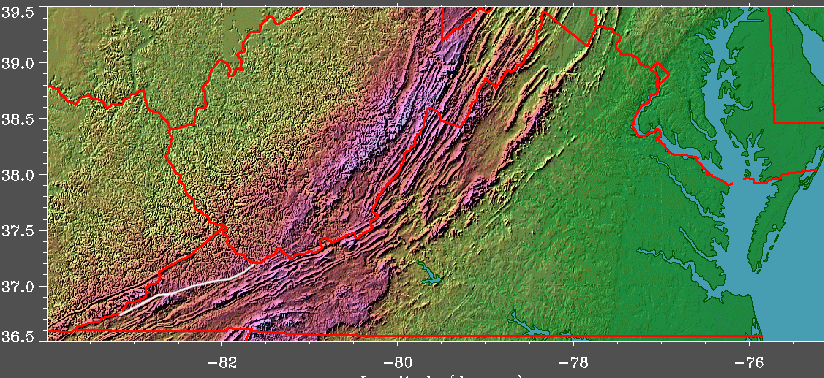

Virginia is bumpy in the west, flat in the east

Source: Ray Sterner, Color Landform Atlas of the United States

(with the tilted rocks of the Triassic Basin in the background)

1) Let's refresh our understanding of the charters and boundaries first - see Boundaries and Charters of Virginia. Geo-leaning is cumulative, and many pieces are connected. Few of the investors who financed the project to colonize Virginia chose to "venture" their lives, so why did they want the boundaries extended?) The semester has many weeks ahead, and we'll get to the edges of Virginia with North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia soon.

2) Now let's start at a very basic level: examine Ray Sterner's Relief Map of Virginia.

Virginia is bumpy in the west, flat in the east

Source: Ray Sterner, Color Landform Atlas of the United States

3) The challenge of describing the geology is a lot easier than the challenge of explaining why we see mountains only in the western part of the state. Get comfortable with using different types of maps and recognizing how they differ.

Some maps show topography via contour lines or the cartographic technique of shading the mountains. Others, such as road maps, may help you find a place - but if you don't have a "layer" of topography, you might miss the geologic context. To understand how Virginia has been shaped over time, we will "dig deeper" this week.

topographic maps display elevation changes using contour lines

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Warm Springs, VA 7.5-minute topographical map (2016)

Let's start with:

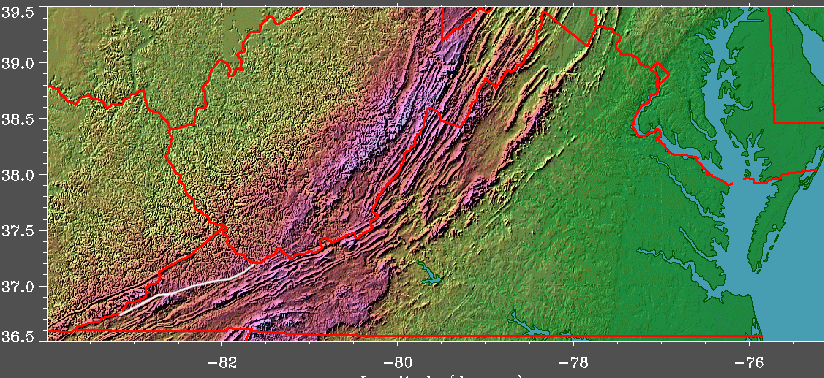

within the Piedmont are Triassic Basins, created as Africa and North America began to split apart 250 million years ago

Source: James Madison University, A Description of the Geology of Virginia

different geologic regions of Virginia can be defined by the different ages of the bedrock, and/or the different types of bedrock

Source: James Madison University, A Description of the Geology of Virginia

|

Now let's examine the rocks themselves, and how the edge of the North American tectonic plate grew over time to form Virginia. The five physiographic regions each have their own story, but those stories are inter-related:

|

|

Now watch the video, Making Virginia, Chunk By Chunk, Through Plate Tectonics. It is a 16-minute summary of a billion years of landscape evolution. The video is on GMU's Blackboard site for this class. Please follow the link to the video in the Week 2 folder.

Quick Review: The Piedmont is a complex assemblage of rocks. Many chunks of rock were created somewhere else initially, then transported to their current location by tectonic forces. There are faults which identify where different "terranes" were pushed up against each other. Three times, between 450 million-300 million years ago, those mysterious tectonic forces made Virginia larger, by adding chunks to what is now the eastern edge of the North American continent. Each addition involved compressing the bedrock and metamorphosing old formations, plus lifting up mountain ranges in three orogenies. 300 million years of erosion has removed each of those mountain ranges, but their roots are still visible in places like the quarries at the Fall Line in Occoquan, Richmond, and Petersburg.

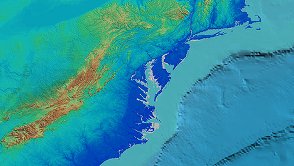

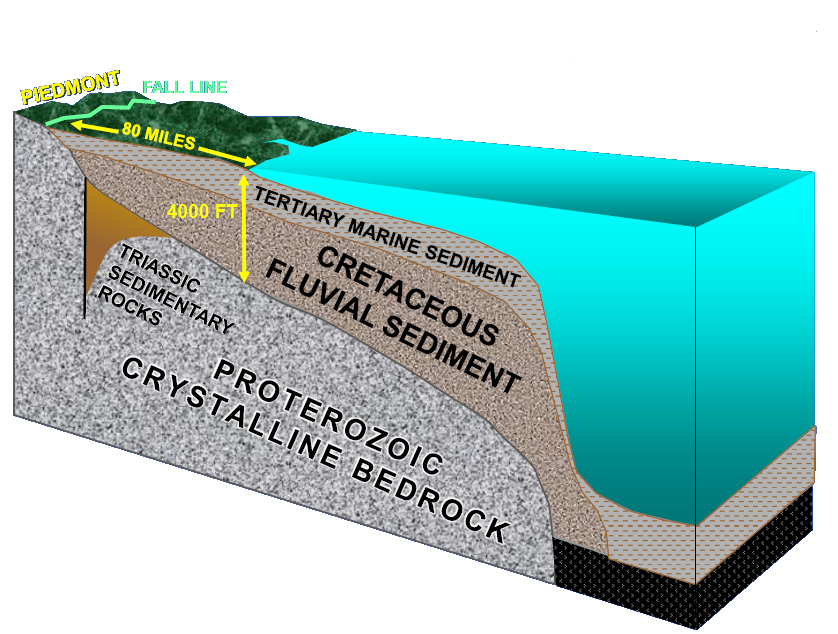

The crystalized hard bedrock underneath the Piedmont extends east to the Chesapeake Bay and further east, to the far eastern edge of the Continental Shelf. That basement, the crystalized hard bedrock, is buried underneath the sediments of the Coastal Plain *and* the waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

the Coastal Plain is composed of layers of sediments deposited on top of the basement bedrock, the "terranes" accreted onto the edge of the continent and the Grenville-age core of North America

Source: Randy McBride, US Geological Survey, The Potomac Aquifer of the Virginia Coastal Plain

The sediments of the Coastal Plain and the Continental Shelf are the eroded remnants of the mountain ranges that once towered 20,000' high in Virginia. Those sediments sit on top of the Greenville-age basement bedrock.

Quarries west of the Fall Line could be excavating metamorphic rocks smushed up against Virginia as different terranes were emplaced, but the quarries in the Triassic Basins will be excavating igbneoys diabase. That is the lava that rose to the surface when Pangea split up, when Africa and North America moved apart.

One of the cracks that formed in the earth's crust during the break-up of Pangea is still active. For 200 million years, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge has been oozing basalt and widening the Atlantic Ocean, but the igneous rocks quarried in the Triassic Basins of Virginia have been cooling for 150 million years.

Question: Why are the Appalachian Plateau rock layers not broken and folded?

Once you have fired the synapses in your brain and determined the correct answer, compare with this assessment.

If you dig all the way through the Coastal Plain and through the center of the earth... you won't pop out on the other side in China. The antipode for Virginia is in the Indian Ocean west of Australia. The area searched for the missing Malaysian jetliner in 2014 was roughly the location of the opposite side of the globe from Virginia.

NOTE: Urban revitalization in Anacostia may result in new skyscrapers, even if the depth to bedrock is greater than in downtown DC, because the marginal costs of excavation are minor compared to other expenses. The classic description of why Manhattan in New York City has a gap between the tall buildings in lower Manhattan (where the World Trade Center was built) and at midtown Manhattan (where the Empire State Building was built) may be just an urban myth. The standard explanation is that developers built only relatively-small buildings in the gap because bedrock is buried deeper between those two locations. However, a 2009 study concluded that "bedrock had, at most, a small effect on the formation of the skyline" of Manhattan.1

So much for what I learned in my geography classes - and don't assume all the material posted on VirginiaPlaces is correct, either. Use your critical thinking skills; think for yourself... and contact me at cgrymes [at] gmu.edu when you have questions.

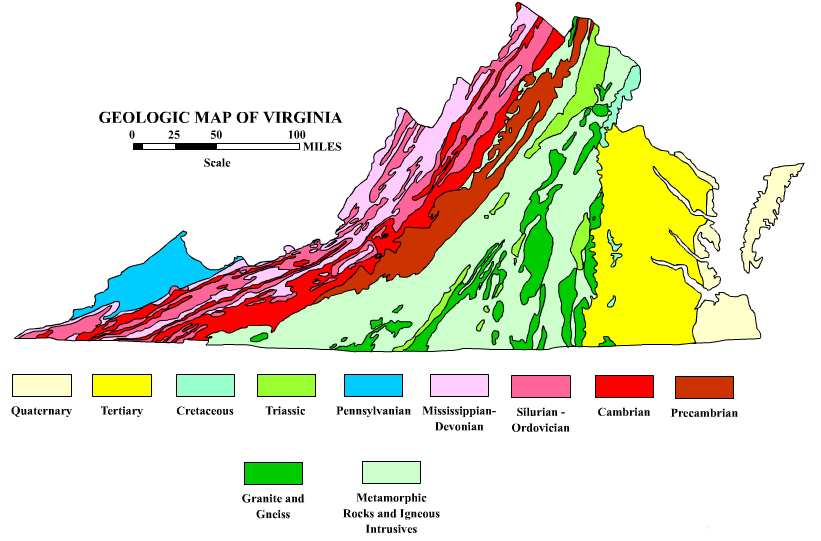

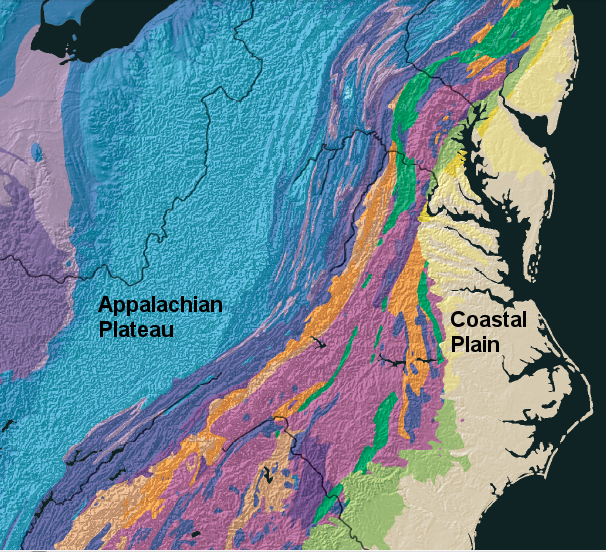

Virginia bedrock is not uniform; various formations are exposed at the surface between the Coastal Plain on the East and the Appalachian Plateau in West Virginia

Source: USGS Geologic Investigations Series I-2781, The North America Tapestry of Time and Terrain

Whew! Now that you have rocks in your head, you can understand how physical geography is so fundamental to the cultural geography of Virginia. Read a series of short "overview" pages on:

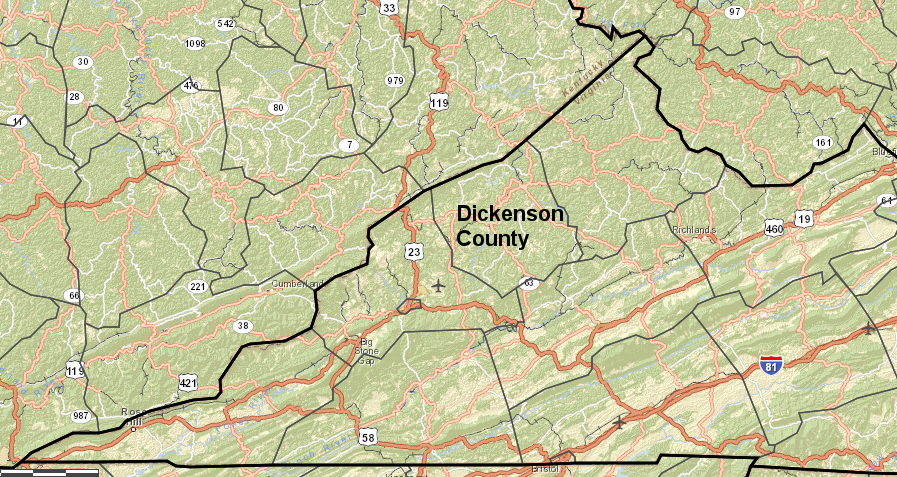

4) Spotlight on... Dickenson County (in the heart of Virginia's coal country)

what is the best way for Southwestern Virginia, far from interstate highways and population centers, to attract jobs in the new economy?

Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership, Virginia's e-Region

5) Watch the Virginia Journey video: The Stones Beneath Your Feet on GMU-TV streaming video

6) Web Exercise:

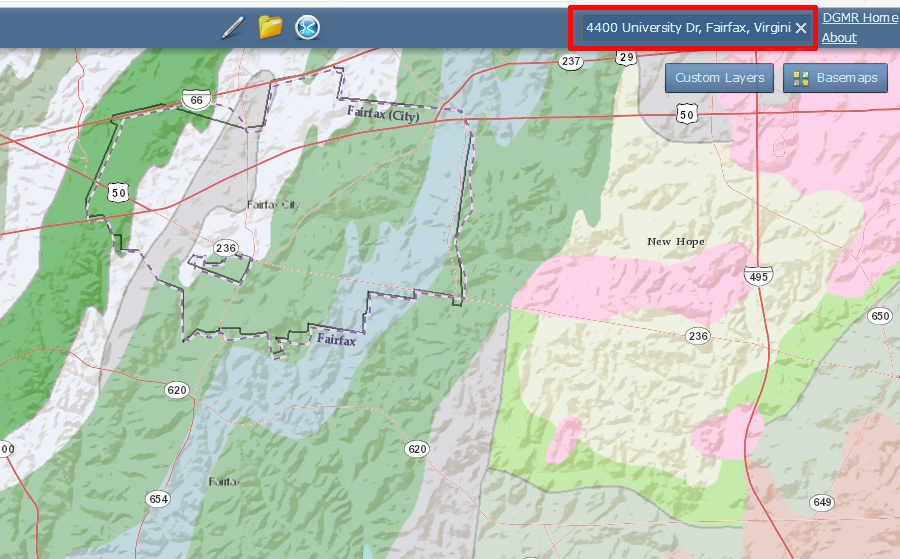

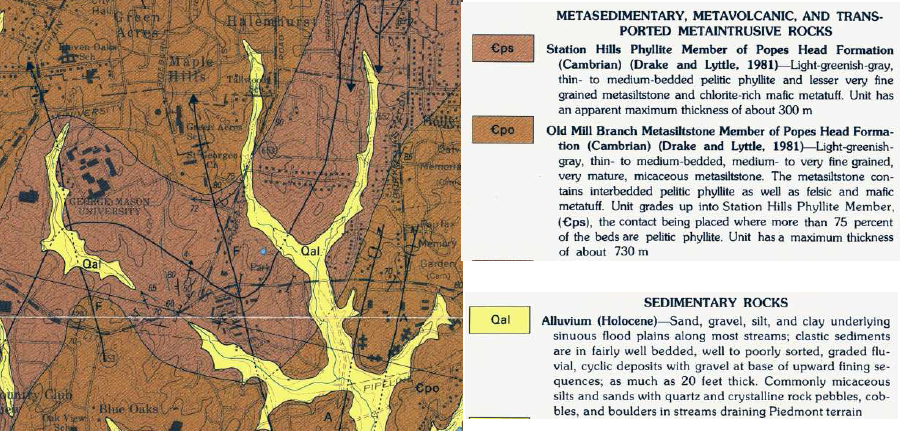

Visit the Interactive Geologic Map, hosted by the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy. Type in the GMU Fairfax address to explore the patterns of bedrock near the campus.

We are in the Piedmont physiographic province, between the Blue Ridge on the west and the Coastal Plain on the east. The rocks underneath the campus were once offshore, part of the ocean bottom or island arcs similar to Japan.

The rocks underneath Fenwick Library and the Johnson Center were smushed ("accreted," if you like big words) onto the edge of Laurentia, then re-smushed again during the Taconic, Acadian, and Appalachian orogenies. The original rocks recrystalized under the heat and pressure during the mountain-building events, so they would be characterized today as metamorphic rather than sedimentary. If any of the rocks actually melted before recrystalizing, then those would be igneous.

identify the bedrock under GMU's Farfax campus

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Interactive Geologic Map

7) Complete the Map Exercise using the Virginia Atlas and Gazetteer:

|

|

Trace I-95 and I-64 across the state, making a "transect" from east to west and north to south:

Did you notice some places were on more than one transportation corridor? What do you think was built first, the roads or the cities? To what extent do roads determine where we live in Virginia, and to what extent do residences/employment centers determine where we build roads?

8) Complete the Site Visit and submit your first Site Report:

Find a road cut, construction project - or make your own hole in the ground in your back yard - and note the characteristics of the bedrock or deepest layer of soil you can see exposed. Is it predominantly pale sand, orange clay, purple sandstone, black basalt, greenstone, gray limestone? What physiographic province are you in?

In what physiographic province is your site located? How old is the bedrock beneath your feet? Take pictures of your site, note the topography, look for excavations and outcrops that expose the bedrock, and think through why your site is dominated by crystalline metamorphic rocks, red Triassic sandstones, loose sand and gravel, or whatever...

Use the Geographic Names Information System or a topographic map to identify the elevation at your site. How has the local topgraphy affected development there? Were the earliest dirt roads located on ridges where they would dry out faster after a rain, or in valleys along the creeks so people could avoid going up/down the steep sides of hills? Are recently-constructed houses placed on bedrock, or do builders create an artificial foundation to provide a stable platform for the structure? When utilities are buried or roads re-aligned, is blasting necessary to removed rock outcrops or can a bulldozer simply push the soil around?

How is the soil? Historically, was your area preferred by farmers or avoided? Typically, good soils were farmed for crops like tobacco and grains (corn, wheat, barley), hilly areas were used for orchards or grazing land for cattle/sheep/horses. The least-productive soils were left in forest to grow wood for fuel, fences, and other building material - how do you think your site was treated by the farmers during Virginia's colonial period?

How intact is the topsoil at your site? Do you see grass and weeds growing well in areas without fertilization, or was your topsoil disturbed by construction and mixed with nutrient-poor subsoil so today it's a challenge to grow a decent garden without people having to add organic material (compost, peat moss, etc.)?

Submit a 1-page (single-space) report via Blackboard (look at the Assignments tab) on the geology of your chosen site as your Field Trip report, and start building your Neighborhood Portfolio for the end of the semester. You can see the beginnings of such a portfolio, which might be a guide for what you plan to produce, for a specific location: West End Richmond.

Some resources of potential value to examine your site in detail:

9) Read two blog posts:

- Should Manassas Park... Disappear?

- Burning Waste Coal to Restore the Land (from James Bacon's blog, Bacon's Rebellion)

Throughout the semester, blog posts will address facets of Virginia geography that are in the news. The topics may or may not match the focus of the content being covered for the particular week, but the material will be relevant to what we will study during the semester.