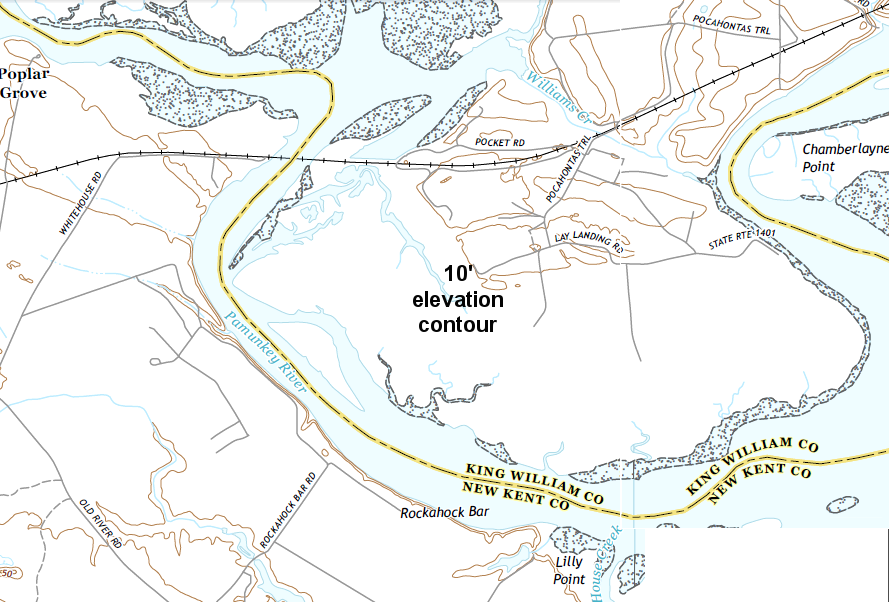

the low elevation of the Pamunkey Reservation makes it vulnerable to sea level rise

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tunstall and New Kent 1:24,000 scale quadrangle maps

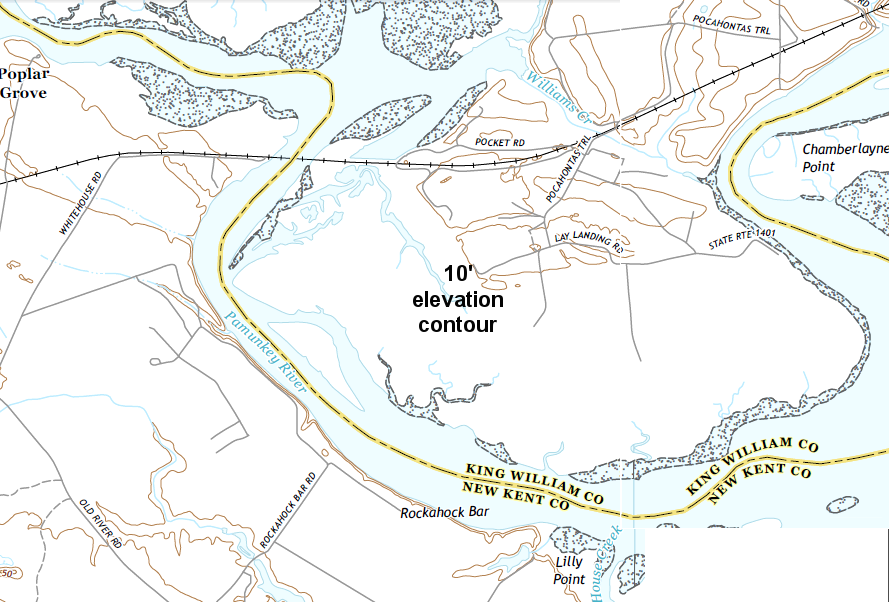

the low elevation of the Pamunkey Reservation makes it vulnerable to sea level rise

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tunstall and New Kent 1:24,000 scale quadrangle maps

The Pamunkey were forced to surrender control of nearly all of Tsenacomoco after a failed uprising in 1644. The tribe has managed to maintain a remnant of their territory on Pamunkey Neck for four centuries.

The potential to retain that control for another four centuries will be affected by climate change.

Topographic maps reveal that the highest point on the reservation is about 10 feet above sea level. The tribe is building a living shoreline on the edge of the river to reduce erosion due to river currents and boat wakes, but that rock barrier will not mitigate all the impacts of sea level rise. The "neck" of Pamunkey Neck could be underwater in 50 or so years.1

During the lifetime of current Pamunkey children, strong storms could flood the tribal museum, old schoolhouse, and houses of those living on the reservation.

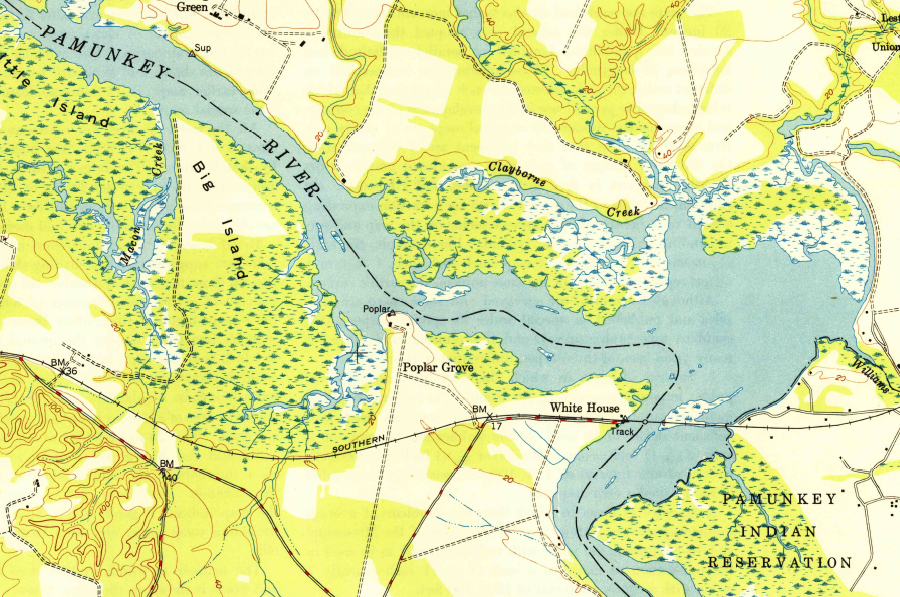

If the reservation is flooded by rising sea levels, much of the Virginia coastline will go underwater with it. That includes the nearby Mattaponi reservation, Werowocomoco (the home of Powhatan when the English arrived in 1607), and the island where Jamestown was settled by English colonists. Swamps upstream will be transformed into open water.

rising sea levels will convert wetlands into open water, as well as inundate dry land

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tunstall 1:24,000 scale topographic quadrangle (1949)

After Superstorm Sandy in 2012, Anne Arundel County in Maryland assessed the threat to archeological sites on the shoreline. It concluded that 80% of the sites which would be lost to rising sea levels were associated with Native American heritage.

The Longwood Institute of Archaeology assessed the vulnerability of archeological sites on 1,237 miles of the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia. It determined that nearly 50% of the shorelines are migrating inland. In addition to Native American sites, 28 out of 313 historic sites were likely to be washed away in the next 50 years.

Over the last 18,000 years of sea level rise, the campsites of the first Virginians have been drowned and are 40 miles east of the modern coastline. Sites with Clovis points from the Paleo-Indian Period, atl-atl bannerstones from the Archaic Period, and bird points from the Woodland Period have disappeared steadily. Sites along the pre-historic Susquehanna River have been covered by the rising waters until the Chesapeake Bay reached its present shape about 3,000 years ago. The Eastern Shore is just a remnant of the Coastal Plain that has been inundated.

Virginia's "threatened sites fund" allows archeologists to salvage a portion of the information from some of the sites that are disappearing. The Pamunkey reservation may qualify soon.2

In 2025, the National Trust for Historic Preservation listed the reservation as one of the top 11 most endangered historic sites, saying:3

by 2040, sea level rise could drown the marshes around the Pamunkey Reservation

Source: Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Flooding Resiliency, Sea Level Rise Projection