poison ivy on cherry tree, Manassas battlefield (Prince William County) |

interrupted fern, Shenandoah National Park (Greene County) |

fire azalea on Warspur trail, Salt Pond Mountain (Giles County) |

poison ivy on cherry tree, Manassas battlefield (Prince William County) |

interrupted fern, Shenandoah National Park (Greene County) |

fire azalea on Warspur trail, Salt Pond Mountain (Giles County) |

Virginia is a great place to live - according to some people. Others can't stand the place.

Plants and animals operate the same way. Some find the places in Virginia, the habitats, to be good neighborhoods. Others visit for a period of time each year, then leave. And a lot of plants and animals are never found naturally in Virginia; this is not the place for them. Manatees and humpback whales show up occasionally in the bay, but just as short-term visitors.

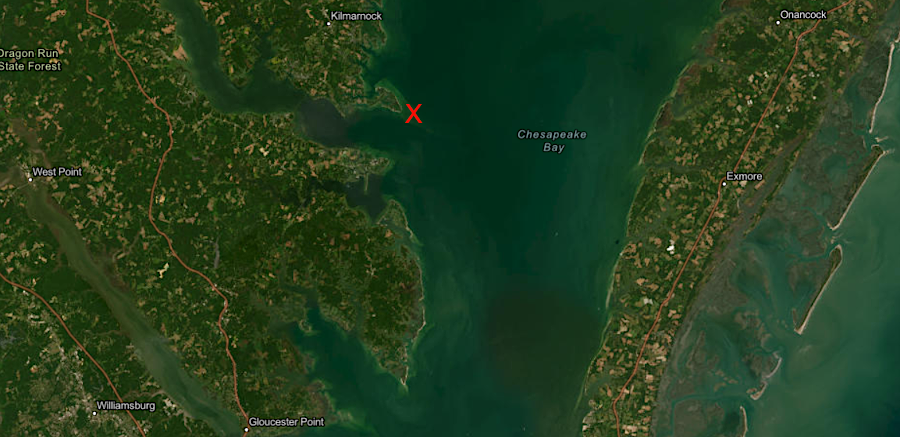

a stranded manatee was rescued from a pound net near Windmill Point (red X) on August 27, 2023

Source: Virginia Marine Police and ESRI, ArcIS Online

Virginia's soil, climate, and even location on the eastern edge of the continent determine which species live here. The effects of the climate are most obvious. In the early summer, the woods are full of bird calls. Come winter, however, and many of the songbirds have migrated south. In return, Virginians get to see juncos and snow geese, visitors from the north who consider Virginia's winters to be mild compared to Canada.

Virginia has magnolia trees and bald cypress; we are a "southern" state. Walk around First Landing State Park, and it's not hard to imagine yourself being in a Louisiana swamp, but winters are too cold for banana trees to survive without protection. Virginia's latitude is 1/3 of the way north of the Equator towards the North Pole. Virginia has a temperate, not a tropical climate.

As the climate warms, armadillos and fire ants are expanding their ranges into Virginia. Manatees, harbor and even gray seals are becoming more common in the Chesapeake Bay. Populations are increasing and traditional habitats are getting more crowded, so extension of the ranges into marginal territory is to be expected.

The spotting of a Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) in the Chesapeake Bay in 1994 was a major news story. Wildlife officials feared "Chessie" would not swim south back to Florida before the water became too cold (below 68 degrees) for survival.

Because manatees are protected under both the Endangered Species Act and under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies captured Chessie. They kept the manatee briefly at the National Aquarium in Baltimore, then flew it back south for release at Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge near Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Chessie returned to the Chesapeake Bay in 1995, and explored north all the way to New Haven, Connecticut. In 1991 he was spotted again (thanks to distinctive scars on his fur) at Great Bridge Locks in Virginia Beach, and once more in 2011 in the upper Chesapeake Bay waters of Maryland. Manatees are routine visitors to the Chesapeake Bay now, appearing annually. Sightings have been reported in the brackish sections of the Rappahannock, James and Appomattox rivers.

The manatees are also appearing earlier. In 2024, when one was spotted at the in June in Virginia Beach's Lafayette River and Rudee Inlet, the local paper reported:1

since Chessie was spotted in 1994, sightings of manatees in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries when the waters are warm have become a common experience

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Famous Manatee Sighted in Chesapeake Bay After Long Absence

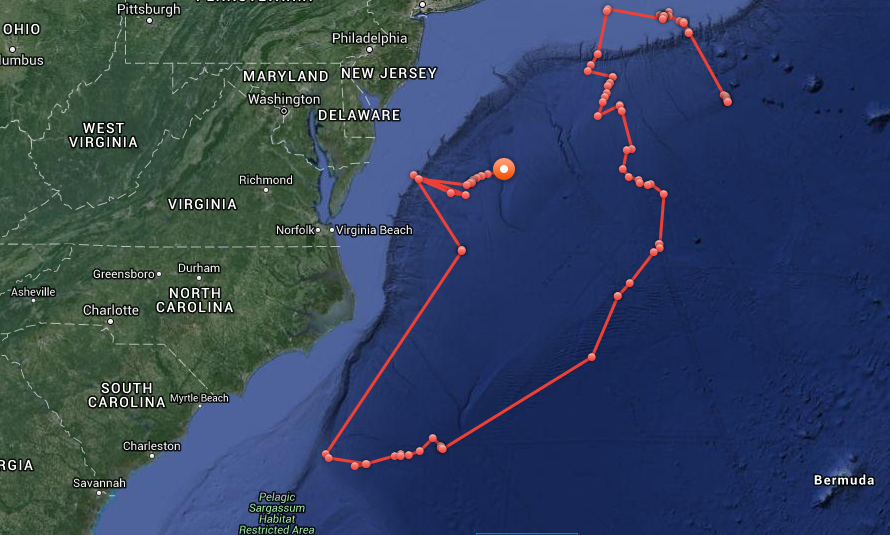

Harbor seals, traditionally wintertime visitors between October-April until waters off the New England coast warm up, are seen more often now near the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel islands and on Eastern Shore beaches. If the gray seal population also expands into Virginia waters, then their predator - white sharks - may become more common. More shark spottings could affect tourism at Virginia's beaches.

March/April, 2016 track of a great white shark named Mary Lee by researchers

Source: OCEARCH, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

Increased seal populations could also affect training by the US Navy. When spotted close to ships, sonar operations are constrained. The underwater sounds are disruptive to the protected seals, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act prohibits "harassment" of protected species.2

harbor seal range expansion into Virginia currently involves adults, who are typically seen after climbing onto rocks to warm themselves in the sun but also choose gently sloping beaches

Source: Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, Seal, Sea Lion and Sea Otters

Virginia provides a suitable place to live in different seasons. As seasons change, the habitats change.

The most obvious change is in the forests - when the leaves drop, much of the food and shelter required by some species disappears too. Many species of animals, such as neotropical birds, adapt to the changing circumstances by picking up and moving. At just about the time students migrate to college campuses, birds start flying south. Female blue crabs migrate to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, walking on the bottom of the estuary as much as 150 miles to find higher-salinity water for the winter.

Plants lack the option of moving. Even the "walking fern" can only move a few feet a year, at the most. Plants adapt by winterizing. They drop their water-filled leaves that are vulnerable to freezing, drain their sap down into the roots, or produce hard-coated seeds that can survive the winter while the annual plant itself dies.

the tip of the walking fern will root and start a new plant, enabling the plant to move - slowly - to new habitat

Source: National Park Service, Ferns

In the spring, sap rises through the phloem cells in trees to supply nutrients to growing leaves and branches, as water rises through the xylem cells. Those specialized vascular cells just below the bark enable nutrients and water to move from roots to the tops of trees, some of which reach over 100 feet in height.

In Highland County, March is the time for capturing the tree's food and making it into maple sugar. Sap rising from the roots of sugar maple trees is intercepted in the early spring, then concentrated through boiling into maple sugar. The Highland Maple Festival has attracted tourists to Monterey each spring since 1958. In the fall, the colorful leaves draw tourists back to the cool mountains.

If temperatures climb over the next century, oaks, hickories, and other species better adapted to warmer temperatures may out-compete the sugar maple (Acer saccharum). Sugar-making in Virginia's mountains may disappear as a result of anticipated climate change.3

Source: Wikipedia, Acer saccharum

To understand the different ecological niches and biological communities in Virginia, and especially to understand whether the cumulative impacts to those natural areas of development of roads/subdivisions is acceptable, it is necessary to identify individual species that live in Virginia. That's not as easy as distinguishing between a NASCAR race and a football game on the television.

bluebell flowers near Cedar Run at Merrimac Farm Wildlife Management Area

Trying to define the boundaries of life can induce a headache. Are bacteria in the same category as viruses? Should fungi and lichens be treated as one lump or two? Should ferns and flowering plants and conifers (such as pine trees) be three categories... or many, many more? It's tempting to say "this is alive, and that is not" - but are viruses and prions alive?

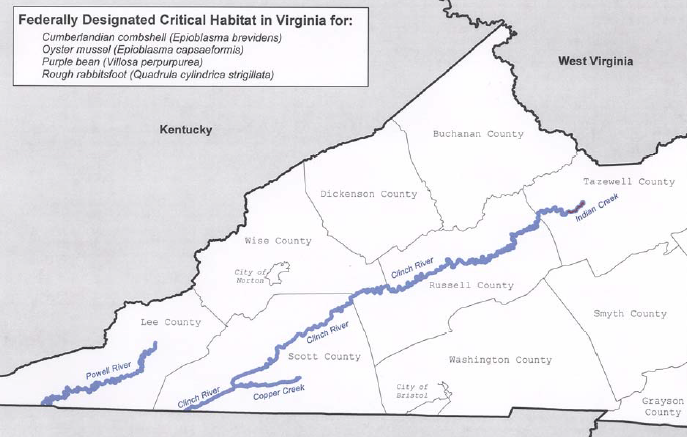

Simplistic answers may be attractive, but they are rarely useful. Impacts of altering the natural setting can be subtle and cumulative. If a series of boat docks are constructed in the Clinch River where mussels are reproducing, with each dock disturbing a sandbar only slightly, the total destruction of the mussel population can occur without anyone noticing.

some mussel species in Virginia can live for over 100 years, if their habitat is not altered by excessive silt from upstream construction

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Mussel Guidelines

When the state tries to build a highway through an undeveloped natural area using Federal highway funds, government agencies must complete an Environmental Assessment (EA) or occasionally a more-detailed Environmental Impact Study (EIS). The analysis is mandated by the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) for projects involving Federal resources. It is common to hear complaints that the species inventory and other aspects of environmental analysis cause too much delay and expense.

NEPA-mandated analysis is designed to help officials decide on the significance of a place, and how alterations in the habitat might created unintended consequences. Some habitats are common in Virginia, and destruction of a few acres of forest may be significant only to the trees and critters that live in that specific location. If an archaeological site, historic structure, "specimen tree" of unusual size, or a nest of an endangered species is identified in the inventory of potentially-affected resources, the typical solution is to move the project (such as a highway) a few feet to avoid damaging the resource.

farms, roads, and power lines fragment forests and create open areas,

reducing the wood thrush population but increasing the habitat suitable for bluebirds

(Salt Pond Mountain, Giles County)

But should the road be moved north through that pasture, the one over there with the wildflowers blooming on the edge... or south through that pine plantation? Planted pines are not "natural," after all. However, if you are near the Sussex and Southampton counties, you could be looking at a rare longleaf pine forest that provides shelter for the even-rarer red cockaded woodpecker. Which location is less valuable than the original route? Which habitat for individual species, or which habitat for "ecological community groups" (species that tend to live together), is more valuable?

To answer that question, scientists try to categorize ecological communities, then inventory them, then assess the impacts of the alternatives to the proposed action (such as building a road here vs. there). A taxonomy of places is essential for an apples-to-apples, oranges-to-oranges discussion. Some communities, like species, are "critically imperiled" and ranked as G1, or rare on a global scale. If rare at the national or state level, rankings are N1 (national) and S1 (state).

On the other end of the scale, common/widespread/abundant communities are ranked G5, N5, or S5. In most cases, changes to the landscape in G1 locations create far greater environmental damage than in G5 locations, because it is harder/impossible to replace a G1 community. Typically an EA/EIS will steer decisionmakers to protect the rare places, and put development where it will affect only the common communities.

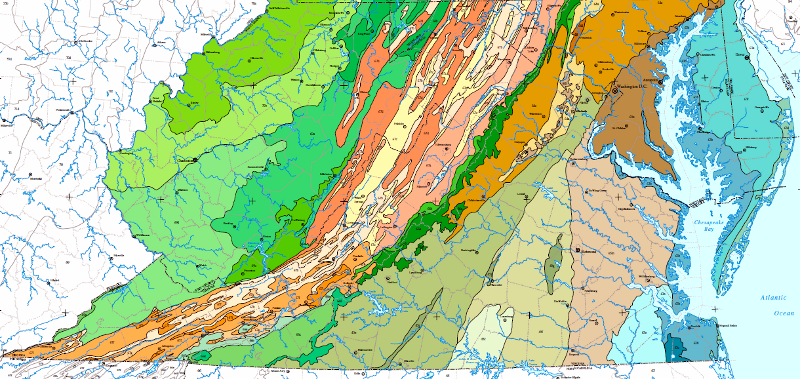

On a broader scale, a series of communities can be lumped into ecosystems. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has defined four levels of ever-more-detailed ecoregions of Virginia.

The Environmental Protection Agency says:4

Level III and IV Ecoregions of EPA Region 3

Source: Environmental Protection Agency

Take a close look outside the car window, the next time you are trapped in traffic. Notice the different types of plants along the roadside. Do this several times, and you'll begin to see the pattern.

Some places are treeless, such as the mowed edges of the roads or the medians in divided highways. Here you'll find wildflowers such as Queen Anne's lace (the big white blooms that look sort of like an umbrella) and chicory (blue flowers hardy enough to grow among the gravel). Look at the forested areas, and notice how few wildflowers are visible on the ground. The trees are capturing all the sunlight, shading out the forest floor beneath. Even at 55 miles per hour, you can see some forests are thin-needled pine trees and others are broad-leaved oaks, maples, etc.

deer avoid eating the native spicebush (Lindera benzoin) and the non-native, invasive Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) (Manassas battlefield, Prince William County)

Now look closely at those pine forests - what trees are growing up underneath the mature ones? Along I-95 in the summer, you can see the sweetgum and other broadleaved species are the "understory," the young trees underneath the overstory of mature pines. In 50 years or so, those pines will have died - and their replacements will not be more pine tress. Instead, a broad-leaved forest will replace the pine forest, in a pattern known as "succession."

Look at old fields in suburbia, after farmers quit raising corn or grazing cattle. First weeds fill the fields. In the Spring, a species of mustard can carpet the entire field with yellow. In the Fall, different species (often a Coreopsis or goldenrod) can create the same effect.

coreopsis on roadside at Rosewell (Gloucester County); goldenrod on Dogan Ridge at Manassas Battlefield (Prince William County)

View the field 10 years later, and young trees will be growing in the field. In the limestone soils of the Valley and Ridge province, look closely and you'll notice (typically) that the trees are red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) rather than the Virginia pine so common on the Piedmont and Coastal Plain. Look again 20 years later, and the weed-filled field will be a young forest, often a dense thicket of pines or cedars. If you could come back in 100 years, however, you'd see the progression to the "final succession stage" or "climax forest" of oaks, hickories, beeches, etc.

cedars on left, transforming an old field into a young forest

It's not quite that simple, naturally. Normally, succession without intermittent disturbance would be rare - there's always a hurricane, a forest fire, a disease outbreak every century or so. With humans creating such disturbance in the environment, our only opportunities to study this process over decades could be limited to those few areas designated as parks.

with over 40" of rain annually in Virginia, trees will grow in abandoned fields and convert them into forests within a century (Brawner Farm, Prince William County)

Gardeners are well aware of the difference between shade plants (such as ferns) and plants that require full sun (such as tomatoes). You can appreciate the geography of Virginia's plants without knowing the names of the trees and flowers. Use your eye to notice where you see things. Start with large patterns such as sunny vs. shady locations, and work your way towards a greater appreciation of the diversity of habitats and species in Virginia. If you don't see the differences, if all the plants look the same to you, then it's hard to understand efforts to protect the rare species. There are some people who could eat the same macaroni-and-cheese meal for breakfast, lunch, and dinner too... but if you are more sophisticated in your food selection, you can be more sophisticated in your understanding of ecological places too.

wild ginger, flowering

Since the development of life on Earth, the mix of species has always been dynamic. Initially chemosynthetic bacteria dominated the oceans, while the land masses were barren. Cyanobacteria transformed the Earth about 2.5 billion years ago, as their photosynthesis pumped a poison into the atmosphere. In a worldwide mass extinction, the chemosynthetic bacteria were killed off by that poison - oxygen.

After the Great Oxygenation Event, other photosynthetic species evolved. Some developed cell walls with a coating that could retain moisture when exposed to the air.

About 400 million years ago, Rhynia managed to survive on land. It evolved with stomata, cells that opened or closed to allow carbon dioxide to reach photosynthesizing cells but avoid dehydration. Many species developed a vascular system to transport nutrients up from the soil and carbohydrates down from the leaves, along with a parnership with soil fungi to transport water and chemicals into the roots.

Today, humans have identified perhaps 0.001% of all microbes. Excluding bacteria, an estimated 8.7 million eukaryote species have evolved on Earth, and 85% are insects or closely related to them. If the estimate of 7.77 million animal species is correct, then 88% of them remain to be classified by taxonomists.

Each year, botanists identify 2,000 new plant species. By one estimate, 80 percent of the planet's total biomass is in the form of plants.

The co-founder of the Census of Marine Life and the Encyclopedia of Life said regarding biodiversity:5

Burkes Garden, one of the biologically-rich areas on Southwestern Virginia (and known sometimes as "God's Thumbprint")

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Burkes Garden 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (1941)

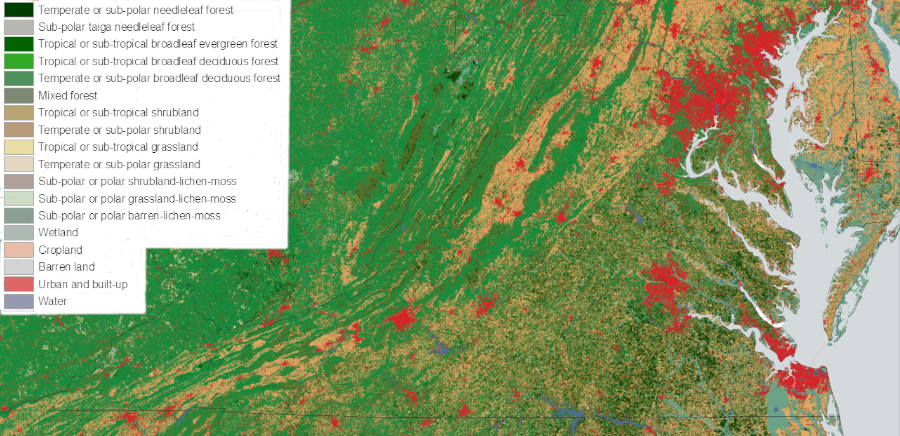

At one time, the habitats and species of Virginia were very different from what you see today. In the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous eras, dinosaurs thumped through "forests" of Virginia ferns and cycads and left their footprints in the sediments. Only in the last 15,000 or so years have humans been one of the species affecting the habitats in Virginia. Current land use maps reveal the transformation over time.

red areas are "urban or built-up," where transformation of the landscape has been most intense

Source: Commission for Environmental Cooperation, North American Environmental Atlas

Twice, different sets of "discoverers" adapted the resources here to suit their needs, changing the face of Virginia in the process. Once the Native Americans began to clear spaces for agriculture, they created new habitats for species such as deer that prefer a mix of forests and fields. Native Americans domesticated the wild wolf, and had dogs as companions - and as a source of food, too. (Lewis and Clark, when in Oregon, grew tired of eating elk and welcomed a meal of dog.)

Starting in the 1500's, Europeans started to bring their species to Virginia. Today, the habitats and species that inhabit them have been transformed. It is hard to establish a baseline of what species are "native" to the Chesapeake Bay, since ships have carried so many hitchhikers from Europe,, Africa, South America, and the Caribbean. Anglers fishing for bass assume the smallmouth and largemouth are native to the Shenandoah River, when in fact they were unable to get past Great Falls naturally.

Federal agencies manage lands for natural resource use, together with conservation of habitat for plants and animals. Different agencies have different priorities. The US Forest Service is a multiple use agency which authorizes mining and timber harvest except within ars designated as wilderness. The US Fish and Wildlife Service prioritizes increasing waterfowl populations in multipe Tidewater refuges, but also focuses on species of special concern such as bald eagles. Recreational use of wildlife refuges is limited to activities that should not interfere with wildlife, and areas within a public refuge may be closed during nesting seasons.

The National Park Service encourages recreation and education at places such as Shenandoah National Park and the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. Camping and fishing are encouraged in Virginia's national parks and the Blue Ridge Parkway is a very popular rout for motorcyclists, but people looking for a place to drive off-highway vehicles on Federal land in Virginia must find designated areas for that recreational activity in a National Forest.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) partners with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) to manage four separate units that compose the Chesapeake Bay-Virginia National Estuarine Research Reserve. Though used for general public recreation, the Chesapeake Bay unit within the National Estuarine Research Reserve System emphasizes research used to develop science-based solutions for the protection and management of estuaries.

Virgina has systems of state parks, forests, and wildlife management areas that parallel the management objectives of Federal parks, forests, and wildlife refuges. State lands offer tourism and recreation opportunities; local communities highlight them with hopes of generating economic benefits from visitors.

Virginia also has programs designed to preserve rare and sensitive species and habitats, even though the economic benfits of the ecologicaal services they provide are hard to quantify. In some jurisdictions, local governments typically focus on providing active recreation opportunities such as soccer fields and basketball courts. However, some local governments also own land or conservation easements intended to protect special habitats.

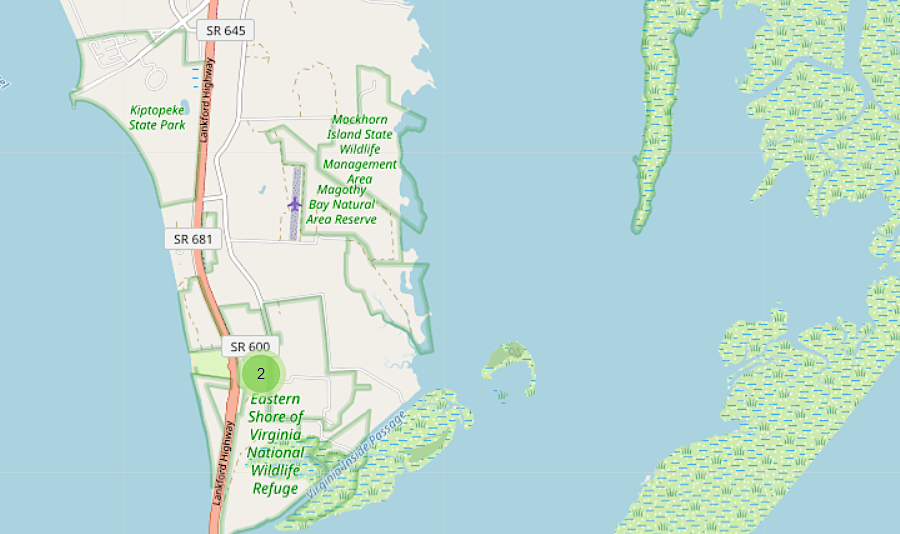

different state and Federal agencies manage natural areas at the southern tip of the Eastern Shore

Source: US Fsh and Wildlife Service, Our Facilities

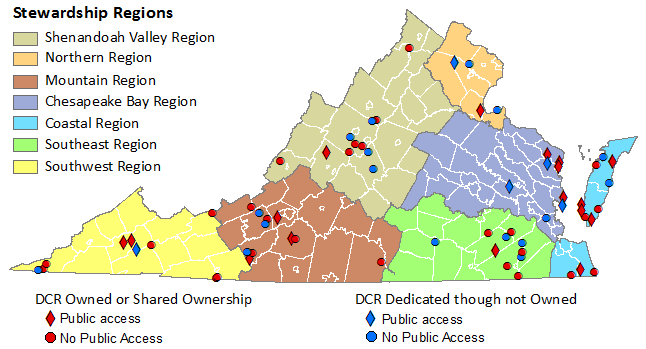

The interagency Wildlife Action Plan completed in 2015 identified 883 "Species of Greatest Conservation Need." The Natural Heritge Program in the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) manages over sixty units in the Virginia Natural Area Preserves System to protect Viginia's rarest natural communities and rare species habitats. Some preserves are open for public visitation, while some are restricted to minimize impact to sensive habitats.

species of special concern are protected in over 60 Natural Area Preserves

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Virginia Natural Area Preserves

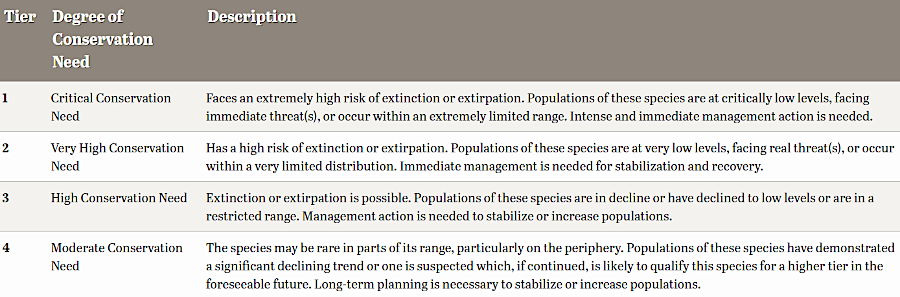

The Virginia Department of Wildlfe Resources is responsible for "conserving and managing Virginia's wildlife populations and habitat for the benefit of present and future generations." The state agency is funded through the sale of fishing/hunting licenses and boat registration fees and focuses most attention on game species, particularly fish, ducks, deer, and turkeys. Virginia Department of Wildlfe Resources reported in 2024:6

to prioritize resources dedicated to non-game species, the Wildlife Action Plan identifies four tiers of Species of Greatest Conservation Need

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR), Wildlife Action Plan (2015)

Southwest Virginia is the state's biodiversity "hot spot." Since the Alleghenian Orogeny 250 million years ago, the surface has eroded but not been covered by an ice sheet. That has allowed

ants "farm" aphids

Source: Judy Gallagher, Ants tending aphids, Julie Metz Wetlands, Woodbridge, Virginia

bluebells are spring ephemerals, flowering before trees leaf out and shade the forest floor

mural at George Mason University's Potomac Science Center (Prince William County)

pawpaw in bloom, Merrimac Farm Wildlife Management Area (Prince William County) |

beaver activity, Sweet Briar College (Amherst County) |

box turtle, Fairfax Villa Park (Fairfax County) |