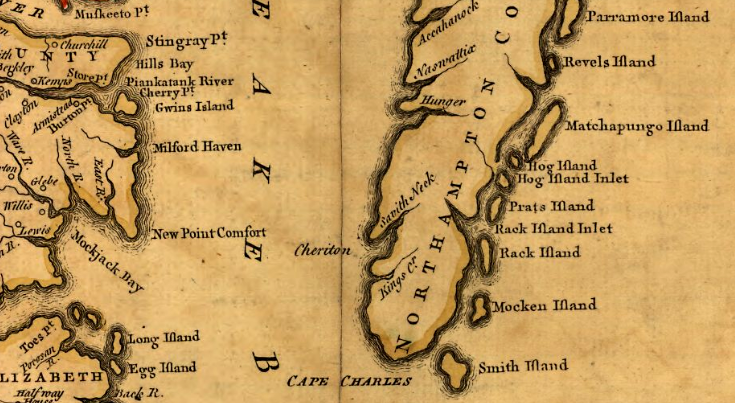

John Smith recorded the location of "kings houses" for the Accomacs and Occohannocks

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith

John Smith recorded the location of "kings houses" for the Accomacs and Occohannocks

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith

The Accomac tribe occupied the southern part of the Eastern Shore, in what is now Northampton County, when the English arrived in 1607. The Occohannocks lived further north, in what is now Accomac County. The leader of the Accomacs, Esmy Shichan, appointed his brother Kiptopeke to rule as weroance over the Occohannocks.1

Powhatan's warriors had crossed the Chesapeake Bay in canoes, and they were part of his paramount chiefdom. His control over the Accomac was not as complete as his control over tribes within the core of Tsenacommacah; the Eastern Shore was on the "ethnic fringe."2

The arrival of the English gave the Accomacs more freedom, and traditionally tribe was viewed as friendly to the colonists. When Powhatan sought to isolate and weaken the English by banning any of his subordinates from providing corn, the Accomacs did not comply.

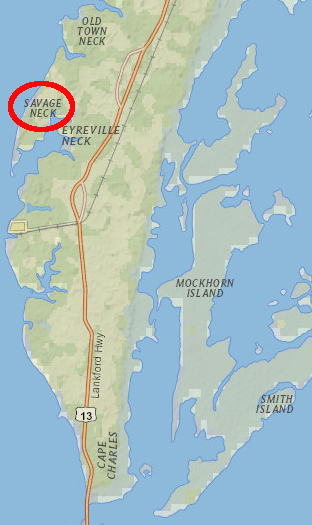

In the early 1620's, the Accomac chief (known to the English as "Laughing King" because he was so friendly) willingly gave a large tract to Thomas Savage. Part of those 9,000 acres are still known as Savage Neck, named after an English immigrant rather than after the Native Americans.

Savage Neck in Northampton County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Savage had emigrated to Virginia in 1608, and John Smith sent him to live with Powhatan in 1609. He fled Werowocomoco to shelter among the Patawomeck, and became a valued interpreter for both English and Algonquian-speaking tribes seeking to trade with each other. Savage became friends with the Occohannocks and Accomacs on the Eastern Shore when he assisted in trading expeditions starting in 1621.3

The Accomac "Laughing King" allowed the Virginia Company to occupy lands on the Eastern Shore, including a salt-making operation. In 1621, the Accomacs refused to assist Opechancanough in his plans for a violent uprising against the colonists. Opechancanough was unable to convince them to supply a poison that could be made from the water hemlock plant, which was abundant on the Eastern Shore.4

The Accomacs were allowed to sell lands to the English without special approval from the General Assembly. To protect the core of the Accomac territory and maintain the capacity of the tribe to supply furs and food to the English, the colony established a 1,500-acre Gingaskin reservation in Northampton County in 1640. By that time, the Accomacs were called the Gingaskins.

The tribe used the county courts to sue Englishmen who were occupying lands that were supposedly reserved, but encroachment by colonists was so successful that a 650-acre tract finally was surveyed to mark the boundaries of the remainder of the reservation. A patent for that land was issued in 1680, formalizing ownership according to English law.

In 1792, the General Assembly mandated that the Northampton County court appoint trustees to manage the reservation and to deal with disputes over land leased to local farmers. The trustees were white men, able to testify in the courts.

When they performed their duty, the trustees could limit the ability of land-hungry colonists to ignore the boundaries and start using Gingaskin territory without legal authority. Trustees could also limit the ability of Gingaskins, especially weroances, to sell community-owned land. However, tribal identity and population diminished to the point that no Gingaskin weroances or council members are documented after the 1660's.5

by 1751, the presence of the Gingaskin was not significant enough to be recorded on the map by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1751)

The willingness of the General Assembly to help the tribe hold onto their land changed by the 1800's. The Native Americans had intermarried with free blacks rather than colonists. The whites on the Eastern Shore considered the Gingaskins to be more "mulatto" (mixed race) than "Indian." The men continued their Native American pattern of hunting and fishing, while their tax-exempt reservation lands were leased to local farmers.

Local whites feared that the reservation was becoming a reservoir of free blacks that posed a threat to the white community. As Native Americans, the Gingaskins were able to carry guns on their reservation. Slaves and free blacks in the community were not allowed to be armed.6

Just before the start of the War of 1812, a rumor of a slave revolt frightened whites on the Eastern Shore. That region was isolated by the Chesapeake Bay, and if a slave uprising occurred the whites would have a hard time getting reinforcements.

After one of the Gingaskins was convicted of subversive behavior, the reservation's trustees tried to convince the Native Americans to terminate their protected (and tax-exempt) status and be classified as "free negroes." The Gingaskins did manage to block proposals to sell the entire reservation and give money to each member of the tribe, but:8

In the end, the trustees petitioned the General Assembly for allotment of reservation lands to individual owners, and allowing the individual owners to sell whenever they wished. The legislature quickly authorized distribution of community-owned lands at the Gingaskin Reservation in 1813.7

Each of the 27 remaining adults on the reservation received about 25 acres, with the right to sell that land. The Gingaskins were in no hurry to sell and leave, however. Only 1/3 of the total land was sold in the next 15 years, and 3/4 of the Gingaskin who received allotments of land held onto their property, before the Nat Turner insurrection in 1831.

That uprising in Southampton County frightened whites on the Eastern Shore, and a surge of land purchases by whites displaced many of the Gingaskins. Many continued to live in the area, but the once-compact community centered on the reservation lands was broken up after 1831.9

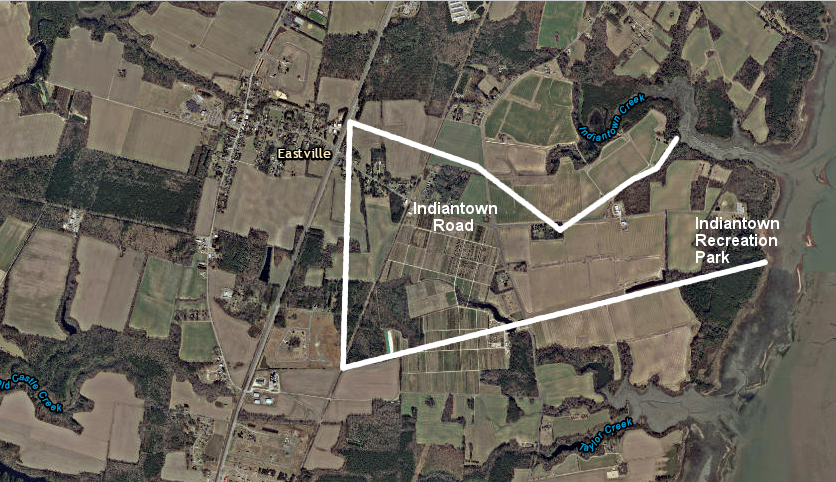

Today, the former reservation consists of farmed fields, patches of woodlands, and the Indiantown Recreation Park.10

from Eastville to the Indiantown Recreation Park, Indiantown Road cuts through the center of the former Gingaskin Reservation

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online