- Sources of Northern Virginia Drinking Water

- What is the source for your home?

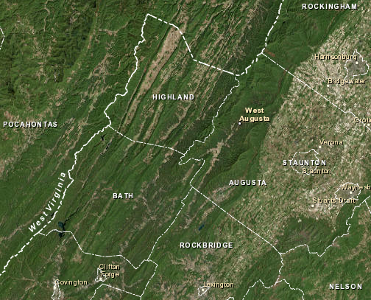

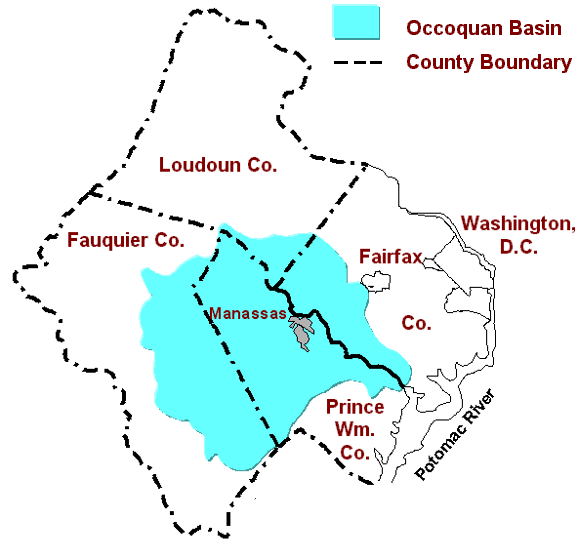

- The Occoquan Watershed

- The Occoquan Reservoir was built in 1950's by a private for-profit corporation to supply drinking water to Alexandria, replacing Lake Barcroft as the city's primary source.

- The County of Fairfax acquired the private reservoir through condemnation. The private utility did not want to sell its profit-making operation, which had great potential for future growth. However, Fairfax County wanted to control its water rates in order to attract business and keep voters happy with low-cost, high-quality water. (The seizure of Alexandria's water supply may also have been a hardball negotiating tactic, used to block plans by the city to annex more land from Fairfax County.)

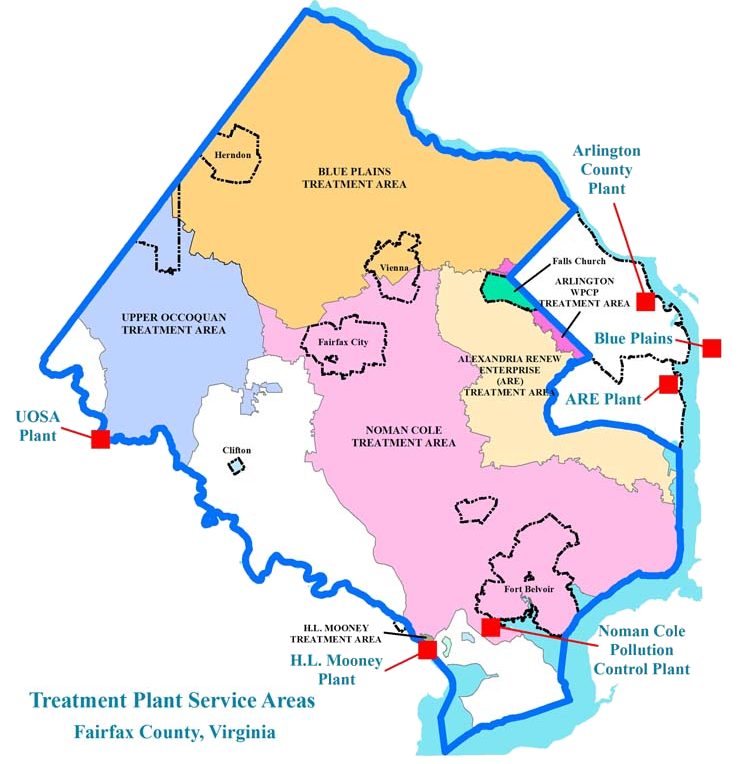

- The Occoquan Reservoir is the primary source of drinking water for about half of Fairfax Water customers. The City of Alexandria and eastern Prince William County (Dale City) are still serviced by private, for-profit utility companies that buy water at wholesale rates from Fairfax Water, and resell to customers at retail cost.

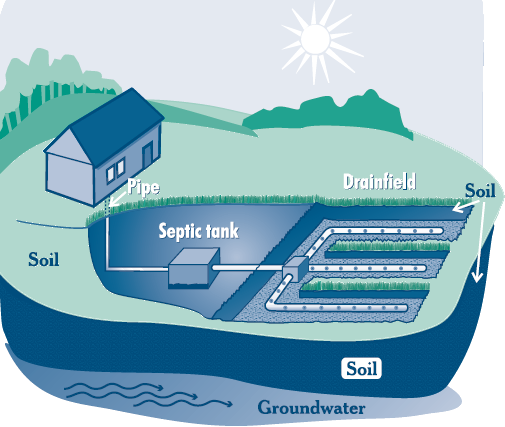

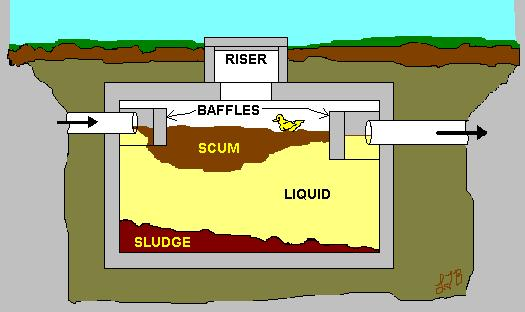

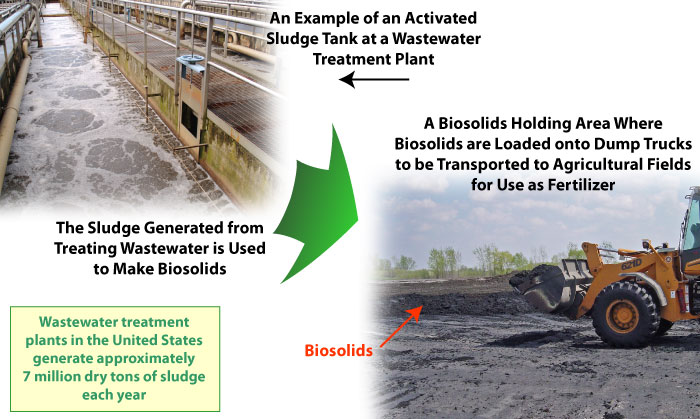

- As Fairfax County developed in 1960's, the Occoquan Reservoir was heavily polluted by human sewage. Small "package" sewage treatment plants built for new subdivisions killed bacteria in human waste from all the new houses, but those facilities did not remove nutrients (especially nitrogen and phosphorous) from wastewater. Fertilizers on suburban yards also washed downstream into the reservoir.

- By the early 1970's, Occoquan Reservoir was organic soup. Blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) covered the surface, and the stench that made clear something had to be done.

- Alternatives included 1) block construction of new housing units in the Occoquan watershed, 2) pipe all wastewater to sewage plants outside of the watershed, or 3) upgrade the sewage treatment processing plants in the watershed.

- The ultimate solution was to replace the existing sewage treatment systems. The regional Upper Occoquan Sewage Authority (UOSA) built a state-of-the-art facilty to replace all of the old sewage plants (NOTE: the Occoquan Forest plant on Davis Ford Road in Prince William will be the last to close, soon...).

- Since 1978, UOSA plant on Bull Run near Centreville has processed sewage so completely, you could drink the effluent that emerges at the discharge site. Yes, the sewage plant prodict is drinking water quality.

- Many people do drink the UOSA sewage discharge - at times, including people using water fountains on the Fairfax campus of GMU.

- No, don't have a direct toilet-to-tap connection. The UOSA effluent flows 12 miles down Bull Run to the Occoquan Reservoir first, before reaching the intake for Fairfax Water's Griffith Water Treatment Plant at Lorton. Whatever is shoved down garbage disposals, discharged from showers, and flushed down toilets in Centreville and Manassas goes through UOSA in Centrevile, then 12 miles later becomes the drinking water for half of Fairfax Water customers (as well as City of Alexandria and eastern Prince William).

- Wastewater discharged from UOSA facility is cleaner than water in Bull Run itself. It would be cost-effective to pipe water directly from sewage plant to Fairfax Water drinking water treatment plant at Occoquan. However, customers might object to a direct toilet-to-tap system. That is why clean water is dumped into Bull Run, that clean water gets dirty as it moves downstream, then the water from the Occoquan Reservoir is cleaned again at the Griffith Water Treatement Plant in Lorton. (Hey, how does that sewage taste?)

Occoquan Reservoir receives wastewater from Fauquier, Prince William, and Fairfax counties, plus the cities of Manassas and Manassas Park

Source: Northern Virginia Regional Commission