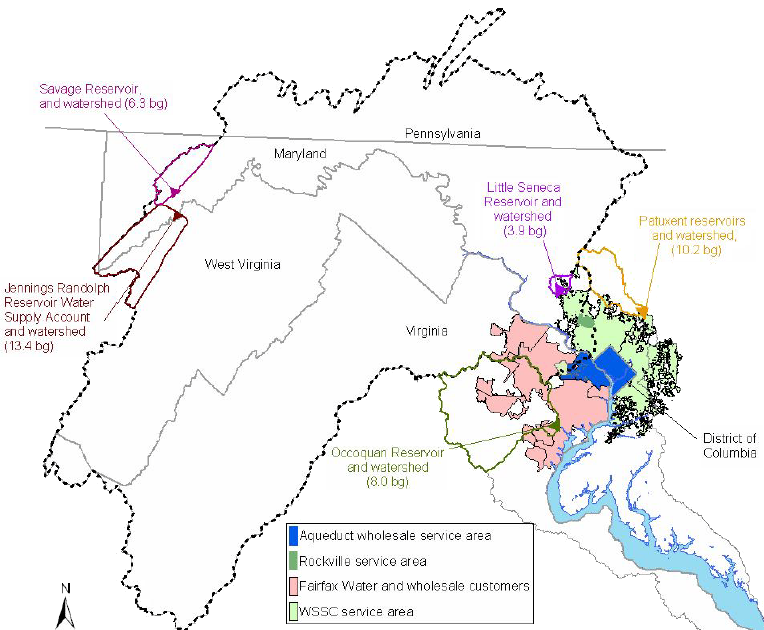

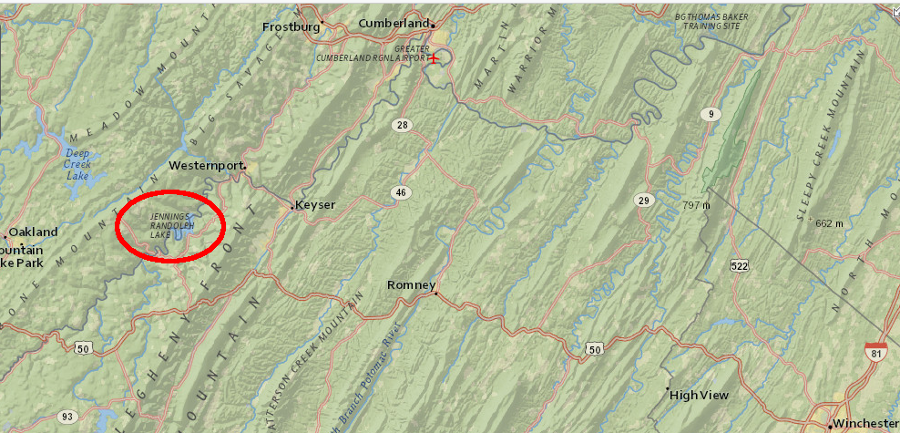

reservoirs have been built in West Virginia for Washington metropolitan area water suppliers

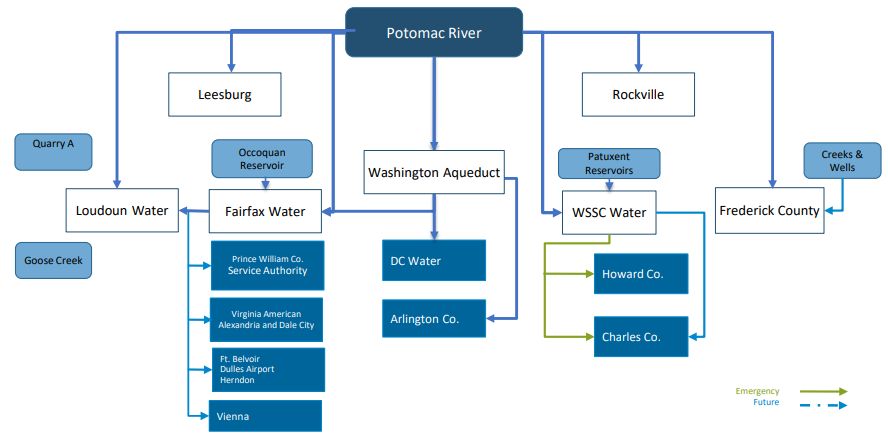

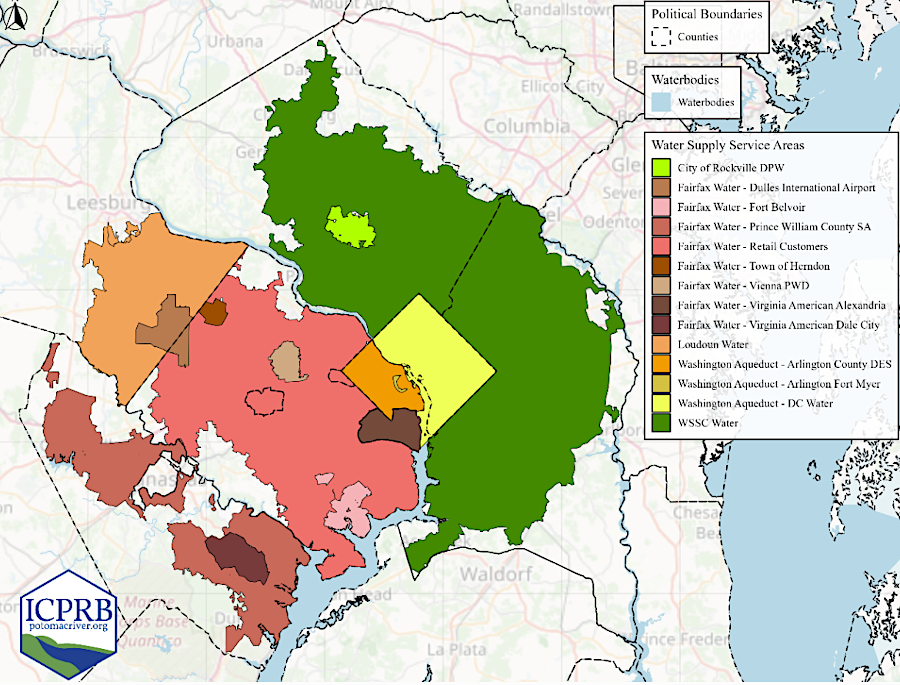

Source: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, 2010 Washington Metropolitan Area Water Supply Reliability Study (Figure 2-2)

reservoirs have been built in West Virginia for Washington metropolitan area water suppliers

Source: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, 2010 Washington Metropolitan Area Water Supply Reliability Study (Figure 2-2)

The Native Americans and early colonial settlers in Northern Virginia obtained their drinking water directly from springs, streams or the Potomac River. Hikers along the Appalachian Trail still rely upon springs and surface water sources, though hikers use some form of water treatment process to kill the omnipresent bacteria and harmful protozoa such as Giardia.

Wells were dug as plantations and "quarters" for slave-based agriculture developed in the 1700's. Town wells supplied residents when higher-density communities first developed. In 1921, nearly 300 municipal wells in Alexandria were used to supply domestic water to residents and firefighters when necessary:1

Starting in the 1850's, cities/counties developed complex systems for obtaining a reliable water supply, often damming streams outside the boundary of the jurisdiction where customers would be using the water. After over a century of water development that was based on building more, larger reservoirs as population increased, the long drought of the mid-1960's triggered another set of proposals for building 16 new dams on the Potomac River and its tributaries.

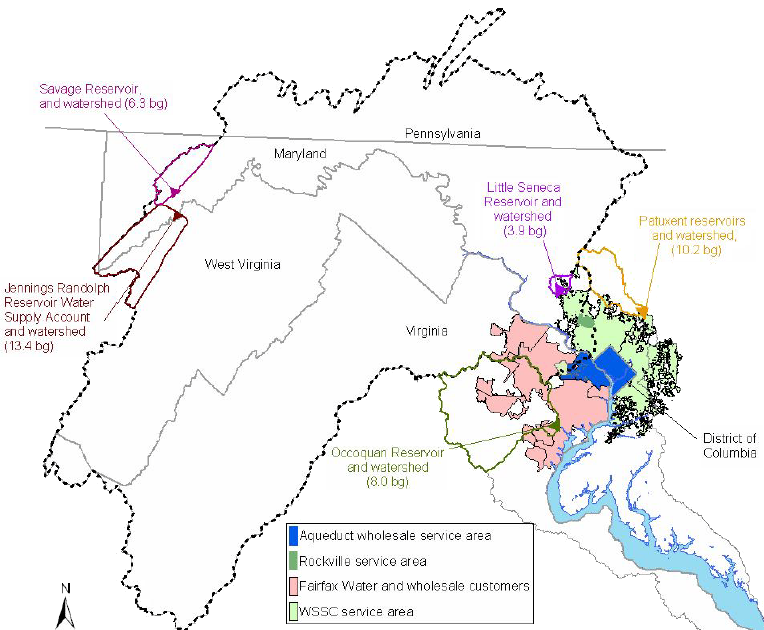

Proposals for new storage projects were constrained by public objections to environmental impacts. The US Army Corps of Engineers scaled back its dam construction proposals, and in the 1970's presented an alternative with just six dams. One, the Verona Dam, was as far away as Staunton.2

"six-pack" of dams recommended by US Army Corp of Engineers to increase water supply for Washington, including Verona Dam near Staunton

Source: US Department of the Interior, The Nation's River (digitized by Project Gutenberg)

Starting in the 1960's, public concerns about environmental changes increased enough to block new dams. The Corps finally shifted its focus on the Potomac River to non-structural solutions, including inter-jurisdictional cooperative agreements to increase the efficiency of water systems and to conserve water during periods of drought.

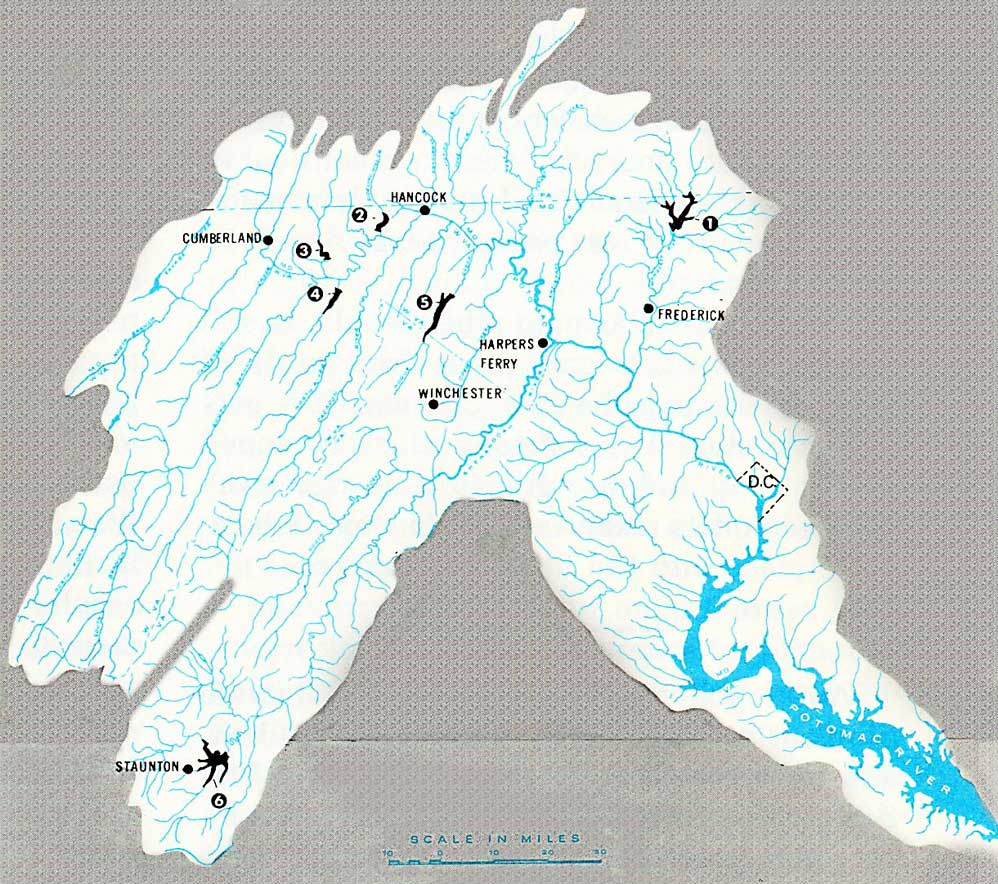

Only one of the "six pack" of dams proposed by the Corps was build. Completion of Bloomington Dam in 1981, blocking the North Branch of the Potomac River to form Jennings Randolph Lake, ended the old reservoir construction pattern. No more sections of the free-flowing Potomac River will be blocked by a dam.

the North Branch of the Potomac River was blocked by the Bloomington Dam in 1981

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Today, as described by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments:3

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, How It Works Ep1 Washington Aqueduct Final

Different Northern Virginia jurisdictions created separate systems for storing, treating, and delivering drinking water to their citizens, as the jurisdictions developed at different times. Northern Virginia did not plan and implement a regional, efficient water system based on predictions of where population would grow in the Twentieth Century.

Water systems, like sewer systems, are affected by economies of scale. The bigger the system, the cheaper it is to produce each gallon of drinking water. In the long-term, costs could have been minimized and reliability increased if a regional system had been constructed, with expansions triggered at different levels of demand.

Cities and counties are separate jurisdictions in Virginia, and often developed separate utility systems. In Northern Virginia, cities and counties have competed with each other for economic development and failed to develop a integrated approach to provide utilities. All fragmented water systems were connected only after the 2005 drought, to improve reliability.

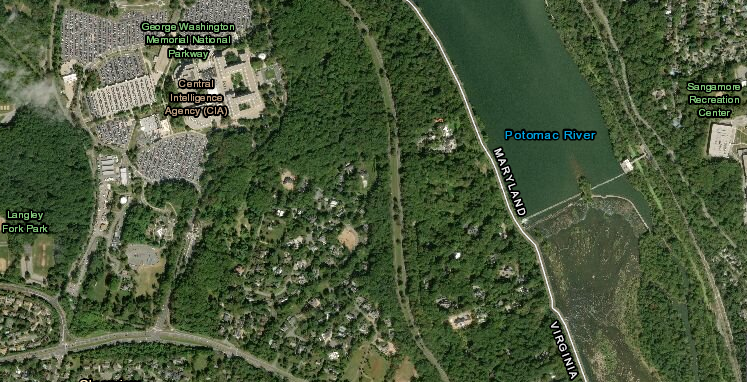

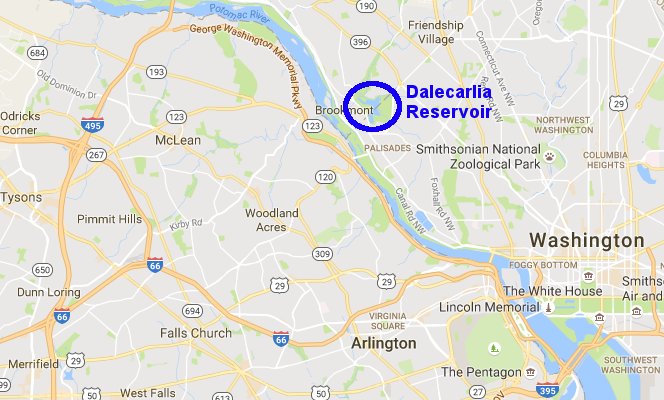

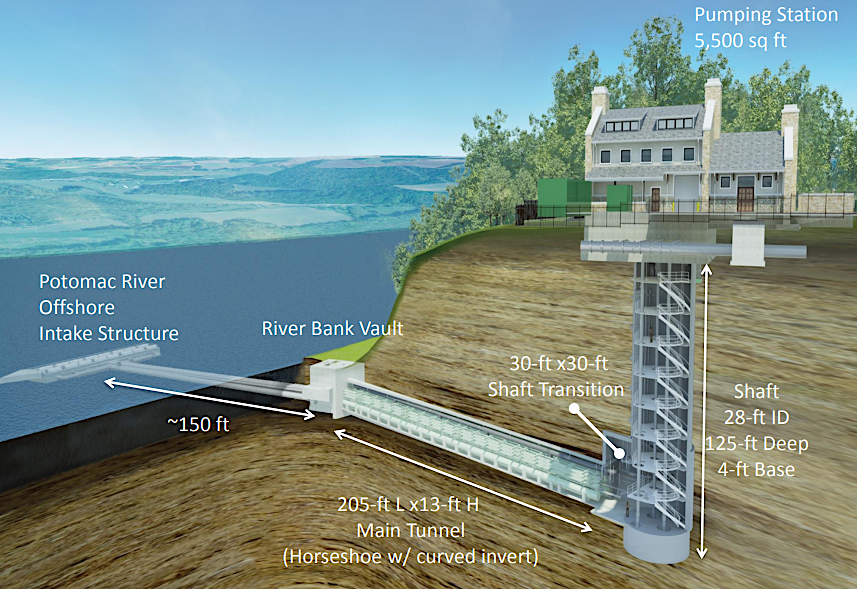

Arlington County and the City of Falls Church were able to start their water utilities by expanding on existing infrastructure, and still get most of their treated drinking water from the same system that services the District of Columbia. The Washington Aqueduct Division of the Army Corps of Engineers diverts Potomac River water at Great Falls and at Little Falls, before the river reaches sea level and the fresh water becomes brackish.

After treatment at the Dalecarlia Reservoir, the majority of the water goes into the District of Columbia. Some is pumped through pipes underneath the Potomac River to supply a portion of Northern Virginia. Acts of Congress authorized the Corps of Engineers to supply water to Arlington County in 1926, and to Falls Church in 1947. In 1959, the Corps built another dam across the Potomac River and a pumping station at Little Falls, plus a pipe to Falls Church to supply water to that jurisdiction.

some of the water from the Potomac River that is diverted at Little Falls and pumped to Dalecarlia Reservoir for treatment ends up in Northern Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Town of Vienna operates its own water distribution system. The town supplies water to its residents, plus some customers in Fairfax County on the periphery of the town's border.

Vienna bought most of its treated drinking water from Falls Church, which relied upon the US Army Corps of Engineers system. A portion of the town's treated drinking water was supplied by Fairfax Water.

When Fairfax Water acquired the water system of Falls Church in 2014, the county became the town's only water supplier. Fairfax Water offered to absorb the entire water distribution, billing, and customer support responsibilities, but the Town of Vienna declined the offer.

In 2024, however, the town and county began talking again about consolidating operations. At the time, Vienna was charging $6.40 per 1,000 gallons while Fairfax Water was charging its customers $3.65 per 1,000 gallons. Customers living in Fairfax County, but supplied by the town, paid significantly more for the same water than neighbors who dealt directly with Fairfax Water.4

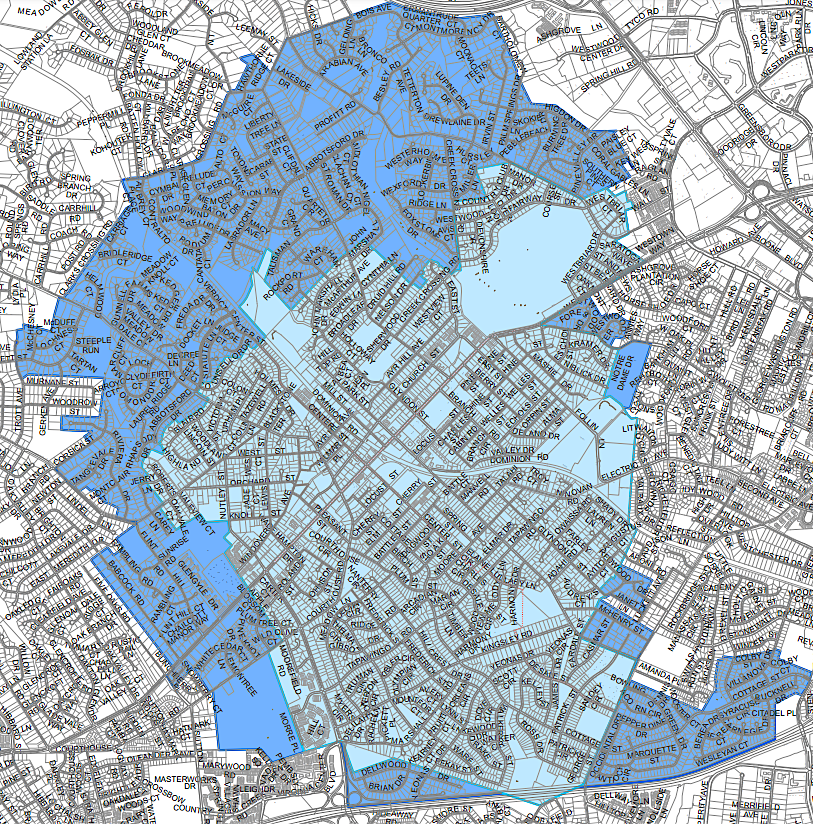

Vienna provides drinking water to town residents (light blue) and some Fairfax County residents (dark blue) - who must pay the higher rates charged by the town

Source: Town of Vienna, Water Distribution System Map

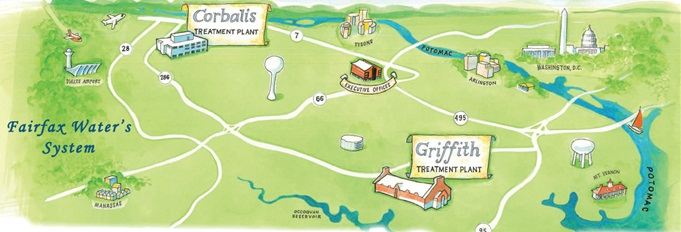

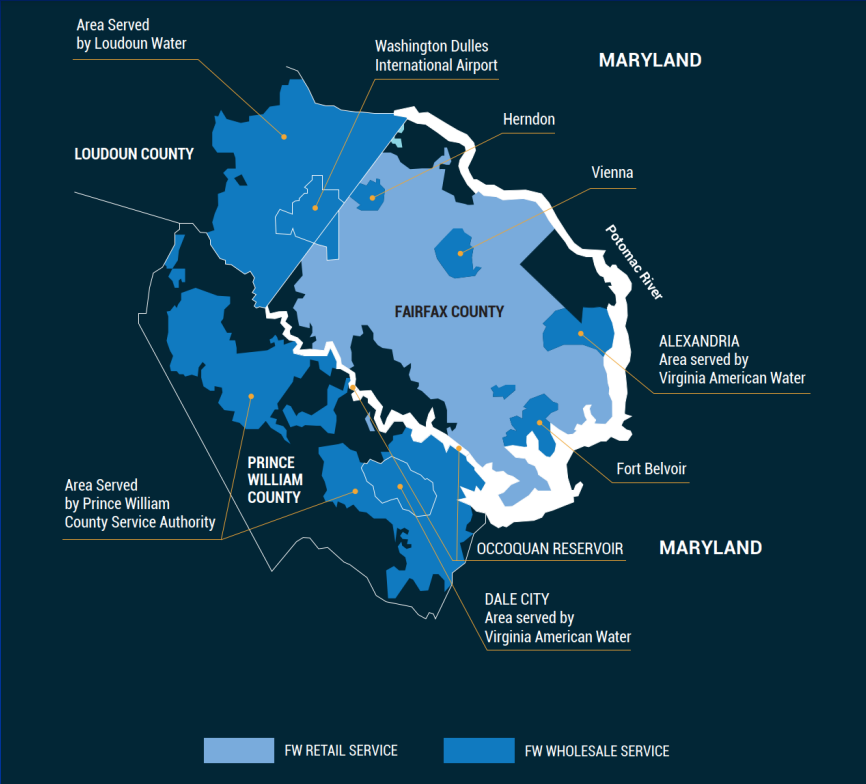

Fairfax Water gets raw water from both the Potomac River and the Occoquan Reservoir. The water from the Potomac River is processed to meet drinking water quality standards at the Corbalis Treatment Plant in Loudoun County, which can produce 225 million gallons/day of drinking water.

The facility, located near Herndon, discharges the waste material it extracts from Potomac River water into a tributary of Sugarland Run. During a drought in 2024, algae increased in the river. The organic-rich discharge generated complaints about smells from nearby residents. In response, the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors directed that Fairfax Water and county staff explore discharging into the county's sewer system so it would be treated at the wastewater treatment plant, just like the sewage generated at the Corbalis Treatment Plant.

the Corbalis Treatment Plant is next to Herndon, nearly five miles south of the water intake in the Potomac River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

When that facility opened in April 1982, it was built to produce 50 million gallons/day, with a water intake and pump station on the shoreline of the Potomac River. In 1997 the Fairfax County Water Authority proposed a new intake location in the middle of the river, which required building a pipe to access the cleaner water. Maryland officials objected to the extension, claiming that a state permit was required because the pipe would be placed on the state-owned bed of the Potomac River.

Maryland highlighted that the extension was required because muddy runoff at the shoreline was caused primarily by stormwater runoff from housing development authorized by Loudoun County. Fairfax County wanted to take advantage of the land use planning decisions made by Maryland to protect water quality of the Potomac River, without compensation for those efforts. The US Supreme County resolved yet another dispute over the Maryland-Virginia boundary. In 2023 it ruled that Maryland owned the riverbed,. but based on previous state compacts and court decisions Fairfax County was not obligated to get a State of Maryland permit.

Source: Fairfax Water, Corbalis Water Treatment Plant Tour

The water drawn out of the Occoquan River is fresh, in contrast to the brackish Potomac River nearby at Lorton. The Griffith Treatment Plant can generate 120 million gallons of drinking water/day from the Occoquan River.5

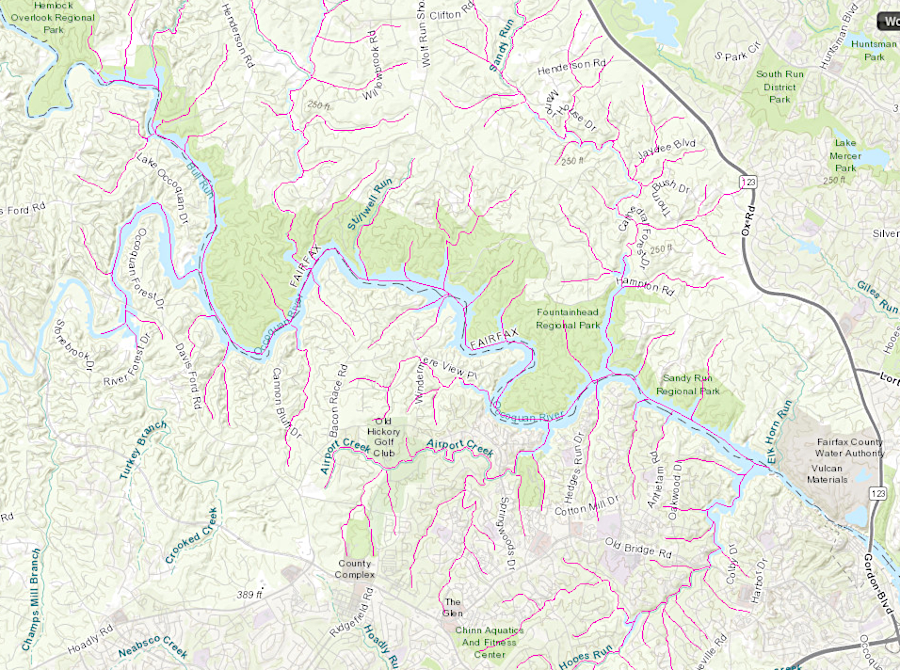

red lines identify tributaries considered as most important source waters to protect, for drinking water supply in Occoquan Reservoir

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), VEGIS

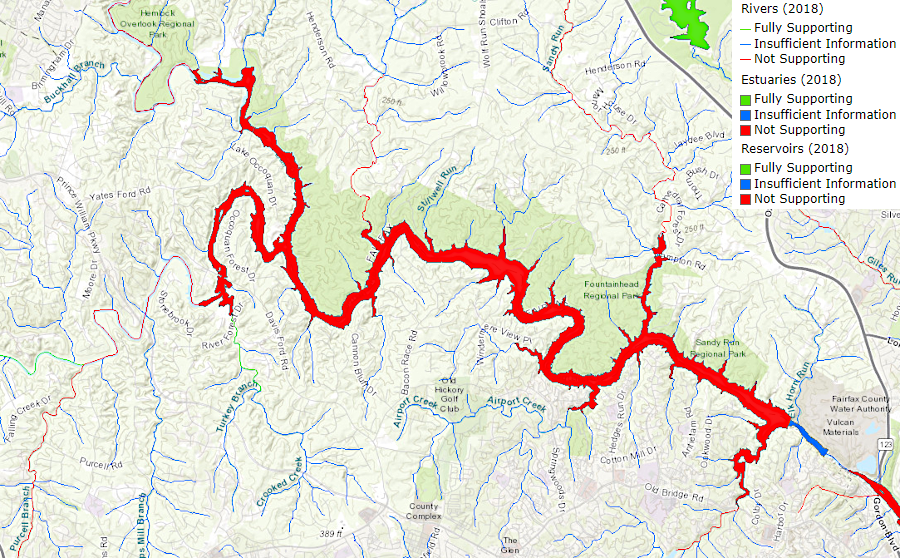

red lines identify impaired waters that do not meet water quality standards and are on the "dirty water list" - 305(b)/303(d) Water Quality Assessment Integrated Report

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), VEGIS

The raw water extracted from the Occoquan Reservoir has also been "used" by people living upstream. In the summer months, a high percentage of the water in Bull Run flowing into the Occoquan Reservoir is treated sewage. What was flushed in Manassas, Centreville, and other areas nearby was processed in the Upper Occoquan Service Authority (UOSA) wastewater treatment plant south of Centreville, then discharged into Bull Run west of Route 28.

When customers turn the tap in southern Fairfax County, eastern Prince William, and Alexandria, they drink re-processed sewage from the cities of Manassas/Manassas Park and from Prince William/Fairfax counties.

People drinking water from the Potomac River, extracted upstream of Fairfax County and processed at the Corbalis Treatment Plant, are also getting some reprocessed sewage. That wastewater comes from places even further upstream, including wastewater treatment plants as far away as Winchester and Staunton.

Fairfax Water processes raw water from the Potomac River at the Corbalis Treatment Plant in Loudoun County, and raw water from the Occoquan Reservoir at the Griffith Treatment Plant near Lorton

Source: Fairfax County, Where Does Drinking Water Come From?

The 5% of drinking water not supplied by the three major water supply agencies in Northern Virginia comes mostly from individual wells and small community systems for isolated subdivisions. In addition, the City of Manassas maintains an independent system, and sells processed drinking water to the Service Authority in Prince William County.

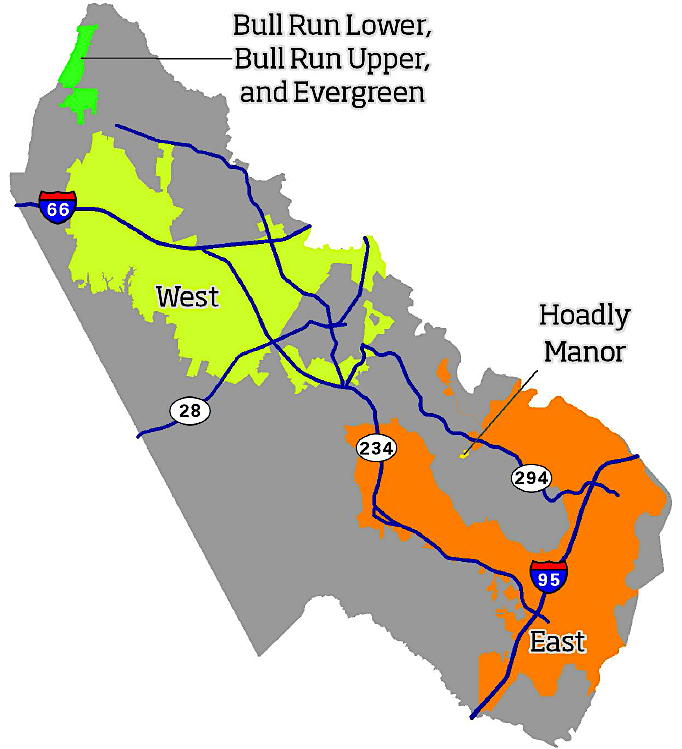

Prince William Water (known until 2024 as the Service Authority) has several separate distribution systems. The western system distributes water purchased from Fairfax and Manassas, while the eastern system distributes water purchased from just Fairfax. Small communal water systems distribute water supplied from wells to subdivisions on Bull Run Mountain, at Evergreen, and at Hoadley Manor.

Prince William Water purchases treated water from Fairfax Water to supply Potomac River water to western Prince William County, and purchases water from the Occoquan Reservoir for the eastern end

Source: Prince William Water, Water Quality Reports

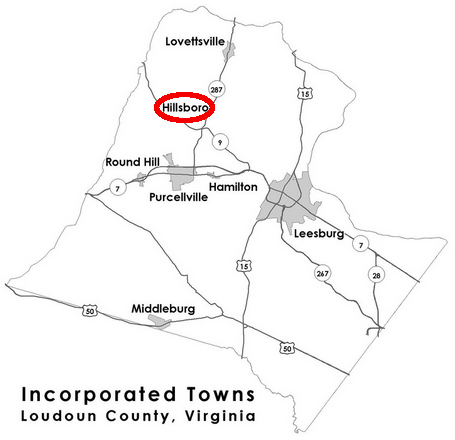

Small systems can be very expensive to operate. The Town of Hillsboro in Loudoun County initially used Hill Tom Spring as its water supply, then replaced it with a well-based system. After the Virginia Department of Health required the town to close down its well, Hillsboro drilled several new ones before finally discovering a location that produced 20-25 gallons per minute.

The Hillsboro water system had only 40 customers, totaling roughly 100 people. The replacement system with new pipes, storage tanks, and water treatment facilities would cost $1.9 million. Even after a grant from the state for 1/3 of the cost, each customer would have to finance nearly $32,000 in costs to build the replacement system.

Loudoun County came to the rescue in 2014, arranging financing so the customers had to fund only $100,000 of the total replacement system. The streamlined final proposal still cost $1.7 million, which the mayor described succinctly:6

in 2014, Loudoun County helped finance a new water system for Hillsboro

Source: Loudoun County Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Incorporated Towns, 2009 (Map Number 2009-193)

Purcellville created its public water supply after World War I, acquiring Harris Spring, Potts Spring, and Cooper Spring on Short Hill Mountain and creating the J.T. Hirst Reservoir in 1955. It ended up acquiring 1,272 acres, which the town protected via a conservation easement in 2009.7

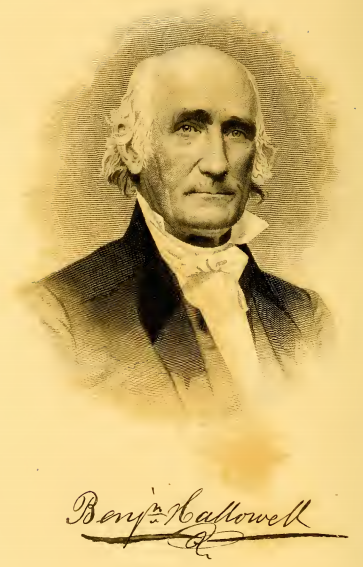

Benjamin Hallowell initiated development of the Alexandria Water Company in the early 1850's

Source: Autobiography of Benjamin Hallowell

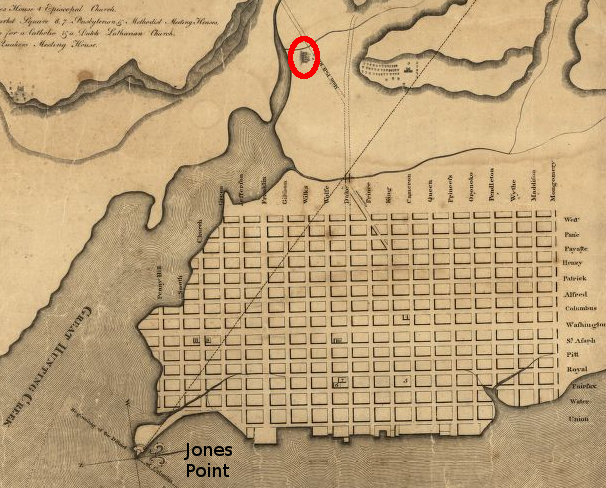

The first major water system to be developed in Northern Virginia was a local system designed to supply Alexandria. Prior to that project, Alexandria residents relied upon wells and cisterns, including at least one designed with alternating levels of charcoal, sand and/or gravel to filter the rainfall to improve water purity:8

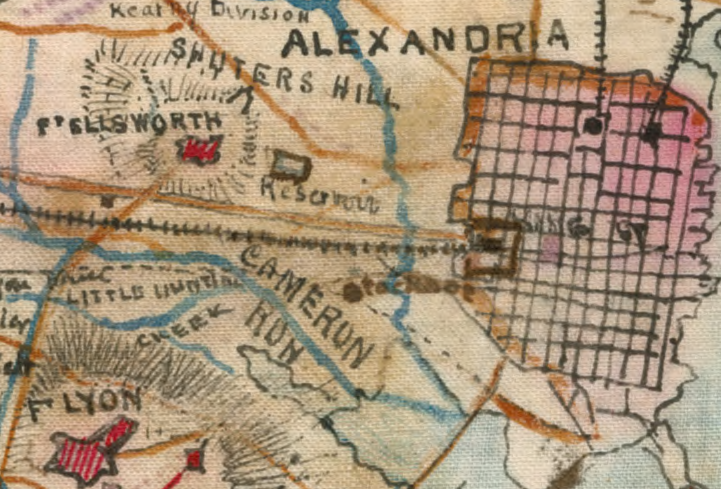

Benjamin Hallowell, a Quaker from Pennsylvania, came to Alexandria in 1824 (when it was part of the District of Columbia) to start a private boarding school. In 1851, he organized the Alexandria Water Company to pump water from Cameron's Run to a reservoir on Shuter's Hill, and gravity then produced the water pressure to supply customers.

when the Union Army built Fort Ellsworth on Shuter Hill in 1862, the reservoir location was recorded

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Alexandria, Virginia by Robert Knox Sneden

Hallowell had seen such a system in operation, with a mill pumping the water used in New Holly, New Jersey. The engineer Hallowell hired to build the system altered the original location of the planned reservoir, moving it lower to minimize the energy required to pump water up from Cameron Run and to reduce the threat of pipes breaking due to excessive water pressure.9

after 1851, Cameron Mills, in the West End of modern Alexandria, pumped water into the new Alexandria Water Company reservoir on Shuter's Hill

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the town of Alexandria in the District of Columbia, 1798 (by George Gilpin)

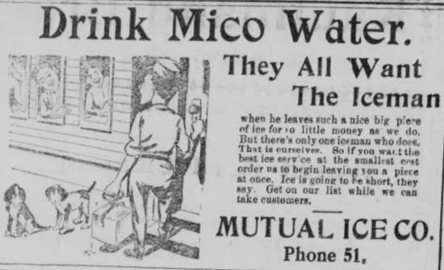

Portions of Alexandria continued to rely upon wells, in addition to the water pumped out of Cameron Run. Starting in 1900, the Mutual Ice Company (MICO) delivered ice from the plant on Cameron Street to Alexandria residents, when ice boxes kept food cool in the days before electricity-powered refrigerators. MICO also produced vast quantities of ice for cooling Fruit Growers Express and other railroad cars shipping perishable items, stocking the cars as they were classified into trains after Potomac Yards was built in 1906. Wells 280-500 feet deep supplied the water used for making the ice.10

MICO Water used well water to make ice to refrigerate railroad cars in Potomac Yard

Source: Library of Congress - Chronicling America historical newspapers, Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser (September 8, 1909)

In 1851, a fire in the U.S. Capitol burned 35,000 books in the library, including 2/3 of the books purchased from Thomas Jefferson to restock the Library of Congress after the British burned it in 1814. The fire demonstrated that firefighters did not have an adequate water supply. The Congress then authorized the US Army Corps of Engineers to build the Washington Aqueduct system. The national capital needed cleaner water as well as a more-reliable supply. President William Henry Harrison died a month after his inauguration from what may well have been gastroenteritis. The water supply for the White House in 1841 was seven blocks away from where sewage from District of Columbia was discharged into the marsh.

General Montgomery Meigs managed the construction of the Washington Aqueduct between its beginning in 1853 and completion 11 years later in 1864. A diversion dam was built above Great Falls, plus a 12-mile pipe that was 9 feet in diameter. Much of the pipe was located beneath the new Conduit Road, now known as MacArthur Boulevard. Water flowed by gravity to the "receiving reservoir" now named Dalecarlia Reservoir. A "distributing reservoir" was constructed in Georgetown.

The dam at Great Falls initially stretched from the Maryland shoreline only halfway into the Potomac River. To ensure a greater supply of water, the dam was extended to the Virginia shoreline between 1884 and 1885.

A second conduit with three interconnections was completed in 1923, increasing the supply. The only treatment was allowing solids to settle out at the receiving reservoir, and a reporter described the drinking water as a "[s]eal-brown mixture of water and real estate." The McMillan Sand Filtration Plant was completed in 1905, and was designed to filter out bacteria by trickling raw water slowly through a thick layer of sand. A rapid sand filtration system, relying in part upon chemicals, was constructed at the Dalecarlia Reservoir in 1928.

the Potomac River is a source of drinking water for Arlington County and the City of Falls Church, after initial treatment by the Army Corps of Engineers at the Dalecarlia Reservoir

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Washington Aqueduct still provides clean water from the Potomac River for Washington DC. After completion of the Dalecarlia Water Treatment Plant in 1928, Northern Virginia began to receive clean drinking water from the system operated by the Corps of Engineers.11

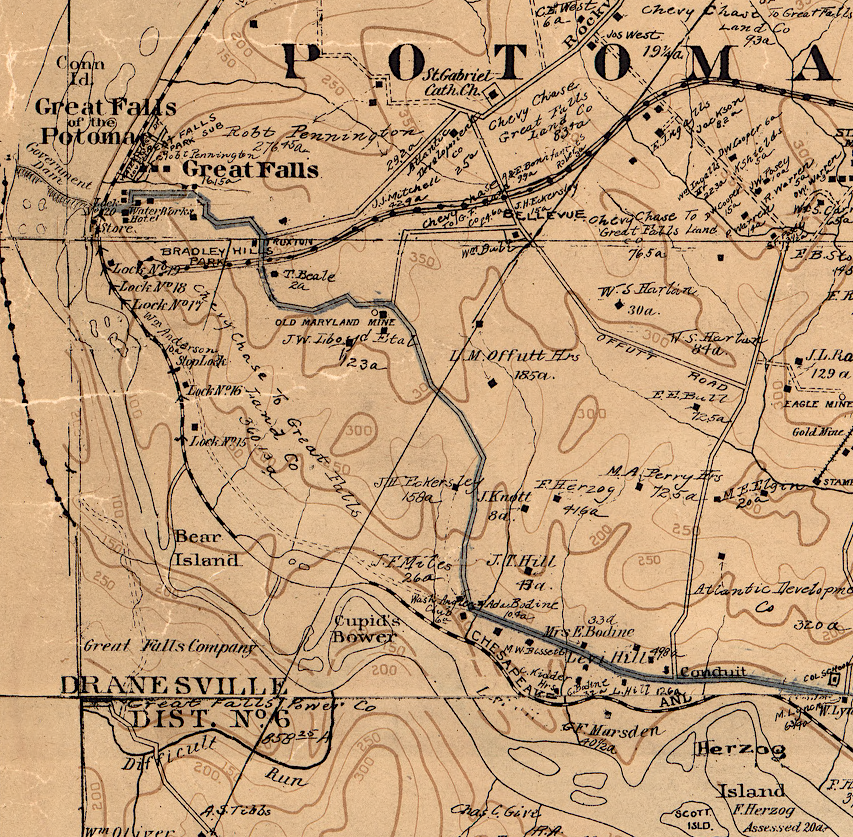

the District of Columbia gained a reliable freshwater supply by damming the Potomac River above Great Falls

Source: Library of Congress, Baist's map of the vicinity of Washington D.C (1918)

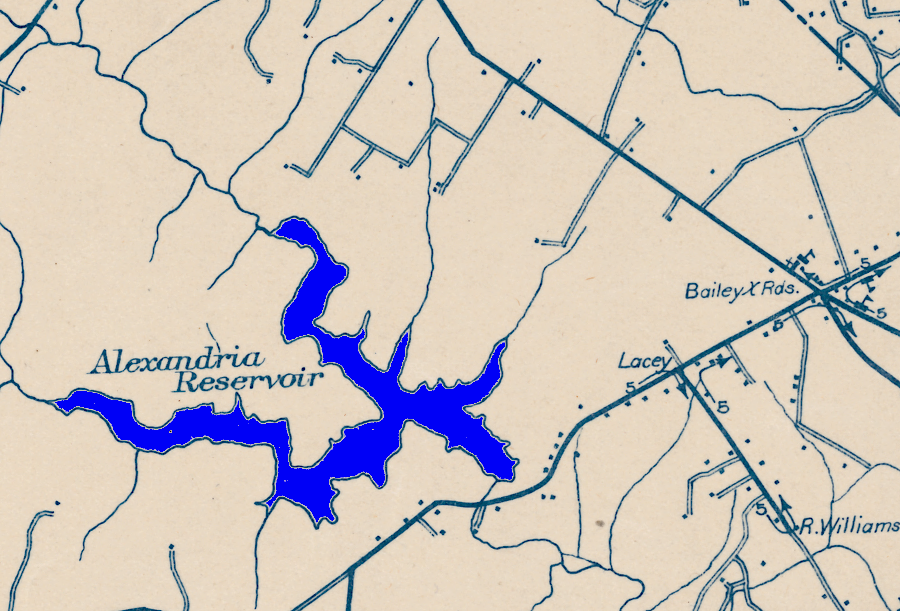

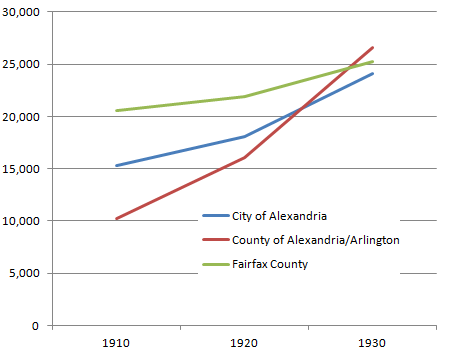

The population of Arlington County (known as Alexandria County between 1847-1920) grew substantially after World War I, and the demand for water increased. The Alexandria Water Company built a reservoir in 1915 to expand the supply of water to the city of Alexandria, which annexed over 2,000 acres from Alexandria/Arlington County in 1915 and 1929.

the Alexandria Reservoir is now known as Lake Barcroft

Source: Library of Congress, 12

after World War One, Arlington County tapped into the District of Columbia water system to accommodate demand from rapid population growth

Source: University of Virginia Library, Historical Census Browser

Before the Town of Fairfax incorporated in 1961 and became the independent City of Fairfax (and thus a separate jurisdiction from the County of Fairfax), it built the Goose Creek Reservoir in Loudoun County to make sure that the new city would have its own water supply.

Converting the Town of Fairfax into an independent city, separating it from the county, was controversial. If the new city had relied upon the county for water, then the county would have retained leverage to control land use decisions and limit the economic growth of the city. County control over the water supply would have constrained the ability of City of Fairfax officials to make economic development and land use decisions that might compete with county objectives.

When the Town of Fairfax proposed development of the Goose Creek Reservoir, Loudoun County opposed export of Goose Creek water outside the county. Loudoun County attempted to block the "water grab" by a separate jurisdiction, but ultimately settled its lawsuits and relied upon the City of Fairfax system to supply the Town of Leesburg and nearby customers. In 1982, Leesburg built its own Kenneth B. Rollins Water Treatment Plant (named after the mayor at that time) to process water pumped directly from the Potomac River.

Loudoun also signed long-term contracts with the Fairfax County Water Authority (now Fairfax Water) to obtain drinking water for the development of the eastern part of the county.13

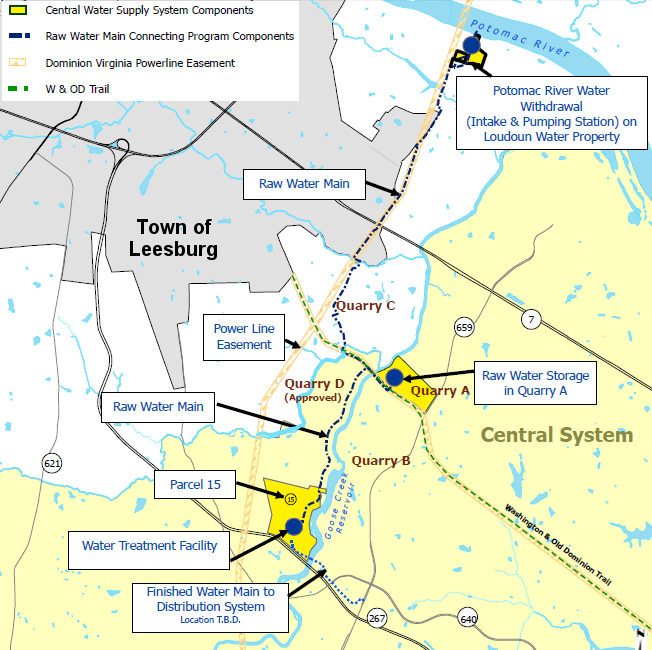

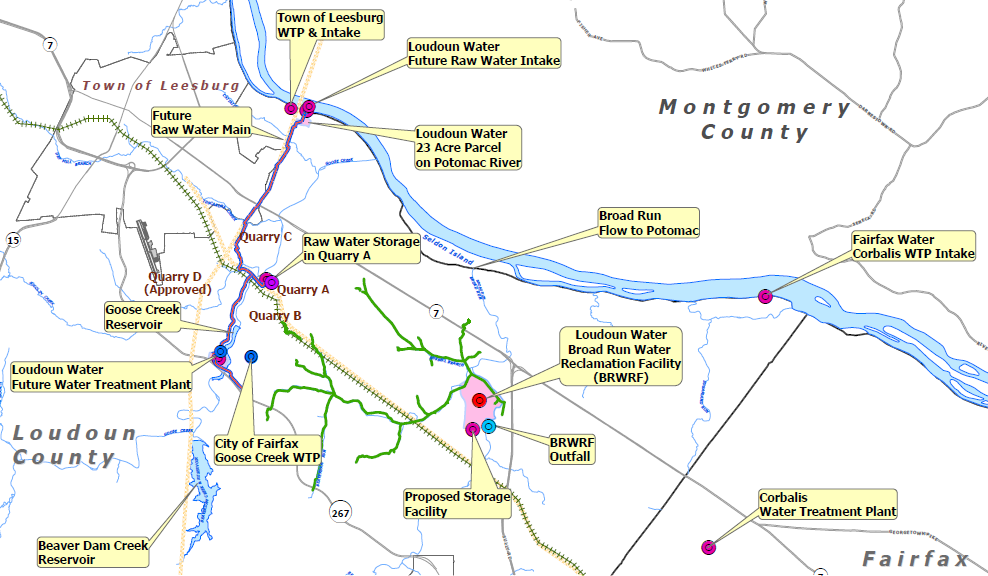

Loudoun County ultimately decided to create an independent system. In 2012, after suburban development had transformed land use patterns near Dulles Airport in particular, Loudoun County decided to develop its own separate water system that would also rely upon the Potomac River as the source, storing wintertime surplus flow in former quarries.

After examining multiple options, it developed plans to withdraw water from the Potomac River during periods of high flow, store the water in old quarries, and pump the water from the quarries to a new drinking water treatment plant built on Goose Creek:14

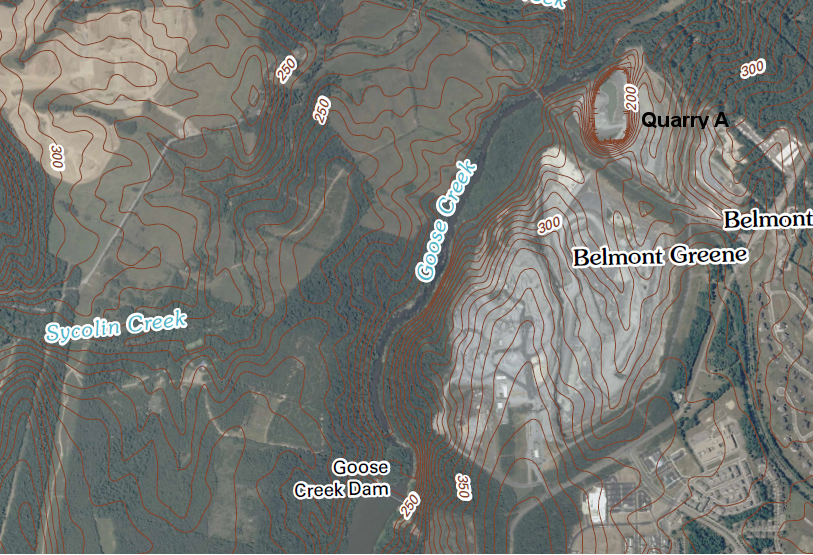

different quarries were studied as potential storage sites for Loudoun County's new drinking water system

Source: Loudoun Water, A safe, reliable water supply for generations - Vicinity Map

The Luck Stone quarry on Goose Creek (Quarry A) was finally chosen. Once rock removal is ended there around the year 2020, the hole in the ground will be repurposed to store one billion gallons of Potomac River water. Reutilizing a second quarry may allow greater storage at a later date.

Loudoun Water will use a quarry just downstream from Goose Creek Dam as its storage site for banking Potomac River water

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Leesburg 7.5x7.5 Topographic Quadrangle (2011)

Loudoun Water planned to eliminate its need for water from City of Fairfax gradually. However, in 2014, Fairfax Water acquired the City of Fairfax's water utility system, after the city determined the cost of upgrading its facilities exceeded the benefits of independence from the county. Fairfax Water had an adequate supply of raw water and facilities to process it into safe drinking water, so the city's facilities in Loudoun County were surplus.

Loudoun Water then purchased the Goose Creek Reservoir, Beaverdam Reservoir, and the City of Fairfax's old water treatment plant for $30 million. The purchase gave Loudoun the immediate capacity to generate 11 million gallons/day of drinking water and distribute it to the eastern edge of the county, using the old City of Fairfax pipeline.

For Loudoun officials, the major benefits from the purchase were the ability to control costs and ensure adequate supplies, without having to depend upon a separate political jurisdiction (or private company...) as a key supplier. Roughly 60 years after the City of Fairfax concluded it needed an independent water system to compete with adjacent Fairfax County, Loudoun County reached the same conclusion. The General Manager of Loudoun Water said:15

Loudoun Water will meet a portion of its projected 90 million gallon/day (MGD) demand through water banking

Source: Loudoun Water, Potomac River Water Supply Project Summary (p.4)

The Town of Manassas built Lake Manassas in 1971, and piped water through Prince William County to supply city customers. Like the City of Fairfax, Manassas imported its water from outside the town's boundaries; all the water that flows into Lake Manassas comes from Fauquier and Prince William counties - not a drop of water in the reservoir originates within the boundaries of Manassas. In 1971, Manassas was still a part of Prince William County, so there was no serious political conflict about a "water grab" at that time.

Manassas became an independent city in 1975, splitting off from the county. The city's water source, Lake Manassas, remains within the political jurisdiction of Prince William County, but the city owns the lake and much of the adjacent shoreline. At times, Manassas has used its property rights as owner to block the public (mostly non-city residents) from fishing or boating on the city's reservoir.

Lake Manassas Dam blocks Broad Run to create a drinking water reservoir

Lake Manassas is located in Prince William County, but owned by the City of Manassas

Source: Google Maps

Fairfax County did play hardball in those days, and acquired through eminent domain the water supply of Alexandria in the 1960's. Fairfax County could not seize property of a fellow local government to gain an advantage in negotiating annexation and other issues, but it could condemn the private Alexandria Water Company that had built the Occoquan Reservoir and was selling water to Alexandria. After paying fair market value as required by the Fifth Amendment, Fairfax County seized control of the reservoir and water system that even today supplies Alexandria and much of eastern Prince William County.

Today the corporate successor to the Alexandria Water Company, Virginia American Water, purchases drinking water wholesale from Fairfax Water and supplies customers within Alexandria. Rates charged to Alexandria customers are determined by the State Corporation Commission, based on the costs to provide the service plus a reasonable return on investment. City officials routinely object to rates proposed by the private utility, and lawyers dispute at the State Corporation Commission until the state agency makes a decision.16

Lake Barcroft supplied drinking water to Alexandria between 1915-1950, but is a recreational amenity now

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Political boundaries shape the development of water systems. Different raw water sources have been tapped to supply different jurisdictions in Northern Virginia, but topography shapes the development of the actual drinking water infrastructure. Water obviously flows by gravity, and even competing jurisdictions normally prefer to partner when building the water distribution system. The costs to build duplicate pumping stations/duplicate pipes in the same watershed is excessive; drinking water systems are natural monopolies.

The cities of Manassas and Manassas Park and the counties of Fairfax and Prince William have created an unusual water source - the wastewater treatment plant operated by the Uppper Occoquan Service Authority (UOSA). That 54-million gallon/day facility receives sewage from the four jurisdictions. The original source of the water that ended up as sewage in mostly from the Potomac River, pumped by Fairfax Water through the James J. Corbalis Jr. Water Treatment Plant near Herndon. Some of the source water comes from Lake Manassas, and was processed to drinking water standards by the City of Manassas.

The sewage is processed to a high level, then discharged into Bull Run near Route 28. The treated wastewate flows into the Occoquan Reservoir. Fairfax Water gets raw water from the reservoir and treats it to Safe Drinking Water Act standards at the Griffith Water Treatment Plant.

Most residents in eastern Fairfax and Prince William counties drink water coming from the Griffith Water Treatment Plant. The source water includes rain, stormwater washed naturally into the Occoquan Reservoir, and wastewater that the Uppper Occoquan Service Authority treated to a high level before discharge. Because the wastewater from the Uppper Occoquan Service Authority flows down Bull Run and into the reservoir before being treated, the system is not a direct toilet-to-tap process. Bull Run and Occoquan Reservoir serve as environmental buffers, and there is rarely any public objection to "drinking sewage."

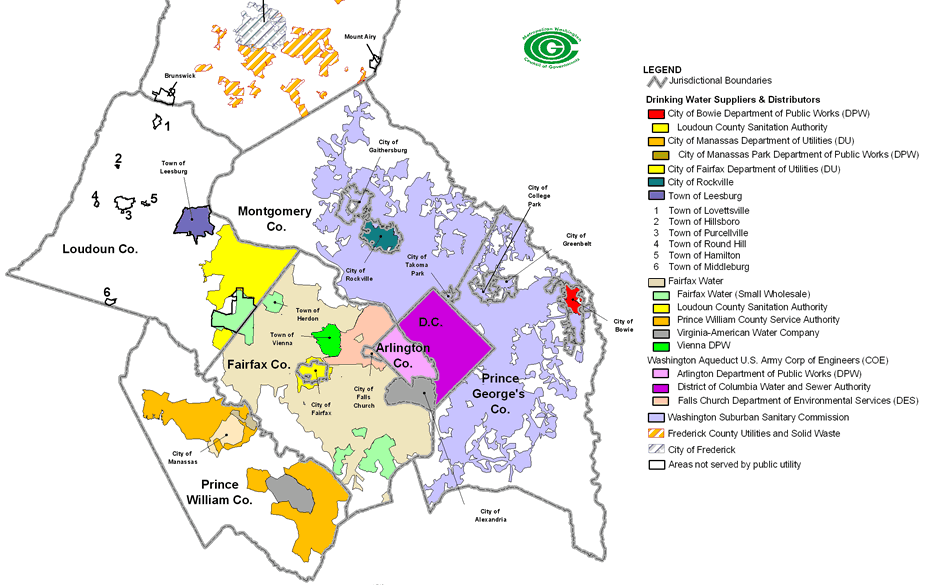

different utilities provide drinking water to different areas (Falls Church and City of Fairfax are now consolidated with Fairfax Water)

Source: Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, Service Areas for Washington Metropolitan Region Water Suppliers and Distributors

There are limits to jurisdictional cooperation dealing with water utilities. For decades the City of Falls Church bought drinking water from the County of Fairfax at wholesale rates, then charged customers a much higher retail rate. Many of those customers were not city residents, and profits from the city's utilities program enabled the City Council to set low property tax rates. Customers living in Fairfax County and buying high-priced City of Falls Church water were subsidizing government services for city residents.

The Fairfax County Water Authority (now Fairfax Water) decided to compete for the customers located within Fairfax County, breaking an informal understanding that separate jurisdictions would service different areas. The resulting "water war" between the jurisdictions led to multiple lawsuits. Ultimately, Fairfax Water acquired the drinking water systems of the City of Falls Church and also the City of Fairfax, creating a near-monopoly for supplying drinking water within the boundaries of Fairfax County.

All Northern Virginia cities and counties have linked their systems together now, and all have agreed on a water-sharing plan in times of scarcity. This cooperation was spurred in part by a severe drought in 1966, then another one in 1978 and a more-recent drought in 2002. The contrast of the relatively low flow at Goose Creek near Leesburg in 2002 with other years, as measured by USGS, is clear:17

| Water Year | 00060, Discharge, cubic feet per second |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 231.4 |

| 2002 | 80.0 |

| 2003 | 811.5 |

| 2004 | 526.5 |

| 2005 | 404.2 |

| 2006 | 248.0 |

| 2007 | 305.7 |

After a state-mandated water supply study following the 2002 drought, Fairfax Water was able to convince officials in the cities of Falls Church and Fairfax to abandon efforts to maintain separate drinking water systems, with independent capacity to survive future droughts. However, the independently-elected politicians in Loudoun, Prince William, and Fairfax counties did not decide to make a regional investment in new infrastructure, such as new dams and reservoirs, to supply the projected increase in population.

Instead, Loudoun and Fairfax counties both adopted the same long-term solution for a reliable supply of raw water - pump river water during periods of high flow into former rock quarries. The diabase rock is essentially watertight, which was demonstrated when Hurricane Agnes flooded a Loudoun County quarry in 1972. The water level stayed high until Luck Stone decided to pump the quarry dry and resume excavation of the rock.18

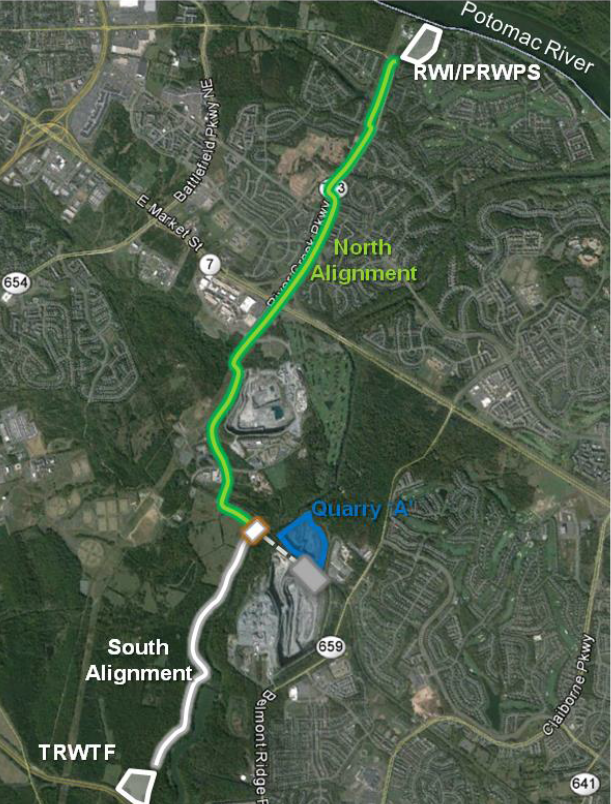

Loudoun will use Potomac River Water, storing it in the Luck Stone quarry where the Washington and Old Dominion Trail crosses Goose Creek. The first quarry (Quarry A) allowed storage of one billion gallons of water, but acquisition of additional quarries was planned to store eight billion gallons. Loudoun officials expected demand would increase from 68 million gallons of water a day in 2015 to 90 million gallons per day in 2040.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) issued Loudoun County a permit to withdraw water from the Potomac River on November 27, 2012. Maryland did not try to block the permit, having lost the legal battle with Fairfax Water a decade earlier.19

Loudoun then built a Potomac River Water Pumping Station, next to Leesburg's Kenneth B. Rollins Water Filtration Plant. It had the capacity to withdraw 40 million gallons per day from the river. A new six-mile pipeline linked the pumping station to the quarry and the Trap Rock Water Treatment Facility. Opening Trap Rock in 2019 increased capacity by 20 million gallons per day, allowing the county to close the Goose Creek facility producing 12 million gallon per day of drinking water.

In 2024, Leesburg closed down the Paxton well, its last well extracting groundwater as a source of drinking water. The Kenneth B. Rollins facility:20

Source: Loudoun Water, Potomac Water Supply Program Overview

Source: Loudoun Water, Trap Rock Water Treatment Facility

Loudoun Water built a raw water transmission pipeline from its Potomac River intake to the Trap Rock Water Treatment Facility

Source: Loudoun Water, Potomac Water Supply Program - March 2016 Update

Loudoun Water built an intake structure to transfer water from the Potomac River during periods of high flow to a quarry for storage in preparation for the next drought

Source: VA AWWA Plant Operations Committee, The Potomac Water Supply Program - Operational Considerations for the Intake, Ozonation, & Disinfection Systems

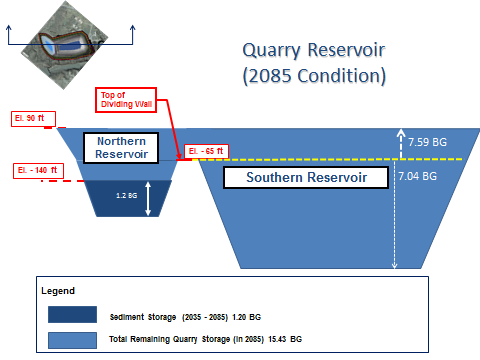

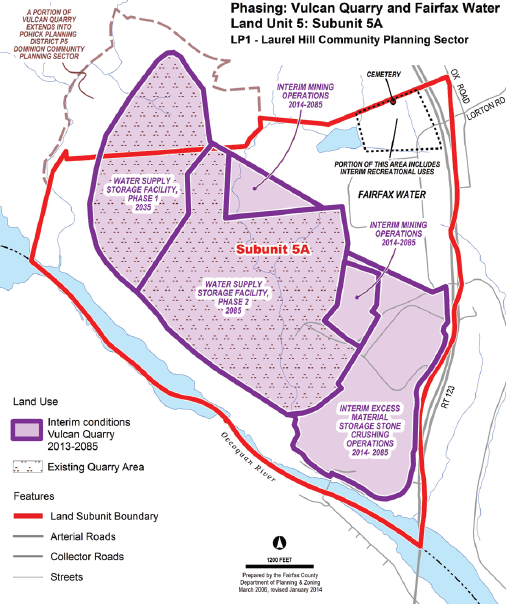

Fairfax Water planned to harvest "excess" Occoquan River water during periods of high flow, storing it in the Vulcan Materials Company quarry at Lorton. Fairfax will allow Vulcan to expand its quarry to remove rock from 150 acres owned by the county, and Vulcan will allow Fairfax to use an already-exhausted portion of its quarry to store 1.8 billion gallons by 2035.

Fairfax Water will utilize the Vulcan quarries at Occoquan as water reservoirs

Source: Historic Prince William, Old Quarry - #80

By 2085, Vulcan will have mined out the economically-recoverable rock. It will return the 150 acres to Fairfax and transfer its quarry too. Fairfax Water plans to store 15 billion gallons in the hole excavated for Vulcan's old quarry.21

Fairfax Water will expand its water storage capacity by converting the Vulcan quarry into a new reservoir by 2085

Source: Fairfax Water, Vulcan Quarry Water Supply Reservoir

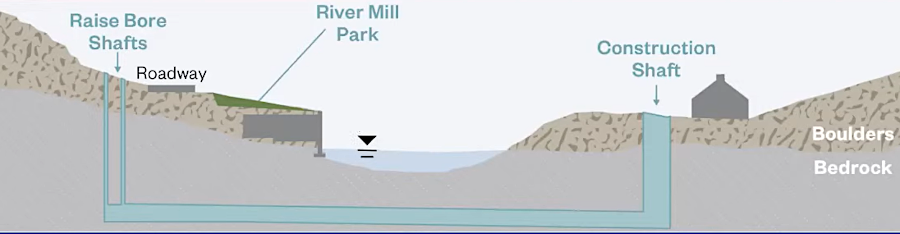

In the short run, Fairfax Water increased its capacity to pull water from the Occoquan Reservoir and distribute it to Prince William County. The utility announced in 2021 that it would install two new 42-inch pipes underneath the Occoquan River to the Griffith Water Treatment Plant in Lorton, drilling a tunnel beneath the river. New pipes would also handle higher pressure at connections between Fairfax Water and its wholesale customer, Prince William Water (which then resells to Virginia American Water).22

Fairfax Water expanded capacity to serve Prince William customers by drilling tunnels underneath the Occoquan River to install high-pressure pipes

Source: Fairfax Water, Occoquan River Crossing Virtual Public Meeting (March 23, 2021)

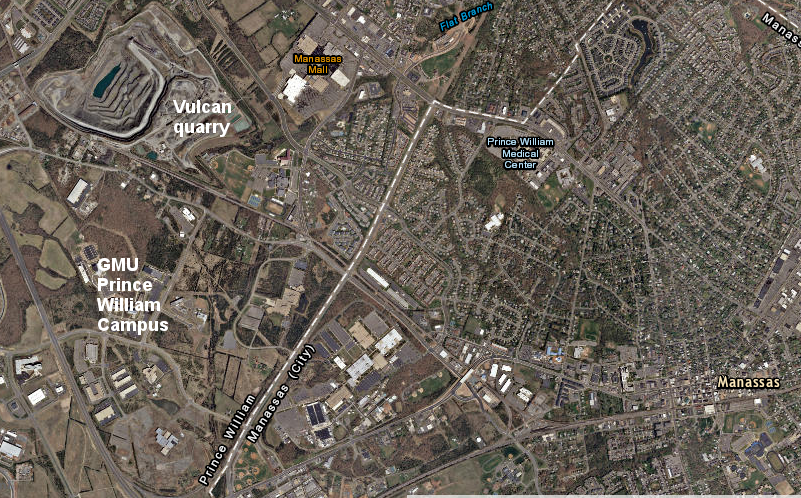

Prince William County or the City of Manassas could use a different quarry owned by Vulcan near Manassas Mall/Unity Reed High School to expand its water storage capacity. The city has sufficient storage in Lake Manassas to meet its projected needs, but the city also sells water to Prince William County. As population expands on the west end of the county, there will be an increasing need for additional drinking water.

Expanding Lake Manassas by raising the dam further would flood adjacent properties. Even if environmental impacts could be mitigated, that option is not economically feasible. The Vulcan quarry is five miles away from Lake Manassas, and the quarry is near the end of its economic life. There is still plenty of rock in the volcanic neck being excavated, but the cost of trucking rock from the bottom of the pit (which is already lower than sea level) is high.

A pipeline could be constructed to transfer water that distance during periods of high flows. The quarry was excavated in impervious diabase, so the rock walls would keep an artificial lake from leaking into the ground.

Manassas, like Loudoun and Fairfax, has the option of "banking" water in an exhausted rock quarry

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Creating artificial lakes that could be drained as needed during periods of low water flow. Off-stream storage reservoirs reduce impacts on fish, wildlife, wetlands, boating, and riparian landowners, and repurposing rock quarries allowed Loudoun and Fairfax counties to plan, finance, and manage their drinking water systems separately.

One theoretical solution to increasing water supply was to build a large reservoir. Alexandria Water and the Town of Fairfax built reservoirs blocking streams in the 1950's and the City of Manassas build a reservoir blocking a major stream in the 1960's, but environmental constraints are now a factor - and there are no longer any empty spaces where land could be flooded.

As recently as 1999, the League of Women Voters in Fairfax County had re-confirmed the problem with building new reservoirs far upstream in the Shenandoah and Potomac River watersheds, or a dam on the main stem of the Potomac River at Seneca Creek upstream of Great Falls:23

the Vulcan Quarry at Lorton will be repurposed as it is mined out, and by 2085 will become a new water storage reservoir for Fairfax Water

Source: Fairfax County, 2013 Comprehensive Plan - Lower Potomac Planning District (p.55)

The 2002 drought led to completion of the 2011 Northern Virginia Regional Water Supply Plan. That was updated in 2018. That revision incorporated changes in responsibilities among jurisdictions to provide drinking water, plus Loudoun Water's authorization in 2014 to withdraw 40 million gallons per day from the Potomac River.24

The scheduled 2023 "major update" of the water supply plan was delayed. One issue requiring resolution was defining the quantity of water that would be required by new data centers. In addition, there was a strong desire to diversify the source of water supply. The Potomac River was the source for 78% of the region's water. Arlington County and the District of Columbia were 100% dependent upon the river. The new water supply study explored finding secondary water sources to enhance resiliency and security.

The new study required cooperation of the various jurisdictions and regional drinking water utility systems, so the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments and the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin (ICPRB) were key partners.25

A 2024 study revealed that the District of Columbia would exhaust its supply of drinking water within 24-48 hours, if the sole source of the Potomac River was contaminated and the Washington Aqueduct was closed. The region got a taste of that threat in 2026.

The Potomac Interceptor sewer pipe broke and released 60 million gallons of untreated sewage daily. DC Water redirected the wastewater into a dry section of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal before pumping it back into the sewerline downstream of the break. The sewage, which came from as far away as Dulles International Airport, flowed ultimately to the Blue Plains treatment plant.

That event caused no impact on drinking water supplies because the break occured downstream from the water intakes for all the jurisdictions. No extra restrictions on water use had to be imposed, that time.

One option explored for future water storage was use of the Travilah Quarry in Rockville, Maryland as a new reservoir. However, the quarry would not become available to store water until the middle of the century. To diversify the source of drinking water, DC Water chose to reprocess Blue Plains facility wastewater to meet drinking water standards. The initiative started with construction of the Pure Water DC Discovery Center at Blue Plains in 2026.26

in 2024, 78% of the water in the DC region was supplied by the Potomac River

Source: Metropolitan Washington Council of Government (MWCOG), COG Board supports effort to improve regional water supply resiliency (September 28, 2022)

rain that falls on Bull Run Mountain at Thoroughfare Gap (Prince William County) emerges in a spring 100 feet lower in elevation

Fairfax Water wholesales treated drinking water to Loudoun Water, Prince William County's Service Authority, the Town of Vienna, and Virginia-American Water

Source: Fairfax Water, Occoquan River Crossing Public Meeting (March 24, 2021)

water supplier service areas (omitting City of Manassas) in 2025

Source: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin (ICPRB), 2025 Washington Metropolitan Area Water Supply Study (Figure 2-2)