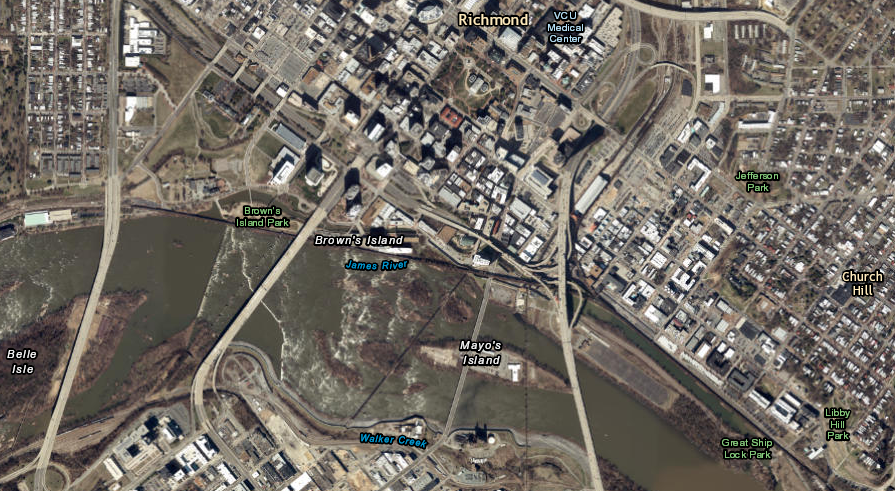

Richmond developed as a port because rapids at the Fall Line blocked ships from moving further upstream

Source: Google Maps

Richmond developed as a port because rapids at the Fall Line blocked ships from moving further upstream

Source: Google Maps

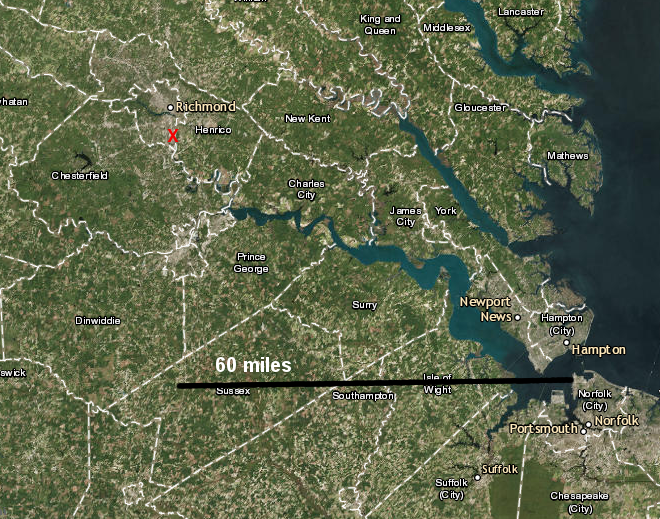

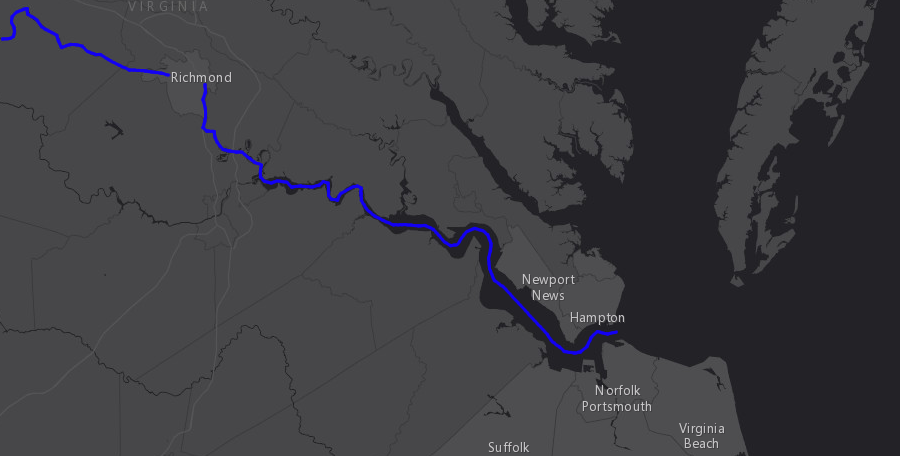

Richmond is a port city, located 60 miles inland from Norfolk. Because the James River winds back and forth, ships must travel nearly 100 miles upstream by water to reach Richmond's wharf.

The city claims to have the "westernmost commercial maritime port on the North Atlantic coast" with "the quickest access of any port to I-95." Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT), managed by the Virginia Port Authority, is located "westward as far as deep water will allow."1

Since the 1870's, Richmond has lost its competitive advantage over sites in Hampton Roads with deeper shipping channels. The terminal at the Port of Richmond is inaccessible to ocean-going container ships today, because the 25-foot deep shipping channel in the James River is too shallow. As noted by a Port of Virginia spokesperson:2

the Port of Richmond is 60 miles west of Norfolk, putting it closer to I-95 and major markets

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

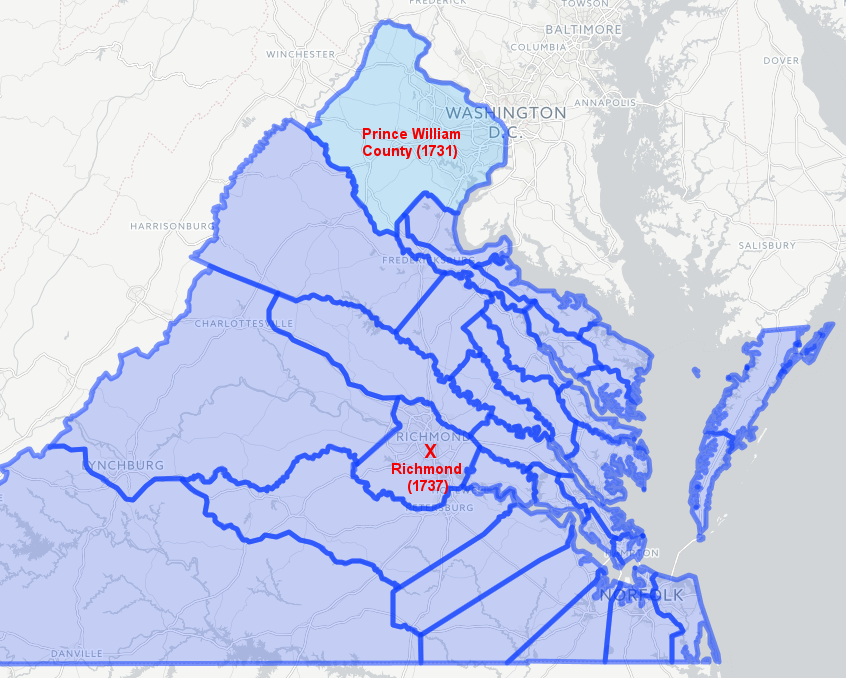

It took over 125 years before the English colonists who had landed at Jamestown developed a port at Richmond. The first colonists explored up to the Fall Line of the James River in 1607 and were familiar with the site, but chose to create their first settlement closer to the Atlantic Ocean. As the population expanded, new settlements were started upstream. Colonization did not advance beyond the mouth of the Appomattox River before the 1622 uprising led by Opechancanough.

For the next century, English settlement focused on the more-accessible locations along the shorelines of Tidewater rivers. Even Prince William County, stretching up the Potomac River to the Fall Line, was chartered six years before Richmond was founded in 1737.

there were enough settlers on the Potomac River to justify creation of Prince William County before Richmond was chartered

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

William Byrd II chose the Fall Line of the James and Appomattox rivers as sites for the future cities of Richmond and Petersburg. Byrd recognized clearly that the physical limitations to upriver travel caused by the Fall Line would trigger development of towns at those sites once population increased:3

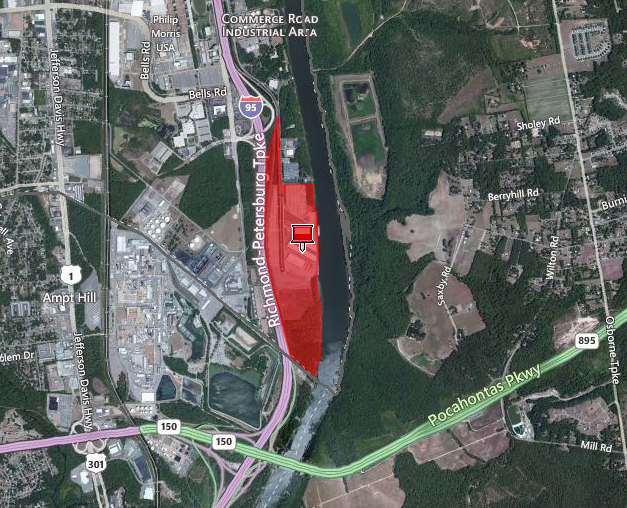

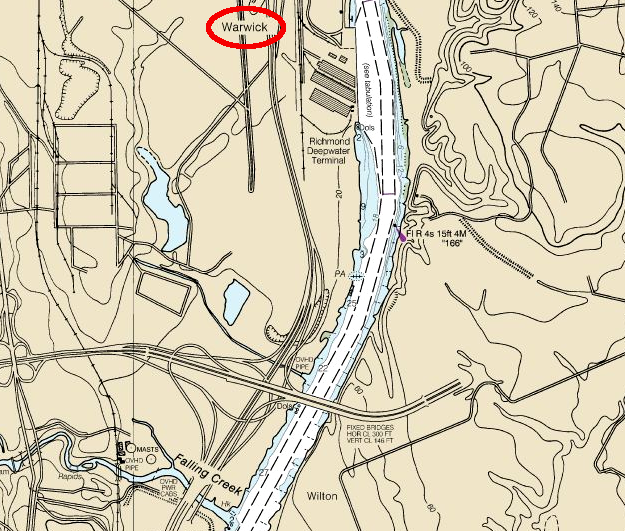

The main wharf for ocean-going ships was five miles downstream of the Fall Line, at a site known as Warwick near the mouth of Falling Creek. A shallow sandbar there limited navigability during colonial times.

the modern Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT) is at Warwick, where a shallow sandbar used to force ships sailing to Richmond to load/unload

Source: City of Richmond, Richmond Parcel Mapper

Warwick and its "ropewalk," used for twisting hemp fibers to make rope for the Virginia Navy, was destroyed by Benedict Arnold on April 30, 1781. The modern Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT) occupies some of that site.4

the US Army Corps of Engineers maintains a 25-foot deep channel to the Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, James River Jordan Point to Richmond (NOAA Nautical Chart 12252)

Richmond became the capital of Virginia in 1780. Prior to Benedict Arnold's raid in 1781, grist mills were built there to grind corn and wheat into flour. The availability of waterpower and transportation downstream to markets in the northern states, Caribbean, and Europe made clear that Richmond would develop into a manufacturing center producing goods for shipment. Shipping also would increase as products from upriver were warehoused at the Fall Line and then transferred into ocean-going ships, and as population growth increased the demand for imported goods.

Richmond grew because it was located at the Fall Line of the largest watershed in the state, the James River. Dugout canoes and then bateaux carried cargo down to Westham and sometimes through the rapids to Shockoe Creek. Wagons carried some agricultural products directly to Richmond warehouses from the Piedmont farms. Starting in the 1730's, wagons and then Virginia's first railroad carried coal from mines in Henrico and Chesterfield counties to the James River. There it was loaded onto ships for transport to Philadelphia, New York, Charleston, and Savannah.5

At the end of 1789, the James River Canal was completed to Westham, seven miles above the rapids. The canal allowed small boats to bring cargo around the Fall Line to the ocean-going ships that could sail up the James River to the mouth of Shockoe Creek.6

Streets in downtown Richmond stayed busy with wagons moving cargo to those warehouses, and then from warehouses to larger boats that could sail up the James River to the rapids. As predicted by William Byrd, Richmond became a site "where the traffic of the outer inhabitants must centre." In 1800, the city became a customs port for collection of import duties.7

Increased wheat farming in the Piedmont and construction of the James River and Kanawha Canal beyond the Blue Ridge led to a Richmond emerging as a major exporter of flour, as well as tobacco. Some wheat arrived already milled near the farms and was known as "canal flour," while wheat ground at mills in the city produced what was perceived as higher-quality flour.

Joseph Gallego started his milling operations around 1800, the Haxall family joined the industry a decade later, and multiple other competitors made Richmond a major source of exported flour. Water diverted from the James River and from the transportation canal was used to power most of the mills.8

After the American Revolution, trade with northern ports grew, replacing the more-expensive imports from England and the rest of Europe. The first ship powered by a steam engine arrived in Richmond in 1815, and the steamboat "Powhatan" began regular service in 1816. Reliable propulsion meant a steamboat could schedule stops at Baltimore, Norfolk and Richmond each week.9

Shipping traffic increased after the War of 1812 ended. The new technology of steam engines made water transport increasingly cost-effective, compared to the alternative of wagon transport on dirt roads that turned to mud whenever it rained.

Thanks to ships steaming all the way up the James River to the Fall Line, Richmond's shipping business surpassed Norfolk and Portsmouth. Richmond became Virginia's dominant port in the 1820's, and kept that lead for the next 50 years.10

Construction of the James River and Kanawha Canal steered towards Richmond the trade in agricultural products from the Piedmont and west of the Blue Ridge. Railroads provided a faster and less-expensive way to ship goods from the Piedmont to the Fall Line in the 1840's. "Internal improvements" increased Richmond's central role in the James River watershed.

Completion of the Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad to Weldon, North Carolina in 1837 could have siphoned off much of the traffic coming from the Roanoke River watershed. Business and political leaders in Richmond and Petersburg feared they would be bypassed, once the railroad made it easy and cheap to send cargoes directly to a Chesapeake Bay port.

Competition between the Fall Line port cities and the Hampton Roads port cities was intense. In 1844, Petersburg even sent workers to physically destroy a portion of the Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad, and kept it closed for two years.

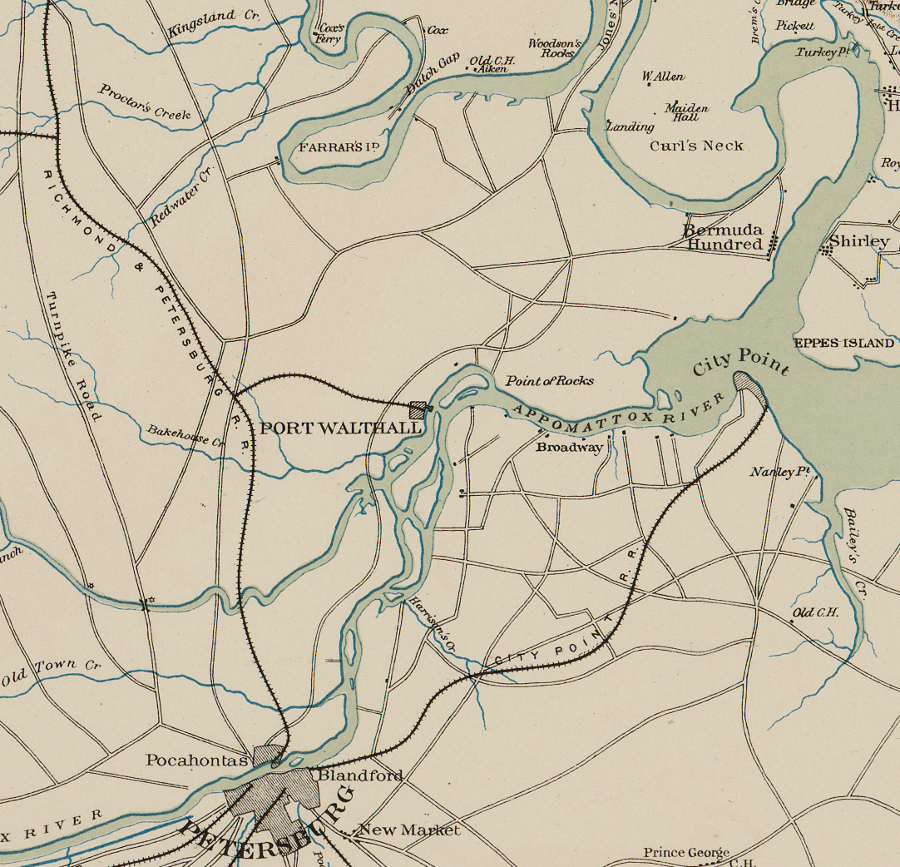

Once that rival shipping route was disrupted, Richmond then undercut Petersburg's trade. It built one rail line south to the deep channel at Port Walthall near the mouth of the Appomattox River, and another east to the deep channel at West Point on the York River.11

prior to the Civil War, both Richmond and Petersburg built railroads to wharves near the mouth of the Appomattox River

Source: US War Department, Atlas to accompany the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Southeastern Virginia and Fort Monroe Showing the Approaches to Richmond and Petersburg (1862)

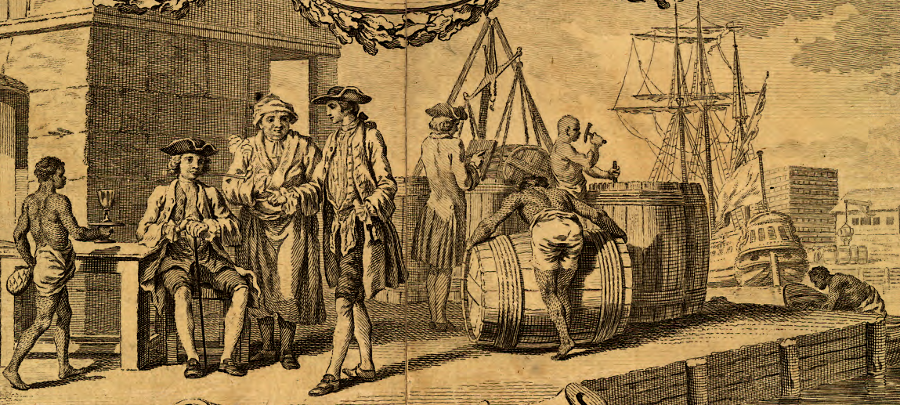

Enslaved people using their muscles loaded and unloaded most cargo. They were assisted by block and tackle equipment, powered at times by horses. Richmond shipped out agricultural goods, lumber, and iron, while importing manufactured goods and guano to fertilize exhausted tobacco fields. Shockoe Creek developed into an open sewer, carrying most of Richmond's stormwater and human/animal waste directly into the James River where the ships were concentrated.12

many of the first teamsters and longshoremen, transporting hogsheads of tobacco at colonial Virginia wharves, were not paid any wages for their labor

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

After the American Revolution, Virginia began to produce more enslaved children than slaveowners could use effectively. In 1808, the United States banned the import of slaves, and Virginia planters such as Thomas Jefferson treated their slaves as a "crop" to be raised and sold. The state began to export large numbers of surplus slaves to new agricultural areas in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

The slave markets in Richmond, which were concentrated around 15th Street near today's Main Street Station, exported their "product" from the Manchester Docks. Slaves were marched from their holding centers in the valley of Shockoe Creek, such as Lumpkin's Jail, to the south side of the James River. After crossing Mayo's (now 14th Street) Bridge, they walked to what is known today as Ancarrow's Landing at the southern end of the Richmond Slave Trail. An underwater granite ledge, once known as Jones Rock, limited the ability of ocean-going ships to sail upstream.13

in the 1800's prior to the Civil War, slaves were forced to walk across the Mayo Bridge to the Manchester Docks and shipped as "cargo" to markets further south

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Between 1816-1819, the Richmond Dock Company created new facilities just downstream from Shockoe Creek. It built embankments that extended Chapel Island parallel to the northern bank of the James River.

In the process, the Richmond Dock Company enclosed the portion of the James River reserved for general public use and known as the Commons. Chapel Island had been a sometimes-underwater sandbar also known as the Sandy Bar Fishery, due to the shad and other fish that could be caught in the river there. There was an Anglican chapel on Chapel Island, and it was replaced by construction of St. John's Church on Church Hill.

The enclosed portion of the James River between 14th Street and 28th Streets became the Richmond Dock. It was a protected pond with a consistent water level, which was known in England then as a "dock." The dock eliminated the up-and-down motion caused by the tides, since the lock at the southern tip controlled water levels. Today, it is part of Great Shiplock Park.

Five acres at the site of Richmond's first port, just downstream of the lock, was protected from development in 2021 and incorporated into the park. There was still a 350-foot wharf on the property, reflecting its shipping heritage.

five acres between Dock Street and the waterfront, at the site of early port facilities, was added to Great Shiplock Park in 2021

Source: City of Richmond, Richmond Parcel Mapper

Slaves provided most of the manual labor for loading/unloading cargo, while horses and wagons carried ("drayed") goods back and forth from the warehouses that lined the northern bank.

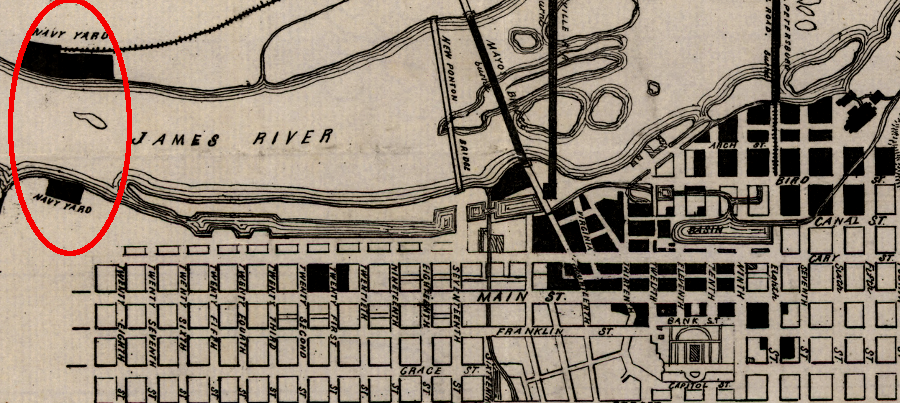

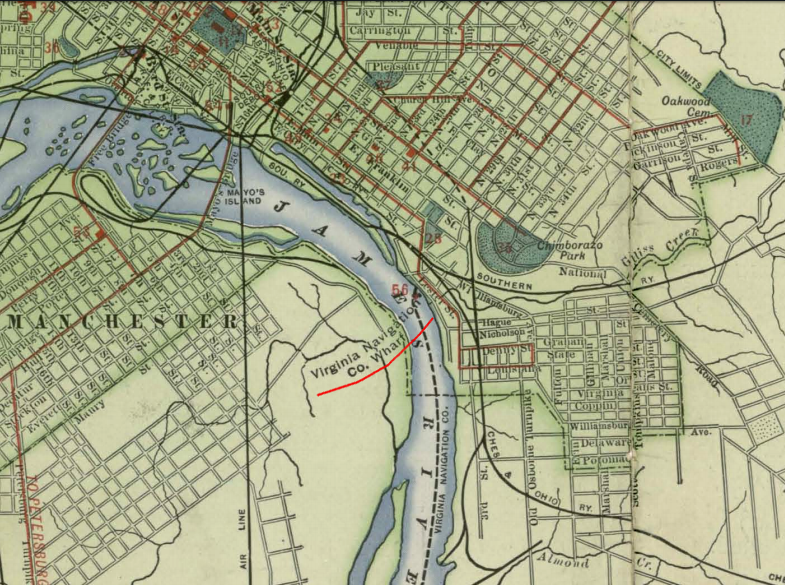

the Richmond Dock (north of red line) allowed more ships to transfer cargo closer to Richmond, upstream of Rocketts Landing

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Richmond, Virginia (1864)

In 1854, the northern end of the Richmond Dock was connected to the turning basin of the James River and Kanawha Canal between 8th and 11th streets. The new locks of the "Tidewater Connection" finally enabled canal boats to reach the James River, and reduced the need to cart goods by horse and wagon from the canal to warehouses further downstream.

the James River and Kanawha Canal was extended from the canal basin via the Tidewater Connection (above red line) to the Richmond Dock, streamlining the transfer from canal boats to ocean-going vessels of tobacco, flour, iron, coal, wood products, and other items to be shipped to other distant ports

Source: David Rumsey Map Collection, Gray's New Map of Richmond, Henrico County, Virginia (by O. W Gray, 1884)

After the link was built, a canal boat could be pushed by poles and hauled by mules all the way from the town of Buchanan (west of the Blue Ridge) east into the tidal portion of the James River, and then on to Rocketts Landing. Ocean-going ships that sailed to other ports on the Atlantic Ocean coastline, the Caribbean, South America, and Europe could be loaded from warehouses at Rocketts Landing.14

canal boats could enter the James River at what is now Great Ship Lock Park and travel further downstream to deeper water, where they would transfer goods to ocean-going vessels

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

On the southern end of the Richmond Dock, the old wooden lock built in 1819 was replaced with a stone lock. Those stones remains today in Great Shiplock Park.

Great Shiplock Park is located at the downstream end of Chapel Island

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Chapel Island is now used primarily to store stormwater runoff/untreated sewage waste in the Shockoe Retention Basin, part of Richmond's Combined Sewer Overflow project, but the southern end is open to the public at Great Ship Lock park

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Prior to the Civil War, Richmond was served by five different railroads. The last to be constructed was the Richmond and York River Railroad, which started operations in 1861. Its western terminal was near Rocketts Landing, and is now incorporated in the Fulton Yard of the CSX Railroad.

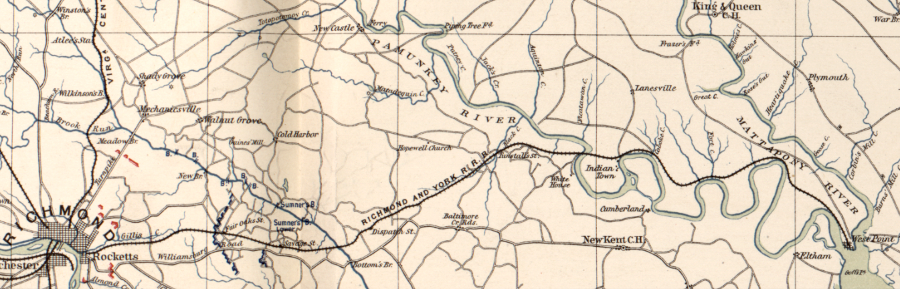

The eastern terminal was at the new town of West Point, where the York River offered a deeper channel. The Richmond and York River Railroad was a stand-alone operation when it began service in 1861, but after the Civil War it connected on its western end to the Richmond and Danville Railroad. The connection to a deep-water port at West Point helped the Richmond and Danville Railroad become a major route for shipping cotton.15

the Richmond and York River Railroad started operations in 1861 with no connection to another railroad in Richmond, but after the Civil War it was linked to the Richmond and Danville Railroad and became a major route for shipping cotton to the deeper-water port at West Point

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Richmond, Virginia

the Richmond and York River Railroad crossed the Pamunkey River and cut through the Pamunkey Reservation to reach West Point, where the York River begins

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of the War of the Rebellion, White House to Harrison's Landing; Yorktown; Williamsburg; Mulberry Island, Va

On the night of April 2, 1865, retreating Confederates set fire to warehouses on the Richmond waterfront. The Evacuation Fire spread out of control and burned much of Richmond's commercial district, including the multi-story flour mills that generated much of the pre-war shipping from Richmond. The stone locks of the Richmond Dock Company, James River and Kanawha Canal, and the Tidewater Connection survived the fire intact.

when the Confederates evacuated Richmond on the night of April 3, 1865, they burnt the navy yards at Rocketts and Manchester on purpose - and much of the commercial waterfront by accident

Source: Library of Congress, Map of a part of the city of Richmond showing the burnt districts

the burning of Richmond in 1865 destroyed primarily infrastructure involving river-related industry, storage, and transportation

Source: Library of Congress, The fall of Richmond, Va. on the night of April 2d. 1865

Union forces moved the debris from the scuttled fleet of the James River shipping channel soon after the end of the Civil War. Reopening the river channel enabled delivery of supplies to the occupying Union Army. From a civilian perspective, clearing the channel facilitated the economic recovery of Virginia's capital city.

Union steamships and sailing vessels were the first ships to bring supplies to Rocketts Landing after the Confederates evacuated Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, View on the docks at Rocketts, Richmond, Va., April, 1865

Business at Richmond's port had surpassed Norfolk in the 1820's thanks to the new technology of the steamship, but changing technology after the Civil War cost Richmond its #1 status. The natural depth of the James River channel leading to Richmond was only 7-10 feet, but in the 1870's ever-larger ships required a deeper shipping channel.

In 1870, the US Congress re-admitted Virginia as a state and appropriated funds to clear obstructions in the James River. The city also provided some funding. The James River shipping channel was reopened by removing the sunken ships used to prevent the Union Navy from steaming past Drewry's Bluff. The Dutch Gap Canal was

The port of Richmond was handicapped by the shallow channel and the length of time required for ships to steam upriver to the Fall Line. Deep-water ports were available naturally at Hampton Roads, while it was expensive to excavate an artificial channel in the sediments of the James River to make Richmond equally accessible to the larger post-war ships.

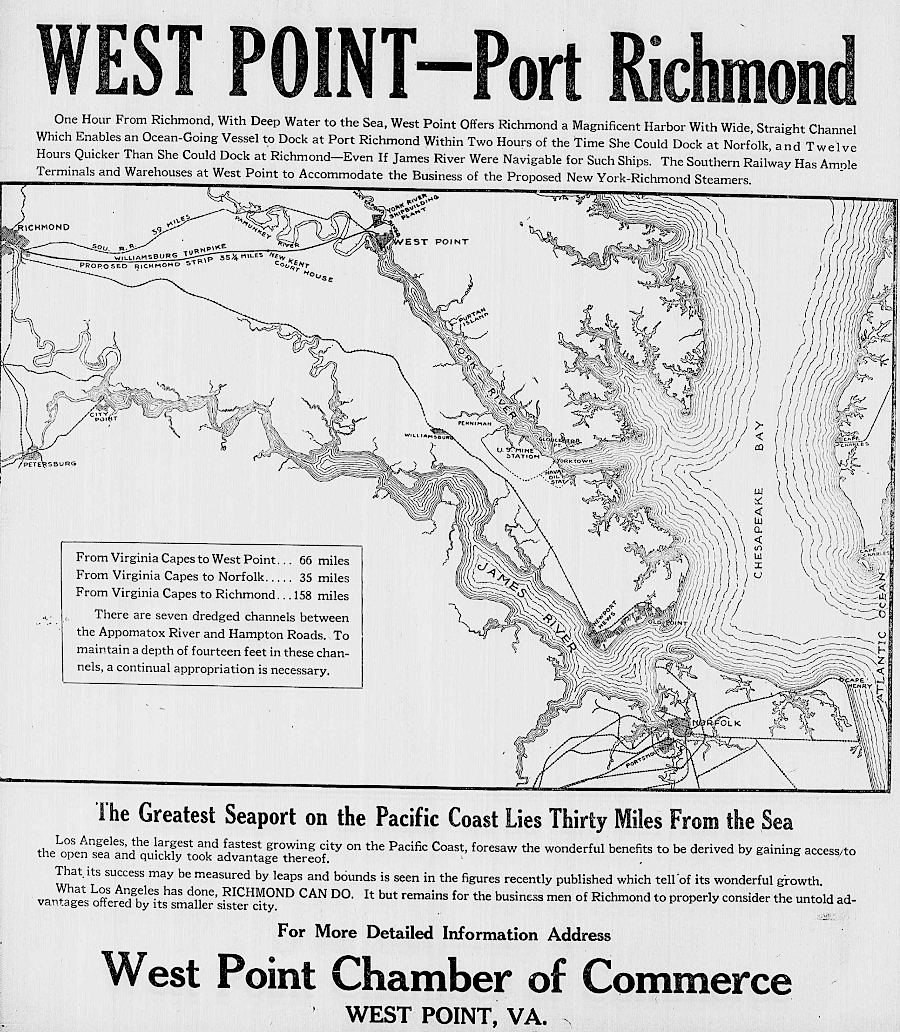

The need for access to deeper water had been recognized prior to the Civil War. The Richmond and York River Railroad built almost 40 miles of track east to West Point at the confluence of the Mattaponi and Pamunkey rivers, where the natural channel was over 18 feet deep. Railroad operations started in March, 1861, diverting ships from the port at Richmond but still bringing passengers and cargo through the city. Thanks to the Richmond and York River Railroad connection, Richmond became an "inland port."

the Richmond and York River Railroad, completed just before the Civil War, gave Richmond access to a deeper-water port on the York River

Source: Library of Congress, Lloyd's official map of the state of Virginia from actual surveys by order of the Executive 1828 & 1859

After the Civil War, the Richmond and York River Railroad was incorporated into a network of southern railroads controlled by the Richmond and West Point Terminal and Warehouse Company, the "Richmond Terminal Company." That holding company routed trains so West Point, rather than Richmond, developed into a major port for exporting cotton and for steamboat passengers traveling to Baltimore.

in 1920, West Point business leaders still sought to attract shipping to the port at the head of the York River

Source: Library of Congress, Chronicling America, Richmond Times-Dispatch, June 27, 1920 (Image 46)

Shipping traffic up the James River to Richmond stagnated in the 1870's and 1880's. Fewer ships could navigate the shallow channel, so shippers chose to use the deepwater ports at West Point and in Hampton Roads.

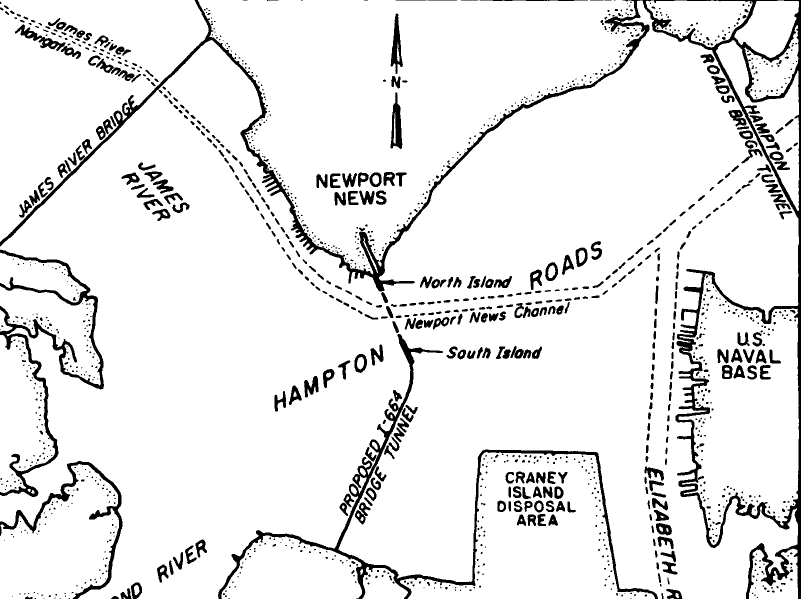

In 1882 the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railroad chose to create a new coal-exporting port at Newport News, rather than expand its facilities at Richmond. The railroad built new track past Richmond, bypassing the shallow stretch of the James River in order to get as close as possible to the Chesapeake Bay. The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built its terminal and started the new city of Newport News because the deep water sites at West Point, Portsmouth, and Norfolk were already occupied by rival railroads.

Richmond officials still sought to maintain shipping traffic to their dock, recognizing that warehousing, transportation, and manufacturing jobs would be concentrated at whatever site was the "end of the line" for trains and ships. The US Congress authorized dredging a 25' deep channel to Richmond in the River and Harbor Act of July 5, 1884, but funding was not provided to create the channel.

By the 1890's, the Richmond Dock was no longer essential for trade. Rocketts Landing could handle all the commercial vessels coming to Richmond.16

the 25' deep channel to Richmond was authorized in 1884 - but not completed until 1940

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

The Richmond Terminal Company trains continued past Richmond to West Point until 1895. After collapse of the Richmond Terminal Company and creation of the Southern Railroad as its successor in 1894, the new railroad developed a new terminal at Pinners Point on the Elizabeth River in Portsmouth and redirected rail shipments to that destination rather than West Point. What is now the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT), operated by the Virginia Port Authority, offered deeper water than Richmond and a quicker turn-around time for ships.

In 1899, after the Spanish-American War, the under-utilized Richmond Dock was converted into the Trigg Shipyard. It built warships for the US Navy and commercial shipping vessels; President William McKinley came for the launch of the first torpedo boat in 1899. The Trigg shipyard completed over 20 vessels, but the business lasted just five years and ended when William R. Trigg died.17

the William R. Trigg Shipbuilding Co. used the protected water in the Richmond Dock to construct destroyers and torpedo boats for the US Navy between 1898-1902

Source: Richmond Regional Planning District Commission, Chapel Island/James River Public Access Enhancement Project (p.3)

By 1916 the James River channel had been excavated to 18 feet deep. The city established the Richmond Port Commission in 1924 and the business community consistently advocated for Federal and state funding for navigation improvements.18

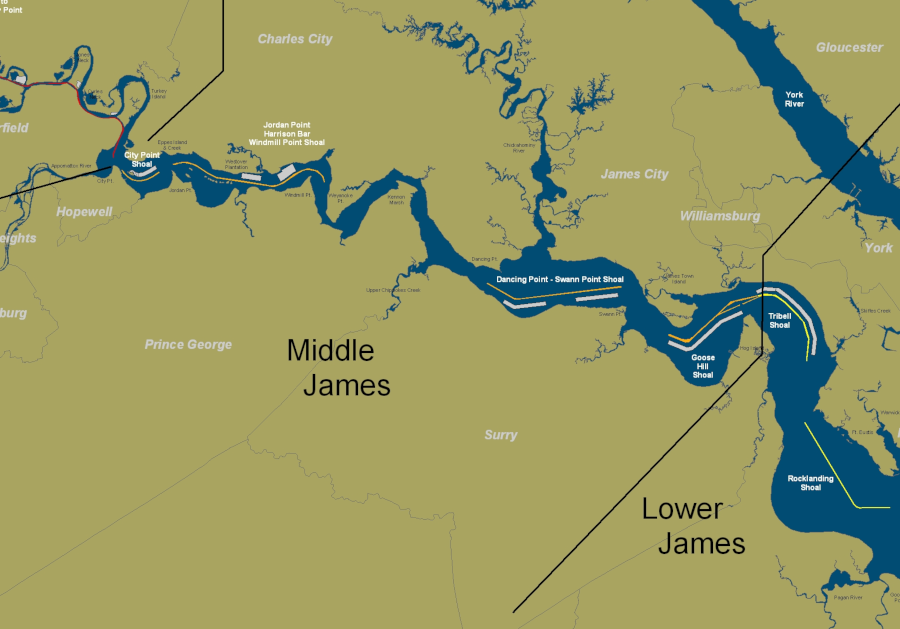

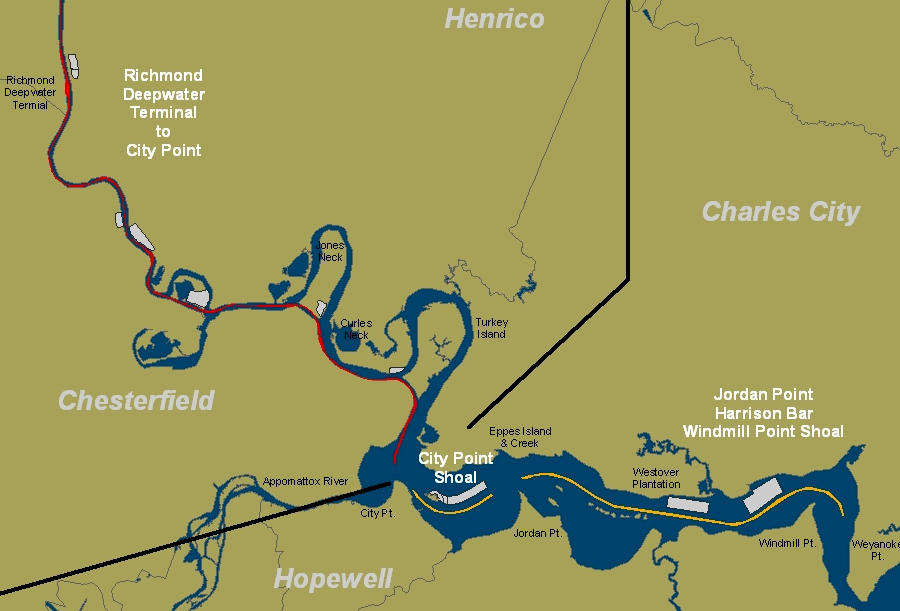

the US Army Corps of Engineers has straightened the James River with three artificial cuts through bends of the river

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, James River Navigation Channel Map

Between 1930-1940 the channel was deepened to 25 feet. Deepwater Terminal, four miles downstream of Richmond, opened in 1940 after the dredging was completed. Solid bedrock limited the ability to dredge the channel further upstream. For ships able to travel further upstream, the city developed Intermediate Terminal. It was at the site of the old Rocketts Landing. The "intermediate" indicated it was located between the Great Ship Lock (upstream) and Deepwater Terminal (downstream).

the Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT) is in the industrialized area of South Richmond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

At Intermediate Terminal, cylindrical towers built by Lehigh Cement dominated the waterfront. Large concrete warehouses built in the 1930's stored sugar imported from Cuba and tobacco imported for manufacturing cigarettes. Ships went downstream carrying tobacco, paper, wood products, and scrap iron.19

The delay in deepening the James River shipping channel constrained traffic to Richmond and spurred the growth of competing ports in Hampton Roads. Ships at Richmond could be only partially loaded with cargo, so less-than-full ships could navigate down the shallow river. Ships arriving with cargo for Richmond would unload in Norfolk, Portsmouth, Newport News, or City Point and the Richmond-bound cargo would be reloaded onto a smaller ship and "lightered" the rest of the way upstream.

the site of the Virginia Navigation Company steamship wharf was later renamed Intermediate Terminal

Source: Library of Congress, Trolley Rides in City and Country (1907)

Costs to ship goods to or from Richmond increased, because a second stop in Hampton Roads was required to add the rest of the load. As a result, fewer ships carried less cargo all the way upriver. In 1913, Congress reclassified Richmond as just a subport under Norfolk. Richmond continued to grow economically, but relied upon the railroads to offer a freight transportation alternative to shipping via the James River:20

after the Civil War, the US Army Corps of Engineers cut through three bends of the James River to make it easier/faster for long ships to get to Richmond - but ships expanded faster than the channel was improved

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the country between Richmond and Petersburg (1864)

ocean-going ships docked at Richmond's Intermediate Terminal just below the Fall Line in the 1950's

Source: Library of Virginia, Harbor (November 26, 1956)

Intermediate Terminal could be flooded by the James River

Source: Library of Virginia, High water, dock area (August 19, 1955)

Today the shipping channel to Richmond is still 25 feet deep, unchanged since 1940 despite efforts to get Federal funding to deepen the channel to 35 feet. Regular dredging keeps a 300' wide channel to Hopewell, and a 200' wide channel upstream to Richmond.

After World War II, gasoline and oil barges made regular visits to Richmond, but the US Congress had higher priorities than deepening the channel to reducing the costs of the light amount of traffic on the James River. The Norfolk District of the US Army Corps of Engineers maintains the 90-mile long channel at the 25 foot depth. The channel is 300 feet wide between Hampton Roads and Hopewell, and 200 feet wide from Hopewell to Deepwater Terminal.21

With the loss of low-cost transport, warehouses and factories moved away from the Richmond waterfront. At the base of Church Hill, the warehouses downstream from Intermediate Terminal have been converted into the Rocketts Landing development. The Virginia Capital Trail brings bicyclists and other recreational users to the former industrial waterfront, as does the Pulse Rapid Transit line. The only commercial shipping traffic is the Annabel Lee Riverboat, which docks at a wharf just upstream from Rocketts Landing.

the last commercial shipping to dock regularly at Rocketts (now converted into a residential development) is the Annabel Lee riverboat

The city ultimately decided to transform the Intermediate Terminal area into a waterfront park, and to finance construction of a restaurant associated with Stone Brewery in Fulton. Only one 32,000-square-foot warehouse remains at Intermediate Terminal, plus a massive concrete floor known locally as the "Sugar Pad." That pad is a remnant of the Warehouse #3 where Hershey stored sugar imported from Cuba, until that trade was blocked after Castro's rise to power in 1960.

the Sugar Pad and e Intermediate Terminal Building (2016)

Stone Brewery proposed tearing down rather than rehabilitating the 1938 warehouse in order to construct a restaurant, but demolition was not authorized. Redevelopment was complicated because water in a 100-year flood would rise four feet high on the bottom floor, but city officials decided the building could withstand such a flood without collapsing.

city officials issued a Request For Proposals in 2025 for redevelopment of the warehouse at Intermediate Terminal

Source: City of Richmond, Intermediate Terminal Building (ITB) Adaptive Reuse Redevelopment Request For Proposals

In 2025, Richmond officials issued a Request for Proposals from developers interested in converting the Intermediate Terminal warehouse in some way. The city was committed to revitalizing the waterfront, but not for industrial uses there.22

looking upstream from Rocketts Landing past Intermediate Terminal towards the skyline of Richmond in 2020

Deepwater Terminal remained active thanks in part to WestRock, formerly MeadWestvaco, shipping paperboard and other packaging materials.

The city owns the land at its port, but city staff do not operate the terminal. Richmond has leased the port to various private companies, starting with Richmond Waterfront Terminals in 1940. That private company installed cranes and other equipment needed to move cargo, scheduled the loading/unloading with different carriers, and managed the facility.

gantry crane at Deepwater Terminal before development of containerized shipping

Source: Library of Virginia, Deepwater Terminal (May 20, 1961)

In 1982, after the City of Richmond established an independent agency (Port of Richmond Commission) to replace the city's Public Works Department, the city leased the port to Meehan Overseas Terminal. Federal Marine Terminals purchased that company and operated the port from 1996-2009.

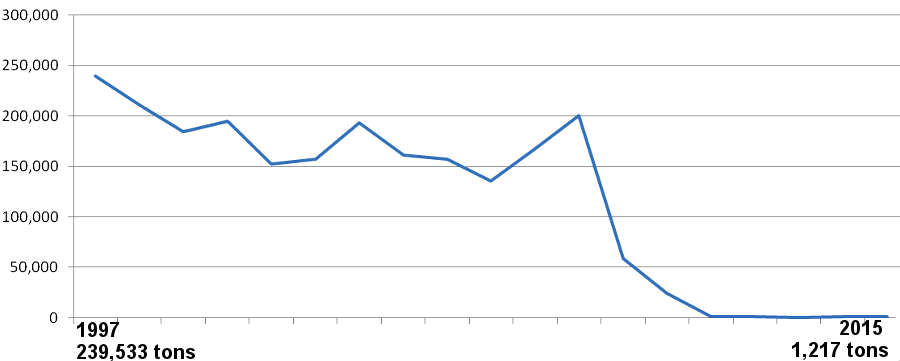

The 2008 recession reduced traffic, and then the terminal's main customer decided to stop service to Richmond. Independent Container Line moved its ships to the port at Wilmington, NC, largely because there was little cargo to transport out of Richmond. The cigarettes and other tobacco products once shipped from Richmond were being manufactured instead in Europe.

In addition, there were no lighted buoys to mark the shipping channel. Large commercial ships could not travel at night, delaying completion of the eight-hour trip up the James River.

Ship traffic to Richmond dropped by over 75%, and Federal Marine Terminals did not bid on the next contract to operate Deepwater Terminal. The city purchased all the equipment, and contracted with Port Contractors Inc. (PCI) in 2009 to handle cargo traffic at Deepwater Terminal.

the decline in the significance of the Port of Richmond is indicated by the statistics on exports, shown in Container Weight (tons)

Source: National Ocean Economics Program, Ports and Cargo - Foreign Trade Shipments

The city leased Deepwater Terminal to the Virginia Port Authority in 2011 and dissolved the Port of Richmond Commission. After signing the 40-year lease, the state invested in a new crane to speed the processing of containers. PCI continued as the terminal operator.

The Virginia Port Authority renamed the site, known as "Deepwater Terminal" between 1940-2016, to Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT). The state agency occasionally refers to it as the "Port of Richmond" (POR).

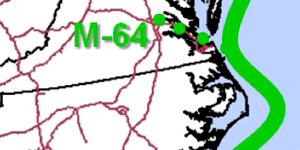

international ships have traveled up the James River since 1607

Source: Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, Executive Summary and 2019 Mid-term Transportation Needs for Northern Virginia Construction District

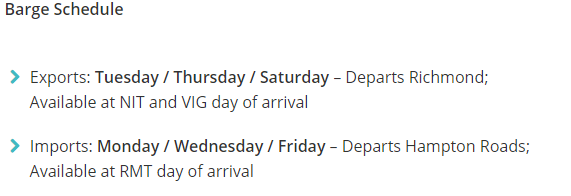

Richmond had used local, state and Federal grants to implement the "64 Express" in 2008 to carry containers between Richmond and Hampton Roads by barge. The Virginia Port Authority streamlined shipments so Richmond would handle just barges; all ocean-going ships now leave from just terminals in Hampton Roads. Barges bring containerized cargo upstream from the Hampton Roads terminals, a trip that requires 12 hours. Outgoing containers and bulk cargo (such as grain and scrap metal) is brought by trucks and the CSX railroad to the Richmond port, where it is loaded on barges to go downstream.

Barges loaded with petroleum products and aviation fuel can connect to both Colonial and Plantation pipelines at the port. Sand, gravel and crushed stone is transported by barge from quarries located upstream of the main wharf.23

at a quarry next to Richmond Marine Terminal, the bedrock that created the rapids in the James River (and made Richmond a port city on the Fall Line) is crushed and shipped downstream by barge

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2012, the Virginia Port Authority expanded the 64 Express to three trips/week. Creating frequent, reliable service was strongly encouraged by the Virginia Secretary of Transportation, Sean Connaughton, who had recently served as the administrator of the U.S. Maritime Administration. Expanding to three trips/week convinced Mediterranean Shipping to schedule regular service to Richmond.

Each barge carries 80-100 containers between Richmond and the Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) or the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminal. Barging containers up the James River on a "maritime highway" to customers at Hopewell and Richmond removes 12-15,000 truck trips per year from I-64, justifying the $2.3 million grant from the federal Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality program and a $200,000/year subsidy from the state.

the Maritime Administration has defined the M-64 Connector as a marine highway connecting Hampton Roads to Richmond

Source: Maritime Administration, Marine Highway Corridors

As a terminal operated by the Port of Virginia, Richmond was easier to market to the large international shipping companies. By 2016, 10 of the major carriers had created bills of lading defining Richmond as a destinations and point of origin for cargo that would be carried by the larger ships stopping at a Hampton Roads terminal.

The model for the 64 Express is the Virginia Inland Port at Front Royal. Containerized cargo unloaded in a Hampton Roads port is transported inland in double-stack trains to the Shenandoah Valley. Barging containers to Richmond is the equivalent of sending containers by train to Front Royal, except the Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT) is served by the CSX railroad and the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) is served by the Norfolk Southern.24

The president of Norfolk Tug Company, which pushed the barges, noted soon after the 64 Express service started in 2009:25

barges bring cargo containers up the James River to the Port of Richmond

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, James River Partnership Presentation 2017

In 2016, the city signed a 40-year lease of its land to the Virginia Port Authority, which renamed Deepwater Terminal to Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT). The long-term lease unleashed state-funded investments to upgrade equipment, including a new harbor crane costing over $4 million. Richmond officials planned for the 121-acre port to become a distribution center surrounded by warehouses similar to the Virginia Inland Port in Front Royal.26

Deepwater Terminal of the Port of Richmond

Source: City of Richmond, Port Aerial View

The Richmond Marine Terminal handled 10,000 TEU's in 2014, with barge service only three days/week. The Port of Virginia planned to increase that to seven days/week and boost the number of TEU's by 50%. The basic sales pitch for the Richmond Marine Terminal was location, location, location. A port spokesperson said:27

the James River Barge Service provides a weekly container-on-barge service from Hampton Roads to the Port of Richmond

Source: Port of Virginia, Gate Hours and Barge Schedule

One sign that the Port of Richmond could replicate the development around the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) was the 2017 decision by a private company to construct a new distribution center near the Bells Road-Interstate 95 interchange. Barge traffic had increased by over 1/3 in the previous year, and city officials were pleased with the ability of the Virginia Port Authority to increase business at the port.28

not all cargo to the Port of Richmond is transported by barge

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, James River Partnership - 2017 presentation (slide 78)

The Virginia Port Authority expanded the potential of the Richmond terminal by adding a central power unit to its barge, allowing transport of refrigerated containers required by the food and beverage industries. In 2017-18, developers committed to two major warehouse projects near the port. The private companies invested their funds, speculating that container traffic through the Port of Virginia would increase and new storage space would be required at Richmond.29

Barge traffic grew substantially each year after 2014. Volume of TEU's tripled to 34,200 in 2018, and a second barge was added that year. Each container shipped up and down the James River by barge took two truckloads off Interstate 64, reducing traffic going through the congestion at the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel and in Newport News. In 2019, the Executive Director of the Virginia Port Authority described the barge service as:30

Cost-effective, reliable transportation made the area around the terminal attractive for distribution operations. The grocery company Lidl, Lumber Liquidators, and others built warehouses nearby and increased demand for barge movements.

The number of containers moved by barge to Richmond Marine Terminal increased another 9% in 2020 to 57,000 containers, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The port had the capacity to handle 70,000 containers a year, plus 14 acres of undeveloped land for expansion.

Each barge could carry 125 containers, so a round trip kept 250 trucks off I-66 and US 340. The value of the barge operations was increased by arranging to ship agricultural products downstream from Richmond, rather than ship just empty containers to Norfolk.31

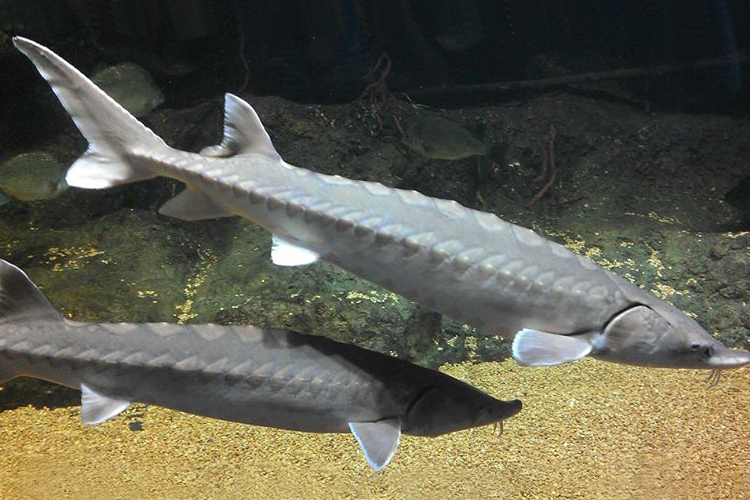

The US Maritime Administration's funding for the Richmond segment of the Marine Highway Program was questioned in 2021. The Center for Biological Diversity highlighted that the extra barge traffic on the James River increased the potential for collisions with endangered Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus). The National Marine Fisheries Service had listed the species under the Endangered Species Act as "endangered" in 2012, but no assessment had been made of the impacts of the Federal action to increase ship traffic in the sturgeon's habitat. Premature death by a vessel strike was a primary threat, since the number of adult spawning fish was so low.32

increasing the number of ships carrying cargo to Richmond also increased the risk of a vessel strike with an endangered Atlantic sturgeon

Source: NASA Goddard Space Fight Center, Steering Clear of Endangered Fish with NASA Data

The Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 included a threat to the plan to deepen the James River channel from 25' to 35' in depth, and enlarge the turning basin at Richmond Deepwater Terminal. The law streamlined the process to deauthorize projects that had not received funding for five full fiscal years (FY2013 through FY2017). The Corps anticipated this could happen for the James River in 2019, but to date the project remains authorized but unfunded.33

Port operations expanded in 2025 with the addition of three grain elevators built where cattle used to be penned up prior to shipment. Farmers found it easier to ship grain and soybeans by truck to Richmond, then use the barges to carry agricultural products to shipping terminals in Hampton Roads. The barges took 12 hours to get downstream and another 12 hours to be unloaded, but that two=step process was cost-effective compared to the expense of shipping by truck on traffic-clogged highways.34

Richmond developed as a port city because the James River is navigable upstream and downstream, but the Fall Line blocks ship traffic

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

between 1864-1940, the US Army Corps of Engineers cut and widened three channels through bends in the James River so longer ships could reach Richmond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the shipping channel to Richmond extends upstream from Newport News, in a channel dredged through Wreck Shoal above the James River Bridge

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 1-664 Bridge-Tunnel Study, Virginia Sedimentation And Circulation Investigation (Figure 4)