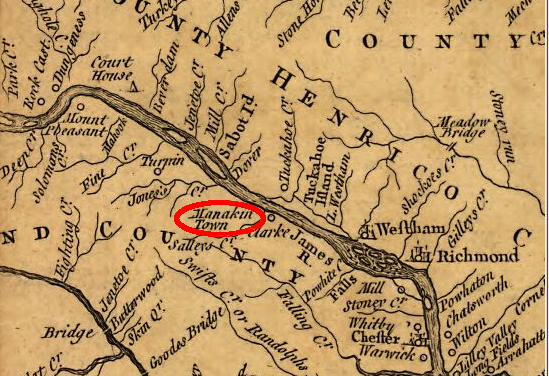

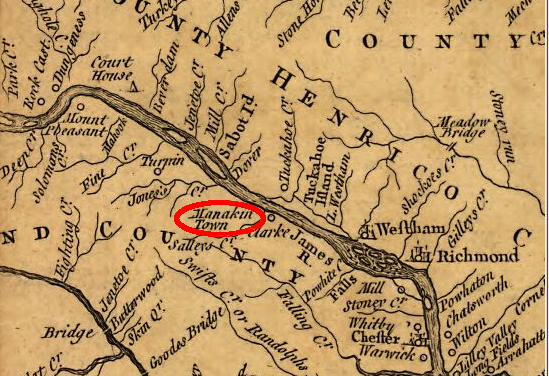

Manakin Town, upstream of Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1751)

Huguenots were Protestants living in France. While it was officially a Catholic country with a Catholic king, the Protestants were tolerated under the Edict of Nantes.

Louis XIV revoked that edict in 1685. Protestants in France were forced to convert and become Catholics or to flee to other countries that welcomed Protestants.

At the same time, English kings were struggling with their own choice of religion. Charles II was ostensibly a Protestant, but when he died in 1685 his brother and successor, James II, was overtly Catholic. Parliament was dominated by Protestants throughout this time. In 1688, James II was ousted in the "Glorious Revolution" and replaced by a clearly-Protestant William and Mary.

In England, the French Protestants were welcomed as temporary refugees, with the expectation that they were waiting until the policies in France changed again. In the New World, however, the colonies tried to recruit the Huguenots as permanent settlers. Virginia was land-rich and people-poor, and Protestant refugees were prime targets for expanding the local population.

One Huguenot traveler in Virginia arrived after 19 rough weeks of sailing. Durand de Dauphine finally passed New Point Comfort and arrived at the North River separating Mathews and Gloucester counties on September 22, 1686.

Durand de Dauphine had fled France rather than recant and profess to being a Catholic. After reaching England, he determined that he preferred taking a chance and examine Charleston in the southern half of the Carolina colony, rather than live in exile in the big city of London.

While in France, he had already read propaganda from Carolina advertising why it was a good place for settlers. He knew he was not the first to prefer Carolina over Virginia:1

Durand de Dauphine also knew that the climate was different from France:2

Still, the idea of settling in Virginia was attractive to the French refugee:3

Durand de Dauphine had accumulated capital in France and managed to escape with some money. He could have afforded to pay for the passage of an indentured servant, entitling him to 50 acres of land, or to purchase land and slaves to work it. He considered the English to be lazy, noting that clothes were imported rather than woven in Virginia, where "not one woman in the whole country knows how to spin."4.

He also considered it wasteful for Virginia farmers to plant without plowing, when the coastal soils were so free of stones. Durand de Dauphine calculated that French Huguenots, accustomed to working hard to pay Louis XIV's heavy taxes, would thrive in Virginia:5

The Virginia Governor, Francis Howard of Effingham, and William Fitzhugh both tried to convince Durand de Dauphine to return to Europe and lead fellow Huguenots back to Virginia. Governor Howard promised to enlarge the standard 50 acre/person land grant for those who paid their own passage across the Atlantic to 500 acres for Durand de Dauphine.

The Governor also promised that the French Protestants could have their own ministers rather than be required to attend Anglican services:6

The enticements failed to convince Durand de Dauphine. He recognized that the land being offered would be easy to farm, but hard to make profitable because of transportation costs:7

Another unsuccessful recruiter of Huguenots was Nicholas Hayward. He purchased a large tract from Lord Culpeper in 1687, but that land was valueless unless Hayward could get settlers to purchase it or pay him rent.

His brother Samuel Hayward formed a company with two other London speculators, Richard Foote and Robert Bristow, plus a local Virginian George Brent. Together they planned to establish Brent Town/Brenton and populate it with French-speaking Protestants. A surge of Huguenot refugees fled to England in 1687 after King James II issued his Declaration of Indulgence.

These refugees came with an unusual set of skills:8

Durand de Dauphine noted, while visiting William Fitzhugh at his Bedford estate east of modern-day Fredericksburg:9

Fitzhugh also desired to settle Huguenots on his lands, but the Northern Virginians were unable to recruit enough French-speaking "early adopters" to make their area a desirable location for less-adventurous settlers.

Both North Carolina and Virginia landowners sought to recruit boatloads, literally, of Huguenots. At the end of the 17th Century, King William III rejected the proposal of William Byrd I to establish a new community near Richmond, and instead authorized Huguenot refugee settlement near Norfolk on lands owned by court physician Daniel Coxe.

When the French Huguenots reached Virginia in 1700, Byrd's influence was demonstrated by the decision of Lieutenant Governor Francis Nicholson to ignore the royal guidance. Governor Nicholson directed the French-speaking immigrants to settle above the Fall Line at the former Monacan town of Mowhemencho, on a grant of 10,000 acres.

Manakin Town, upstream of Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1751)

Nicholson cited the confusion regarding the Virginia-North Carolina border as one reason for ignoring the king's direction, but clearly William Byrd I benefitted from the decision to ignore the king's orders. Chesapeake Bay was the point of entry for immigrants, and Virginia officials took advantage of it to ensure immigrants stayed in Virginia rather than ended up in North Carolina.

Lieutenant Governor Nicholson, like Governor Spotswood later, saw immigrants as a potential buffer to be placed between existing colonial settlements and the threatening Native Americans on the western frontier. The Huguenots arriving in 1700 had expected to settle near the Atlantic Ocean, where they could manufacture cloth and other trading goods. Instead, the immigrants ended up being dispatched to new lands beyond existing English settlements and forced to earn a living as farmers:10

Huguenot Bridge over James River, upstream of Richmond and downstream from Manakin-Sabot

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Huguenot Bridge reconstruction (photo by Trevor Wrayton, VDOT)

Frantz Ludwig Michel arrived in 1702, seeking a place to settle 400-500 people. They were Anabaptists from Bern, and the Swiss canton was anxious to deport the religious dissidents. For the next five years, Michel looked for opportunities to get free land and other subsidies from English official in London and colonial officials in Williamsburg while still charging Bern officials for taking the Anabaptists away.

Michel examined Manakin and met with other Huguenots living on the Mataponi River in 1702. After he decided those places were not suitable, he became particularly interested in land near the mouth of the Shenandoah River. Michel is the first European to document his travels there in 1707, and to produce a map of the Shenandoah Valley.11

In 1709, many Huguenots and other Protestants fled from the continent to London.