when the reservation for the Pamunkey was established in 1646, the marshes were not desired as farmland by the colonists

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

when the reservation for the Pamunkey was established in 1646, the marshes were not desired as farmland by the colonists

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

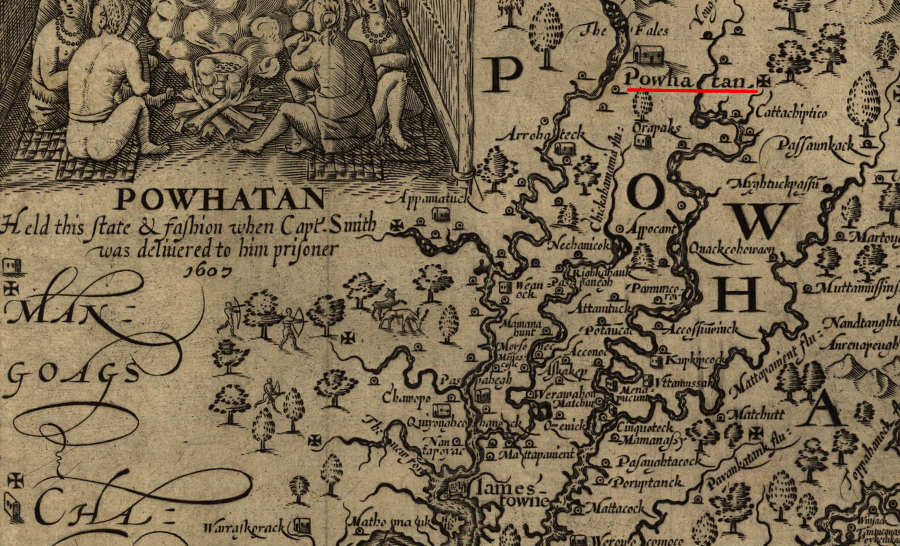

In a 1646 treaty ending the Third Anglo-Powhatan War, Necotowance agreed to vacate the Peninsula between the James and York rivers. Necotowance was the leader of the remnants of Powhatan's paramount chiefdom, replacing Opechancanough after he had been captured and murdered while imprisoned in Jamestown. Gov. William Berkeley signed the treaty for the colonists.

Under the terms of that treaty, the Native Americans were obliged to stay north of the York River. That cut them off from perhaps half of Tsenacomoco, the territory once under control of Powhatan. English colonists were authorized to kill any Native American on the Peninsula who was not wearing a special badge or a striped coat signifying the visit was authorized:1

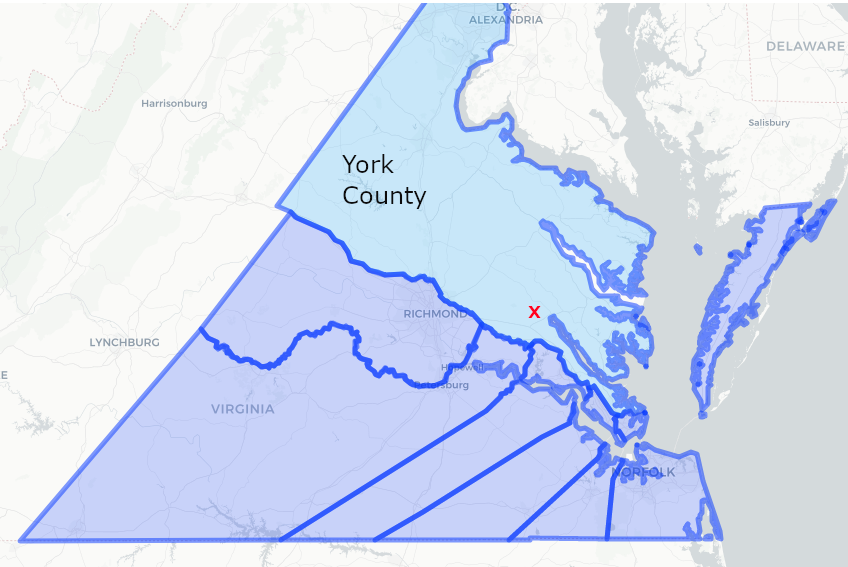

In that treaty, the English agreed that the Native Americans could continue to live north of the York River. Pamunkey Neck was in York County in 1646; today it is within King William County. County boundaries have changed, but that site has always been occupied by the Pamunkey tribe. It is the one location in Virginia where Native Americans can be very specific when saying "We never disappeared; we have always been right here."

in 1646, all the land north of the Pamunkey River was in York County

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

In 1649, the General Assembly granted the Pamunkey leader known to the colonists as Tottopotomoy 5,000 acres of land on the Pamunkey River. While English squatters were expelled from that land in 1653, the grant was not re-confirmed when the legislature revised its laws again in March 1658 (1657 Old Style). Pressure by colonists to claim some of that land may have deterred the General Assembly from re-confirming the grant, but Native Americans continued to use most of the area.2

the presence of Native Americans at the current sites of the Pamunkey amd Mattaponi reservations, and at Powhatan's last capital of Matchut, was documented in 1670

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman, 1670)

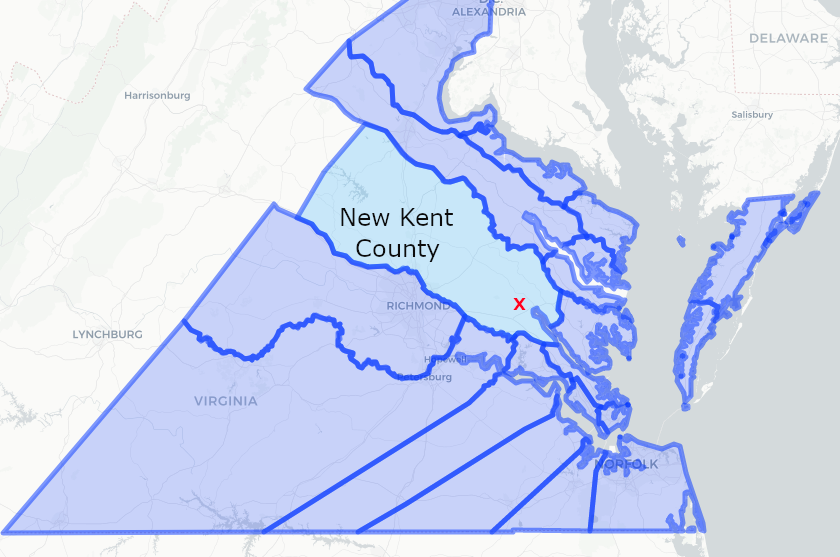

The 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation created an 6-mile wide, 18,000-acre exclusive Native American zone by prohibiting colonists from living within three miles of the settlement on Pamunkey Neck. By that time, the site reserved for the tribe was within the boundaries of New Kent County.

In 1683, a raid by "Seneca" from New York forced the Mattaponi and Chickahominy to move from their settlements on the Mattaponi River, and they moved in with the Pamunkey.

when the original reservation for the Pamunkeys was established in 1677, Pamunkey Neck was in New Kent County

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

When the threat from the Iroquois diminished after several years, those two tribes moved back "home." The Chickahominy ended up south of the York River, outside the area reserved for Native Americans in the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation. The Mattaponi moved north to the Mattaponi River, still within the zone of the treaty lands. As a result, trustees appointed by Virginia to deal with reservation issues stayed involved with Mattaponi as well as Pamunkey tribal members.

In 1693, the colonial government allowed the Pamunkey to sell 5,000 acres of their land. That helped them pay debts and relieved some pressure to extinguish the reservation completely.

Over time, more slices of land were transferred out of Pamunkey control, leaving the tribe with an inadequate land base for subsistence by hunting and gathering. Since 1894, the Pamunkey have controlled 1,200 acres and the Mattaponi 150 acres, in separate reservations. That is 8% of the original 18,000 acres.

badge that a Native American had to wear after 1646 on the Peninsula

Source: National Park Service, A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century

Since the Pamunkey were not citizens of Virginia, the colonial government appointed trustees to represent their interests. After the American Revolution, the Commonwealth of Virginia perpetuated the practice. In 1799, the General Assembly passed a law allowing the Pamunkey to choose those trustees rather than have the state be responsible for selecting them. The trustees were also empowered to establish the laws, rules and regulations for the tribe's governing processes.

Starting in 1836, the Pamunkey were threatened by an effort to terminate their reservation. That would have led to sale of the lands and dispersal of the tribe.

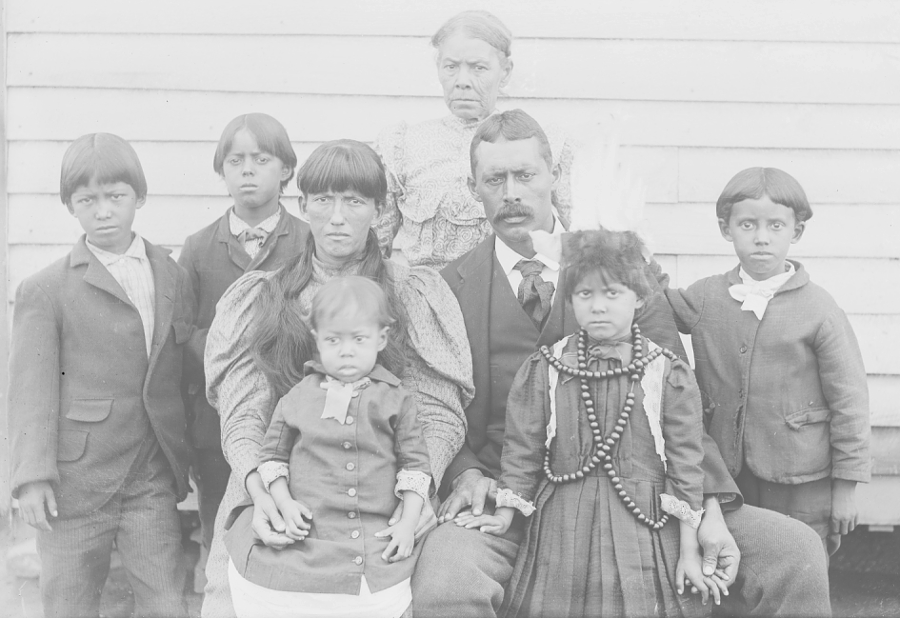

One man led the effort, claiming that the Pamunkey were not sufficiently "Indian" as a result of generations of intermarriage with slaves and free blacks. The effort coincided with efforts to eliminate free blacks in Virginia after Nat Turner's uprising in 1831. The white neighbors living near the Pamunkey Reservation did not support its termination, and the General Assembly rejected the proposal.

The threat galvanized the Pamunkey and strengthened the community's determination to persist. One response led to limits on interactions and marriages with free blacks. Until 2012, Pamunkey law said:3

the Pamunkey have maintained a distinct and separate culture on their reservation since the 1600's

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Family of George Mayor Cook, Group of Eight, Near Wood Frame Building OCT 1899

The claim that the tribe had not intermarried helped the Pamunkey survive the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. The "racial purity" claimed by the Pamunkey helped block state-sponsored initiatives to reclassify every person in the state who had one drop of blood from a non-white ancestor as black, and then to apply Jim Crow discrimination laws to the Pamunkey.

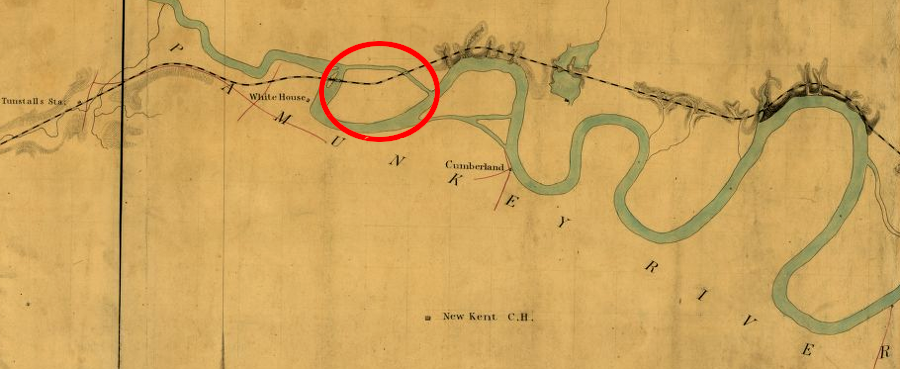

the Richmond and York River Railroad crossed the Pamunkey Reservation, east of White House

Source: Library of Congress, Richmond and York River Railroad (1864)

Virginia and local officials began to deal with the Mattaponi separately from the Pamunkey in 1894. The General Assembly defined 150 acres on the Mattaponi River as a separate reservation for the Mattaponi, and began the process of appointing a separate set of white trustees to handle legal matters.

The Pamunkey were assertive about publicizing their distinctive history and culture at the time. Virginia officials were creating an enforcing new racial identity laws. The Jim Crow process of legal racial segregation was a threat to those in Virginia who viewed themselves as "not white" and "not black."

The Pamunkey response was to highlight their ties to the founding of Virginia in 1607, linking their heritage to the founding English colonists. Highlighting how Pocahontas saved John Smith may have been folk history, but linking the Pamunkey to the elite and powerful First Families of Virginia (FFV's) helped protect their community from the threats of segregation. The Pamunkey participated at the Chicago World Fair in 1893, while the Mattaponi chose to stay out of the limelight and to separate themselves.6

during the Jim Crow era, the Pamunkey advertised their identity and their persistence in Virginia since the days of Powhatan and Pocahontas

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Group of Eight in Dance Costume 23 OCT 1899

Today, the Pamunkey Reservation consists of 1,200 acres. That is 7% of the land originally granted by the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation.7

A mound on Pamunkey Neck is described as the gravesite of Powhatan. He died around 1618, and the ceremony for the "taking up" of his bones was a signal for the uprising that initiated the Second Anglo-Powhatan War in 1622. Colonists did not know the details of Powhatan's death or burial, so the written records do not document the location of his grave.

His bones may have been placed in a mat and kept in the Uttamusak temple complex, rather than interred in the ground. Whether or not Powhatan's remains ended up on what is today the reservation, highlighting the association with the paramount chief and father of Pocahontas gives the Pamunkey tribe special status today.

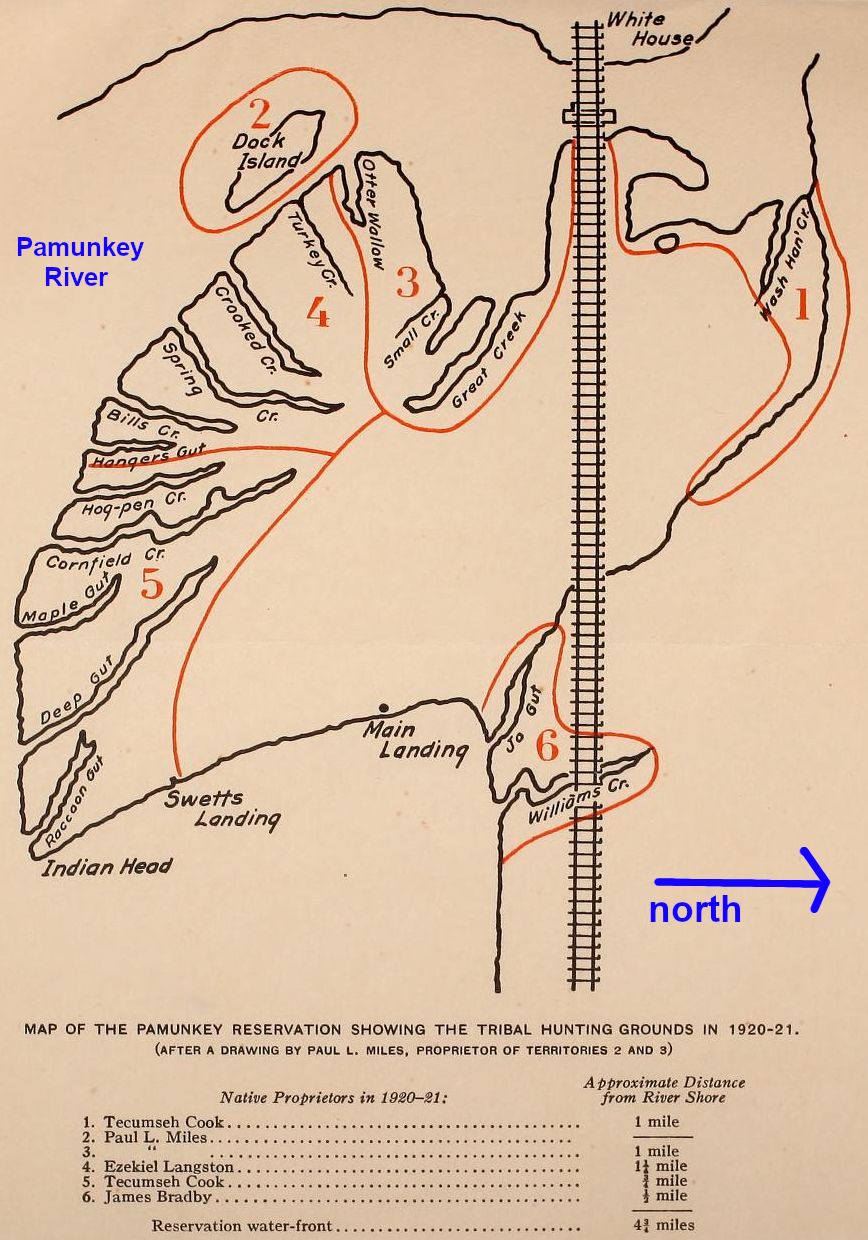

ethnographer Frank Speck recorded the reservation was divided into traditional hunting tracts ("north" is to the right)

Source: Museum of the American Indian, Chapters on the ethnology of the Powhatan tribes of Virginia (pp.314-315)

Federal recognition of the Pamunkey tribe in 2015 did not alter the boundaries of either reservation in Virginia. Recognition did open the door, slightly, to the potential of the tribe to offer some form of gambling on the reservation.

That potential is unique in Virginia. Six other Virginia tribes were Federally recognized by an act of Congress in 2018, but the bill included a ban on gaming:8

Procedures based on the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act could lead to a casino on the Pamunkey Neck reservation. Class III gaming, complete with slot machines and games of chance such as craps and roulette, would required three steps:8

That risk was great enough for the MGM corporation, which operated a casino in Maryland, to oppose Federal recognition of the tribe.9

The tribe chose instead to propose building a $700 million casino, hotel and spa elsewhere in eastern Virginia, with private partners who would provide the needed funding. The Pamunkey planned to work with the Middle Peninsula Planning District Council to find a site on territory that was formerly within Tsenacomoco, and where local governments would support economic development based on gambling.

The site would be designated as "trust" land and added to the reservation, even though it would not be adjacent to the current reservation on Pamunkey Neck. Once the tribe and state signed a compact establishing ground rules for revenue distribution, then slot machines, roulette wheels, and card games such as blackjack would be regulated by the National Indian Gaming Commission. If the state was unwilling to sign a compact, the tribe could still offer Class II gaming - bingo and card games based on skill rather than chance, such as poker.10

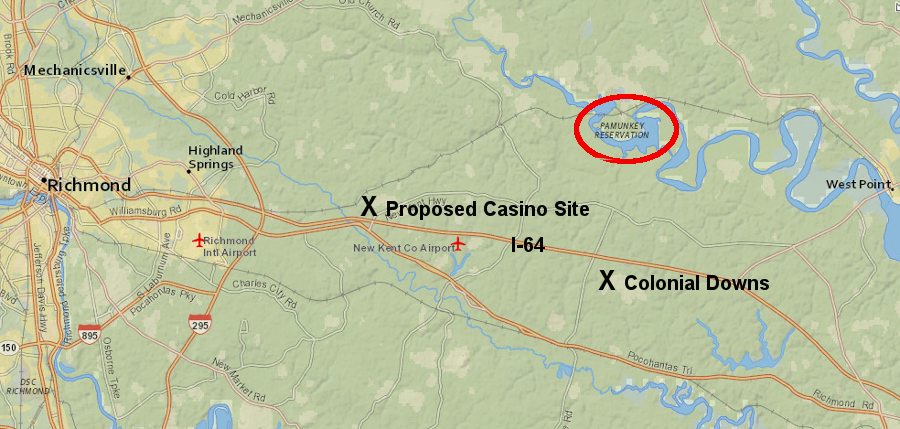

The Pamunkey and a billionaire who had become wealthy by selling video games to Native American casinos, venture capitalist Jon Yarbrough, announced in 2018 that he had purchased 610 acres east of Richmond at the Exit 205 interchange on I-64. He paid over $3 million for land that was in New Kent County, on the north side of Exit 205 and just east of the Chickahominy River. The Pamunkey indicated they would consider locating a casino there, or at other locations.11

an Illinois-based video gaming operator purchased 600 acres along I-64 east of Richmond as a potential site for a Pamunkey-owned casino and resort

Source: Daily Press, Pamunkey Indian Tribe associates buy New Kent land for possible resort, casino site

A casino at the I-64 interchange would place a Pamunkey-based gambling center in direct competition with Colonial Downs. Prior to the Pamunkey's announcement about their casino plans, the 2018 General Assembly had loosened restrictions on video gaming at the former racetrack. The tribe carefully avoided the limelight during the debate over authorizing more gambling opportunities, so the focus stayed on economic advantages to the state and not on "identity politics."

Despite moral opposition to gambling by many voters, the legislators considered it a higher priority to incentivize a new owner to re-open Colonial Downs. The potential new owner, Revolutionary Racing, was not associated with the Pamunkey.12

The tribe did not commit to any project at the Exit 205 interchange when the land purchase was revealed. The Pamunkey kept open the possibility that they might negotiate a deal to locate at some other site, including the Colonial Downs racetrack. A partnership with the tribe might enable Revolutionary Racing to offer Class III gaming. Other locations ranged from Hampton Roads to Richmond, with the chief commenting:13

two gambling centers have been proposed on I-64 east of Richmond, one by the Pamunkey tribe and one at the former Colonial Downs racetrack

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Wherever it might be located, the political approval process for the new casino/resort will involve Federal, state, and local officials.

New Kent County will benefit if either Colonial Downs or a Pamunkey casino/resort are developed and remain open. There could be local support for authorized gambling at both sites, but county officials could decide that only demand is limited and only one site will be economic. The county could choose to support just one facility, either re-opening Colonial Downs or building a new resort.

Indian gaming politics are especially complicated if the site is not located within the boundaries of the reservation of a Federally-recognized tribe. In Connecticut, plans by the Mohegan and Mashantucket Pequot tribes to build an off-reservation casino were blocked by top officials in the Department of the Interior in 2017, apparently after lobbying pressure applied by competitor MGM Resorts International. The Bureau of Indian Affairs staff had endorsed the project, but final Federal approval was not granted.

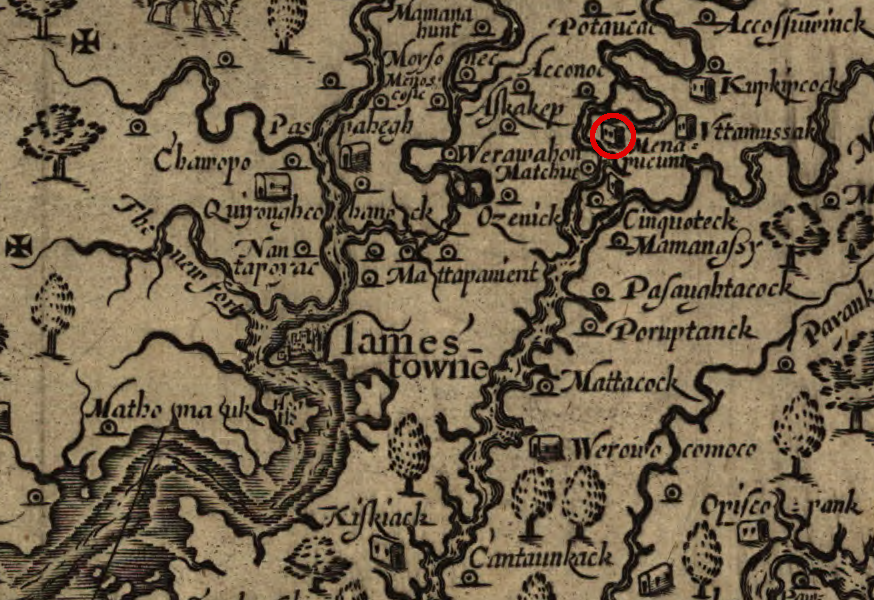

When the English arrived in 1607, the towns of the Pamunkey were far away from Hampton Roads and north of where I-64 is now located. The Bureau of Indian Affairs may reject an application to take land into trust, if the site was not part of the tribe's ancestral territory.

John Smith recorded where different tribes lived, including the Pamunkey north of the Pamunkey River (and outside boundaries of modern New Kent County)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

Everyone who lived in Tsenacomoco did not live on "Pamunkey" land. The Chickahominy controlled the Exit 205 interchange and Colonial Downs areas in New Kent County.

Powhatan's paramount chiefdom did not incorporate the Chickahominy until the end of the First Anglo-Powhatan War. Until then, the Chickahominy were governed by a council of elders and admitted no allegiance to Powhatan. Opechancanough convinced the independent tribe that the colonists were a greater threat, and the Chickahominy dropped their treaty with the English.

The Pamunkey may claim that all the land controlled by the 30+ tribes within Powhatan's paramount chiefdom was their "ancestral" land. Powhatan was born at a town just east of Richmond, at a site now located on the Tree Hill Farm plantation.14

the location of Powhatan's birth, the town of Powhatan, is today

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

There is no guarantee that the Bureau of Indian Affairs would agree with such a broad claim of ancestral "Pamunkey" land. The Federal agency must accept trust responsibility for lands before a casino could be located off the reservation in Hampton Roads, New Kent County, or Richmond.

Other Native American tribes may also disagree with a broad claim of "Pamunkey" land.

The Chickahominy and the Eastern Chickahominy were recognized as distinct tribes by the state in 1983, and the Nansemond were recognized by the state in 1985. The US Congress granted Federal recognition to those three tribes in 2018, when it passed the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. The territory they occupied in the 1500's and 1600's, and still occupy today, was part of the paramount chiefdom led by Powhatan and Opechancanough - but those tribes do not describe their homelands as "Pamunkey" land.

the Pamunkey lands were north of the Pamunkey River, north of the Chickahominy and far from Nansemond territory

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman, 1670)

Virginia legalized casino gambling in 2020, so the Pamunkey did not need to get authorization for an off-reservation Class II gaming operation from the Secretary of the Interior. The Pamunkey negotiated a deal with Norfolk officials, becoming the preferred provider of casino services there. At one point, that included putting land between Harbor Park and the Amtrak station into trust, but the deal was revised to eliminate that provision.

Putting the land into trust would have minimized local authority, and opponents to the casino could have cited the Carcieri v. Salazar decision of the US Supreme Court. The judges determined that land acquired by a tribe which was not "under federal jurisdiction" in 1934 may not be taken into trust by the Bureau of Indian Affairs under the Indian Reorganization Act. Federal jurisdiction over the land is required before triggering the provisions of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and authorizing oversight by the National Indian Gaming Commission.15

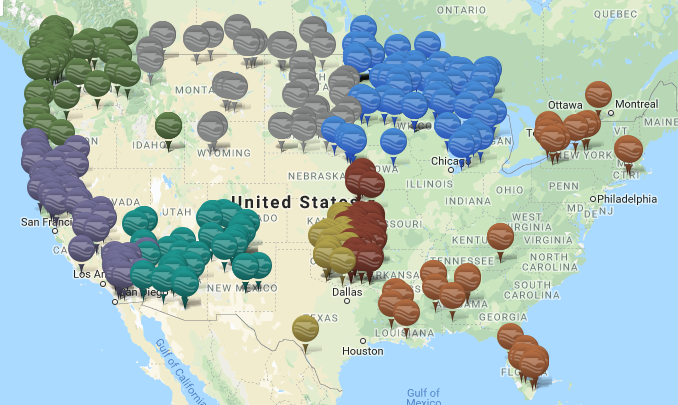

in 2018, there were no Native American gaming centers on the East Coast between Foxwoods Resort & Casino in Connecticut and Cherokee Tribal Bingo in North Carolina

Source: National Indian Gaming Commission, Map of Indian Gaming Locations

In 2020, King William County assessed the 1,000 acres in the Pamunkey Indian Reservation as worth $2.6 million, plus $1.1 million in improvements.16

the 1,000-acre reservation was assessed by King William County at $2.6 million in 2020

Source: King William County

Pamunkey tribal lands at the time of the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Map of King William County, Va.