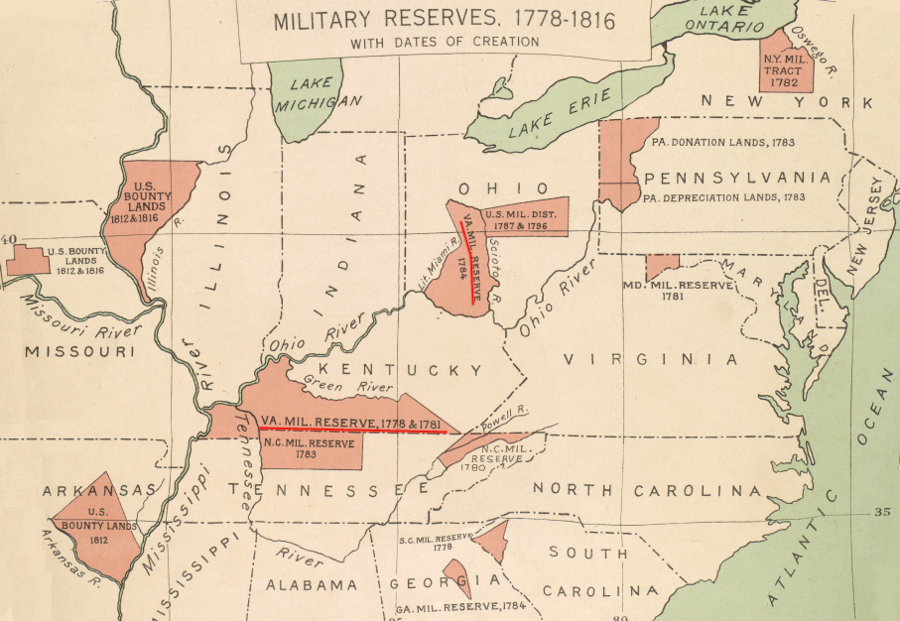

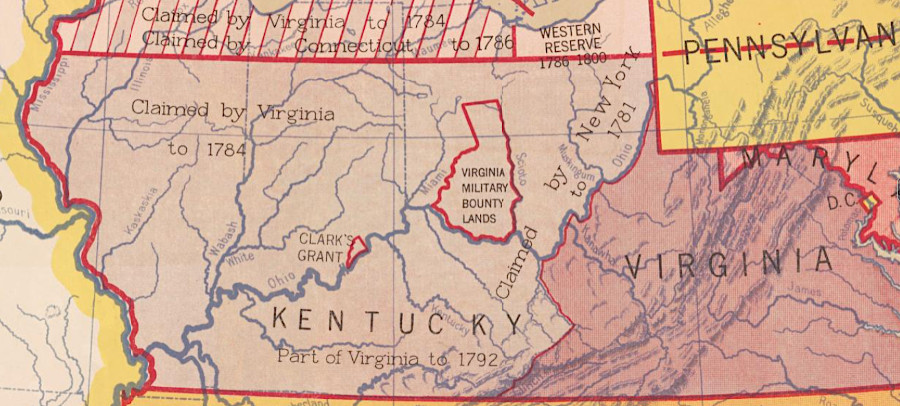

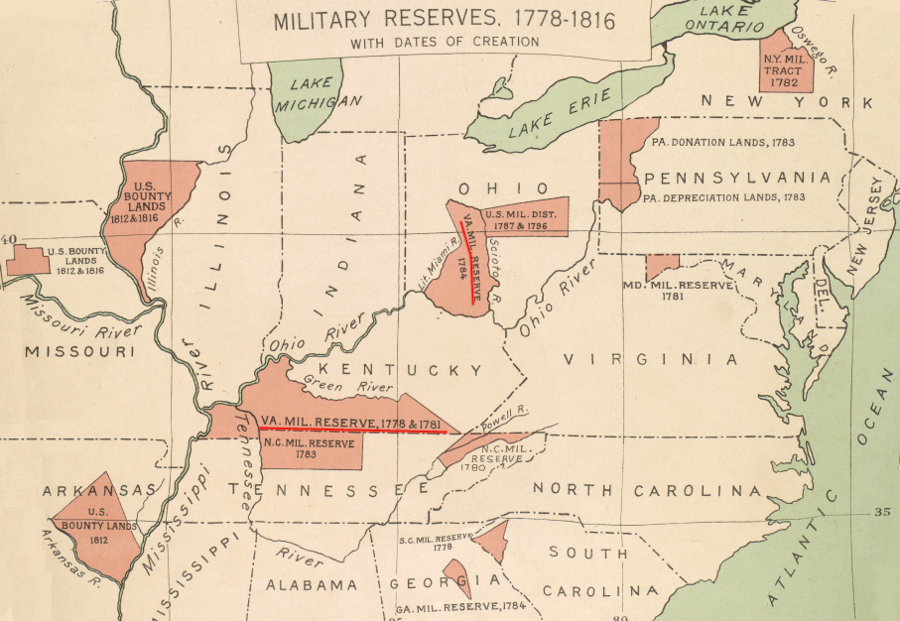

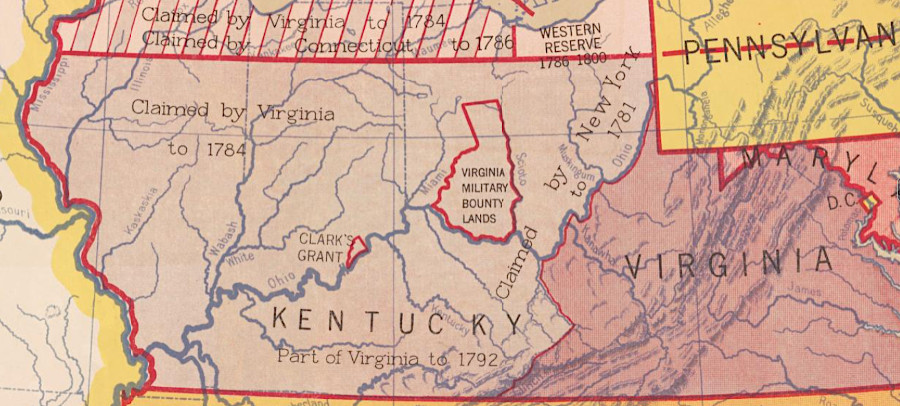

Virginia Revolutionary War veterans could claim land in two military districts, one on each side of the Ohio River in the modern states of Kentucky and Ohio

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Military Reserves, 1778-1816, With Dates of Creation (Plate 45b, digitized by University of Richmond)

Virginia's General Assembly enticed men to join the First Virginia Regiment in the French and Indian War by offering free land. A similar offer of "bounty land" was used to recruit soldiers to serve in the Continental Army and Virginia Navy during the American Revolution.

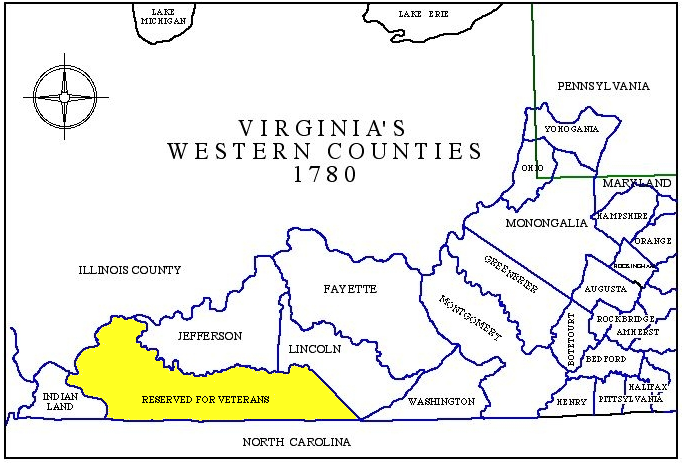

The state met its commitment to provide land by establishing two special military districts that together totaled 5.7 million acres. The land within those two districts was reserved for disposal to just veterans. The two districts were located on the western edge of Virginia, in areas not yet occupied by settlers.

In 1753 when Governor Dinwiddie learned that the French were building forts on Lake Erie and on the Ohio River, he sent George Washington to notify the French commander at Fort LeBoeuf that the Virginia government viewed them as trespassers. Virginia claimed the land in the Ohio River Valley based on the Third Charter issued by King James I in 1612.

Washington was rebuffed; the French claimed the same land based on the Right of Discovery. René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle had led an expedition that paddled down the Mississippi River. On April 9, 1682, he had erected a cross at the mouth of the Mississippi River and claimed the entire watershed in the name of King Louis XIV.

After Washington reported back that diplomacy had failed, Governor Dinwiddie obtained authorization from the Governor's Council to prepare a military response. Governor Dinwiddie appointed Joshua Fry as Colonel and George Washington as Lieutenant Colonel of a special militia expedition intended to force the French to acknowledge the primacy of Virginia's claim. The Ohio Company sent 100 men to build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio (now modern-day Pittsburgh).

Fry died and Washington took charge. He found recruiting militia from the western counties was difficult. According to colonial law, every white male between the ages of 18-60 was automatically in the militia and responsible for having a musket or rifle. There were supposed to be 10 companies in each county who assembled for monthly militia training, but the County Lieutenants in the sparsely-settled region had not created and trained well-organized forces. Starting farms in the area required all the time available. Individual families prepared to defend their homes against Native American raids rather than trained with others to create an effective local militia unit.

County Lieutenants had the power to draft men of military age to serve. They were already by default in the militia, so technically they never "enlisted" to fight. County Lieutenants were local leaders, however, and were at risk of losing local support if they forced people to leave their farms and serve in an unpaid militia job.

Since few men were willing to volunteer for Lord Dinwiddie's special militia assignment, some county officials proposed releasing men from the local jail to serve under Fry and Washington. Washington expressed his frustration with his recruitment efforts in a letter to his brother, saying:1

- ...you may, with almost equal success, attempt to raize the Dead to Life again, as the force of this Country.

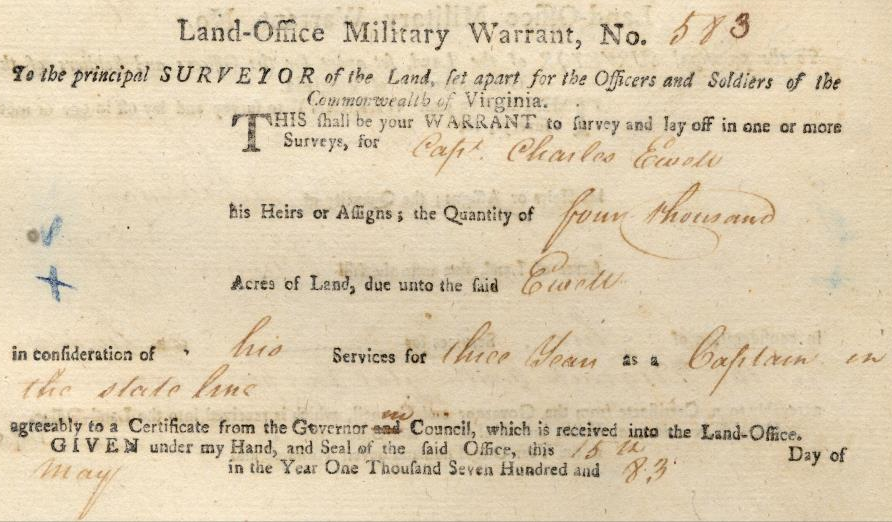

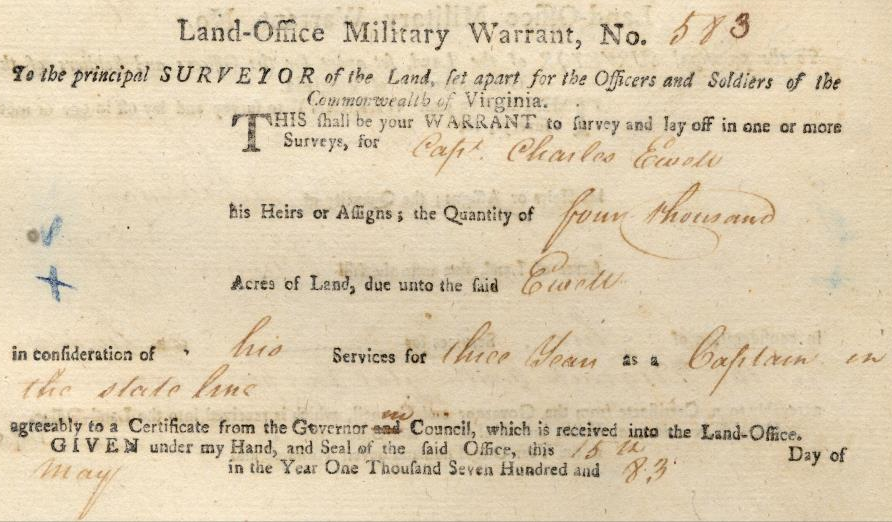

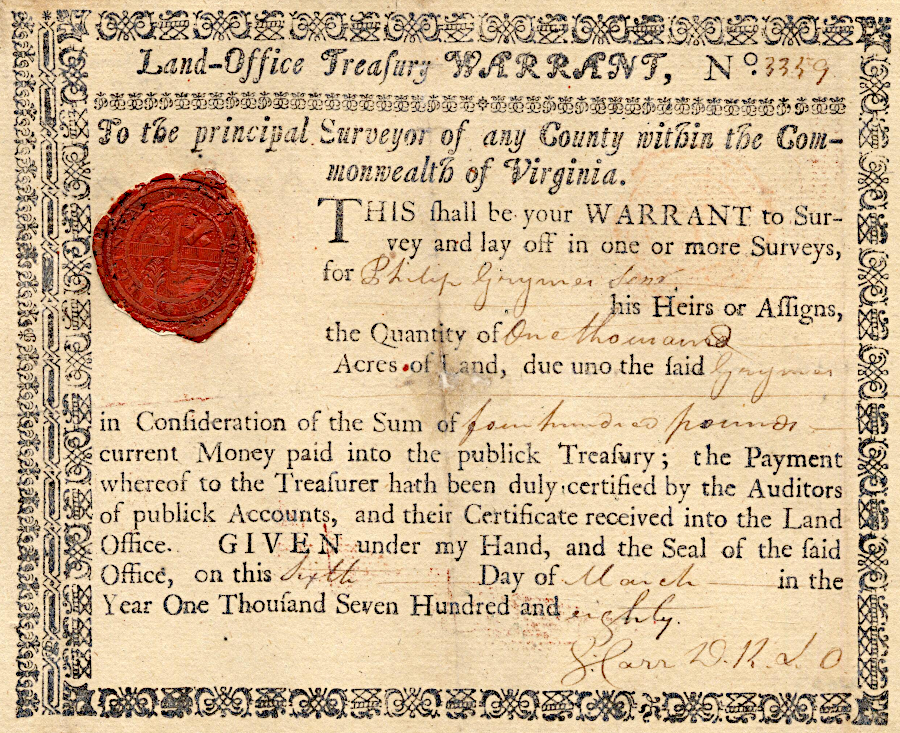

To claim the bounty lands to which French and Indian War veterans were entitled required getting a warrant, a piece of paper from the Secretary of the colony in Williamsburg. Common soldiers were entitled to less acreage than than officers, and the acreage was specified in the warrant. The warrant was presented to the county court, which then authorized a surveyor to define a parcel equal in size to the acreage in the warrant. The surveyor's drawing was presented to the Secretary of the colony, who then issued a patent (also known as a grant) that served as the legal deed to the property.

Before the American Revolution, no specific area was set aside to guarantee enough land would be available to meet the total acreage for all soldiers who served. The Proclamation of 1763, issued at the end of the French and Indian War, was a barrier to settlement of the western lands.

the statue to the First Virginia Regiment in Richmond was removed, along with all Confederate monuments on city land, in 2020

Source: Wikipedia, Virginia Regiment

Recruiting soldiers to fight in the American Revolution was also difficult. However, the Proclamation of 1763 was no longer an impediment to the newly-independent Commonwealth of Virginia,

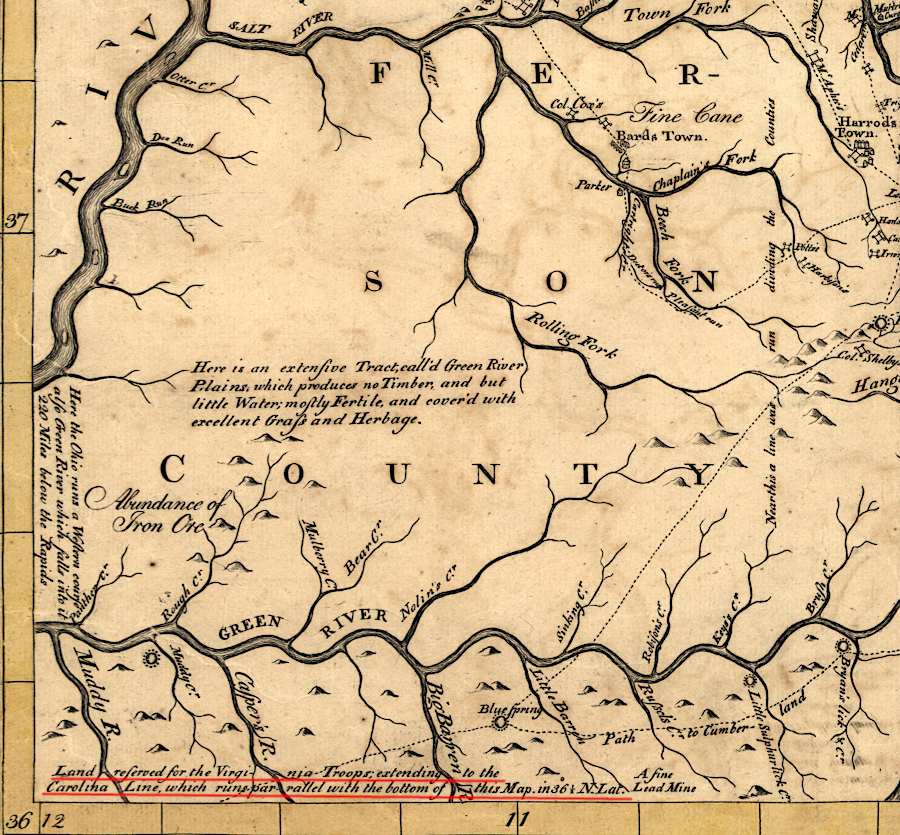

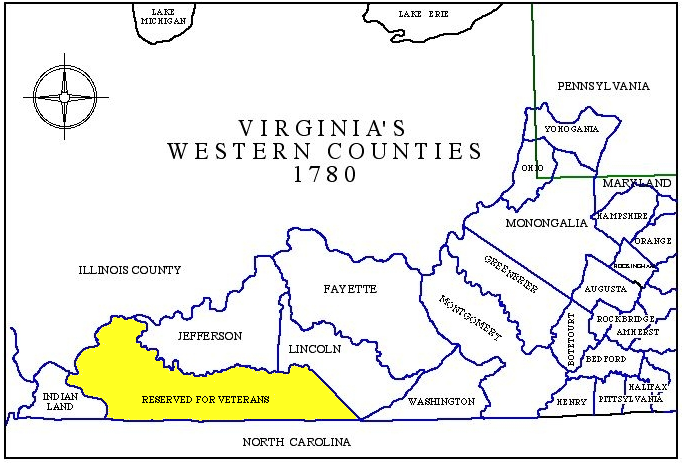

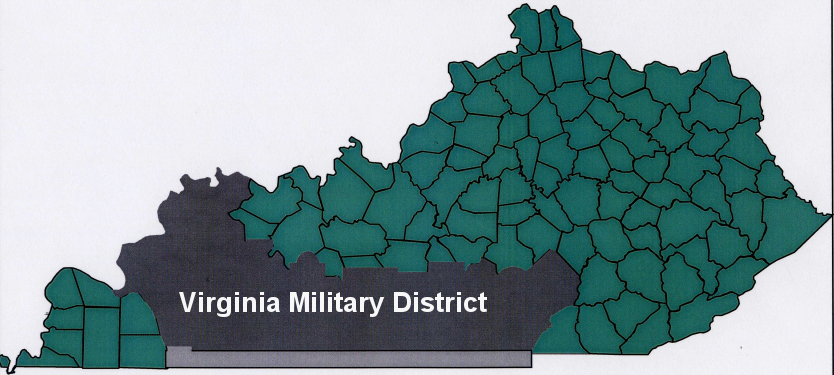

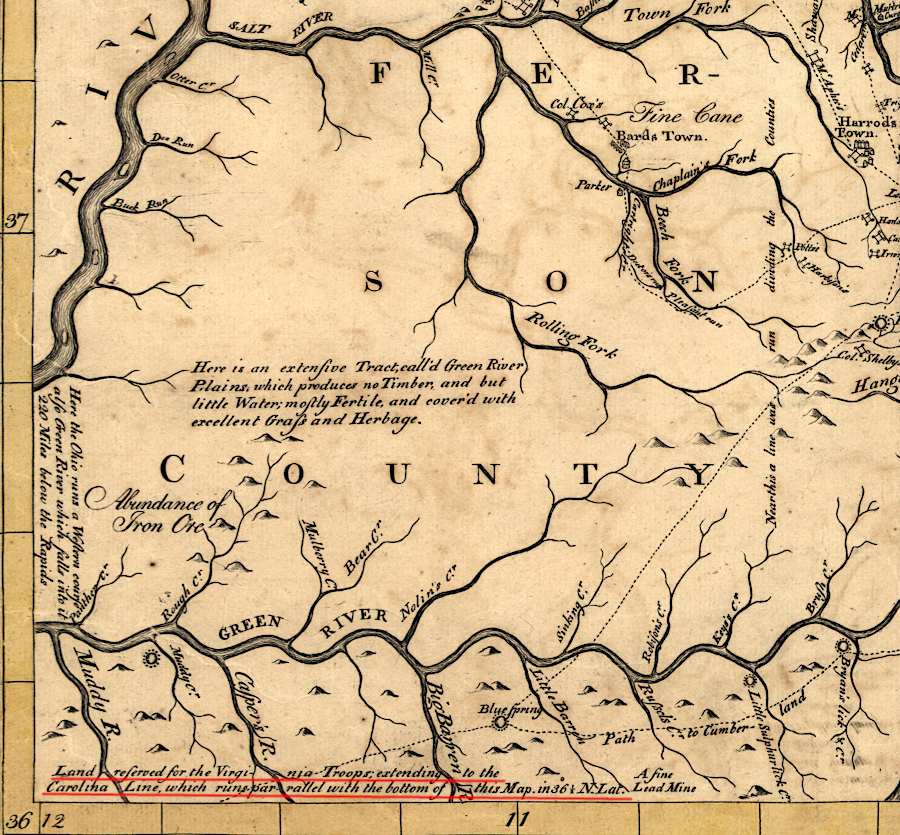

In the Virginia Land Law of May 3, 1779, the General Assembly officially reserved lands between the Green River and the North Carolina boundary in what later became the state of Kentucky. Practically, the eastern border of the Virginia Military District was at the "Cherokee or Tennessee river" rather than the Cumberland Mountain (now the eastern border of Tennessee) because settling was not authorized within territory still claimed by the Cherokee.

Soldiers granted a bounty of land to enlist in the state forces or the Continental Army could select any parcel of vacant land state-owned land. Until January 1, 1778, so could others with treasury rights. Under the 1779 land law, treasury rights were no longer valid in the reserved district if dated after January 1, 1778; only soldiers with a military warrant could select a parcel there.

The rights of Richard Henderson were respected in the 1779 law; a military warrant could not be used on parcels he had already identified. The General Assembly chose to negotiate with Henderson rather than simply reject all of the patents he awarded, which were based on his purchase from the Cherokee in the 1775 Treaty of Sycamore Shoals. Preemption claims establish by settlers who had planted corn or lived on the parcel were also protected. Preemption claims were limited to 400 acres, but an additional 100 acres could be purchased.

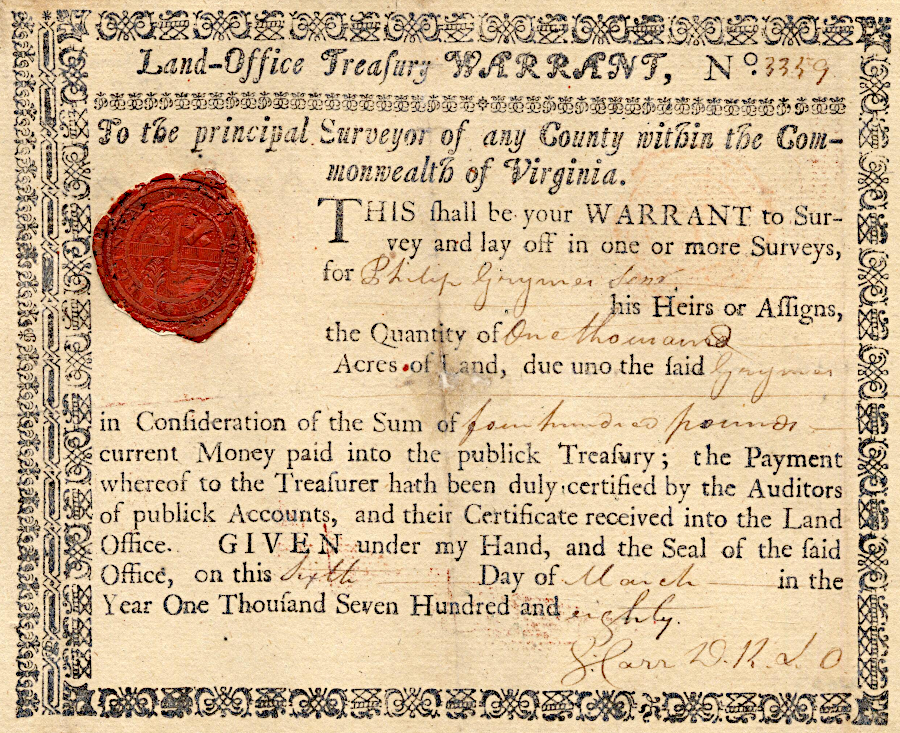

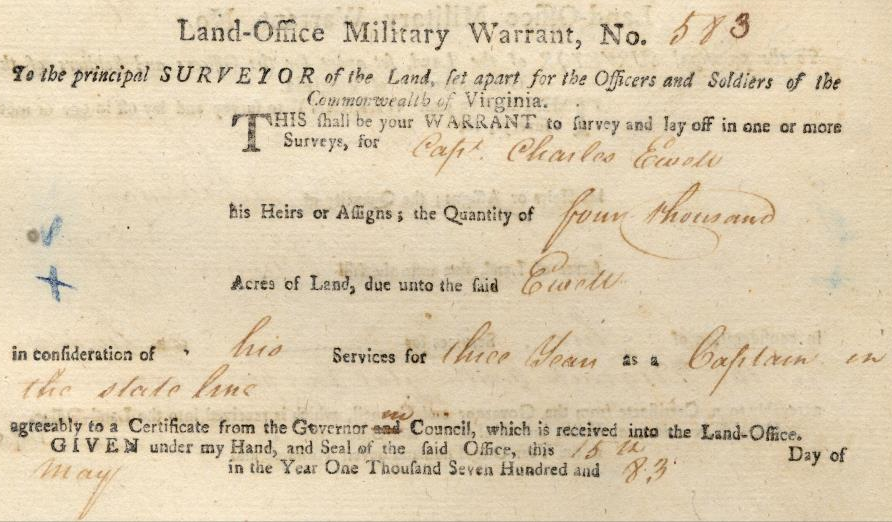

Land grants were a standard incentive to recruit soldiers to serve beyond routine militia duties until the Civil War. The General Assembly promised land to soldiers in the American Revolution if they were willing to serve at least three years continuously in the State or Continental Line, or as a sailor in the Virginia Navy.

the number of acres of bounty land awarded for Revolutionary War service was determined by the soldier's rank and time of service

Source: Kentucky Secretary of State, Grymes, George (Revolutionary War Warrant 1589.0)

Since Tennessee had not been established as a separate state at the time, the southern boundary of the 1779 reservation was defined using the "Carolina line":2

- ...a certain tract of country to be bounded by the Green river and a southeast course from the head thereof to the Cumberland mountains, with the said mountains to the Carolina line, with the Carolina line to the Cherokee or Tennessee river, with the said river to the Ohio river, and with the Ohio river to the said Green river, ought to be reserved for supplying the officers and soldiers in the Virginia line with the respective proportions of land which have been or may be assigned to them by the general assembly, saving and reserving the land granted to Richard Henderson and company, and their legal rights to such persons as have heretofore actually located lands and settled thereon within the grounds aforesaid.

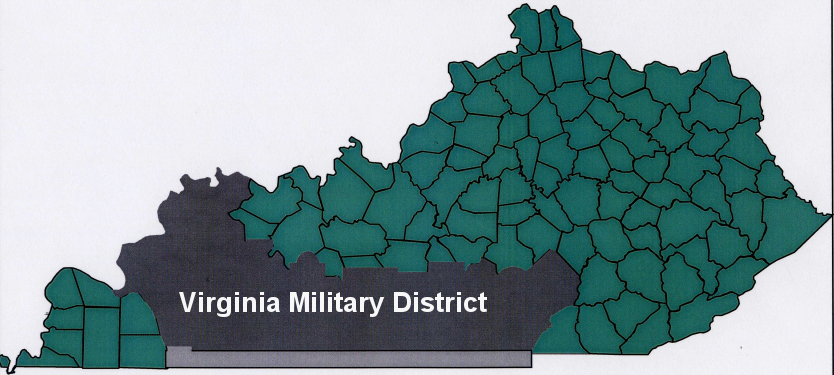

the Virginia Land Law of 1779 created a military district in Kentucky

Source: Kentucky Secretary of State, Virginia's Military District in Kentucky

North Carolina later defined its own military district in its western lands before ceding what became Tennessee to the Continental Congress.3

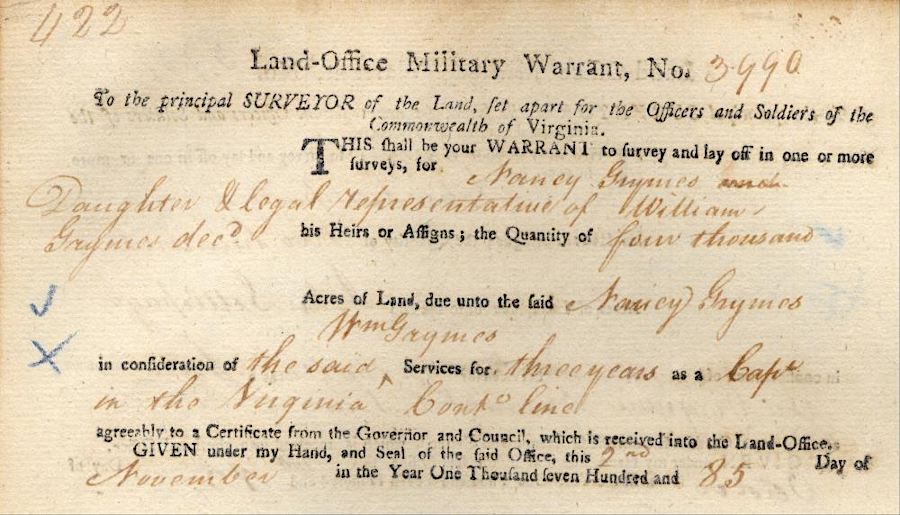

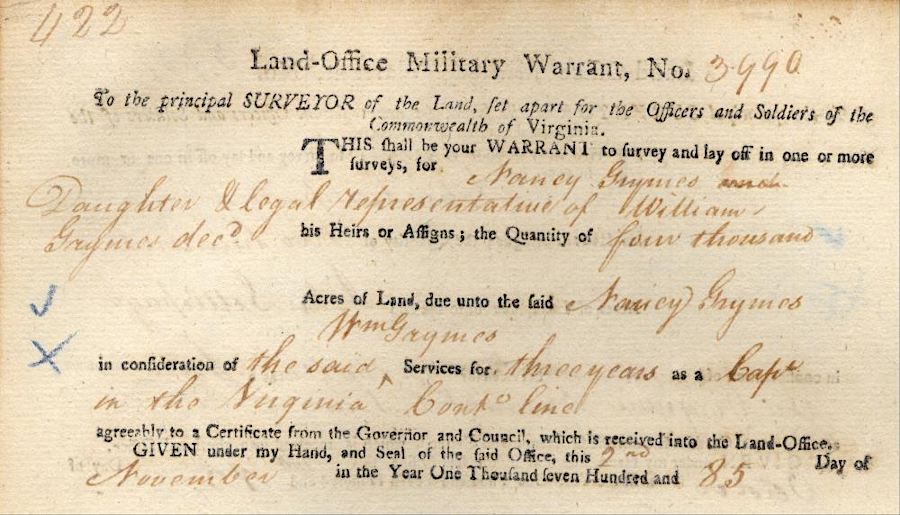

The Governor and his staff reviewed requests from soldiers, sailors, heirs, and those who purchased their rights for land based on military service. Applicants whose claims were judged to be qualified were given a military certificate.

That document was taken to the Land Office created in 1779, which would issue a warrant. Land warrants were presented by the claimant to the county surveyor, who would provide the boundary survey for the amount of acreage listed on the warrant. Claimants then filed the survey with the county court, and it issued a patent. Land patents start the chain of title which documents land transfers over time to modern owners.

Proof of military service was needed:4

- Servicemen submitted various documents such as affidavits of commanding officers and fellow soldiers and discharge papers in order to substantiate their service record... When a claim was proved, the Governor's Office issued a military certificate to the register of the Land Office (see Land Office Military Certificates) authorizing him to issue a warrant specifying the amount of land to be received and directing the land to be surveyed. The amount of land awarded was based on the rank of the soldier and the amount of time served.

an official land warrant authorized surveyors to identify land in the Virginia Military District for veterans of the French and Indian War

Source: Kentucky Secretary of State, Virginia and Old Kentucky Patent Series

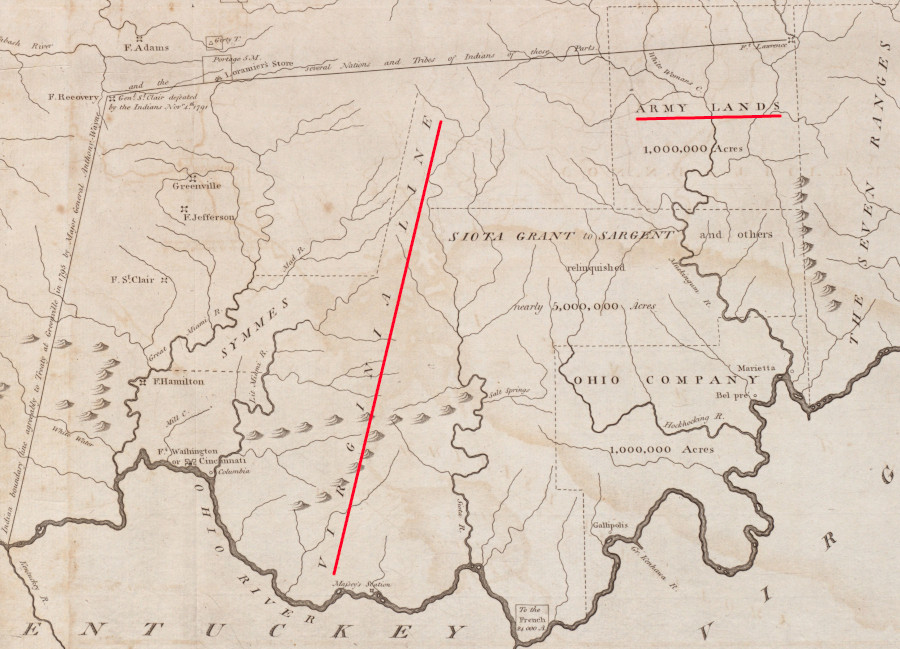

the military district in Kentucky was south of the Green River

Source: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, The Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke (John Filson, 1784)

Virginia created a military district in 1779, before Kentucky became an independent state in 1792

Source: Kentucky Secretary of State, Virginia's Western Counties 1780

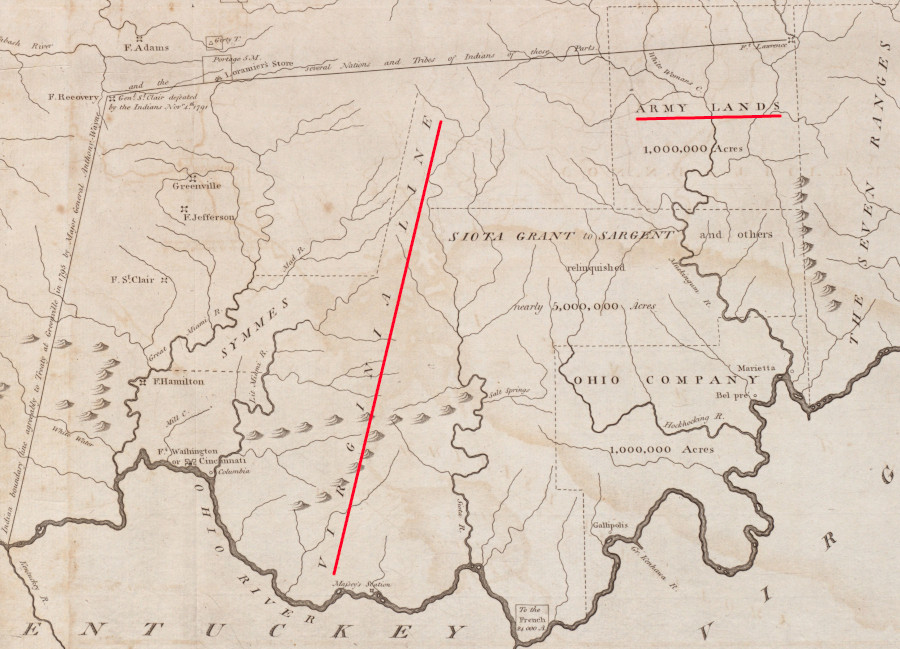

Claiming land grants during the American Revolution was unrealistic, but soon after the Treaty of Paris the state began to honor its promise. Virginia opened a land office at Soldier's Rest near Louisville on July 20, 1784, to complete the metes-and-bounds surveys required to define the boundaries of specific parcels.

Robert C. Anderson was the principal surveyor appointed by Virginia to run the land office. Within three years he recognized that there was insufficient land remaining in the military reservation in Kentucky. He opened for survey the Virginia Military Reservation in Ohio on August 1, 1787, soon after the Continental Congress passed the Northwest Land Ordinance on July 13.

The US Congress disagreed and voided the initial surveys, after deciding there was still land to be granted in Virginia's Cumberland Reservation in Kentucky. Processing to eventually award patents (land deeds) for military service was limited to surveys in Kentucky until 1790, when the US Congress authorized surveying land north of the Ohio River.5

When Kentucky became a separate state in 1792, it agreed to honor the Virginia warrants for authorizing future surveys. Kentucky opened the lands south of the Green River to non-veteran settlers who met the state's age and residency requirements, but had no military warrant.

On December 21, 1795, Kentucky's General Assembly passed an act which required the claimant for land in the state's military district to file paperwork before January 1796 to start the process. After that date, land in the Virginia Military District which had not been not identified for a military claim could be patented by others. To define the specific boundary of the military district, Kentucky surveyed a line "from the head of Green river to the Cumberland mountain" in 1798.

Some people holding warrants for military land claims, including heirs of veterans and speculators who had purchased the warrants at a discount, filed required paperwork in the Kentucky land office but did not survey specific parcels and obtain final patents. Some claims could not be processed because they conflicted with lands reserved for a settlement with the Transylvania Company. Those who had filed warrants were entitled to land, but finding available parcels was not always feasible. Latecomers discovered that other settlers had already established rights to almost all the land in the district between the Green River and the Tennessee border.

Captain Charles Ewell of Prince William County obtained a warrant in 1783 for a surveyor to define his 4,000-acre parcel of bounty land in Kentucky

Source: Kentucky Secretary of State, Revolutionary War Warrant 0583.0

In 1818, Kentucky purchased claims to land west of the Tennessee River, where some Revolutionary War veterans had already settled. The Jackson Purchase was acquired from the Chickasaw. The Kentucky General Assembly passed a law in 1820 requiring all holding military warrants to complete surveys and file for patents in the Jackson Purchase by the start of 1823. That led to the grant of 242 more patents.6

Heirs and others holding rights to Revolutionary War military land claims obtained the first Bounty Warrants in 1783. A total of 4,748 bounty land warrants were processed. The last grant was awarded in 1876.7

descendants of soldiers and officers, or of land speculators who purchased rights to file claims, obtained bounty lands until 1876

Source: Kentucky Secretary of State, Detailed Information About Grymes, William (deceased) (Land Warrant 3990.0)

Clark's Grant, 150,000 acres rewarded to members of the members of George Rogers Clark's expedition that captured Vincennes in 1779, ended up in the state of Indiana

Source: Library of Congress, State claims, 1776-1802 (Hart-Bolton American history maps, 1917)

Links

two districts with lands for military veterans were established in the Land Ordinance of 1785

Source: Leventhal Map Collection, Boston Public Library, A map of part of the N:W: Territory of the United States: compiled from actual surveys, and the best information (by Samuel Lewis, 1800)

References

1. "Cavelier De La Salle, Rene-Robert," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cavelier_de_la_salle_rene_robert_1E.html; "Washington and the French & Indian War," Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/french-indian-war/washington-and-the-french-indian-war (last checked June 10, 2025)

2. "Revolutionary War Military District," Kentucky Secretary of State, http://www.sos.ky.gov/admin/land/military/revwar/Pages/Revolutionary-War-Military-District.aspx; "Location of Military District - December 19, 1778," Kentucky Secretary of State, https://www.sos.ky.gov/land/resources/legislation/Documents/Location%20of%20Military%20District.pdf (last checked July 10, 2025)

3. "Early North Carolina / Tennessee Land Grants at the Tennessee State Library and Archives," Tennessee Secretary of State, https://sos.tn.gov/tsla/guides/early-north-carolina-tennessee-land-grants-at-the-tennessee-state-library-and-archives (last checked June 15, 2025)

4. "Clark's Daring Plan," Indiana Historical Bureau, https://secure.in.gov/history/2993.htm; "Revolutionary War Military District," Kentucky Secretary of State, http://www.sos.ky.gov/admin/land/military/revwar/Pages/Revolutionary-War-Military-District.aspx; "About the Revolutionary War Bounty Warrants," Library of Virginia, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/opac/bountyabout.htm; "Colonial Wars Bounty Lands (VA-NOTES)," Library of Virginia, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/va16_colonial.htm (last checked January 17, 2021)

5. Nelson Wiley Evans, A history of Adams County, Ohio, 1900, pp.39-40, https://archive.org/details/ahistoryadamsco01stivgoog; "Northwest Ordinance (1787)," National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/northwest-ordinance (last checked July 5, 2025)

6. "Revolutionary War Military District," Kentucky Secretary of State, http://www.sos.ky.gov/admin/land/military/revwar/Pages/Revolutionary-War-Military-District.aspx; Dr. George W. Knepper, Ohio Lands Book, The Auditor of State (Ohio), 2002, pp.19-23, https://ohioauditor.gov/publications/OhioLandsBook.pdf; "Atlas of Historical County Boundaries," Newberry Library, https://publications.newberry.org/ahcbp/map/map.html#VA; "Anderson, Richard Clough. Papers, Ohio Manuscripts, 1782-1905, 1912-1914," University of Illinois Library, https://archon.library.illinois.edu/ihlc/index.php?p=collections/controlcard&id=425; "Payment to Croghan & Thompson 1798," Kentucky Secretary of State, https://www.sos.ky.gov/land/resources/legislation/Documents/Payment%20to%20Croghan%20Thompson.pdf (last checked July 10, 2025)

7. "Revolutionary War Warrants Database," Kentucky Secretary of State, https://sos.ky.gov/admin/land/military/revwar/Pages/default.aspx; "About the Revolutionary War Bounty Warrants," Library of Virginia, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/opac/bountyabout.htm (last checked January 23, 2021)

The Military in Virginia

Virginia Places