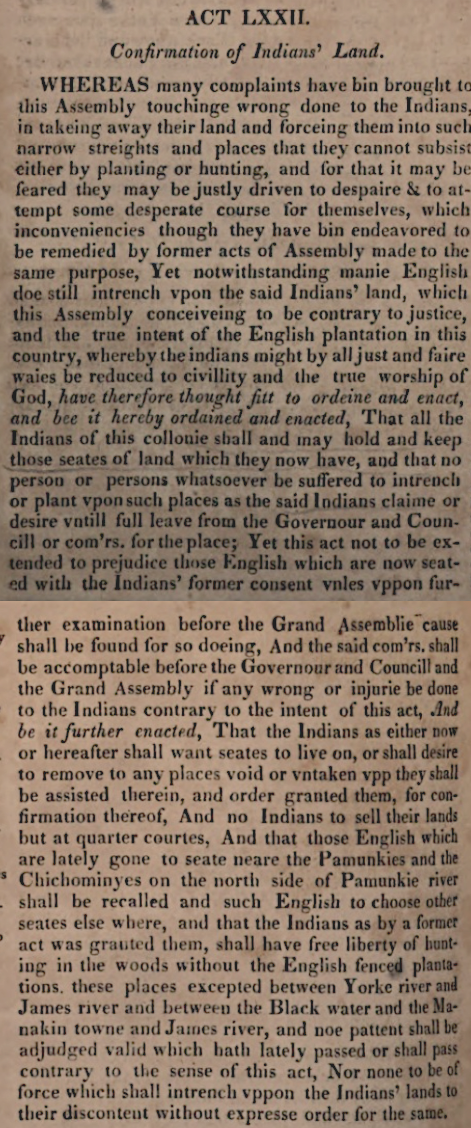

the Mattaponi Reservation on the Mattaponi River is on the opposite side of King William County from the Pamunkey Reservation on the Pamunkey River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Mattaponi Reservation on the Mattaponi River is on the opposite side of King William County from the Pamunkey Reservation on the Pamunkey River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Virginia has two state-recognized reservations, both located on tributaries of the York River. The land within those two reservations was first designated in the 17th Century as an area where the remnants of Powhatan's paramount chiefdom would retain control. The 1632 treaty which ended the Second Anglo-Powhatan War was the first of many efforts to separate the Native Americans from the English. Only a small remnant of the area designated for use by the Native American tribes ended up as part of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi reservations.

No Federal reservations for Native Americans have ever been created in Virginia, because no treaties were signed between Virginia's tribes and the Federal government to end a war. Reservations west of the Mississippi River were usually commitments of land made by the Federal government during treaty negotiations. After ratification of the US Constitution in 1788, Federal officials have had primacy for signing treaties with Native American and other nations. In those treaties, the US Government promised to cease fighting and to provide supplies, in exchange for promises by defeated Native American groups to move onto reservations.

The Third Anglo-Powhatan War in 1644-46 transformed relationships between the Virginia tribes and English colonists. The English won the war. In the Articles of Peace signed in 1646, the tribes accepted tributary status. They acknowledged that their land was subject to the authority of the King of England, they had to engage in trade with the English at locations defined in the treaty, and they had to move out of the Peninsula downstream of the Fall Line. The tribes were displaced from what became English-only territory, and the first geographic boundary was established between Native and non-Native lands.

The English were entitled to select successors to Necotowance, "King of the Indians," and the Native Americans were obliged:1

The 1646 treaty identified the York River as the boundary separating lands authorized for English settlement from the lands still controlled by the remanants of the paramount chiefdom under Necotowance. To travel on the Peninsula between the York and James rivers, east of the Fall Line, a Native American had to wear a specific silver badge. Isolating people in the two cultures was expected to minimize friction and incidents which might lead to new fighting.

A dozen years after the 1646 treaty, the General Assembly again sought to minimize conflicts with the Native Americans by limiting where colonists could settle. Long before King George III issued the Proclamation of 1763, which helped trigger the American Revolution, official policy was to reduce the potential of war by drawing boundaries that defined the territory reserved for just Native Americans.

In March, 1658 (1657 by the calendar in use at that time), Sir William Berkeley was living quietly at Green Spring and Samuel Mathews was the governor in Virginia. Berkeley had been deposed as governor when King Charles I was executed and England became a Commonwealth controlled by Parliament. However, the officials appointed by Parliament and by the king shared a common perspective: colonial settlement had to be constrained in order to avoid expensive conflict with the Native Americans.

The 1657/58 law banned land purchases by the English unless they had been approved by colonial officials; private deals with tribes, which were likely negotiated under threat of physical harm, were prohibited. The law stated that all the land not authorized for purchase was limited to occupation by just the Native Americans, and that specific parcels of land ("seates") would be reserved for them if requested:2

the General Assembly promised to set aside "seates" for tribes where they would not be disturbed by English settlers

Source: William Waller Hening, The Statutes At Large (Volume 1 March 1657/1658)

The last major military conflict involving Native Americans in Virginia occurred in Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, a century before the United States was created. The Treaty of Middle Plantation at the end of that conflict was signed in 1677 and expanded to include more tribes in 1680. Section III defined the colonial "land for peace" strategy:3

By the time the Articles of Confederation were ratified in 1781 and Virginia officially became part of new nation, various Native American groups in Virginia already had been destroyed, expelled, or restricted to very limited areas by state and local officials. The Native American wars and displacement in Virginia were conducted by state and local officials. The US Congress never ratified any treaties with Virginia-based tribal groups, and no reservations were created within the state through any Federal process.

When Virginia's colonial leaders made decisions about where Native Americans could live within the state, the closest thing to a national government at that time was a committee of officials in London who had been appointed by the king to oversee the colonies. Whenever Virginia officials revised/ignored various promises and approved the sale of lands that were supposed to be preserved for Native American occupation, the tribes could not invoke any Federal treaties to obtain oversight or protection by the national government.

The Pamunkey Reservation, first created in 1646, was divided between two tribal groups in 1894. The Mattaponi tribal reservation is located on the Mattaponi River, while the Pamunkey tribal reservation is about ten miles southwest on the Pamunkey River at Pamunkey Neck.

Most of the lands once defined as "reserved" for Native Americans has been transferred out of their control. The General Assembly gave a 5,000-acre grant in Gloucester County on the Piankatank River to the Kiskiaks (Chiskiaks) in 1649, stretching from Chapel Creek to Harper Creek. The Kiskiak lived in two towns within that tract.

The Kiskiak population diminished, and they sold off the property. By 1669, there were just 15 warriors remaining. Apparently the Kiskiaks consolidated into other tribes nearby; the unique identity of the tribe and land reserved for them disappeared by 1683. Reservations established for the Wiccocomico, Gingaskin, and Nottoway also have disappeared.4

Pamunkey Neck in King William County, site of today's reservation for the Pamunkey tribe on the Pamunkey River

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

Colonists acquired title to lands controlled by Native Americans in various ways. Unlike the English who landed at Jamestown, William Penn initially purchased lands from the original occupants. By the 1700's, that tradition in Pennsylvania was replaced with acquisitions through deceit, such as the Walking Purchase and treaties with Native American groups with only a marginal claim to lands being ceded.

Teedyuscung, who claimed to be the "King of the Delawares" and encouraged Native American opposition to the British during the French and Indian War, made clear in a 1756 speech that warfare was triggered by the land hunger of the colonists. He offered an alternative solution to displacing the tribes (emphasis added):5

English officials claimed ownership of lands in North America through the Right of Discovery, a legal concept that justified occupation without compensation. Virginia colonists gradually obtained title to nearly all Native American lands through conquest, through legally-adopted treaties with the tribes, and through a variety of extra-legal mechanisms that forced people to abandon territory used for settlements, farming, hunting, and gathering of wild foods.

For example, in the 1600's colonists who settled near Native American towns could release pigs and horses that destroyed Native American corn fields which were not protected from grazing by fences. When occupants of a Native American town left on a seasonal hunt in the Fall, nearby settlers could claim the land had been abandoned and obtain colonial land patents to establish new ownership and start planting tobacco.

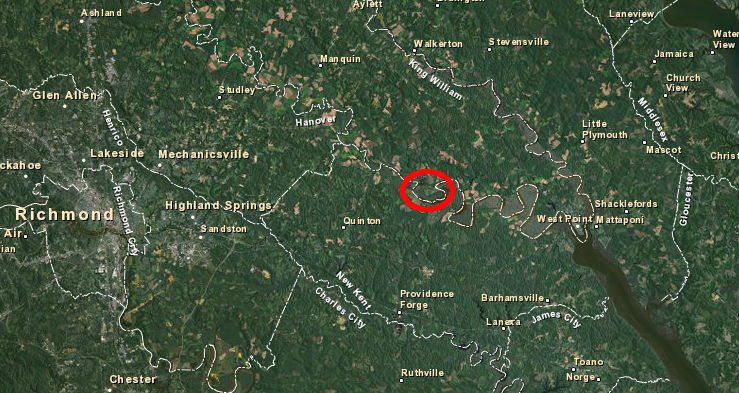

Some colonists were granted patents in anticipation of Native Americans abandoning their towns. The Portobacco group crossed the Potomac River in the 1650's to avoid the increasing number of colonists arriving in Maryland, and settled near the Rappahannock River. That Portobacco settlement survived until 1704, over 50 years since a patent had been issued to an English claimant. The owner of that patent ultimately spurred the remnants of the Portobaccos to move elsewhere, after the Virginia governor declined to protect the Native American claim to the land.6

land-hungry colonists pushed several different Native American groups, including the Rappahannocks, to Portobago in the second half of the Seventeenth Century

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

A formal reservation provided more legal protection of community land. Virginia officials have created and abolished more formal reservations than still remain. Communal reservations for the Gingaskin, Nottoway, and Wiccocomico were converted into private land.

Once a reservation was officially abolished by the Virginia General Assembly, community ownership was terminated. Land parcels that were occupied within the reservation boundaries were allocated to individuals, and that allowed non-natives to purchase the parcels from Native Americans one by one as families needed money. Such sales ultimately displaced all of the original Native American inhabitants from former reservation sites.

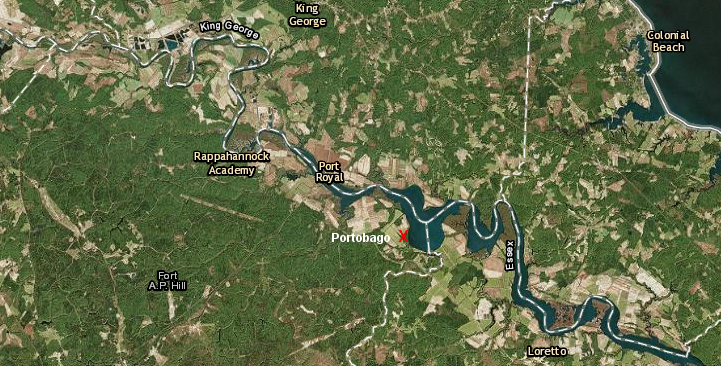

Starting in the 20th Century, some Native American tribes have acquired land to establish a base of operations for communal activities in Virginia. The Monacan were the first, when they obtained title to lands on Bear Mountain in Amherst County adjacent to the Episcopalian Mission School established in 1908 for their education.

the Monacan Tribe has re-established a base by acquiring ancestral land (red X) in the Blue Ridge mountains

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Since then, all of the tribes officially recognized by Virginia have explored the potential of creating tribally-owned land, and most have succeeded. The Nansemond acquired land from the City of Suffolk to create Mattanock Town, and the Potowmack leased 17 acres next to Duff McDuff Green Memorial Park from Stafford County to establish an educational museum and cultural village. The 10-year lease included the Duff House.7

However, there are no treaties that define those acquired properties controlled by other tribes as officially-recognized "reservations." The Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes are still the only two in Virginia to have official, state-recognized reservations.

Since ratification of the US Constitution in 1789, the Federal government has signed treaties with Native American tribes and considered them to be sovereign nations in some ways. Federal authority limits the power of state or Federal agencies to regulate activities within the boundaries of Federally-established reservations.

Most Native American reservations established by the Federal government are west of the Mississippi River. Eastern tribes were disrupted and displaced in the colonial period, forcing Native Americans westward. Cherokee, some of whom once lived in Virginia, were marched west against their will and resettled in Oklahoma.

The Federal government has also granted citizenship to Native Americans born on those reservations and assumes it has a "trust responsibility" for Federally-recognized tribes. A national commission on gambling noted the confusing status of tribal sovereignty:8

Since 1607, legal and extra-legal processes have deprived Native Americans of their land claims in Virginia. Treaties legally documented the changes in the rights of Native Americans vs. English colonists to occupy or travel through defined areas of Virginia. Several formal actions established reservations for Native American tribes to hunt, farm, and live unmolested by the newest immigrants from England.

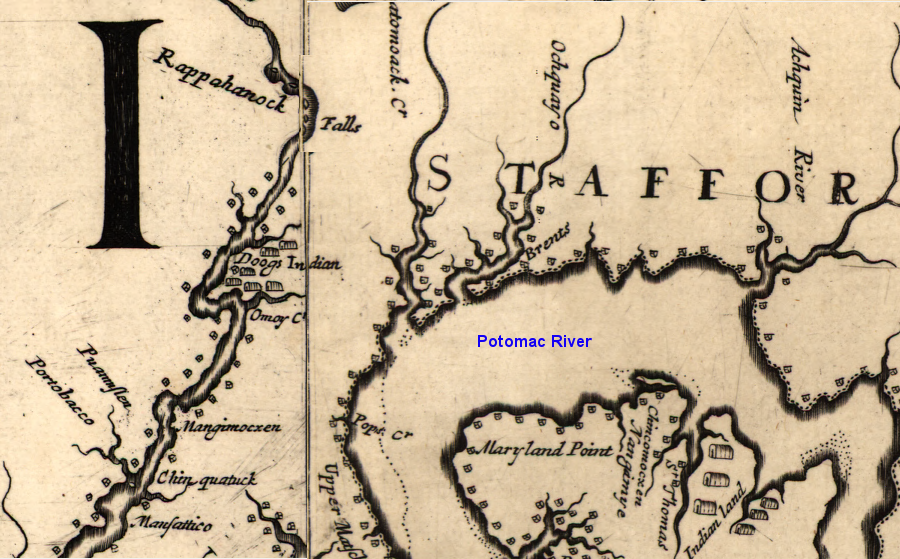

the Dogue tribe had a town on the Rappahannock River in 1670 (downstream of where Fredericksburg would be built later on the Fall Line), before any reservations were created in Virginia

(NOTE: map is oriented so north is to the right, not towards the top)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 by Augustine Herrman

There are no Federal treaties with Virginia's tribal groups; the Native American reservations in Virginia were not created by any act of the US Congress. The Federal government guaranteed no special rights for Virginia tribes when negotiating reservation boundaries, because there were no Federal negotiations during the displacement of the tribes in Virginia. Lawsuits about off-reservation rights are common in the Pacific Northwest, but Virginia tribes have no Federal guarantees for fishing rights in rivers or the Chesapeake Bay.

The official status of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi reservations was formalized by the Treaty of Middle Plantation in 1677 when Native Americans signed a deal with the colony of Virginia, long before the creation of the United States. The Federal government finally granted Federal recognition to the Pamunkey Tribe in 2015 and provided access to special programs offered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but that did not change the status of the state-established reservation. The Supreme Court of the United States ruled in 2006:9

Source: PBS Origins, Native American Reservations, Explained

State recognition and formal creation of a reservation does not grant a Virginia tribe exclusive police jurisdiction over the lands within that reservation. The Attorney General of Virginia has declared that the state of Virginia owns the lands in fee on which the Pamunkey and Mattaponi reservations are located.

The tribes have exclusive use, but can not sell the land without state approval. The Attorney General also ruled that the King William County sheriff's office:10

Formal recognition by the state does not guarantee that government officials will defer to Native American claims of special cultural rights on lands outside a reservation. Virginia courts ruled against a Mattaponi claim that the 1677 treaty should block consideration of a dam and reservoir proposed by Newport News on Cohoke Creek. The Mattaponi claimed that the cultural impacts of the proposed King William Reservoir were excessive, but state courts refused to rule that the 1677 treaty could be used to stop construction of the reservoir.11

The Corps of Engineers ultimately refused to issue the necessary "Section 404" wetlands permit for the King William Reservoir project. The Federal agency ruled that Newport News had failed to demonstrate a large enough public need for the water. The demonstrated need was not sufficiently large to justify the environmental impacts.

Federal recognition of the Pamunkey in 2015 created the possibility that the Bureau of Indian Affairs could take the entire reservation into trust. Federal trust status would provide more protection against dissolution of the reservation, but the Pamunkey's primary interest at the time was in expanding the reservation to include a parcel in Norfolk.

The tribe's plans for a casino on the Elizabeth River waterfront at Harbor Park would have been enhanced. Under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act passed in 1988, if the Pamunkey got that land added to their reservation and placed within Federal trust responsibility, then a casino could offer Class III gaming with slot machines and roulette wheels.12

In the end, the Pamunkey obtained a state license and local approval to build and operate a casino in Norfolk without having to involve the Federal government or expand the reservation, and without having to contend with objections to their land claims from the Nansemond tribe.

In 2022, the General Assembly created the Virginia Black, Indigenous, and People of Color Historic Preservation Fund. It was designed to help purchase culturally historic sites for communities of color. For Native Americans, the fund was planned to facilitate acquiring sites of cultural significance. Those included the Monacan town of Rassawek in Fluvanna County, and the Patawomeck Tribe's main town site at Crows Nest in Stafford County.13

Starting in 2018, multiple land acquisitions along the Rappahannock River expanded the ownership of the Rappahannock tribe at Fones Cliff. Starting in 2019, the Chickahominy tribe began acquiring parcels on the James and Chickahominy rivers. In 2023, the Mattaponi acquired 866 acres along the Mattaponi river. These lands were tribally-owned, but technically not "reservations." The property had been acquired by colonists in the 1600's, not reserved from ever being sold like the Mattaponi and Pamunkey reservations.14

Between 2019-2025, Stafford County leased Duff Green Park to the Patawomeck tribe. In 2025, The Nature Conservancy transferred 870 acres to the tribe. That land base was not a "reservation" and a Virginia Outdoors Foundation conservation easement limited some land use options, but the tribe had finally regained ownership of a substantial territory again.15

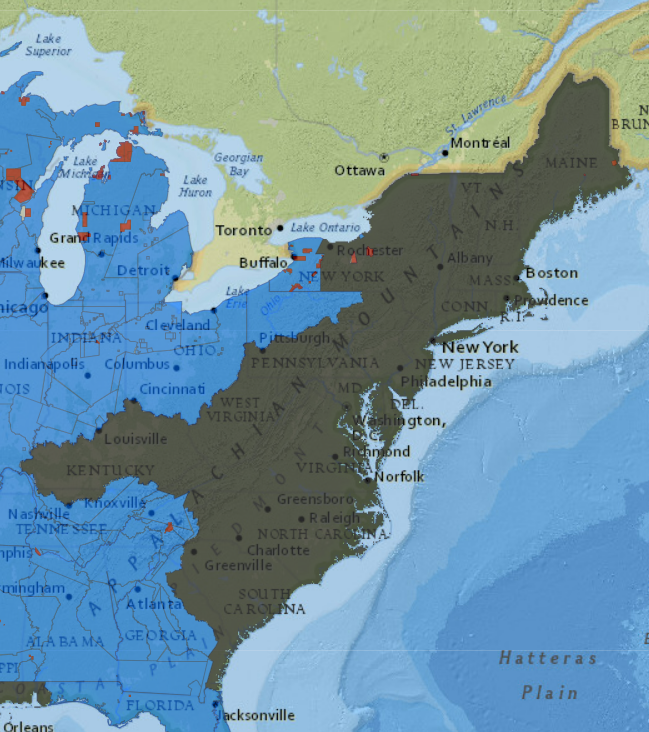

by 1776, Native Americans had been displaced from much of the eastern seaboard (gray area)

Source: Claudio Saunt, invasion of America

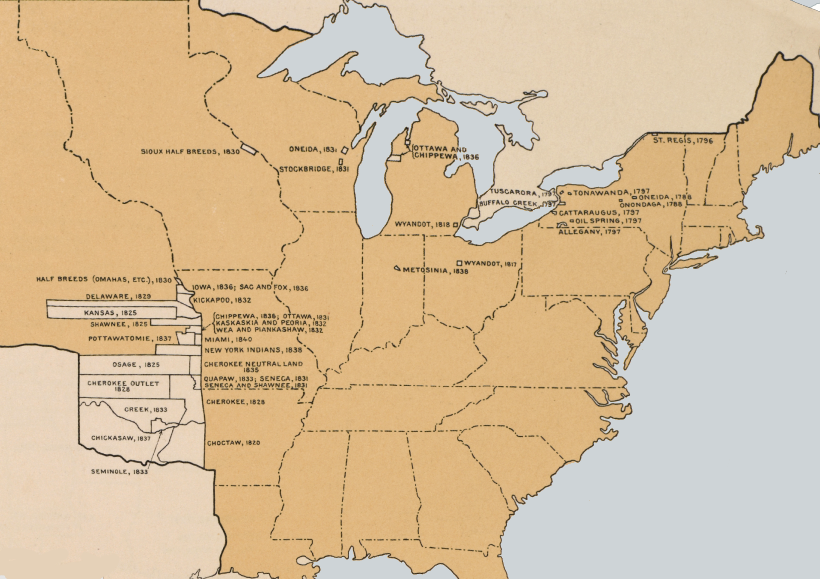

fifty years after the creation of the United States, the Cherokee and most other tribes had been forced to move west of the Mississippi River - and there were no Native American reservations in the southeastern states

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Indian Reservations, 1840 (Plate 35a, digitized by University of Richmond)

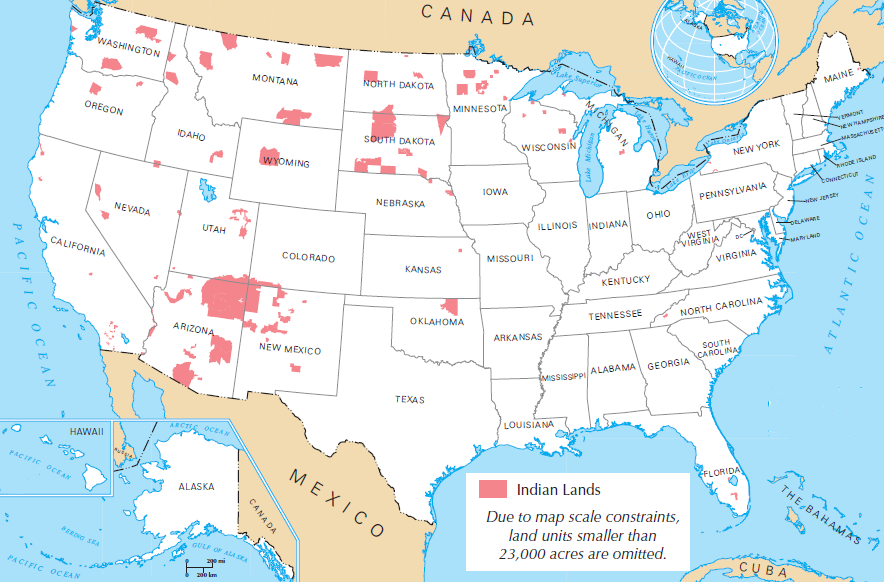

large Federally-established reservations portrayed on this map show how Native Americans were displaced from the eastern portion of the United States

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Reference and Outline Maps of the United States - Indian Lands