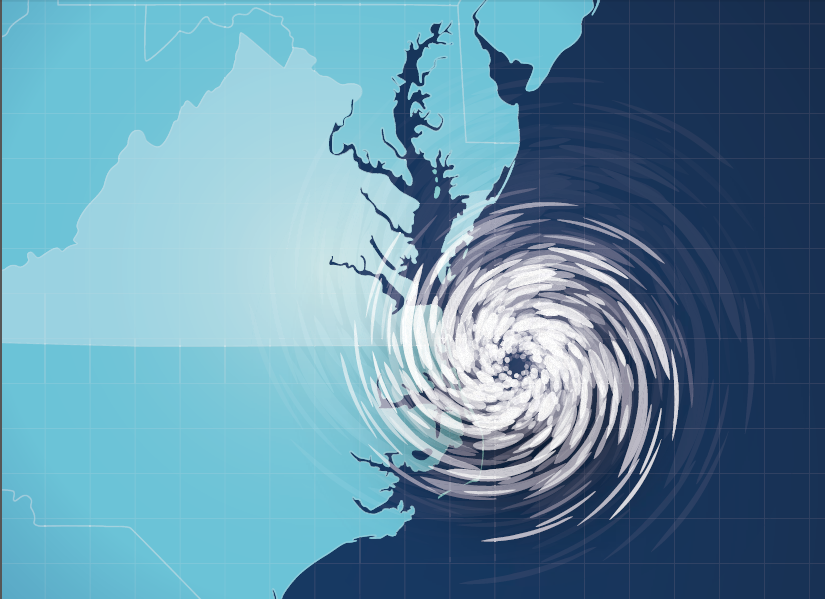

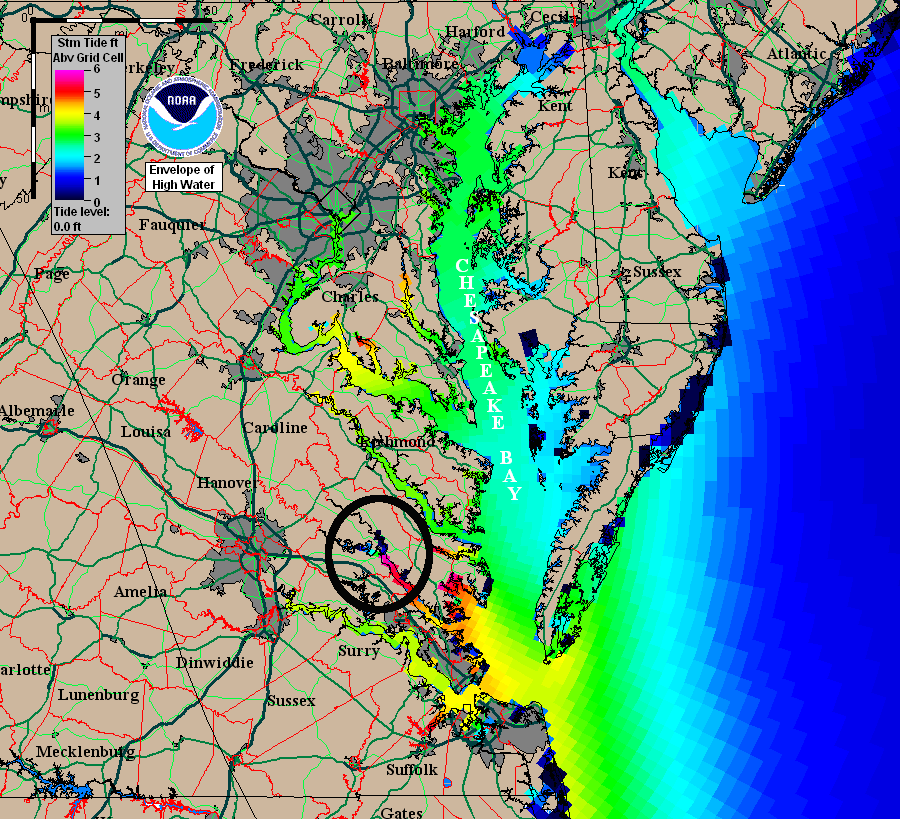

if a Class 3 hurricane pushed a storm surge into Chesapeake Bay at high tide, flooding in Hampton Roads would be massive

Source: Virginia Department of Emergency Management, Virginia Hurricane Evacuation Guide

if a Class 3 hurricane pushed a storm surge into Chesapeake Bay at high tide, flooding in Hampton Roads would be massive

Source: Virginia Department of Emergency Management, Virginia Hurricane Evacuation Guide

Hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean are generated by temperature differences between parts of the atmosphere, exacerbated by warm ocean waters. Instability in the atmosphere in North Africa evolves into swirling air currents over the ocean in tropical latitudes. Tropical storms can intensify into Category 1-Category 5 hurricanes on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale as they approach the West Indies in the Caribbean.

By definition, storms must have maximum sustained surface winds of 74 mph or greater to be categorized as a "hurricane." As the air and water vapor in a hurricane cool, wind speeds drop. Storms decline in intensity from hurricane to "tropical storm" (maximum sustained surface winds ranging from 39-73 mph) and further down to "tropical depression" (maximum sustained surface winds of 38 mph or less).

When Spanish ships first reached the Caribbean islands, they encountered the Taino and considered them to be "Indians." The Taino believed that one of the original gods who created the Earth was Huracan, also known as Hunraken or Jurakan. He became jealous of the creation made by his brother Yucaju and chose to destroy things as a powerful wind. That belief provided the name for the storms known today as hurricanes.

The National Weather Service assigns a name after a tropical depression grows to become a tropical storm. If intensity increases further, the same name is used for the hurricane. For example, in 2024 Tropical Storm Helene grew into Hurricane Helene. As it moved inland and winds slowed down, it returned again to being Tropical Storm Helene (or "remnants of Hurricane Helene" in weather reports) before finally dispersing.

The heavy rainfall caused massive flooding and landslides in western North Carolina. In Virginia, Washington County was most impacted. The upper half of the Virginia Creeper Trail was destroyed, with repair costs estimated at $200-300 million. A 1.5 mile section of Route 58 was washed out and the road was closed for nearly eight months.

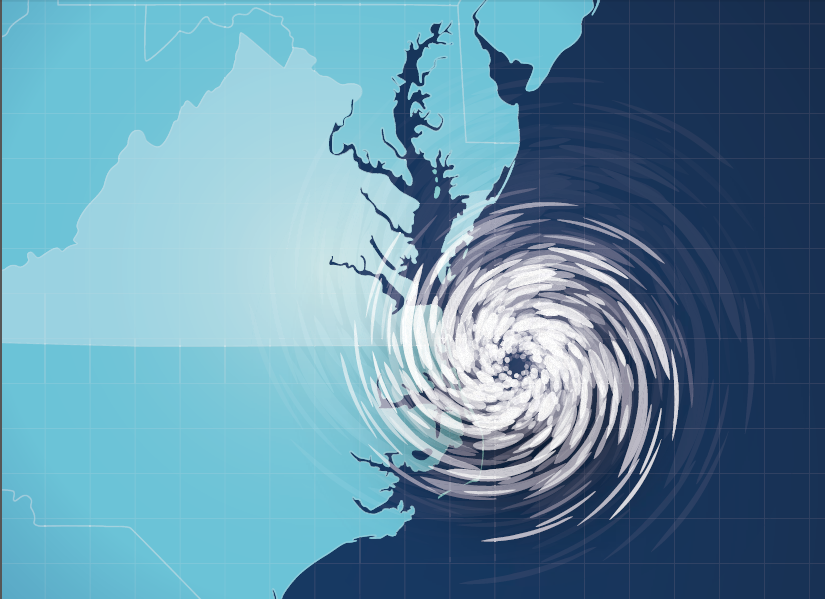

Hurricane Florence formed as a storm initially near North Africa, then migrated west and crossed the southwestern tip of Virginia

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Historical Hurricane Tracks

Some storms move north along the east coast of North America, following the Gulf Stream. As storms move to a higher latitude, they encounter cooler water. A hurricane which crosses the shoreline and travels across land no longer derives energy from warm ocean water and will decline in intensity.

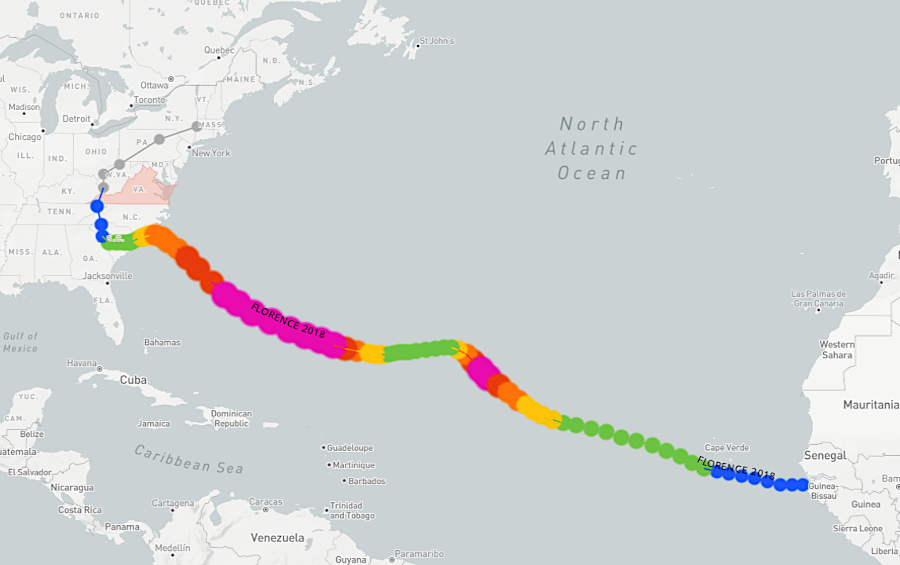

Virginia is unlikely to be struck by a Category 3 storm, because intensity drops as storms move into cooler latitudes

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale

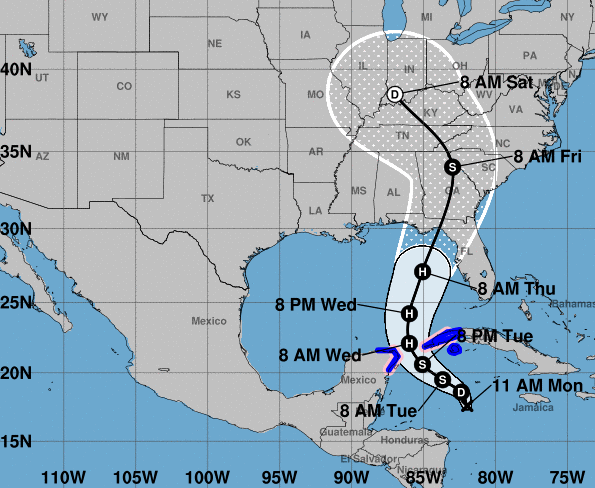

As sea temperatures rise, more energy can be transferred into storms. As water evaporates into the atmosphere, hurricanes can increase quickly in intensity - especially those passing over the Gulf of Mexico. That can further complicate the challenge of weather forecasters and disaster management officials to recommend where residents should plan to evacuate.

In the words of one climate scientist:1

When the Bermuda High is relatively small and located westward of its average position, tropical storms develop around the Cape Verde islands. Clockwise winds from the Bermuda High steer Cape Verde hurricanes into the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. Hurricane Melissa in 2025, which devastated Jamaica before passing across Cuba, was a Cape Verde hurricane.

If the Bermuda high is located to the east, the clockwise winds of the Bermuda High push hurricanes northward through the Atlantic Ocean on tracks that are east of the North American shoreline. Some hurricanes may come ashore in the Carolinas before moving north into the middle of Virginia. Occasionally a hurricane will bend eastward, leaving the route of the Gulf Stream and moving inland into New York or New England.

Climate change may have produced an eastward shift in the location of the Bermuda high 600-800 years ago, or a southward shift of the warm water in the Loop Current within the Gulf of Mexico. That may have lowered the number of hurricanes striking the Gulf Coast since European colonization, and increased the number that strike the East Coast.

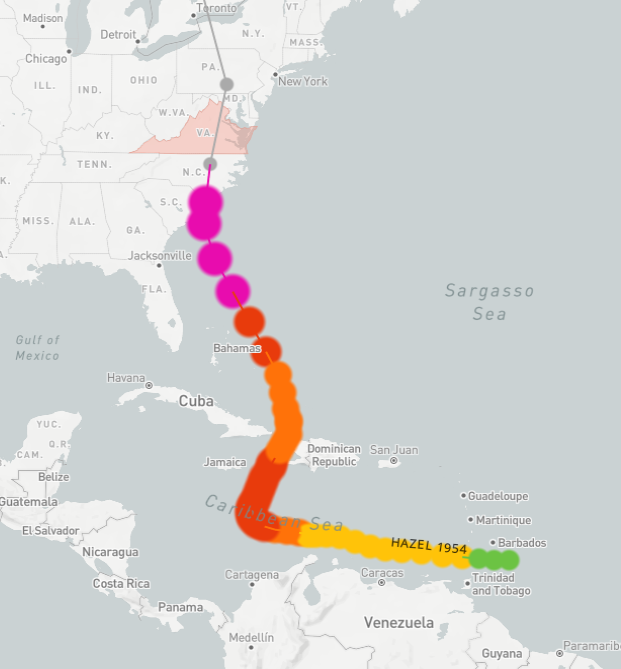

Hurricane Hazel reached hurricane strength while in the Caribbean, and declined in intensity to a low pressure system by the time it reached Virginia

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Historical Hurricane Tracks

Few hurricanes come inland ("make landfall") on Virginia's Atlantic Ocean shoreline. As a result, hurricane-related flooding events are most common west of the Fall Line in Northern Virginia, the Piedmont and the Blue Ridge - not on the Coastal Plain.

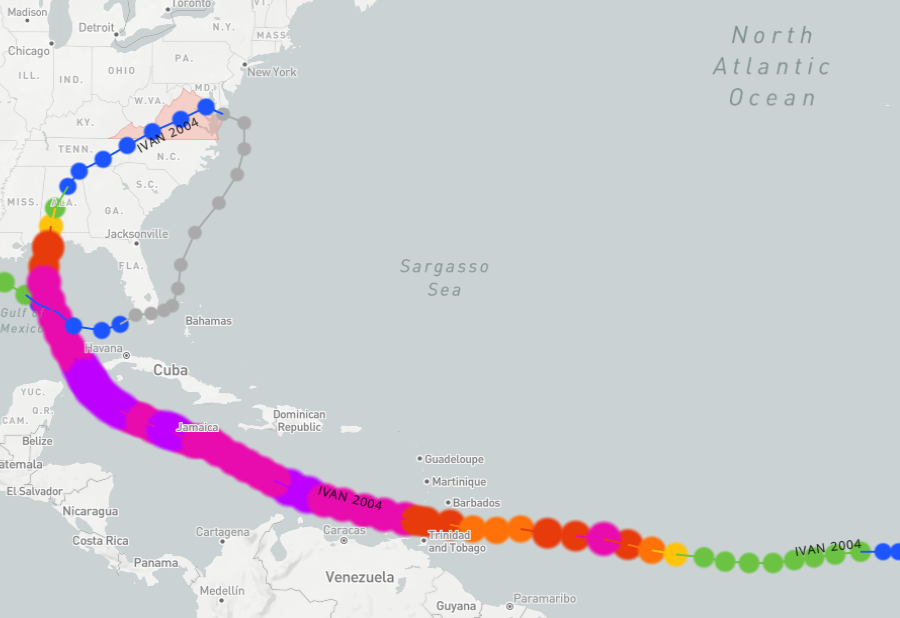

Hurricane Ivan passed through the Gulf of Mexico before moving through Virginia (then looped back to the Gulf on an unusual track)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Historical Hurricane Tracks

When the Bermuda High migrates to its western location, Atlantic Ocean hurricanes that cross into the Gulf of Mexico (rather than follow the Gulf Stream north along the eastern edge of North America to Cape Hatteras) can keep moving westward onto land in Central America or Mexico. However, most hurricanes that reach the Gulf of Mexico turn north to hit the United States between Galveston and Tallahassee.

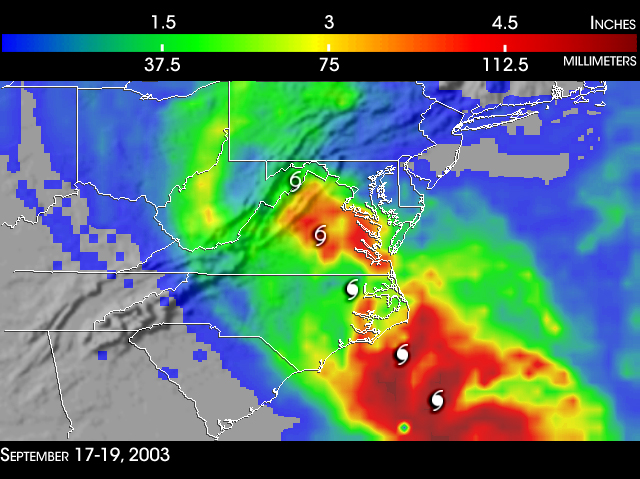

Typical storm tracks bring those storms across the Appalachians and back to the Atlantic Ocean. Wind speeds drop as the storms pass over the land and lose the heat from warm water, but tropical storms that reach Virginia can be loaded with enough moisture that they cause dramatic flooding and damage along the Blue Ridge.

The biggest such killer storm in modern times was Hurricane Camille in 1969, which triggered an extraordinary number of landslides centered in Nelson County. Remnants of Hurricane Helene in September 2024 created intense rainfall that devastated western North Carolina and impacted Southwest Virginia towns such as Damascus, Marion, Pembroke, Pearisburg and Narrows.

rainfall from Hurricane Helene in 2024 caused massive flooding in western North Carolina and Southwest Virginia - far from the Atlantic Ocean shoreline

Source: National Weather Service, September 26-30, 2024 Hurricane Helene

houses in Damascus were flooded and washed away by the 4-6 inches on rain from Hurricane Helene in 2024

Source: Ben Earp, October 2 Facebook post

Portions of the Appalachian Trail in Virginia were closed until December 13. On the eastern half of the Virginia Creeper Trail extending from Whitetop Station near the North Carolina border to Damascus, 18 of the 32 trestles were destroyed and 13 others were damaged by floodwaters racing down Whitetop Laurel Creek. US 58 was also washed out near Damascus, complicating the ability to move materials needed for trail restoration. The economy of Damascus, a town of less than 800 residents that is called Trail Town USA, depended upon the 200,000 tourists who came each year to bike and hike the Virginia Creeper.

A ranger for the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area said:2

debris on Virginia Creeper Trail Trestle 19, after Hurricane Helene

Source: US Forest Service, Hurricane Helene Information - Virginia Creeper Trail

The normal flow of the New River as it reaches Claytor Lake is 3,000 cubic feet per second. In Helene, flow reached 167,000 feet per second. Firefighters heard metal screams when trailers along the river were washed off their foundations and slammed into trees and other debris. One of the 100 propane tanks removed from the lake came from West Jefferson, North Carolina.

The Pulaski County Administrator said that before the hazardous propane tanks were extracted from the lake:3

A cabin in Allisonia was washed off its foundation, carried underneath a low-water bridge, and deposited somehow largely intact on the shoreline 20 miles downstream. Flooding impacted 240 properties along Claytor Lake, causing around $35 million in damage.

trailers along the New River in Giles County were flooded by remnants of Hurricane Helene in 2024

Source: State Senator Travis Hackworth, Facebook post (September 29, 2024)

Behind the dam, Claytor Lake was cluttered by a 20-acre floating debris field that included propane tanks, appliances, former boat docks, and scraps of wood which were once structures upstream. Claytor Lake was closed to boating except for clean-up crews, who had to maneuver carefully so propellers would not be damaged by floating and underwater debris.

after Hurricane Helene, Claytor Lake collected debris washed down from structures that were destroyed by upstream flooding

Source: Brian Garrett, Another video of Helene's mess on Claytor lake

On September 28, 2024 the National Park Service closed down the entire 469-mile Blue Ridge Parkway from Rockfish Gap in Virginia to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee to assess damage, clear fallen trees, and make repairs to pavement. The stretch from Milepost 0 at Rockfish Gap to Milepost 198 in Carroll County reopened on October 10. It took an extra week to reopen the stretch to the North Carolina state line at Milepost 217.

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy reported after Helene:4

United States Coast Guard Auxiliary volunteers, including Virginia Tech students, helped clear debris from Claytor Lake brought down the New River by rainfall from Hurricane Helene

Source: Virginia Tech, Students help with disaster relief at Claytor Lake (October 2, 2024)

Hurricanes affected Native Americans living near the Chesapeake Bay before colonization, but there are no records documenting storms or their impacts on people living in Powhatan's paramount chiefdom or other parts of what we now call Virginia.

There are records of major storms after permanent colonization started in 1607. A hurricane almost ended English settlement at Jamestown just two years after it began.

In 1609, the Third Supply fleet sailed from England and ran into a storm near Bermuda. The flagship Sea Venture with Sir Thomas Gates, who had been appointed by the Virginia Company to serve temporarily as governor in Jamestown, crashed onto the reef at Bermuda. All on the ship survived the wreck, but the Jamestown colonists experienced the Starving Time of 1609-10 under the inept leadership of George Percy while the new officials were marooned on an island in the Atlantic Ocean.

When Sir Thomas Gates finally reached Jamestown in 1610, after building two new ships on Bermuda, he quickly concluded the colony could not survive and ordered everyone to sail back to England. A storm that had started off the coast of northern Africa could have made Jamestown a ghost town. Only the timely arrival of Lord De La Warre, with additional supplies and colonists, kept the English colony going in Virginia.

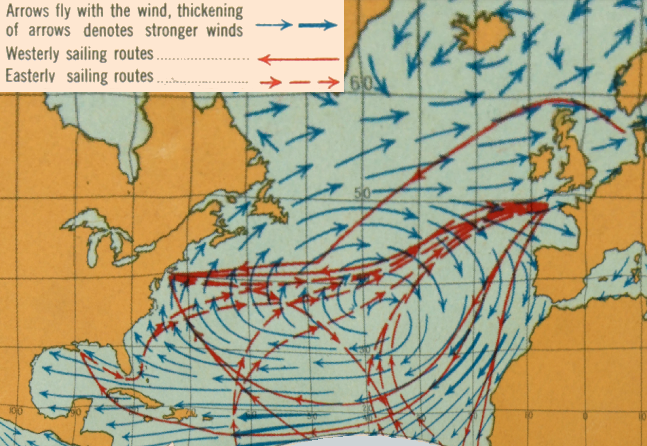

the most-direct route from England to Virginia required tacking against westerly winds, so ships often sailed south to the Azores and then west across the Atlantic Ocean following the same track as hurricanes

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Winds and Sailing Routes: Summer (Plate 1e, digitized by University of Richmond)

The 1609 hurricane which affected the colony occurred far at sea and south of Virginia. Three 1780 hurricanes in the Caribbean shaped the American victory at Yorktown in 1781.

Until those hurricanes, the French had been unwilling to send their Caribbean fleet north to assist George Washington and the rebelling colonists. Protecting the sugar-producing islands was a priority. After the near-destruction of the Spanish fleet during one of the 1780 hurricanes, the French chose to preserve their ships by sailing out of the Caribbean during the 1781 storm season.

That decision by the French Navy enabled George Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau to craft a combined sea and land attack on Lord Cornwallis's army. The French fleet won the Battle of the Capes, blocking the British Navy's effort to resupply and support Cornwallis.

That allowed the siege to continue, forcing the British surrender at Yorktown and leading to American independence. A strong gale near the end of the siege also helped, since that storm prevented Cornwallis from transporting his army in barges across the York River and escaping north.5

Cornwallis's few ships were trapped, along with his army, when the French Navy avoided Caribbean hurricanes and sailed to the Chesapeake Bay in 1781

Source: Library of Congress, plan of the investment of York and Gloucester (by Sebastian Bauman, 1782)

Only a handful of storms have reached the land of the United States as strong Class 5 hurricanes as defined by the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, based on maximum sustained (1-minute) surface (10 meter) winds produced at the coast. Class 5 hurricanes making landfall since the 1850's in the United States include the Labor Day Hurricane (1935), Camille (1968), Andrew (1992), and Michael (1992).

Virginia rarely experiences even Class 2 hurricanes because of its position on the globe north of 36° 30' latitude. Hurricanes moving north of the Carolinas encounter cooler water at higher latitudes, with less energy to support a storm. The wind intensity drops as the temperature of the ocean drops, so the category on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is diminished.

Puerto Rico, Caribbean islands, Florida and Louisiana get struck on occasion by Class 5 hurricanes. South Carolina gets hit by Class 4 hurricanes, including Hurricane Hugo which devastated the state in 1989. Hurricane Katrina, which flooded New Orleans in 2005, was a Class 3 hurricane when it reached the Louisiana coast.

As the ocean warms over the next century, Class 3 hurricanes could make landfall further north and a Category 6 might be needed on the existing scale. The most likely "worst case scenario" for a hurricane striking Virginia is for a Class 3 storm to make landfall at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Winds at the mouth of the bay will push a storm surge of water inland and flood places such as Norfolk.

Atlantic coastline hurricanes typically make landfall south of Virginia, moving ashore in South Carolina and North Carolina. Other storms stay offshore, following the Gulf Stream north. Because low pressure systems have winds moving counter-clockwise, impacts moving north to Hampton Roads along the coastline often start with winds from the northeast. Wind direction shifts as the storm moves north, depending upon whether the center passes to the east or west of Hampton Roads.

According to a report of a 1667 storm that passed east of Jamestown:6

hurricane winds flow in a counter-clockwise direction, so storms moving north along the Virginia coast start by bringing moisture inland from the ocean

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Hurricanes

On July 24, 1788, George Washington recorded the wind pattern from the hurricane that passed over Mount Vernon the previous day:7

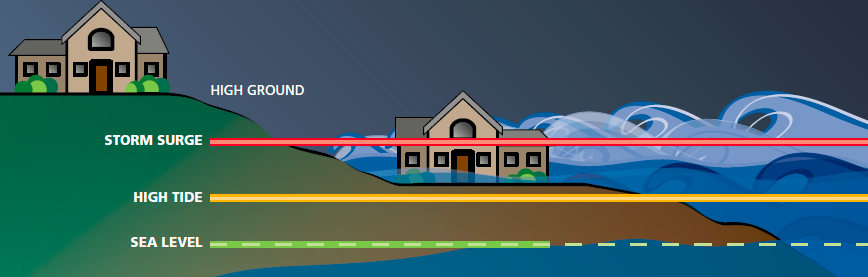

The wind from hurricanes offers some danger wherever a storm passes through Virginia, and intense one-day rainfall events in the Blue Ridge reshape stream channels and trigger landslides. On the coastline, flooding from the storm surge is the greatest danger. The 1667 hurricane may have brought the strongest winds to strike the Virginia coast in recorded history, but not the highest water levels.

The water level in the Chesapeake Bay apparently rose 12 feet in 1667, but in 1749 another storm created a 15-foot high storm surge. The floodwaters in that storm pushed enough sand out of the Chesapeake Bay to create the initial Willoughby Spit, which was enlarged to current dimensions by the "Great Coastal Hurricane of 1806."

Willoughby Spit was formed primarily by two hurricanes in 1749 and 1806

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

There was a significant hurricane in 1769, the "Independence Hurricane" in 1775, and "George Washington's Hurricane" on July 23, 1788.

Major storms in the 1800's include the Great Coastal Hurricane of 1806 and an 1821 hurricane whose eye passed directly over Norfolk.

The September 3-4, 1821 hurricane is known as the Great September Gust, or the 1821 Norfolk Long Island Hurricane. After making landfall on the Outer Banks of North Carolina as a Category 4 hurricane, it weakened only gradually as it moved north. It had 100 miles/hour winds as it crossed over the Eastern Shore.

The 1821 hurricane completely flooded Chincoteague Island, perhaps after triggering a landslide on the continental slope and causing a tsunami. No houses survived on the island; the oldest structures on Chincoteague today were built as replacement houses after the 1821 storm.

The eye of the "Great Tempest" of 1879 was 50 miles west of the city. That storm triggered a high tide eight feet higher than normal.

An eight-foot high storm surge today would devastate downtown Norfolk and the US Navy's largest base, but even worse is possible. When Hurricane Michael hit Florida in 2018, that Class 4 hurricane brought a storm surge over 15 feet high. The waves were another four feet higher, so water in that storm reached up to the height of a two-story building.

Significant hurricanes in the 1900's include a 1903 storm that killed hundreds of small birds at Old Point Comfort, stripping their feathers while in flight and causing a deluge of carcasses falling out of the sky.

The eye of the August 23, 1933 Chesapeake-Potomac Hurricane also passed directly over Norfolk, resulting in one of the lowest barometric pressures (28.68") ever recorded in Virginia. The storm paralyzed Tidewater, after a surge of water as much as nine feet high moved up the Chesapeake Bay. The storm surge flooded a cottage on 55th Street in Virginia Beach, but the father took a door torn off its hinges and made a raft to float his family and their dog to safety.

On the south bank of the James River opposite Jamestown, the pier for the Surry-Jamestown Ferry was destroyed. At Colonial Beach, the amusement park washed away. Three feet of water covered the Washington-Hoover airport at the current site of the Pentagon. North of Chincoteague, the storm cut through Assateague Island and created the Ocean City inlet.

Source: Australian Government - Bureau of Meteorology, Understanding Storm Surge

The 1935 Labor Day Hurricane which devastated the Florida Keys moved north into Virginia. It was a much-diminished storm when it moved back into the Atlantic Ocean near the North Carolina/Virginia border, but still powerful enough to spawn a tornado in Portsmouth. Many other hurricanes that move into Virginia as tropical storms have also caused tornadoes, so wind damage remains a serious threat even as hurricanes are fading.

Hurricane Hazel in 1954 passed west of National Airport in Arlington County, bring 98mph wind gusts. Remnants of that hurricane demonstrated how storm impacts can occur across the state, and not just along the coast. In the Shenandoah Valley, 150,000-250,000 turkeys died when the storm knocked down poultry sheds.

In 1955, Hurricane Diane brought 5-10" of rain to the slopes of the Blue Ridge, creating flash floods. Hurricane Michael (in 2018) dropped 9" of rain on Danville in just 90 minutes, and the record-setting rise in the Dan River turned the flood plain into a lake.8

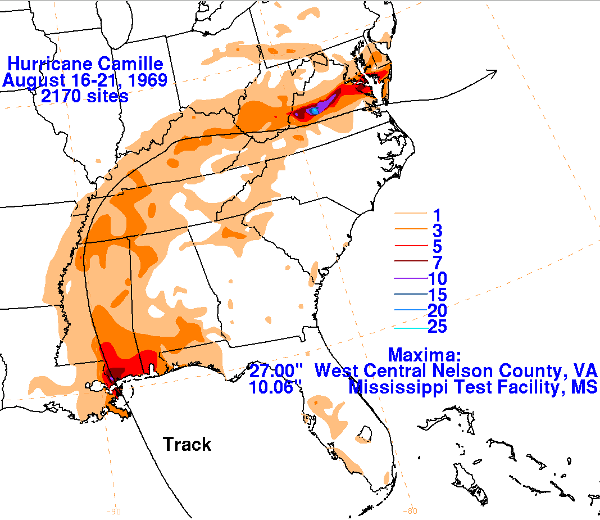

On the evening of August 19-20, 1969, the residue of Hurricane Camille stalled over the Blue Ridge in Nelson County. The winds of the storm had slowed down and it was no longer classified as a hurricane, but the clouds were still of moisture. Air currents and topography kept Camille overnight in Nelson County. Multiple storm cells formed in the thunderstorm complex at essentially one place, and together they dropped as much as 30" of rain in just eight hours.

The water over-saturated the hillsides and liquified the soil, causing landslides that crashed into the valley of Davis Creek and other tributaries of the Tye and Rockfish rivers. At least 113 people died, and debris scars or "chutes" on the slopes are still visible today.

in 1969, Hurricane Camille dropped at least 27" of rain overnight in Nelson County

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Hurricane Camille - August 16-21, 1969

One effect of that storm is that emergency managers began to plan for the risks of hurricane damage that might occur far from the Atlantic Ocean. The winds and storm surge, the rise in sea level associated with the lower barometric pressure in the eye of the hurricane, is only one of the threats. Hurricanes can cause falling trees, landslides, loss of electricity and drinking water, and disruption of the transportation network within the Appalachian Plateau, the Valley and Ridge Province, the Blue Ridge, and the Piedmont as well as on the Coastal Plain.

Geologists and hydrologists also realized after Hurricane Camille that such major storms occur every 500-1,000 years in the watersheds of the Blue Ridge. Such massive rainstorms are rare events, but occur frequently enough to be a key factor in shaping the morphology of the Blue Ridge.

Topographic change is a process of "punctuated evolution" as well as gradual change. In just a minutes, big storms can transform the landscape more significantly than centuries of slow erosion. The 1969 storm and a 1995 flash flood in Madison County revealed that much of the carving of stream valleys, and much of the lowering of Virginia's mountains, occurs in short bursts during major storm events more than from annual slow erosion. Intermittent punctuated evolution, rather than steady change, shapes the landscape.9

Hurricane Agnes created massive flooding to Central Virginia in 1972. Floodwaters flowing over the top of the two dams on the Occoquan River destroyed the Route 123 bridge at the Town of Occoquan, plus one of the Route 1 bridges downstream.

the Route 123 bridge destroyed in Hurricane Agnes, 1972

Source: Library of Virginia, Raging Occoquan River

the Route 1 bridge over the Occoquan River, destroyed by remnants of Hurricane Agnes in 1972

Source: Library of Virginia, Repairs begin at Occoquan Bridge

In 1996, Hurricane Fran brought 16 inches of rain to Big Meadows and downed trees across Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park. The park was closed for two weeks.

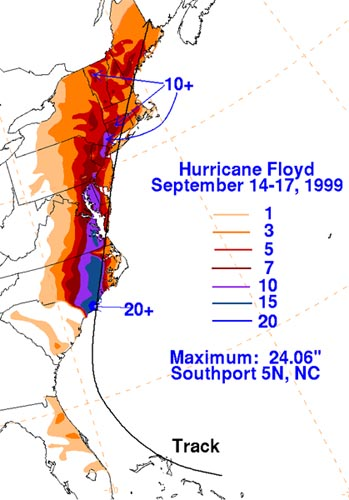

In September, 1999, the remains of Hurricane Floyd dropped 15" of rain within 24 hours in Southeast Virginia. Runoff caused the Blackwater River to rise and inundate the Town of Zuni and the City of Franklin. From Florida to Virginia, an estimated 3,000,000 people tried to drive away from the storm. The traffic jam is legendary for emergency managers, and spurred planning in Virginia to avoid a repeat of that congestion if the governor orders an evacuation.10

extraordinary rainfall from Hurricane Floyd created flooding in Zuni and Franklin

Source: National Weather Service, Hurricane Floyd Storm Summary

Massive rainfall from a storm can overwhelm the stormwater management systems in urbanized areas, as Hurricane Floyd demonstrated in 1999 when it swamped the city of Franklin and tropical storm Gaston did to Richmond's Shockoe Valley in 2004. In 2003, winds from Hurricane Isabel wrecked utility systems throughout the Coastal Plain of Virginia, leaving some people without electricity for two weeks.

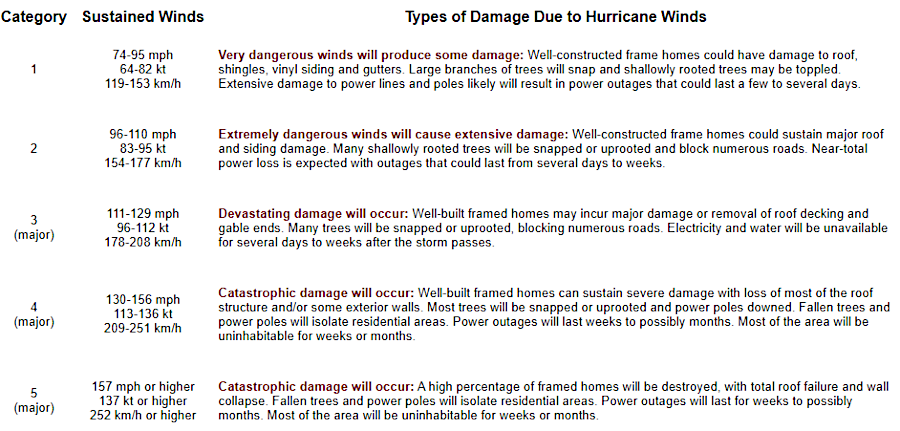

storm surge can be as much as 15 feet higher than high tide

Source: Virginia Department of Emergency Management, Virginia Hurricane Evacuation Guide

If a hurricane brings a storm surge of 6-8 feet to Virginia's coastline, the damage will be measured in billions of dollars. Much of Virginia Beach, Portsmouth, Hampton and Norfolk will be underwater due to the storm surge.

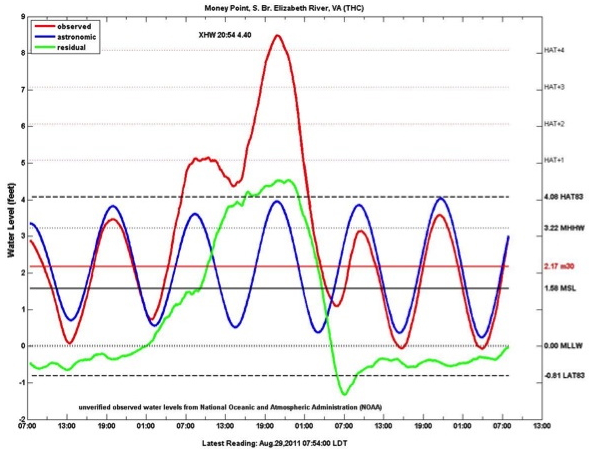

Hurricane Irene was a Class I storm when it passed through Hampton Roads in 2011 and created 3.5-foot to 4.5-foot storm surges. State officials were relieved that the potential 8-foot surges predicted by some models did not occur. Local residents complained that impacts of the flooding were exacerbated by sightseers in trucks with jacked-up suspensions, The trucks created wakes that pushed water inches higher, into houses that otherwise might have stayed dry.11

observed water levels (red), predicted astronomic tide (blue), and the 4.4-foot storm surge (green) at Money Point in Portsmouth during Hurricane Irene

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Hurricane Irene Storm Tides

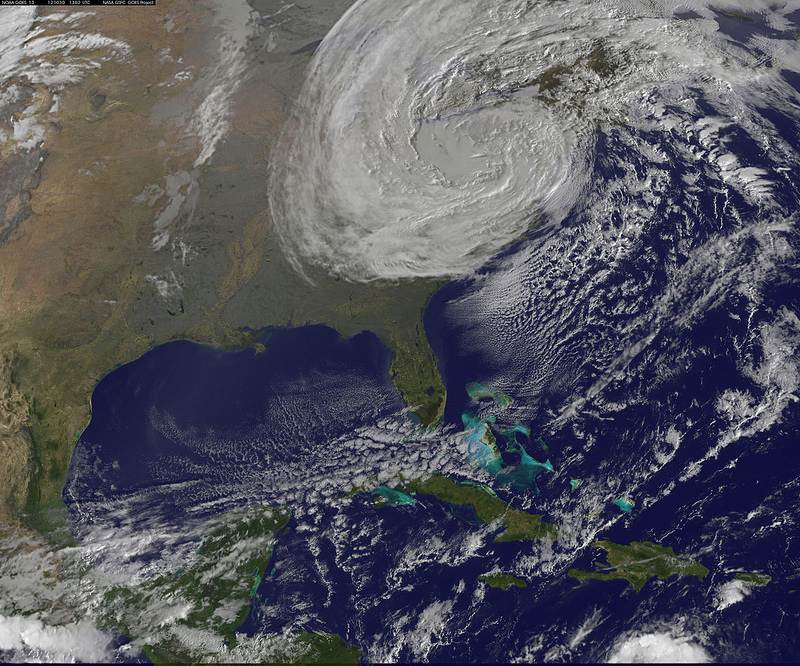

Superstorm Sandy in October, 2012 bypassed most of Virginia before slamming into New Jersey and New York City, but a future storm like it could redistribute the sands on Willoughby Spit and destroy all the development and the southern end of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel. A Class 3 hurricane will hit the Chesapeake Bay someday, and coastal cities are preparing for the inevitable.

Models are just one tool used to predict hurricane paths and intensity. Forecasters, not computers, make forecasts using satellite data, previous hurricane history, and assessments of a changing climate as the oceans get warmer.

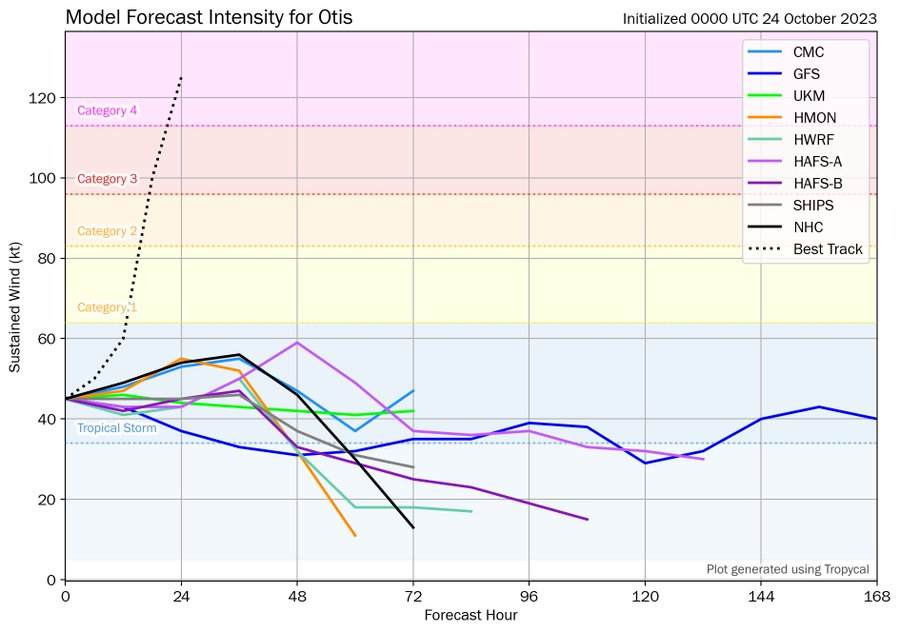

Models have been particularly poor at anticipating when a storm will intensify rapidly, though in 2023 they did alert forecasters that Hurricane Idalia would grow in intensity quickly before slamming into the west coast of Florida. Later in 2023, models completely missed the extraordinary growth within one day of Tropical Storm Otis into Class 5 Hurricane Otis before it hit the west coast of Mexico.

computer models failed to predict the rapid intensification of Hurricane Otis from tropical storm to Class 5 hurricane within one day

Source: Twitter, Tomer Burg (October 24, 2023)

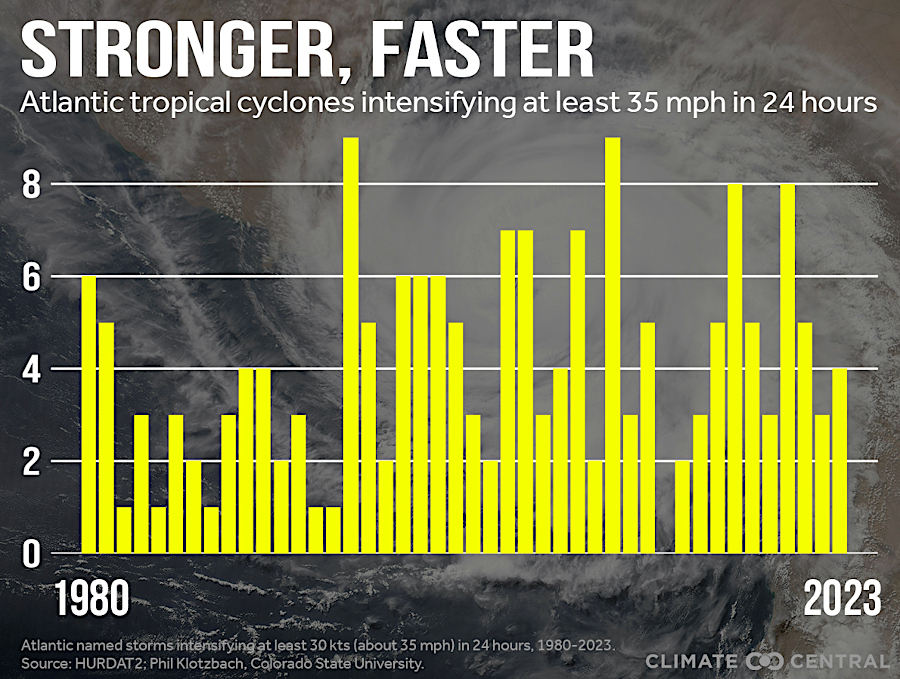

warmer sea temperatures facilitate faster increases in hurricane intensity

Source: Climate Central, Rapid Intensification

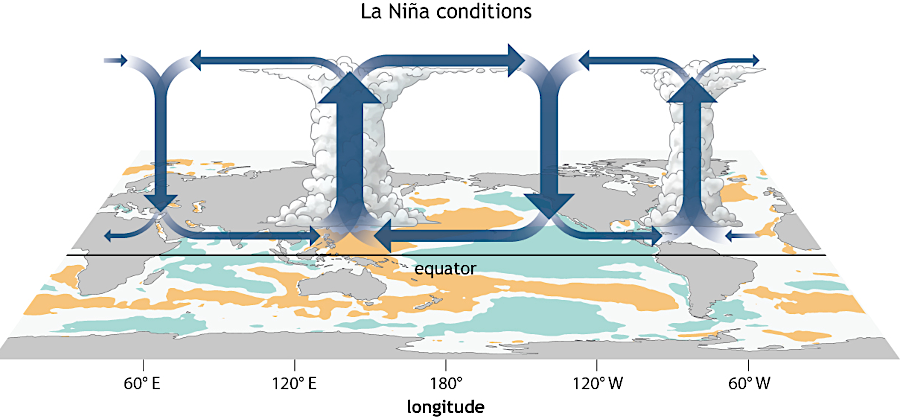

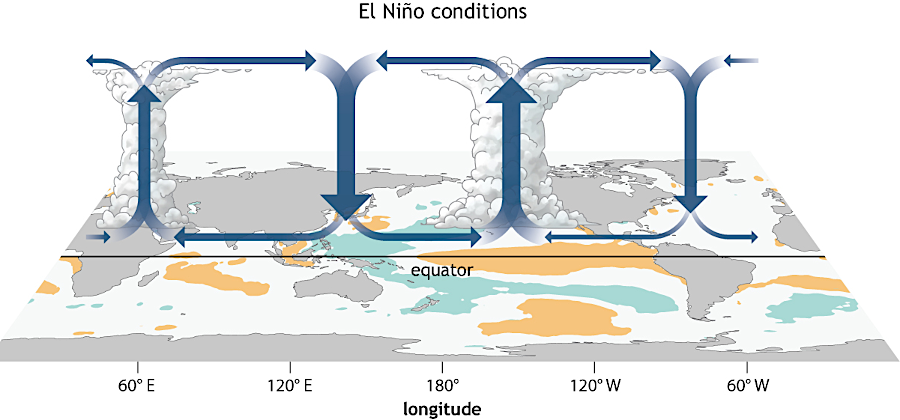

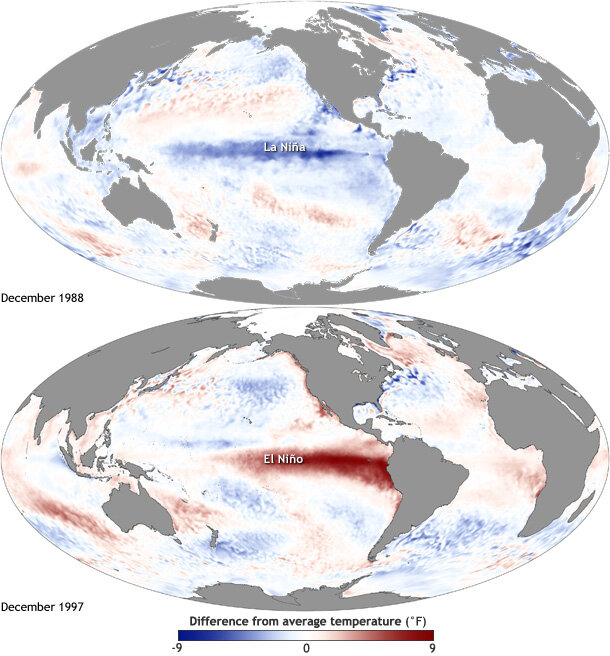

The El Niño and La Niña climate oscillations affect the number of hurricanes that form and may strike Virginia. In the La Niña phase, Pacific Ocean waters off the coast of Peru are cooler than average. In an El Niño event, the ocean warms up by 0.5° Celsius (0.9° Fahrenheit) or more.

Source: NOAA Climate, Understanding El Nino

The temperature differences in the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events affect the circulation patterns of tropical air masses that dissipate the heat in the Pacific Ocean water, a wind pattern called the Walker Circulation. Warm air rises from the western side of the Pacific Ocean near China, flows eastward, and sinks back to the surface on the eastern end near North America. That creates easterly winds at the surface of the ocean.

During El Niño ocean conditions, the intensity of air flow is less. During La Niña ocean conditions, the Walker Circulation is stronger and easterly surface winds are stronger.

changes in the Walker Circulation above the Pacific Ocean affect the flow of air over North America

Source: Climate.gov, The Walker Circulation: ENSO's atmospheric buddy

The jet stream, the major air current across North America, moves further south in an El Niño event. That increases wind shear over the Atlantic Ocean and disrupts rising air currents that otherwise would form hurricanes. During a La Niña event, wind shear is impacted less and weather forecasters predict that more hurricanes will form.

climate oscillations in the Pacific Ocean affect the jet stream, causing more hurricanes to form in the La Niña phase

Source: Climate.gov, What is the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in a nutshell?

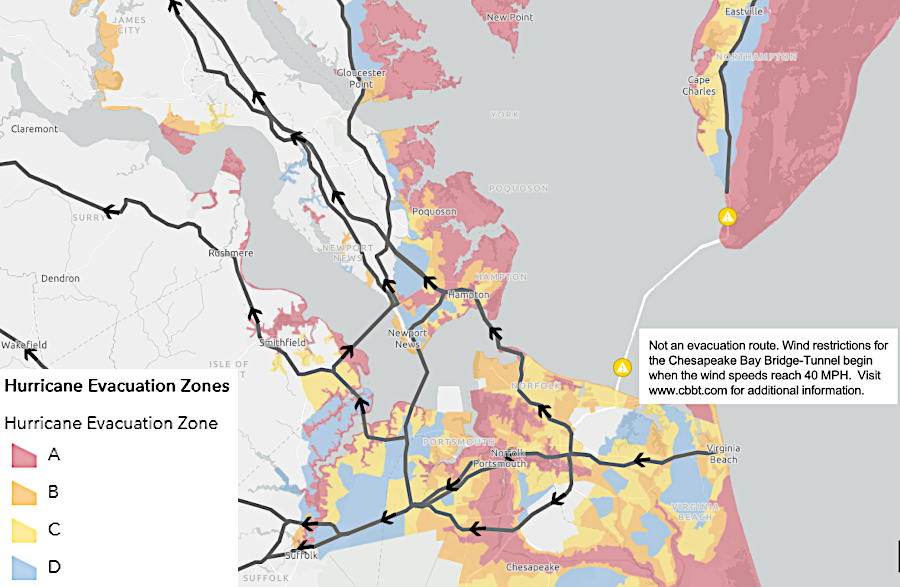

The Virginia Department of Emergency Management (VDEM) has identified areas near the Chesapeake Bay with the highest risk of being isolated and flooded when a hurricane passes through Virginia. Four evacuation zones have been designated. While topography and road elevations are static, predictions of storm surge and rainfall are judgement calls for each storm. Television, radio, and social media messages announce when residents in Zone A should leave first, since that is the highest risk area.

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel is *not* a designated evacuation route for residents fleeing in advance of a hurricane

Source: Virginia Department of Emergency Management (VDEM), Know Your Zone

The path of a hurricane as it moves along the Chesapeake Bay can make a major difference on how people and infrastructure will be affected:12

Awareness of the flooding risk is increased by local efforts to document the "king tide," the highest tide predicted each year based on the alignments of the sun and moon. As described by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS):13

During the king tide, the moon's orbit brings it closest to the earth for that year. Gravitational forces can push the normal high tide water levels as much as two feet higher. Volunteers use the SeaLevelRise app on their smart phones to help the Virginia Institute of Marine Science refine its models of which areas will flood. Citizen reports might reveal where culverts that are underwater only during a king tide, and not recorded in the LIDAR-based topographic layer in the model, can cause an area to flood unexpectedly.14

Source: YouTube, Sea Level Rise App - A Mapping Event

The Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) has even considered building a 24-mile long barrier at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, parallel to the bridge-tunnel, to block storm surges. The first step was to create computer models to assess potential designs and environmental impacts. The academic exercise requires making no decisions; the tough choices regarding costs vs. benefits (and how to ensure US Navy warships would never be trapped inside Hampton Roads) will come later.15

the storm surge from Hurricane Isabel was as high as six feet near West Point, on the York River

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Historical SLOSH Simulations - Isabel

A study in 2021 estimated how climate change would increase the impacts of weak and strong hurricanes in the Chesapeake Bay. Sea level rise and loss of wetlands were predicted to result in substantially greater property damage, even if storm intensity remained unchanged. Flooding from low intensity hurricanes, the most common type to hit Virginia, in particular would increase:16

Global warming has added heat to the oceans; five hurricanes between 2012-2021 developed wind speeds that exceeded 192 miles per hour. The top of the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale is open ended, so the most intense storms are still categorized as Category 5. To identify storms with the highest wind speed, climate scientists have proposed creating a Category 6. Under the new scale, Category 5 storms would have winds between 157-192 miles per hour and Category 6 storms would have winds exceeding 192 miles per hour.

Category 6 storms may not be the most dangerous or damaging hurricanes. Wind is a factor, but:17

Hurricane Isabel flooded homes along the Lafayette River in Norfolk

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), Norfolk Max. Flooding Extents during 2011 Hurricane Irene

An Old Dominion University study released in 2025 estimated that if a Category 3 hurricane made landfall at Hampton Roads, damages to physical infrastructure would reach $15 billion. The study used Hurricane Florence as a guide for assessing impacts of a storm dropping 36 inches of rain. That hurricane passed through eastern North Carolina in 2018, just south of Hampton Roads, and drpped 30 inches of rain there. A worst-case scenario assuming higher sea levels produced damage estimates exceeding $37 billion.

The most recent storm to strike Hampton Roads directly and similar to Hurricane Florence was the 1821 Norfolk-Long Island hurricane. The director of the Old Dominion University Dragas Center for Economic Analysis and Policy said:18

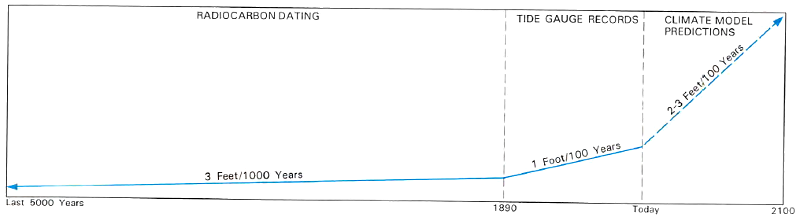

sea level rise predictions

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Vanishing Lands - Sea Level, Society, and Chesapeake Bay (Figure 10)

Superstorm Sandy in October, 2012 bypassed most of Virginia before slamming into New Jersey and New York City

Source: MSNBC

in 2024, Helene's heavy rainfall caused flooding in Whitetop Laurel Creek that obliterated portions of US 58

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR), A Post-Helene Update from the DWR Region 3 Fisheries

remnants of Hurricane Irene toppled large trees in Arlington County in 2011

Source: Arlington County, Barcroft Neighborhood

storms such as Hurricane Isabel create storm surges on the coast, and also generate enough concentrated rainfall to flood valleys in the Blue Ridge

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Earth Observatory, Hurricane Isabel

debris filled Claytor Lake after remnants of Hurricane Helene created extraordinarily heavy rainfall in North Carolina

Source: State Senator Travis Hackworth, Facebook post (September 29, 2024)