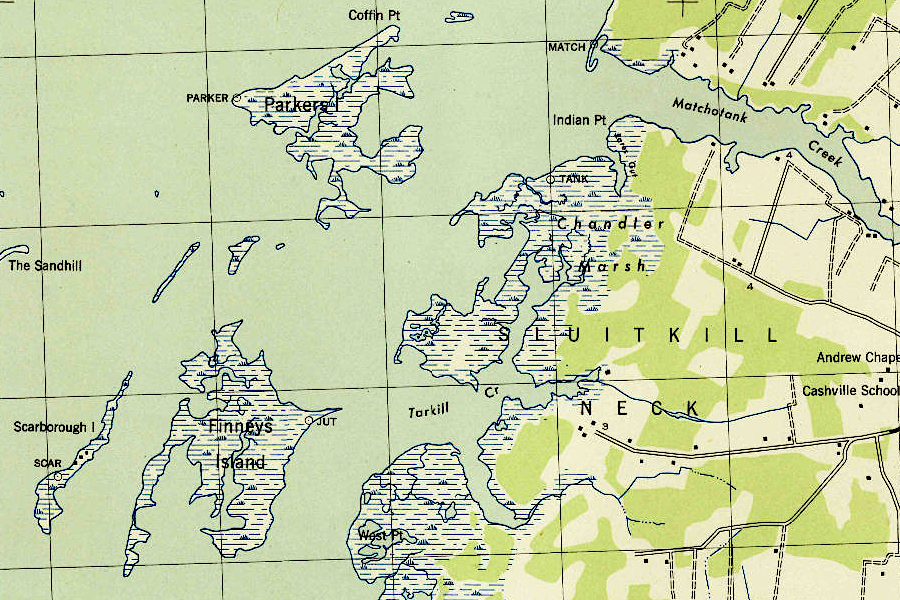

Parker's Island in 1943

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Pungoteague VA 1:31,680 topographic quadrangle (1943)

Parker's Island in 1943

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Pungoteague VA 1:31,680 topographic quadrangle (1943)

Parker's Island in 2008

Source: Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Parkers Island (by Jane Thomas)

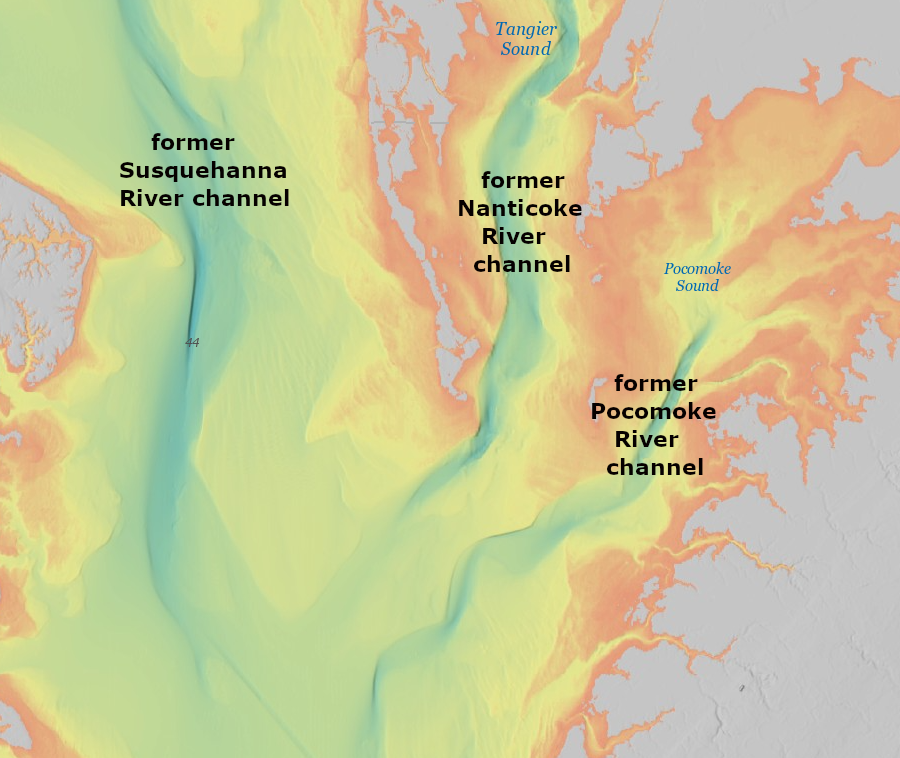

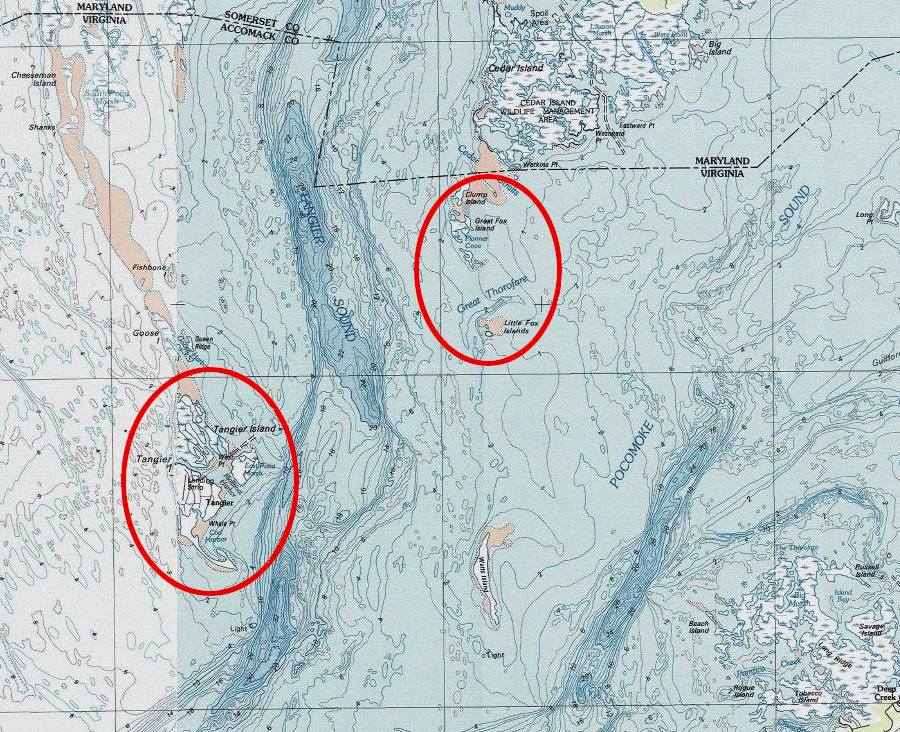

When John Smith explored the Chesapeake Bay in 1608, he discovered islands near the shoreline on both sides. Particularly on the eastern side of the Chesapeake Bay, those islands were the remnants of ridges which had formed watershed divides between rivers 18,000 years earlier when the Laurentide Ice Sheet stretched into Pennsylvania.

At that time, sea levels were 400 feet lower. Tributaries flowing into the Susquehanna River were separated by ridges which had formed during previous times of high sea level, when the Susquehanna River deposited sediments as it flowed into the Atlantic Ocean. When sea levels dropped, rainfall etched those sediments into hills and valleys creating topographic relief comparable to what is present today on the Coastal Plain. For example, the modern Rappahannock River is carving away at the base of Fones Cliff, cutting a river channel that is now 100 feet lower than the top of the cliff.

The Susquehanna River valley has been flooded as sea levels have risen, creating the Chesapeake Bay. Native Americans who began to live along the shoreline, just a few thousand years after the ice began to retreat, had to locate their campsites at a higher elevation as the Chesapeake Bay began to form.

When John Smith named the isolated islands, he was naming the highest parts of the old ridges which had not been flooded - yet. Had he arrived perhaps 2,000 years earlier, he would have seen peninsulas stretching from the Eastern Shore to what he named the Russells Isles. One resident on Smith Island has noted:1

the Russell Isles named by John Smith included Tangier, Watts, Smith and the Fox islands

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

Water levels in the Chesapeake Bay could rise another 2 feet by 2050, and up to 5.7 feet by 2100, and the islands are disappearing now for two reasons. The amount of water flowing into the Chesapeake Bay from the Atlantic Ocean has been increasing over the last 400 years. Glaciers and ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are melting, moving water that was frozen on the land into the ocean basins. To add to the increase in water flowing off the land, sea level is rising because the oceans are getting warmer as the climate changes. The water level in the Chesapeake Bay is rising in part because warmer water is expanding.

Unlike other areas on the East Coast of North America, land underneath the Chesapeake Bay is sinking. The crust of the earth is rebounding, slowly decompressing, where the weight of the now-melted glaciers has been removed. When the ice sheet extended to its southern limits, the crust was bent downward directly underneath the heavy ice, and that land is now rising. In New England, the coastline is rising up.

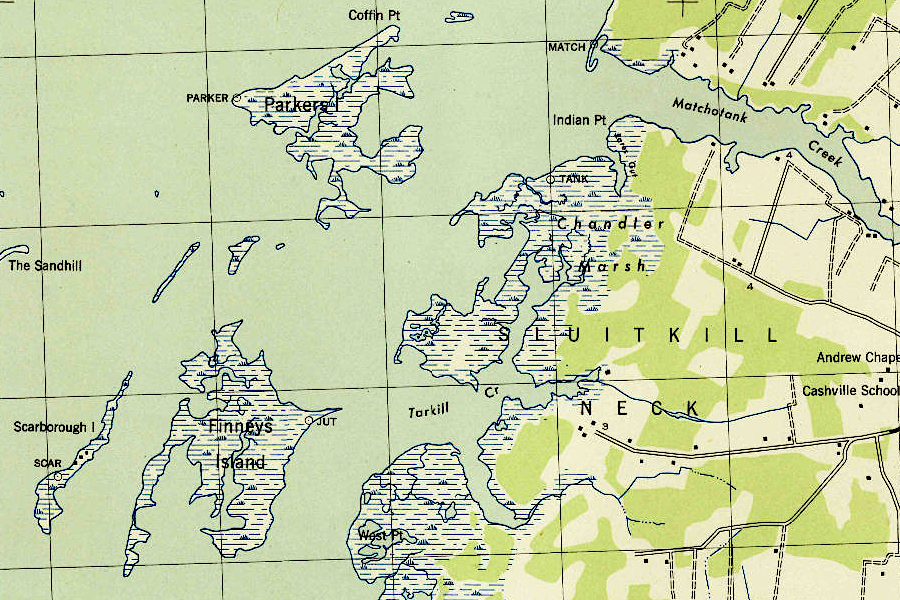

However, conditions were different 18,000 years ago about 100-200 miles in front of the ice's weight. There, the earth's crust was curled upward. The effect is comparable to the end of a see-saw where a person is sitting in one seat but the other seat is empty. When the person steps out of the occupied seat, the empty seat drops back down to be level with the other.

the land beneath the Chesapeake Bay is subsiding, while land directly underneath the ice sheet is rising

Source: Wikiversity, CDIO/Rube Goldberg 5 (by user Wsnyder0080)

Today, the uplifted curl is subsiding as the crust flattens out, matched by the rise of land that was once pressed-down. Due to land subsidence, the Chesapeake Bay is rising 4.6 millimeters per year while sea level worldwide is rising at 3.0 millimeters per year.

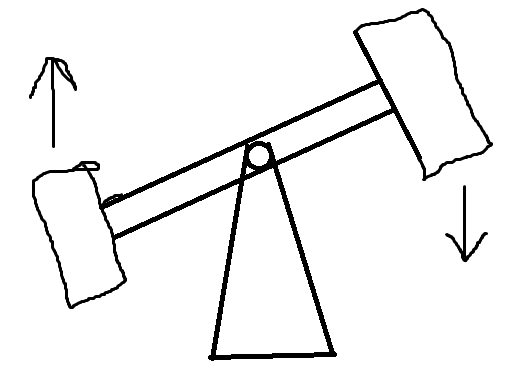

The subsidence is not fast enough to be visible to anyone looking at a shoreline, but the combined effects of slowly rising water and slowly sinking land have created obvious impacts. The Chesapeake Bay has drowned the channel of the Susquehanna River and the channels of its tributaries, and the old topography is revealed in bathymetric charts. Now the remaining ridgetops are disappearing, along with the cultural legacy of archeological sites which are being destroyed by erosion. An estimated 400 islands have disappeared over the last 400 years.2

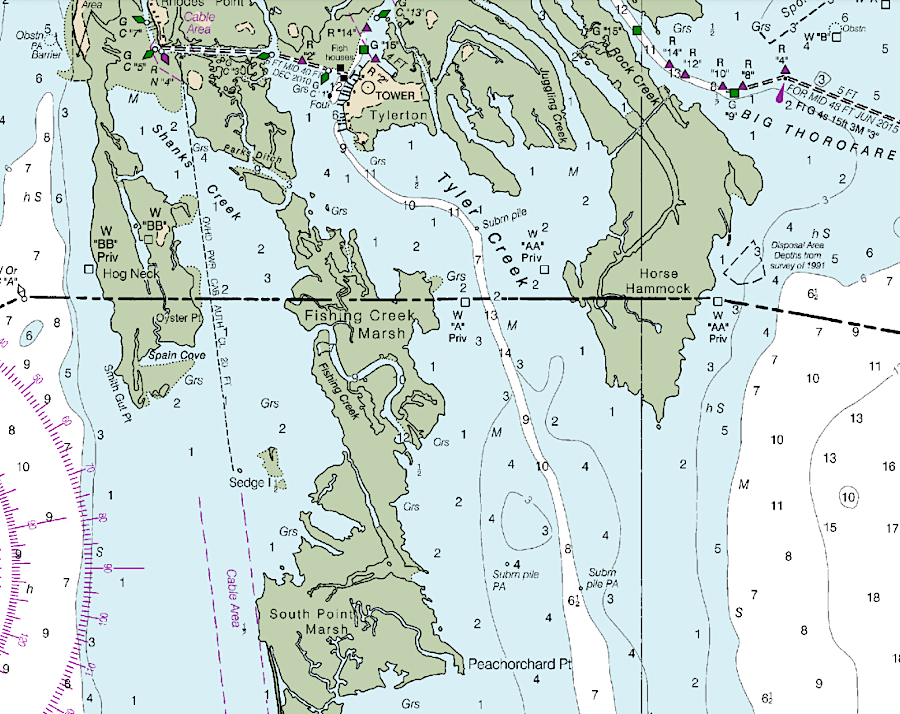

the former peninsula from Tangier to Smith Island (Tylerton) is mostly underwater now

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR) launched a Threatened Sites Program in 1985 to salvage information from archeological sites which would be lost to construction projects. It has funded efforts to document sites along the Chesapeake Bay which will be destroyed by erosion, as water levels continue to rise. An official with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) commented:3

channels of the Pocomoke and Nanticoke rivers, former tributaries of the Susquehanna River, appear on bathymetric maps now

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bathymetric Data Viewer

In the western side of the Chesapeake Bay, Gwynn's Island has been losing 1 acre/year for last 150 years. It is still over 1,400 acres in size, with a substantial number of houses and residents.4

On the eastern edge of the Chesapeake Bay, only one island within Virginia is still occupied. The population of Tangier Island has been dropping since the 1930's, but it still hosts a vibrant community and an organized town government. The residents have been identified as the first "climate refugees" forced to abandon a town in Virginia due to sea level rise, but many once-populated islands in the Chesapeake Bay and Wash Woods in Virginia Beach have already been abandoned.

Those living on Chesapeake Bay islands have had just three options. Those with access to substantial funding could armor the shoreline and build floodwalls to protect houses and other infrastructure. On islands with adequate acreage, residents could accommodate sea level rise by lifting houses higher or moving to higher ground. On small islands without sufficient resources to build seawalls or sufficient acreage to accommodate encroachment of the water, there was only one remaining option: evacuate.

Forced migration from Alaska villages and Pacific islands will affect more people than those living on Tangier Island. Streets and buildings in Annapolis, Maryland could experience almost daily flooding by 2045, unless they are elevated or protected by some form of barriers.5

the opening of an inlet connecting the western edge of Toms Gut to the Chesapeake Bay significantly increased the erosive power of storms and reduced the life expectancy of Uppards

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tangier Island VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2019)

Much of the remaining island acreage on the eastern edge of the Chesapeake Bay has been acquired by the Federal government or the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Many of those islands had been occupied in the 1800's, but residents left them as stormwater began to flood the land too often.

Virginia's most-northern island in the Chesapeake Bay is a portion of Smith Island. In 1877, arbitrators established the boundary across the Chesapeake Bay which separated Maryland and Virginia. They drew the boundary line across Smith Island. Today, Tylerton is an active port town on the Maryland side. Ewell and Rhodes Point are still occupied communities on the Maryland portion of the island as well, but there are no people living on the Virginia portion.

After Hurricane Sandy in 2012, Maryland officials sought to use $2 million in grants from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to purchase houses on Smith Island. The proposal would have reduced the number of structures at risk of damage in a future storm, and thus reduce long-term costs for disaster assistance and rebuilding. Residents almost unanimously rejected the proposal, recognizing that the businesses on the island could not survive if the population was reduced.

The residents banded together, held forums, and created a vision for long-term occupancy of Smith Island despite rising sea levels. The island's economy had been based on raising cattle in the 1800's, then on oystering, crabbing, and fishing. The vision anticipated tourism as the next evolution in making it economically viable for people to remain on Smith Island. Designation in 2008 of the Smith Island cake, with eight or more layers of yellow cake with chocolate frosting between each layer, as the official Maryland state dessert helped identify the place as "special" and attract tourists.

The life expectancy of the Martin National Wildlife Refuge was increased by adding a "living shoreline" to slow shoreline erosion. The US Army Corps of Engineers completed a $7 million project in 2018 to add two jetties and an 850-long stone sill at Rhodes Point. The new structures were designed to enhance navigation and shoreline resiliency at the same time.6

the Virginia portion of Smith Island has no residents now

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Booklet Chart: Chesapeake Bay – Pocomoke and Tangier Sounds, NOAA Chart 12228

About 65% of Tangier Island has disappeared since 1850, and it may not be inhabitable beyond midcentury. Residents on Tangier, like those living on Smith Island, identify erosion as the threat. From that perspective, an investment in constructing seawalls, living shorelines, and other shoreline stabilization infrastructure would be cost effective. Rock walls around the island would protect it for centuries if the only problem is wave action. However, if the cause of erosion is a combination of sinking land and rising sea levels, new protective infrastructure would provide just a few decades of benefits.

The tax base on Tangier Island is not adequate to fund seawalls or jetties. Because the Corps of Engineers prioritizes funding for navigation improvements, Tangier Island has received funding for jetties, channels, and harbor improvements. One project deposited dredge spoils on the western end of the island, raising it enough to build an airstrip. When erosion quickly threatened to wash away the pavement, the Corps of Engineers did build a 5,700-foot stone riprap seawall.

The Federal agency had declined to recommend the project because the benefit-cost ratio was below 1, but residents on Tangier Island are as determined to stay as the residents on Smith Island. They lobbied the US Congress successfully. It mandated construction in 1986, and the seawall was completed in 1990. In 2018, Federal and state government agencies agreed to spend $2.6 million to build a 494-foot stone jetty at the southern end of the Uppards, protecting the navigation channel leading from Mailboat Harbor to the western side of the island.7

The threats to Tangier Island received a burst of publicity in 2017. After CNN broadcast a story on the potential impacts of climate change on Tangier, President Trump called the mayor. He expressed his support for people staying on the island, and the mayor skillfully used the moment to highlight the need for Federal and state funding so that would be possible.8

No people have lived on Watts Island since 1936. Little Watts Island had a 48-foot tall brick lighthouse tower between 1833-1944. It collapsed after a 1944 storm, after most of the seven-acre island had already washed away. Today loblolly pine trees still grow on Watts Island, but Little Watts Island is just an underwater shoal.9

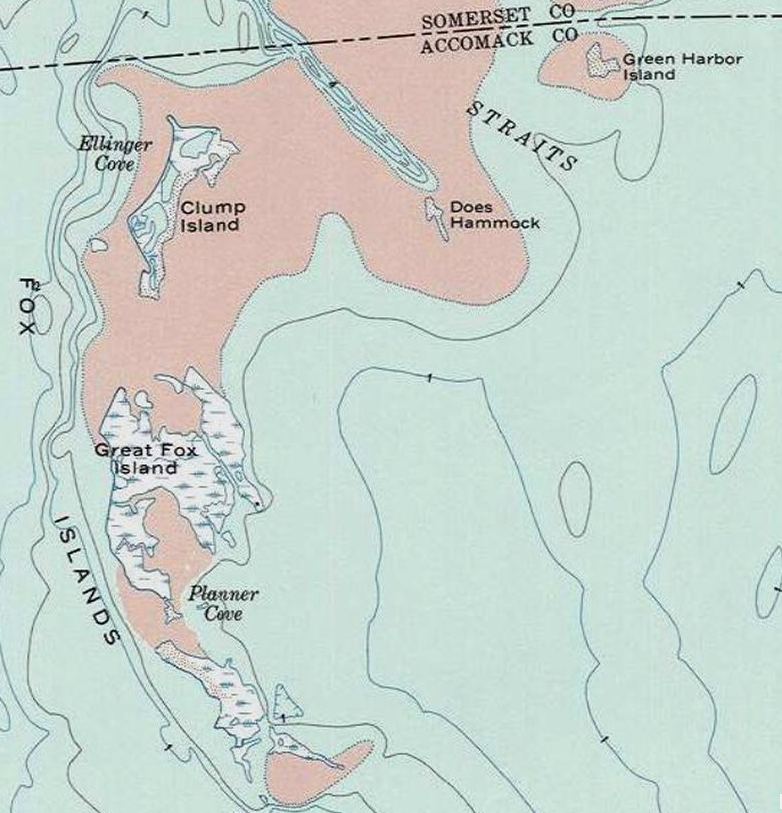

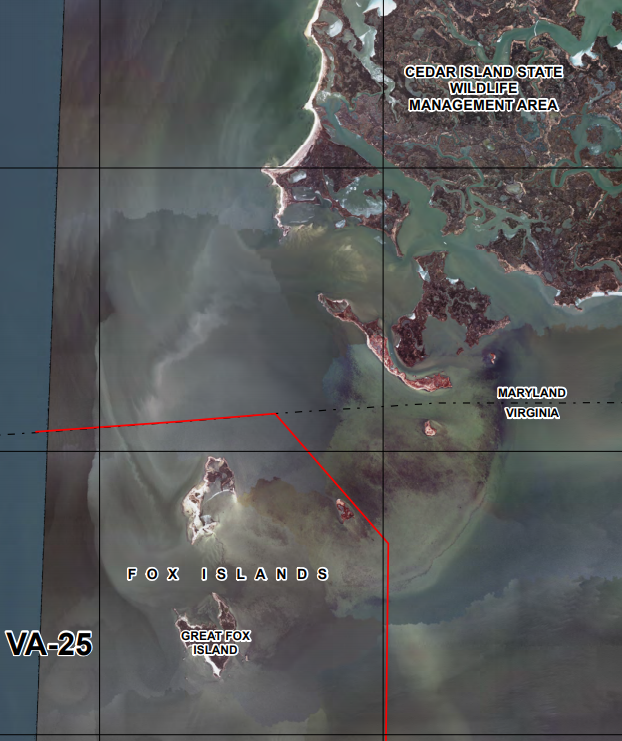

the Fox Islands are just south of the Maryland border established in 1877

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Great Fox Island and Little Fox Island were one hilltops on the watershed divide separating the Nanticoke River (now Tangier Sound) and the Pocomoke River (now Pocomoke Sound). Tangier Island is part of a different peninsula that once separated the channels of the Susquehanna and Nanticoke rivers.

Great Fox Island and Little Fox Island are part of a different ridge than Tangier Island, separated by the ancient river channel of the Nanticoke River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

During the American Revolution, Loyalists led by Captain John Kidd operated as thieves, raiding along the Chesapeake Bay even after Lord Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown. Maryland sent a fleet of four sailing barges in 1782 to expel them, but the Maryland force was defeated by Kidd at Battle of Cager's Strait on November 30, 1782. The commodore of the Maryland force was killed, together with about 30 of his men. The Loyalists ceased their piracy after learning that the American Revolution had ended with the 1783 Treaty of Paris.10

Hunters built a lodge on Great Fox Island in 1900, then rebuilt after it burned in 1920. They illegally baited waterfowl with corn until getting caught by a game warden in 1974. The judge offered the violators jail time, or they could donate the island. As a result, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation became the owner in 1975. The conservation organization opened the Fox Island Study Center and operated an environmental education program there. Students would stay for three nights while experiencing and well as studying the ecology of the bay.

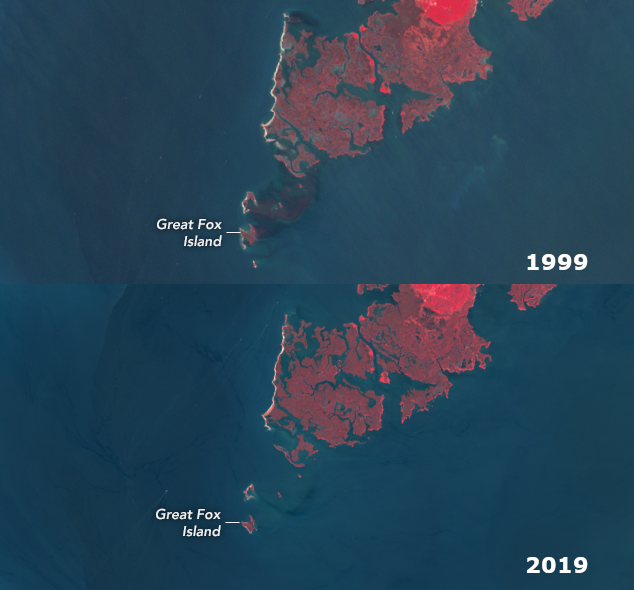

By 2019, the 423 acres mapped in 1773 had been reduced to 34 acres. The hunting lodge was exposed by the disappearance of the land and marshes which had protected it in a cove. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation concluded that it was no longer safe to continue the overnight programs. The risk was too high that a storm could flood Great Fox Island before students could be evacuated, so the foundation decided to move its programs to its facility at Port Isobel on Tangier Island.11

the shrinkage of Great Fox Island over 20 years is clearly visible

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) - Earth Observatory, Great Fox is Disappearing

Greater Fox Island is within Unit VA-25 in the Coastal Barrier Resources System

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Coastal Barrier Resources System

Great Fox Island, with the hunting lodge, was sold for $70,000. The buyer could not obtain Federally-subsidized flood insurance, because Great Fox Island had been incorporated into Unit VA-25 of the Coastal Barrier Resources System when owned by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. All 466 acres were listed as aquatic habitat (marshland and open water between the marshes), and none was identified as "fastland" (uplands, above mean high water).

The former Chesapeake Bay Foundation education center burned down to the pilings on the night of February 9, 2024.12

Source: Chesapeake Bay Jornal, Fox Island loses battle with a rising Bay (2019)

Shark Tooth Island, in Currioman Bay along the Potomac River, lost 32 acres (half of the sandbar) and essentially split into two parts between 1994-2024. The island is named for its accumulation of sharks teeth, captured with Miocene Epoch sediments that erode out of the Potomac Formation such as the cliffs at Westmoreland State Park upstream. The privately owned island allows public beachcombing visits several times a year for fossil collectors.

At the island, sea level rise and land subsidence combined were 1.5 inches every 10 years. Shark Tooth Island was only several inches above sea level in 2024. Unless a storm deposited sediments, its future as an island was doomed. A teacher at Mary Washington University was succinct in his assessment regarding the rate of deposition and submersion:13

Shark Tooth Island split into two parts between 1994-2024 (Westmorelsand County)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Much of the remaining land and marsh of the Chesapeake Bay islands is included within the Coastal Barrier Resources System. That limits the development potential by blocking use of Federal funding for projects.

A particularly significant deterrent to new construction on the islands is that new development, within designated units of the Coastal Barrier Resources System, is not eligible for flood insurance policies that are issued under the Federal Emergency Management Agency's (FEMA) National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Financial institutions are rarely willing to approve a mortgage on such properties, unless the owner purchases private insurance at a much-higher rate based on actual risk. In addition, rebuilding is limited because structures which lose over 50% of their market value in a storm, fire, or other event are not eligible for renewal of Federally-supported flood insurance.14

Congress defined the initial boundaries of the Coastal Barrier Resources System in 1982, then updated them in 1990. Only Congress can add lands now, with three exceptions. The US Fish and Wildlife Service, which is responsible for documenting units of land within the Coastal Barrier Resources System, can modify a map delineating what land is within a unit through administrative action only when natural forces alter the shoreline, Federal property which qualifies for inclusion is declared excess (such as part of a military installation being closed), or when landowners voluntarily request inclusion.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation has proposed expanding the Coastal Barrier Resources System to include land the foundation owns on Chesapeake Bay islands. Incorporating its land within a designated unit of the system gives it greater protection from development, compared to having the land classified as "Otherwise Protected Area." In 2018, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed expanding Unit VA-26, Cheeseman Island, Virginia from 1,101 acres to 5,347 acres.

The change would not increase the amount of "fastland" (upland, or dry land above the high water mark) within the unit. That would remain at just 12 acres. However, the delineated boundaries extending from fastland would be expanded to include 4,246 more acres of aquatic habitat - wetlands, marshes, estuaries, inlets, and open water landward of the coastal barrier.15

Cheeseman Island is within Unit VA-26 in the Coastal Barrier Resources System

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Coastal Barrier Resources System

in 2018, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed expanding Unit VA-26 to include Fishbone Island and Goose Island

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, CBRS Projects Mapper

the life expectancy of Fishbone Island, Goose Island, and Queen Ridge can be measured in decades, before they too become underwater shoals

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Tangier, Goose and other Chesapeake Bay islands were much larger in 1670

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman)

Sea level rise is causing islands in the Chesapeake Bay to disappear, but could also create a new island in Accomack County. Saxis Road (Route 695) links the Town of Saxis to Route 13 in the middle of the Eastern Shore. The shoreline with the Chesapeake Bay is retreating by nearly five feet per year, and storm surges and rising tides flood the highway once a month where it passes through a low marsh.

After Hurricane Sandy in 2012, a boat blocked the road. The mayor viewed that storm as a local benefit because funding was provided afterwards to raise houses, dredge the harbor, and build artificial reefs. At least 10 more houses still needed to be raised. A new superstorm might damage the town, but might also provide a new surge of funding for larger culverts on Saxis Road, jacking up more houses, and building more shoreline storm surge barriers.

According to the Resilience Adaptation Feasibility Tool (RAFT), SAXIS scored 54 on a scale of 100. The Saxis Resilience Implementation Team used it to identify how to communicate evacuation plans and assess who would be staying in town when storms hit.

As sea level rises the town will be isolated as a new island. One resident noted how Saxis compared to other Chesapeake Bay islands:16

Saxis has always been perceived as an island, despite its physical connection to the mainland. When first patented in 1666 by Robert Sikes and George Parker, it was known as Sikes' Island.17

Some disappearing islands are being "saved," using the dike-and-deposit strategy endorsed by residents of Tangier Island. Craney Island near the mouth of the Elizabeth River could have been diminished by sea level rise and erosion, but instead has been expanded. Sediments dredged for Chesapeake Bay and Tidewater rivers have been deposited on the island, expanding it greatly to form the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area.

In Maryland's portion of the Chesapeake Bay, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Maryland Port Administration have deposited dredge spoils to rebuild multiple islands. As first envisioned in 1970, a dike was built around Hart and Miller islands in 1981 and dredge spoils from Baltimore Harbor were pumped over the dike between 1984-2009. Today the 1,100-acre Hart-Miller Island is a Maryland state park.18

sediments dredged from the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay for 25 years to maintain shipping channels have been used to create the new Hart-Miller Island

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Hart-Miller Island State Park in the Chesapeake Bay; Maryland Port Authority, "Hart-Miller Island - Birds Eye View," https://maryland-dmmp.com/placement-sites/hart-miller-island/

Other island restoration projects have included Battery Island near Havre de Grace, Barren Island in Dorchester County, and Swan Island next to Martin National Wildlife Refuge.

A dike was completed around Poplar Island in 2001, then dredge spoils were added from Chesapeake Bay shipping channels such as the Chesapeake and Delaware (C&D) Canal's southern approach. Poplar Island had shrunk from 1,140 acres in 1847 to just five acres in 1996. When the project is completed around 2030, the island will have approximately 829 acres of upland habitat, 776 acres of tidal wetlands, and s a 110-acre open water embayment

The next site to receive spoils will be James Island, near the mouth of the Little Choptank River. A stone dike 20' high will contain the sediment when it is pumped into holding cells inside the dike. Because the dredge spoils will come from the Upper Bay and not the Baltimore Harbor, the Army Corps of Engineers predicts little contamination from industrial pollution.

About half of James Island will ed up as wetlands, with an even split between high and low marsh vs. the creation of 80% low marsh at Poplar Island. One wildlife habitat technique to improve upon Poplar Island was to expand the width of channels from the island edge into the wetlands and embayment, to make it easier for fish to move back and forth. An Army Corps of Engineers planner described the benefits of "lesson learned" that can be applied to the James Island project:19

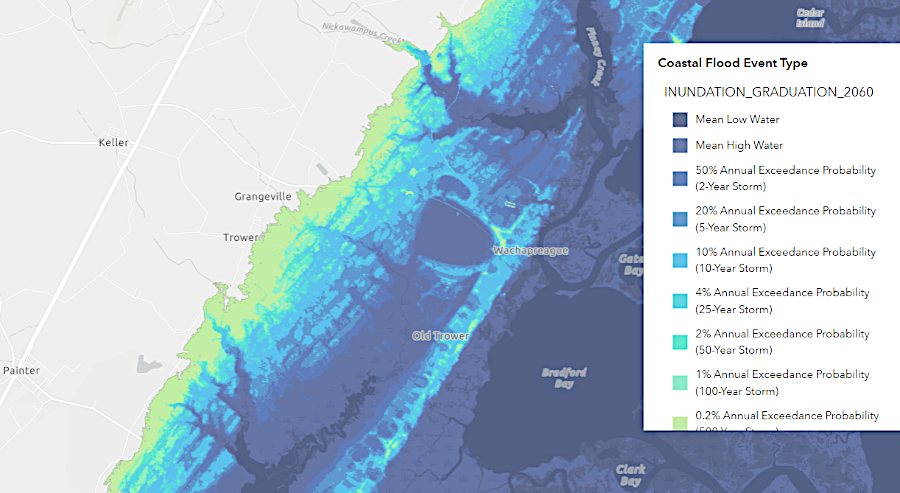

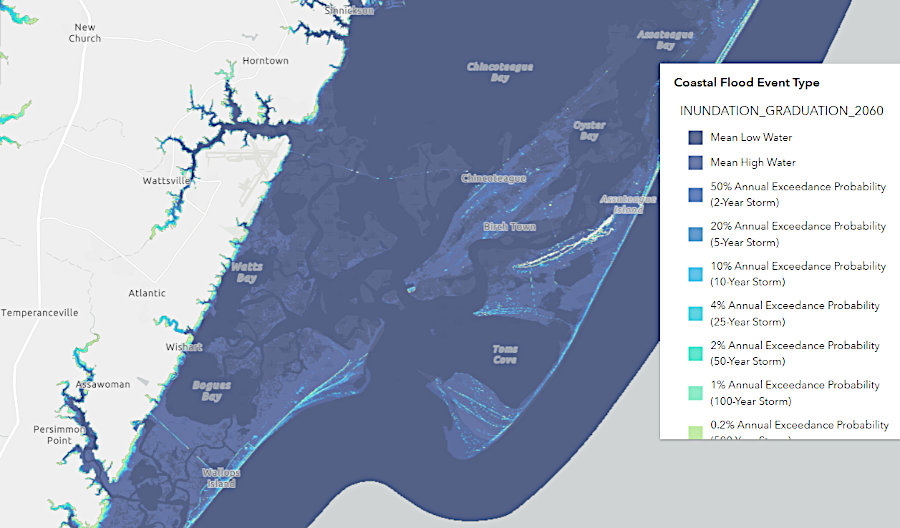

by 2060, barrier islands and shoreline communities on the eastern side of the Eastern Shore are predicted to disappear

Source: Virginia Coastal Resilience Web Explorer

dredge spoils are expanding Poplar Island from 5 acres to 1,715 acres in size

Source: ESRI, arcGIS Online; Wikipedia, Poplar Island (Chesapeake Bay)